The World of the Renaissance Herbal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

English Roots

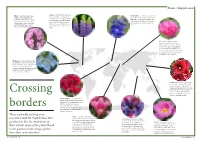

Plants / English roots Lupin – cultivated for thousands of Phlox – arrived in Europe from Delphinium – modern day varieties are years, originally as a fodder plant, Virginia, North America in the the result of interbreeding of species from as far apart as ancient Egypt and the early 18th century before crossing many parts of the world, from the Swiss Peruvian Andes. The tall colourful the channel a century later. Many Alps to Siberia. They have been a part of spires popular in English gardens varieties have been bred since not the English garden since at least Tudor have their origin in North American only in England but also in the times. species that arrived in Britain in the Netherlands and United States. 1820s. Rose – the English rose is the result of centuries of breeding of many varieties of rose from around world. One of these is the Damask rose, named after the Syrian city of Damascus, famous for its fragrance. It is thought to have first been brought to England by the Crusaders. Hydrangea – first introduced from Pennsylvania, North America in 1736. In the nineteenth century they became a favourite of plant hunters and botanists, including the famous Joseph Banks who brought more varieties back from China and Japan. Hollyhock – possible origins range from and Syria to India but mostly likely to be natives of China. This statuesque plant worked its way along the Silk Road over many centuries and is first mentioned in English Crossing literature in John Gardiners poem ’Feate of Gardenini’ in 1440. Sweet William – first appeared in English botanist John Gerard’s garden catalogue in 1596 having made their way from mountainous regions of southern Europe, such as the borders Pyrenees and the Carpathians. -

Invented Herbal Tradition.Pdf

Journal of Ethnopharmacology 247 (2020) 112254 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Ethnopharmacology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jethpharm Inventing a herbal tradition: The complex roots of the current popularity of T Epilobium angustifolium in Eastern Europe Renata Sõukanda, Giulia Mattaliaa, Valeria Kolosovaa,b, Nataliya Stryametsa, Julia Prakofjewaa, Olga Belichenkoa, Natalia Kuznetsovaa,b, Sabrina Minuzzia, Liisi Keedusc, Baiba Prūsed, ∗ Andra Simanovad, Aleksandra Ippolitovae, Raivo Kallef,g, a Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, Via Torino 155, 30172, Mestre, Venice, Italy b Institute for Linguistic Studies, Russian Academy of Sciences, Tuchkov pereulok 9, 199004, St Petersburg, Russia c Tallinn University, Narva rd 25, 10120, Tallinn, Estonia d Institute for Environmental Solutions, "Lidlauks”, Priekuļu parish, LV-4126, Priekuļu county, Latvia e A.M. Gorky Institute of World Literature of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 25a Povarskaya st, 121069, Moscow, Russia f Kuldvillane OÜ, Umbusi village, Põltsamaa parish, Jõgeva county, 48026, Estonia g University of Gastronomic Sciences, Piazza Vittorio Emanuele 9, 12042, Pollenzo, Bra, Cn, Italy ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Ethnopharmacological relevance: Currently various scientific and popular sources provide a wide spectrum of Epilobium angustifolium ethnopharmacological information on many plants, yet the sources of that information, as well as the in- Ancient herbals formation itself, are often not clear, potentially resulting in the erroneous use of plants among lay people or even Eastern Europe in official medicine. Our field studies in seven countries on the Eastern edge of Europe have revealed anunusual source interpretation increase in the medicinal use of Epilobium angustifolium L., especially in Estonia, where the majority of uses were Ethnopharmacology specifically related to “men's problems”. -

A Biographical Index of British and Irish Botanists

L Biographical Index of British and Irish Botanists. TTTEN & BOULGER, A BIOaEAPHICAL INDEX OF BKITISH AND IRISH BOTANISTS. BIOGRAPHICAL INDEX OF BRITISH AND IRISH BOTANISTS COMPILED BY JAMES BEITTEN, F.L.S. SENIOR ASSISTANT, DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY, BBITISH MUSEUM AKD G. S. BOULGEE, E.L. S., F. G. S. PROFESSOR OF BOTANY, CITY OF LONDON COLLEGE LONDON WEST, NEWMAN & CO 54 HATTON GARDEN 1893 LONDON PRINTED BY WEST, NEWMAN AND HATTON GAEDEN PEEFACE. A FEW words of explanation as to the object and scope of this Index may fitly appear as an introduction to the work. It is intended mainly as a guide to further information, and not as a bibliography or biography. We have been liberal in including all who have in any way contributed to the literature of Botany, who have made scientific collections of plants, or have otherwise assisted directly in the progress of Botany, exclusive of pure Horticulture. We have not, as a rule, included those who were merely patrons of workers, or those known only as contributing small details to a local Flora. Where known, the name is followed by the years of birth and death, which, when uncertain, are marked with a ? or c. [circa) ; or merely approximate dates of "flourishing" are given. Then follows the place and day of bu'th and death, and the place of burial ; a brief indication of social position or occupation, espe- cially in the cases of artisan botanists and of professional collectors; chief university degrees, or other titles or offices held, and dates of election to the Linnean and Eoyal Societies. -

364 Journal of the History of Medicine : July 1974 He Wrote of the Mistrust Which Certain Pathologists Had of the Accuracy and Fidelity of the Microscope

364 Journal of the History of Medicine : July 1974 he wrote of the mistrust which certain pathologists had of the accuracy and fidelity of the microscope. Yet he was not free from fallibility and human error. He left the mechanism of growth in cancer without a strong theoretical state- ment, a sad neglect to this day. No matter. Ober's book fulfills numerous educational needs for any student of disease. He is to be congratulated and encouraged to further his efforts. Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jhmas/article/XXIX/3/364/797140 by guest on 01 October 2021 WOLFGANG-HAGEN HEIN. iUustrierter Apotheker-Kalauler 1974. Stuttgart, Deutscher Apodieker, 1974. 36 pp., illus. DM11,50. Reviewed by ALBERT W. FRENKEL, Professor, Department of Botany, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, Minnesota 55101. This calendar in its thirty-third year represents a most valuable and informa- tive collection of selected events in the history of Pharmacy during the past five centuries. Thirty-six black and white Central European artistic expressions are represented, ranging as far back as 1497 with die wood-cut of Apotheker- Laboratorium from the 'Chirurgiebuch' of Hieronymus Brunschwig (plate 30) to modern art forms. The latter are represented by a reproduction of the doors of the new addition to die 'Markt-Apotheke' in Neunkirchen am Brand, de- signed by the sculptor Felix Miiller, and plates produced by Karl DSrfuss (1972): depicting the healing power of plant substances; the offering of natural and synthetic curative substances to the sick by Pharmacy; and die power of plants to utilize sunlight and minerals in the synthesis of food and of healing substances. -

The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a Reconstruction of the Clusius Garden

The Netherlandish humanist Carolus Clusius (Arras 1526- Leiden 1609) is one of the most important European the exotic botanists of the sixteenth century. He is the author of innovative, internationally famous botanical publications, the exotic worldof he introduced exotic plants such as the tulip and potato world of in the Low Countries, and he was advisor of princes and aristocrats in various European countries, professor and director of the Hortus botanicus in Leiden, and central figure in a vast European network of exchanges. Carolus On 4 April 2009 Leiden University, Leiden University Library, The Hortus botanicus and the Scaliger Institute 1526-1609 commemorate the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death with an exhibition The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius 1526-1609 and a reconstruction of the Clusius Garden. Clusius carolus clusius scaliger instituut clusius all3.indd 1 16-03-2009 10:38:21 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:11 Pagina 1 Kleine publicaties van de Leidse Universiteitsbibliotheek Nr. 80 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 2 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 3 The Exotic World of Carolus Clusius (1526-1609) Catalogue of an exhibition on the quatercentenary of Clusius’ death, 4 April 2009 Edited by Kasper van Ommen With an introductory essay by Florike Egmond LEIDEN UNIVERSITY LIBRARY LEIDEN 2009 binnenwerk.qxp 16-3-2009 11:12 Pagina 4 ISSN 0921-9293, volume 80 This publication was made possible through generous grants from the Clusiusstichting, Clusius Project, Hortus botanicus and The Scaliger Institute, Leiden. Web version: https://disc.leidenuniv.nl/view/exh.jsp?id=exhubl002 Cover: Jacob de Monte (attributed), Portrait of Carolus Clusius at the age of 59. -

Hieronymus Brunschwig (C. 1450–1513): His Life and Contributions to Surgery

Childs Nerv Syst (2012) 28:629–632 DOI 10.1007/s00381-011-1417-x CLASSICS IN PEDIATRIC NEUROSURGERY Hieronymus Brunschwig (c. 1450–1513): his life and contributions to surgery R. Shane Tubbs & Anand N. Bosmia & Martin M. Mortazavi & Marios Loukas & Mohammadali Shoja & Aaron A. Cohen Gadol Received: 17 November 2010 /Accepted: 25 February 2011 /Published online: 9 March 2011 # Springer-Verlag 2011 Abstract Henry Sigerist, the esteemed historian of medicine, makes a Introduction The objective of this paper to offer an brief note of the history of surgery on the European overview of the life and contributions of Hieronymus continent, writing that surgery began in Italy during the Brunschwig (also known as Jerome of Brunswick), a twelfth century and gradually spread to France and German surgeon of the fifteenth century, whose works Germany [4]. The German surgeons absorbed the discov- have provided insight into the practice of surgery during his eries and teachings of the Italian and French surgeons, and lifetime. these teachings became more accessible to the Germans Conclusions There is disagreement among academics about when German translations of the original Latin texts certain biographical details of Hieronymus Brunschwig’s became available in the fourteenth century. German surgery life. Regardless, Brunschwig’s productivity as an author remained purely receptive until the fifteenth century, when distinguishes him as a scholar in the field of surgery among attempts at literary achievement on the part of German the community of German surgeons in the fifteenth century. surgeons become visible [4]. Sigerist cites the example of His work offers important information about the practice of Heinrich von Pfalzpeunt, a Teutonic knight whose works, surgery in fifteenth-century Germany. -

H Erbals & M Edical Botany

Herbals & medical botany Herbals & medical botany e-catalogue Jointly offered for sale by: Extensive descriptions and images available on request All offers are without engagement and subject to prior sale. All items in this list are complete and in good condition unless stated otherwise. Any item not agreeing with the description may be returned within one week after receipt. Prices are EURO (€). Postage and insurance are not included. VAT is charged at the standard rate to all EU customers. EU customers: please quote your VAT number when placing orders. Preferred mode of payment: in advance, wire transfer or bankcheck. Arrangements can be made for MasterCard and VisaCard. Ownership of goods does not pass to the purchaser until the price has been paid in full. General conditions of sale are those laid down in the ILAB Code of Usages and Customs, which can be viewed at: <http://www.ilab.org/eng/ilab/code.html> New customers are requested to provide references when ordering. Orders can be sent to either firm. Antiquariaat FORUM BV ASHER Rare Books Tuurdijk 16 Tuurdijk 16 3997 ms ‘t Goy – Houten 3997 ms ‘t Goy – Houten The Netherlands The Netherlands Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Phone: +31 (0)30 6011955 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 Fax: +31 (0)30 6011813 E–mail: [email protected] E–mail: [email protected] Web: www.forumrarebooks.com Web: www.asherbooks.com www.forumislamicworld.com cover image: no. 17 v 1.0 · 14 Mar 2019 265 beautiful botanical lithographs of medicinal plants, coloured by hand as published 1. A NSLIJN, Nicolaas Nicolasz. -

HUNTIA a Journal of Botanical History

HUNTIA A Journal of Botanical History VOLUME 16 NUMBER 2 2018 Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, a research division of Carnegie Mellon University, specializes in the history of botany and all aspects of plant science and serves the international scientific community through research and documentation. To this end, the Institute acquires and maintains authoritative collections of books, plant images, manuscripts, portraits and data files, and provides publications and other modes of information service. The Institute meets the reference needs of botanists, biologists, historians, conservationists, librarians, bibliographers and the public at large, especially those concerned with any aspect of the North American flora. Huntia publishes articles on all aspects of the history of botany, including exploration, art, literature, biography, iconography and bibliography. The journal is published irregularly in one or more numbers per volume of approximately 200 pages by the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation. External contributions to Huntia are welcomed. Page charges have been eliminated. All manuscripts are subject to external peer review. Before submitting manuscripts for consideration, please review the “Guidelines for Contributors” on our Web site. Direct editorial correspondence to the Editor. Send books for announcement or review to the Book Reviews and Announcements Editor. All issues are available as PDFs on our Web site. Hunt Institute Associates may elect to receive Huntia as a benefit of membership; contact the Institute for more information. Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University 5th Floor, Hunt Library 4909 Frew Street Pittsburgh, PA 15213-3890 Telephone: 412-268-2434 Email: [email protected] Web site: http://www.huntbotanical.org Editor and layout Scarlett T. -

If You Are Inside Perusing Catalogs These Cold January Days, You May Have Wondered Why Asters Have Wandered

Not Just Cats Are Curious! If you are inside perusing catalogs these cold January days, you may have wondered why Asters have wandered. For example, the native blue wood aster is now classified Symphyotrichum cordifolium: also roses and such disparate items as cannabis and nettles belong to the same order? Being curious, you have known the impact on what we thought we knew by the discoveries of the human genome project. I understand none of this stellar achievement but I accept the fact that the influence of such a project has filtered into other areas of human knowledge – into the taxonomy of plants. The result is a new system and even the venerable Oxford Botanic Garden, established in 1621 “so that learning may be improved”, is renaming and rearranging. All of this proves Aristotle’s dictum “All men by nature desire to know.” Even before Aristotle (384-322 BC) men classified plants using contrast and difference in their descriptions, what it was and what it was not. There was never an era where the desire to know the nature and uses of plant material faltered. Along with the burgeoning of the desire to know all about everything that exploded with the Renaissance was the desire of apothecaries and plant enthusiasts to know what to call a plant. Seeds, plants, and especially bulbs had followed the Silk Road from East to West and the treasures had left their names behind with the language in which they had meaning. As the plants passed from owner to owner they were described of course and given names which were an attempt to pin down their distinctive characteristics. -

Maura C. Flannery St

Goethe and the Molecular Aesthetic Maura C. Flannery St. John’s University I argue here that Goethe’s “delicate empiricism” is not an alternative approach to science, but an approach that scientists use consistently, though they usually do not label it as such. I further contend that Goethe’s views are relevant to today’s science, specifically to work on the structure of macromolecules such as proteins. Using the work of Agnes Arber, a botanist and philosopher of science, I will show how her writings help to relate Goethe’s work to present-day issues of cogni- tion and perception. Many observers see Goethe’s “delicate empiricism” as an antidote to reductionism and to the strict separation of the objective and subjective so prevalent in science today. The argument is that there is a different way to do science, Goethe’s way, and it can achieve discoveries which would be impossible with more positivistic approaches. While I agree that Goethe’s method of doing science can be viewed in this light, I would like to take a different approach and use the writings of the plant morphologist Agnes Arber in the process since she worked in the Goethean tradition and en- larged upon it. I argue here that Goethe’s way of science is done by many, if not most scientists, that there is not a strict dichotomy between these two ways of doing science, but rather scientists move between the two approaches so frequently and the shift is so seamless that it is difficult for them to even realize that it is happening. -

Reader 19 05 19 V75 Timeline Pagination

Plant Trivia TimeLine A Chronology of Plants and People The TimeLine presents world history from a botanical viewpoint. It includes brief stories of plant discovery and use that describe the roles of plants and plant science in human civilization. The Time- Line also provides you as an individual the opportunity to reflect on how the history of human interaction with the plant world has shaped and impacted your own life and heritage. Information included comes from secondary sources and compila- tions, which are cited. The author continues to chart events for the TimeLine and appreciates your critique of the many entries as well as suggestions for additions and improvements to the topics cov- ered. Send comments to planted[at]huntington.org 345 Million. This time marks the beginning of the Mississippian period. Together with the Pennsylvanian which followed (through to 225 million years BP), the two periods consti- BP tute the age of coal - often called the Carboniferous. 136 Million. With deposits from the Cretaceous period we see the first evidence of flower- 5-15 Billion+ 6 December. Carbon (the basis of organic life), oxygen, and other elements ing plants. (Bold, Alexopoulos, & Delevoryas, 1980) were created from hydrogen and helium in the fury of burning supernovae. Having arisen when the stars were formed, the elements of which life is built, and thus we ourselves, 49 Million. The Azolla Event (AE). Hypothetically, Earth experienced a melting of Arctic might be thought of as stardust. (Dauber & Muller, 1996) ice and consequent formation of a layered freshwater ocean which supported massive prolif- eration of the fern Azolla. -

Of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation

Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Vol. 26, No. 1 Bulletin Spring 2014 of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Inside 4 Duets on display 4 Open House 2014 4 William Andrew 4 Illustrated mushroom Archer papers books, part 2 Above right, Tulipe des jardins. Tulipa gesneriana L. [Tulipa gesnerana Linnaeus, Liliaceae], stipple engraving on paper by P. F. Le Grand, 49 × 32.5 cm, after an original by Gerard van Spaendonck (Holland/France, 1746–1822) for his Fleurs Sessinées d’après Nature (Paris, L’Auteur, au Jardin des Plantes, 1801, pl. 4), HI Art accession no. 2078. Below left, Parrot tulips [Tulipa Linnaeus, Liliaceae], watercolor on paper by Rose Pellicano (Italy/United States), 1998, 56 × 42.5 cm, HI Art accession no. 7405. News from the Art Department Duets exhibition opens The inspiration for the exhibition Duets 1746–1822) has done so with the began with two artworks of trumpet subtle tonality of a monochromatic vine, which were created by the stipple engraving and Rose Pellicano 18th-century, German/English artist (Italy/United States) with rich layers Georg Ehret and the contemporary of watercolor. The former inspired Italian artist Marilena Pistoia. Visitors a legion of botanical artists while frequently request to view a selection teaching at the Jardin des Plantes in of the Institute’s collection of 255 Ehret Paris, and the latter, whose work is and 227 Pistoia original paintings. One inspired by French 18th- and 19th- day we displayed side-by-side the two century artists, carries on this tradition paintings (above left and right) and noticed of exhibiting, instructing and inspiring not only the similarity of composition up-and-coming botanical artists.