The Great Escape Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

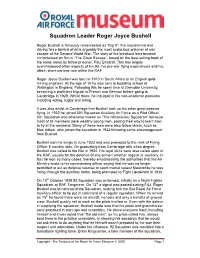

Squadron Leader Roger Joyce Bushell

Squadron Leader Roger Joyce Bushell Roger Bushell is famously remembered as “Big X”, the mastermind and driving force behind what is arguably the most audacious prisoner of war escape of the Second World War. The story of the breakout later became immortalized on film in “The Great Escape”, based on the best-selling book of the same name by fellow prisoner, Paul Brickhill. This has largely overshadowed other aspects of his life, his pre-war flying experiences and his, albeit, short wartime role within the RAF. Roger Joyce Bushell was born in 1910 in South Africa to an English gold- mining engineer. At the age of 10 he was sent to boarding school at Wellington in England. Following this he spent time at Grenoble University, becoming a proficient linguist in French and German before going to Cambridge in 1929. Whilst there, he indulged in his non-academic passions including acting, rugby and skiing. It was also whilst at Cambridge that Bushell took up his other great passion: flying. In 1932 he joined 601 Squadron Auxiliary Air Force as a Pilot Officer. 601 Squadron was otherwise known as “The Millionaires’ Squadron” because most of its members were wealthy young men, paying their way to learn how to fly at the weekend. Many of these men were also fellow skiers, such as Max Aitken, who joined the squadron in 1934 following some encouragement from Bushell. Bushell won his wings in June 1933 and was promoted to the rank of Flying Officer 8 months later. On graduating from Cambridge with a law degree, Bushell was called to the Bar in 1934. -

Tunnel Systems . Design & Supply

Business Location Zweibrücken Sales Office Vienna, Austria Business Location Chengdu, China (Joint Venture) Headquarters Power, Mining, Tunnel and Chengdu KK&K Power Fan Co., Ltd. Power, Mining and Tunnel Fans, Industrial Fans Sales, Service, Engineering, Manufacture Service Sales, Service No. 15 Wukexisilu, Wuhou Disctrict, Gleiwitzstrasse 7 Karl-Waldbrunner-Platz 1 Chengdu 61 0045 66482 Zweibrücken/Germany 121 0 Vienna /Austria Sichuan Province/P.R. China Phone: +49 6332 808-0 Phone: +43 1713 403010 Phone: +86 28 85003500 Business Location Bad Hersfeld Rep. Office Moscow, Russia Business Location Akron, OH USA Manufacture and Logistics, Power, Mining, Tunnel and TLT-Turbo Inc. Industrial Fans, Service Industrial Fans Power, Mining, Tunnel and Wippershainer Strasse 51 ul. Novoslabodskaya 31,d.4 Industrial Fans 36251 Bad Hersfeld/Germany 127055 Moscow/Russia Sales, Service, Manufacture Phone: +49 6621 7962-0 Phone: +7 459 6611780 2693 Wingate Avenue Akron, OH 44314/USA Business Location Frankenthal Sales Office Beijing, China Phone: +1 844-858-3267 (844-TLT-Fans) Service, Power Fans TLT-Turbo GmbH Hessheimer Strasse 2 Beijing Representative Office Business Location TLT ACTOM (Pty) Ltd, South Africa 67227 Frankenthal/Germany Sales Industrial Fans (Joint Venture) Phone: +49 6233 77081-0 22 D Building E Sales, Service, Manufacture Majestic Garden No. 6 Magnet House Business Location Oberhausen North Sichuan Medium Road 4 Branch Road Service, Power Fans Chaoyang District Driehoek Havensteinstrasse 46 100029 Beijing /P.R. China Germiston, 1401 46045 Oberhausen/Germany Phone: +86 10 82842683/84 Phone: +27 11 878-3050 Phone: +49 208 8592-0 www.tlt-actom.co.za Sweden Russia Canada Germany Benelux Poland Mongolia Ukraine Slovakia Spain Italy Czech Republic USA Turkey Korea China Israel Egypt Taiwan Indonesia Columbia Venezuela Peru Brazil Australia Chile Mexico South Africa Guatemala Honduras Nicaragua TLT-Turbo GmbH representatives Tunnel Systems . -

Gotham Games Ships the Great Escape for Playstation 2, Xbox and PC

Gotham Games Ships The Great Escape for PlayStation 2, Xbox and PC July 23, 2003 8:34 AM ET NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--July 23, 2003-- Featuring The Virtual Return of Steve McQueen, Gotham Games and MGM Interactive Deliver the Classic Title of the Summer Gotham Games, a publishing label of Take-Two Interactive Software, Inc. (NASDAQ:TTWO), announced today that The Great Escape, based on the classic 1963 Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Film, has shipped to retail outlets nationwide for the PlayStation(R)2 computer entertainment system, Xbox(TM) video game system from Microsoft(TM) and PC. One of the most celebrated tough-guys of American cinema, Steve McQueen makes a triumphant return as he is digitally recreated to reprise his unforgettable role as Captain Virgil "the Cooler King" Hilts in The Great Escape. Utilizing McQueen's likeness, The Great Escape puts gamers in control of Hilts and his band of POWs as they break free from the notorious Stalag Luft III prison camp and battle the Nazis throughout WWII. Gamers will combat the evil Third Reich in fistfights, shootouts and high-speed chases through 18 unique levels of adrenaline-filled stealth and combat-based gameplay. Throughout The Great Escape, players will control multiple characters, each with their own individual strengths and abilities, through a variety of levels. McQueen's character Hilts, "The Cooler King," has a knack for picking locks. MacDonald, known as "Intelligence," can speak German to impersonate Nazi soldiers, and Hendley, "The Scrounger," is a master pickpocket. The diverse and beautifully rendered levels include a German POW camp, a mountaintop castle-fortress, a moving train and an active Luftwaffe airfield. -

A “POW Rolex” Recalls the Great

A “POW Rolex” Recalls the Great Escape by Alan Downing Click the images to view larger versions On May 12-13 th, Antiquorum Geneva will hold its second auction of 2007, in which nearly 696 watches and clocks will be auctioned off. On this occasion, two lots, No 311 and 312 will be sold and we are proud to share with you the wonderful story of lot No. 311. We warmly thank Mr Alan Downing, who we met at our Antiquorum Office in Geneva three weeks ago, for sharing with us the exceptional story of this Pow Rolex. Following a very interesting discussion with Mr Downing and thanks to the rich illustrative material he provided us with, we hereby present the story of this Rolex Oyster which belonged to Mr Clive James Nutting, Corporal in the Royal Corps of Signals, who was a prisoner in Stalag Luft III from 1939 to 1945. This essay written by Alan tells us the story of Clive Nutting and shows how Rolex (and other watch factories) were engaged in the regular supply of watches to men incarcerated in Prisoner of War camps like Stalag Luft III (located at Sagan, 100 miles southeast of Berlin, at present Poland). This camp is probably the most famous of all Prisoner of War Camps due to it being the scene of the great escape of march 1944 and the subsequent making of the 1962 film of the same name. We are pleased to share this story, provided by Alan, and photos with the TimeZone community in advance of the catalog's publication. -

Prisoners of War 1915 – 1945

“In the Bag”: Prisoners of War 1915 – 1945 “IN THE BAG”: PRISONERS OF WAR 1915 - 1945 THE PROCEEDINGS OF THE CONFERENCE HELD AT THE POMPEY ELLIOT MEMORIAL HALL, CAMBERWELL RSL BY MILITARY HISTORY AND HERITAGE, VICTORIA. 12 NOVEMBER 2016 Proudly supported by: “In the Bag”: Prisoners of War 1915 – 1945 One of ‘The Fifty’- Understanding the human cost of The Great Escape through the relics of Squadron Leader James Catanach DFC Neil Sharkey A lot of people know about the Great Escape and their most important source of information is this document :- And the detail of the escape they remember most, is this one. “In the Bag”: Prisoners of War 1915 – 1945 I really shouldn’t make light of one of the Second World War’s most fascinating and tragic episodes and only do so to make the point that the film was made as entertainment. Many aspects of the story were altered for commercial reasons. None of the actual escapees were American, for instance, and none of the escape attempts involved stolen motorcycles, or hijacked Messerschmitts. Most characters in the film were amalgams of many men rather than single individuals and the ‘The Fifty’ to who the film is dedicated were not machine- gunned in one place at the same time, as depicted in the film, but shot in small groups, in different locales, over many days. Much of what the film does depict, however, is correct, the way sought-after items—tools, identity papers, supplies—were fabricated or otherwise obtained, as well as, the inventive technologies employed in the planning of the escape and the construction of the tunnel. -

Trend Analysis of Long Tunnels Worldwide

Trend Analysis of Long Tunnels Worldwide MTI Report WP 12-09 MINETA TRANSPORTATION INSTITUTE The Mineta Transportation Institute (MTI) was established by Congress in 1991 as part of the Intermodal Surface Transportation Equity Act (ISTEA) and was reauthorized under the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st century (TEA-21). MTI then successfully competed to be named a Tier 1 Center in 2002 and 2006 in the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users (SAFETEA-LU). Most recently, MTI successfully competed in the Surface Transportation Extension Act of 2011 to be named a Tier 1 Transit-Focused University Transportation Center. The Institute is funded by Congress through the United States Department of Transportation’s Office of the Assistant Secretary for Research and Technology (OST-R), University Transportation Centers Program, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans), and by private grants and donations. The Institute receives oversight from an internationally respected Board of Trustees whose members represent all major surface transportation modes. MTI’s focus on policy and management resulted from a Board assessment of the industry’s unmet needs and led directly to the choice of the San José State University College of Business as the Institute’s home. The Board provides policy direction, assists with needs assessment, and connects the Institute and its programs with the international transportation community. MTI’s transportation policy work is centered on three primary responsibilities: Research MTI works to provide policy-oriented research for all levels of Department of Transportation, MTI delivers its classes over government and the private sector to foster the development a state-of-the-art videoconference network throughout of optimum surface transportation systems. -

Geoffrey Wellum: the Battle of Britain’S Youngest Warrior

Never StillStay Geoffrey Wellum: The Battle of Britain’s Youngest Warrior BY RACHEL MORRIS As Hitler’s tanks roll into Poland on September 1, 1939, Europe’s worst fears are confi rmed: war becomes inevitable. A thousand miles away, a young man celebrates his fi rst solo fl ight in a de Havilland Tiger Moth, heading to a quiet English country pub with friends to enjoy a pint of beer. As his training continues, the mighty German Blitzkrieg sweeps across the continent. Soon he will earn his coveted Royal Air Force pilot wings in time to join the most epic aerial battle of history: defending the green fi elds of his homeland from the Luftwaff e foe determined to clear the path for invasion. Interviewed in London’s RAF Club in 2012, Geoff rey Wellum recounted his experiences as the youngest pilot to fl y and fi ght during the Battle of Britain. 22 fl ightjournal.com 2 Never Stay Still.indd 22 7/16/13 2:52 PM Spitfi re Mk I P9374 comes in to land at Duxford, England on a fall evening. No. 92 Squadron fi rst received Spitfi res in early 1940 and fl ew various marks throughout the war. Wellum was struck by the machine’s great beauty but regretted they had to use such a wonderful aircraft as a weapon of war. (Photo by John Dibbs/planepicture.com) SPITFIRE 23 2 Never Stay Still.indd 23 7/16/13 2:52 PM Never stay still East India Flying Squadron gets Scrambled again in the afternoon, the squad- blooded ron suffered further losses with Flight Lieuten- After completing advanced pilot training, Wel- ant Paddy Green badly wounded, Sergeant Paul lum was posted straight to No. -

Source N - Great Escape Article from Mail Online by Phil Craig

Wartime West Sussex 1939 - 1945 The Great Escape case study Source N - Great Escape article from Mail Online by Phil Craig The story starts with a classic moment of British derring-do - what Hollywood rightly christened The Great Escape. On March 24, 1944, 76 Allied airmen, mostly RAF officers, crawled along a tunnel deep beneath the forbidding fences and deadly machine-gun towers of the Stalag Luft III PoW camp and escaped to freedom. Unfortunately, the tunnel was discovered half way through the break-out and many more got left behind. Among them was 21- year-old Flight Lieutenant Alan Bryett. Today, sitting in his home in Bromley, Bryett smiles at the recollection of their extraordinary escapade - and the courage of its leader, Squadron Leader Roger Bushell, 'the bravest man I ever knew'. He also insists that Bushell never took the terrible risks they faced for granted. 'I remember him telling us that we couldn't run an escape like this without one or two of us being killed.' Hero: British prisoner-of-war Roger Bushell was shot by the Nazis in 1944 after attempting to escape Unfortunately, however, it wasn't just one or two who lost their lives. In the end, 50 of the escapees, including Squadron Leader Bushell, were murdered by the Germans. Imprisoned since 1940, Bushell was a driven man and a fanatical escaper. One previous attempt had ended in tragedy when the Czech family sheltering him were rounded up and executed, so Bushell knew exactly what the enemy was capable of. He had also been warned that his next escape would be his last. -

Island Farm Camp

UNITED KINGDOM On the A48. just outside the town of Bridgend, in South Wales, the traveller may note a group of battered and overgrown huts, the access to which is barred by a hedge and two twisted gate posts with a length of rusty chain strung between them. No indica ISLAND FARM CAMP tion is present from the road as to the ment for crops, but the subsoil is yellow- historical significance of the place, which is orange clay, a detail of some importance as By Jeff Vincent known as Island Farm. Indeed, apart from we shall see. The terrain is slowly undulat some of the local community, few people ing, gently rising from the north side, the floor. Some buildings, of special use, do not appreciate that Island Farm Prisoner-of-War side of the A48 and the camp entrance, conform to this pattern. Amongst these are Camp saw one of the biggest escape attempts towards the sea (which is only three miles the Motor Transport (MT) shed, the cook of the Second World War by German prison away). house, laundry, HQ block, and two wooden ers and was the home for two years to most The layout of the camp is fairly typical of structures at opposite ends of the camp, one of Hitler’s senior officers. It still stands its time. The accommodation huts were built used as a coffee shop and the other as a tailor virtually untouched. in prefabricated materials; they represent and barber’s shop. On the higher side of the The camp was built of prefabricated huts ‘wings’ of the central ablution block which camp a larger than average hut was built, on rich agricultural land in one of the prime was built of red brick. -

Great Escape

Serenity Assisted L i v i n g & M e m o r y C a r e Dilworth, MN Great Escape Points of On March 24, 1944, the British bomber pilot Leslie “Johnny” Bull poked his Interest: head out of the ground and took his first breath of freedom after suffering as a prisoner of war in the Nazi-controlled Stalag Luft III camp. The so-called “Great • March Escape” had begun, one of the most daring mass breakouts ever attempted during wartime. Birthdays In 1944, the camp housed over 10,000 Allied service members. The location of the camp was chosen in part due to its sandy soil, which made any attempts to • Activity tunnel out extremely difficult. This did not deter Royal Air Force Squadron Leader Calendar Roger Bushell from devising a grand tunneling scheme. His plan consisted of “three bloody deep, bloody long tunnels,” code-named Tom, Dick, and Harry. Previous • Snapshot escapes had been attempted, but none on the scale Bushell proposed. Not only Photos did he oversee the excavation of three tunnels but he also devised a system of signals that allowed POWs to track prison guards and communicate their wherea- bouts. He also procured civilian clothes for escapees, forged travel documents, and • Movies of equipment for the 600 digging inmates. As the plan’s mastermind, Bushell was given the Month the code name “Big X.” His plan proved ingenious. Powdered milk cans dis- tributed by the Red Cross were fashioned into shovels, picks, and lanterns. Excavated dirt was smuggled to the surface inside inmates’ trouser legs and then scattered while the prisoners walked around. -

Flightlines JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2018

Saturday April 28, 2018 LIVE & SILENT AUCTION BUY TICKETS NOW!! SAVE+WIN!! EARLY BUY DEAL $3999 $29999 (until March 31st) per person OR table of 8 includes chance for trip prize - reg. $49.99 reg. $399.99 All tickets to this casual event include buffet dinner & wine. Amazing Prizes to be Won including a Private Tour of Jay Leno’s Personal Garage* *Items subject to change without notice. 9280 Airport Road Mount Hope, Ontario, L0R 1W0 warplane.com Fundraiser supporting the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum plus Help A Child Smile President & Chief Executive Officer David G. Rohrer Vice President – Facilities Manager Controller Operations Cathy Dowd Brenda Shelley Pam Rickards Curator Education Services Vice President – Finance Erin Napier Manager Ernie Doyle Howard McLean Flight Coordinator Chief Engineer Laura Hassard-Moran Donor Services Jim Van Dyk Manager Retail Manager Sally Melnyk Marketing Manager Shawn Perras Al Mickeloff Building Maintenance Volunteer Services Manager Food & Beverage Manager Administrator Jason Pascoe Anas Hasan Toni McFarlane Board of Directors Christopher Freeman, Chair Nestor Yakimik Art McCabe David Ippolito Robert Fenn Dennis Bradley, Ex Officio John O’Dwyer Marc Plouffe Sandy Thomson, Ex Officio David G. Rohrer Patrick Farrell Bruce MacRitchie, Ex Officio Stay Connected Subscribe to our eFlyer Canadian Warplane warplane.com/mailing-list-signup.aspx Heritage Museum 9280 Airport Road Read Flightlines online warplane.com/about/flightlines.aspx Mount Hope, Ontario L0R 1W0 Like us on Facebook facebook.com/Canadian Phone 905-679-4183 WarplaneHeritageMuseum Toll free 1-877-347-3359 (FIREFLY) Fax 905-679-4186 Follow us on Twitter Email [email protected] @CWHM Web warplane.com Watch videos on YouTube youtube.com/CWHMuseum Shop our Gift Shop warplane.com/gift-shop.aspx Follow Us on Instagram instagram.com/ canadianwarplaneheritagemuseum Volunteer Editor: Bill Cumming Flightlines is the official publication of the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum. -

The History of the Middle Finger. the Great Escape

RAAF Radschool Association Magazine – Vol 25 Page 16 The History of the Middle Finger. Before the Battle of Agincourt in October 1415, the French, anticipating victory over the English, proposed to cut off the middle finger of all captured English soldiers. Without the middle finger it would be impossible to draw the renowned English longbow and therefore they would be incapable of fighting in the future. This famous English longbow was made of the native English Yew tree, and the act of drawing the longbow was known as 'plucking the yew' (or 'pluck yew'). Much to the bewilderment of the French, the English won a major upset and began mocking the French by waving their middle fingers at the defeated French, saying, See, we can still pluck yew! Since 'pluck yew' is rather difficult to say, the difficult consonant cluster at the beginning has gradually changed to a labiodentals fricative F', and thus the words often used in conjunction with the one-finger-salute! It is also because of the pheasant feathers on the arrows used with the longbow that the symbolic gesture is known as 'giving the bird.' It is still an appropriate salute to the French today! The above has been sent to us by a number of people, however, although it is a great yarn, it’s all garbage and completely untrue. We’ve only included it because it’s a helluva story………and why let the truth interfere… The Great Escape. Most will remember seeing the 1963 movie “The Great Escape” which starred the late Steve McQueen, James Garner, Richard Attenborough, James Coburn and others.