Methods in Language Documentation and Description: a Guide to the Kelabit Documentation Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petualangan Unjung Dan Mbui Kuvong

PETUALANGAN UNJUNG DAN MBUI KUVONG Naskah dan Dokumen Nusantara XXXV PETUALANGAN UNJUNG DAN MBUI KUVONG SASTRA LISAN DAN KAMUS PUNAN TUVU’ DARI Kalimantan dikumpulkan dan disunting oleh Nicolas Césard, Antonio Guerreiro dan Antonia Soriente École française d’Extrême-Orient KPG (Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia) Jakarta, 2015 Petualangan Unjung dan Mbui Kuvong: Sastra Lisan dan Kamus Punan Tuvu’ dari Kalimantan dikumpulkan dan disunting oleh Nicolas Césard, Antonio Guerreiro dan Antonia Soriente Hak penerbitan pada © École française d’Extrême-Orient Hak cipta dilindungi Undang-undang All rights reserved Diterbitkan oleh KPG (Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia) bekerja sama dengan École française d’Extrême-Orient Perancang Sampul: Ade Pristie Wahyo Foto sampul depan: Pemandangan sungai di Ulu Tubu (Dominique Wirz, 2004) Ilustrasi sampul belakang: Motif tradisional di balai adat Respen Tubu (Foto A. Soriente, 2011) Penata Letak: Diah Novitasari Cetakan pertama, Desember 2015 382 hlm., 16 x 24 cm ISBN (Indonesia): 978 979 91 0976 7 ISBN (Prancis): 978 2 85539 197 7 KPG: 59 15 01089 Alamat Penerbit: KPG (Kepustakaan Populer Gramedia) Gedung Kompas Gramedia, Blok 1 lt. 3 Jln. Palmerah Barat No. 29-37, JKT 10270 Tlp. 536 50 110, 536 50 111 Email: [email protected] Dicetak oleh PT Gramedia, Jakarta. Isi di luar tanggung jawab percetakan. DAFtaR ISI Daftar Isi — 5 Kata Sambutan — 7 - Robert Sibarani, Ketua Asosiasi Tradisi Lisan (ATL) Wilayah Sumatra Utara — 7 - Amat Kirut, Ketua Adat Suku Punan, Desa Respen Tubu, Kecamatan Malinau Utara, -

![Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4203/arxiv-2011-02128v1-cs-cl-4-nov-2020-234203.webp)

Arxiv:2011.02128V1 [Cs.CL] 4 Nov 2020

Cross-Lingual Machine Speech Chain for Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks Speech Recognition and Synthesis Sashi Novitasari1, Andros Tjandra1, Sakriani Sakti1;2, Satoshi Nakamura1;2 1Nara Institute of Science and Technology, Japan 2RIKEN Center for Advanced Intelligence Project AIP, Japan fsashi.novitasari.si3, tjandra.ai6, ssakti,[email protected] Abstract Even though over seven hundred ethnic languages are spoken in Indonesia, the available technology remains limited that could support communication within indigenous communities as well as with people outside the villages. As a result, indigenous communities still face isolation due to cultural barriers; languages continue to disappear. To accelerate communication, speech-to-speech translation (S2ST) technology is one approach that can overcome language barriers. However, S2ST systems require machine translation (MT), speech recognition (ASR), and synthesis (TTS) that rely heavily on supervised training and a broad set of language resources that can be difficult to collect from ethnic communities. Recently, a machine speech chain mechanism was proposed to enable ASR and TTS to assist each other in semi-supervised learning. The framework was initially implemented only for monolingual languages. In this study, we focus on developing speech recognition and synthesis for these Indonesian ethnic languages: Javanese, Sundanese, Balinese, and Bataks. We first separately train ASR and TTS of standard Indonesian in supervised training. We then develop ASR and TTS of ethnic languages by utilizing Indonesian ASR and TTS in a cross-lingual machine speech chain framework with only text or only speech data removing the need for paired speech-text data of those ethnic languages. Keywords: Indonesian ethnic languages, cross-lingual approach, machine speech chain, speech recognition and synthesis. -

The Status of the Least Documented Language Families in the World

Vol. 4 (2010), pp. 177-212 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/ http://hdl.handle.net/10125/4478 The status of the least documented language families in the world Harald Hammarström Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen and Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, Leipzig This paper aims to list all known language families that are not yet extinct and all of whose member languages are very poorly documented, i.e., less than a sketch grammar’s worth of data has been collected. It explains what constitutes a valid family, what amount and kinds of documentary data are sufficient, when a language is considered extinct, and more. It is hoped that the survey will be useful in setting priorities for documenta- tion fieldwork, in particular for those documentation efforts whose underlying goal is to understand linguistic diversity. 1. InTroducTIon. There are several legitimate reasons for pursuing language documen- tation (cf. Krauss 2007 for a fuller discussion).1 Perhaps the most important reason is for the benefit of the speaker community itself (see Voort 2007 for some clear examples). Another reason is that it contributes to linguistic theory: if we understand the limits and distribution of diversity of the world’s languages, we can formulate and provide evidence for statements about the nature of language (Brenzinger 2007; Hyman 2003; Evans 2009; Harrison 2007). From the latter perspective, it is especially interesting to document lan- guages that are the most divergent from ones that are well-documented—in other words, those that belong to unrelated families. I have conducted a survey of the documentation of the language families of the world, and in this paper, I will list the least-documented ones. -

School of Psychology and Speech Pathology

School of Psychology and Speech Pathology Talking about health, wellbeing and disability in young people: an Aboriginal perspective Caris Lae Jalla This thesis is presented for the Degree of Master of Philosophy of Curtin University February 2016 DECLARATION To the best of my knowledge and belief this thesis contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgment has been made. This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university. Signature: Caris Jalla Date: ii ABSTRACT In many Indigenous languages globally, there is often no directly translatable word for disability. For Australian Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, the prevalence of disability is greater compared to non-Indigenous populations. Despite the gap in rates, access to disability supports and services are lower and disproportional. One factor impacting low service access may be the differing views of disability between Aboriginal and Torres Strait cultures and mainstream Western perspectives. The objectives of this research were to investigate the meaning of health, wellbeing and disability from the viewpoint of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youths and to describe the facilitators and barriers to health and wellbeing for people with disabilities. These investigations also identified Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and young people’s perceptions on the causes of disability and explored concepts associated with living with disability. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youths, both with and without disabilities, residing in Perth, Western Australia (WA) and aged nine to 26 years were invited to participate in qualitative research. Yarning circles were conducted in various home and community settings around the metropolitan area. -

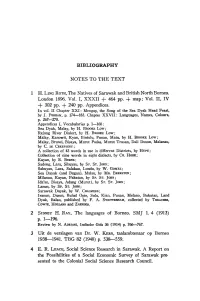

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia)

Empowered lives. Resilient nations. FORUM MASYARAKAT ADAT DATARAN TINGGI BORNEO (FORMADAT) Borneo (Indonesia & Malaysia) Equator Initiative Case Studies Local sustainable development solutions for people, nature, and resilient communities UNDP EQUATOR INITIATIVE CASE STUDY SERIES Local and indigenous communities across the world are 126 countries, the winners were recognized for their advancing innovative sustainable development solutions achievements at a prize ceremony held in conjunction that work for people and for nature. Few publications with the United Nations Convention on Climate Change or case studies tell the full story of how such initiatives (COP21) in Paris. Special emphasis was placed on the evolve, the breadth of their impacts, or how they change protection, restoration, and sustainable management over time. Fewer still have undertaken to tell these stories of forests; securing and protecting rights to communal with community practitioners themselves guiding the lands, territories, and natural resources; community- narrative. The Equator Initiative aims to fill that gap. based adaptation to climate change; and activism for The Equator Initiative, supported by generous funding environmental justice. The following case study is one in from the Government of Norway, awarded the Equator a growing series that describes vetted and peer-reviewed Prize 2015 to 21 outstanding local community and best practices intended to inspire the policy dialogue indigenous peoples initiatives to reduce poverty, protect needed to take local success to scale, to improve the global nature, and strengthen resilience in the face of climate knowledge base on local environment and development change. Selected from 1,461 nominations from across solutions, and to serve as models for replication. -

HOW UNIVERSAL IS AGENT-FIRST? EVIDENCE from SYMMETRICAL VOICE LANGUAGES Sonja Riesberg Kurt Malcher Nikolaus P

HOW UNIVERSAL IS AGENT-FIRST? EVIDENCE FROM SYMMETRICAL VOICE LANGUAGES Sonja Riesberg Kurt Malcher Nikolaus P. Himmelmann Universität zu Köln and Universität zu Köln Universität zu Köln The Australian National University Agents have been claimed to be universally more prominent than verbal arguments with other thematic roles. Perhaps the strongest claim in this regard is that agents have a privileged role in language processing, specifically that there is a universal bias for the first unmarked argument in an utterance to be interpreted as an agent. Symmetrical voice languages such as many western Austronesian languages challenge claims about agent prominence in various ways. Inter alia, most of these languages allow for both ‘agent-first’ and ‘undergoer-first’ orders in basic transitive con - structions. We argue, however, that they still provide evidence for a universal ‘agent-first’ princi - ple. Inasmuch as these languages allow for word-order variation beyond the basic set of default patterns, such variation will always result in an agent-first order. Variation options in which un - dergoers are in first position are not attested. The fact that not all transitive constructions are agent-first is due to the fact that there are competing ordering biases, such as the principles dictat - ing that word order follows constituency or the person hierarchy, as also illustrated with Aus - tronesian data.* Keywords : agent prominence, person prominence, word order, symmetrical voice, western Aus - tronesian 1. Introduction. Natural languages show a strong tendency to place agent argu - ments before other verbal arguments, as seen, inter alia, in the strong predominance of word-order types in which S is placed before O (SOV, SVO, and VSO account for more than 80% of the basic word orders attested in the languages of the world; see Dryer 2013). -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Computational Linguistics Research on Philippine Languages

Computational Linguistics Research on Philippine Languages Rachel Edita O. ROXAS Allan BORRA Software Technology Department Software Technology Department De La Salle University De La Salle University 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines 2401 Taft Avenue, Manila, Philippines [email protected] [email protected] languages spoken in Southern Philippines. But Abstract as of yet, extensive research has already been done on theoretical linguistics and little is This is a paper that describes computational known for computational linguistics. In fact, the linguistic activities on Philippines computational linguistics researches on languages. The Philippines is an archipelago Philippine languages are mainly focused on 1 with vast numbers of islands and numerous Tagalog. There are also notable work done on languages. The tasks of understanding, Ilocano. representing and implementing these Kroeger (1993) showed the importance of the languages require enormous work. An grammatical relations in Tagalog, such as extensive amount of work has been done on subject and object relations, and the understanding at least some of the major insufficiency of a surface phrase structure Philippine languages, but little has been paradigm to represent these relations. This issue done on the computational aspect. Majority was further discussed in the LFG98, which is on of the latter has been on the purpose of the problem of voice and grammatical functions machine translation. in Western Austronesian Languages. Musgrave (1998) introduced the problem certain verbs in 1 Philippine Languages these languages that can head more than one transitive clause type. Foley (1998) and Kroeger Within the 7,200 islands of the Philippine (1998), in particular, discussed about long archipelago, there are about one hundred and debated issues such as nouns in Tagalog that can one (101) languages that are spoken. -

Borneo Research Bulletin Is Published Twice Yearly (April and Septemb-The Research Council

BORNEO RESEARCH BULLET11 Vol. 11, No. 1 April 1979 Notes frool the Editor: UNESCO Grant for En-t Drive; Contributions for the Support of the BRC --Research Notes Ecological Determinism: Is the Appell Hypothesis Valid? ...........Joseph B. Weinstock An Efko-history of the Kelabit Tribe of Sarawak: A Brief Look at the Kelabit Tribe Before World War I1 and After . Robert Lian - Robert Saging Brief Cammications Indonesian Forestry at a Glance ......... Distribution and Status of the Asian Elephant: Borneo ...................... --News and Announcements lhmn Ecology and ?kcmmic Developnent in Kali- mantan and Sunntra .......Andrew P. Vayda Royal Geographical Society's Symposium on Gunong WuNational Park, Sarawak . A. Clive Jenny --Book Reviews, Abstracts, Bibliography The Borneo Research Bulletin is published twice yearly (April and Septemb-the Research Council. Please address all inquiries and contributions for publications to Vinson H. Sutlive, Jr., Editor, Borneo Research Bulletin, Department of Anthapolo College mliaman .liamsburg, Vir- ginia, 231g: U. S. A. Single issu:s% available at US$ 2.50. --hVI"dS -FROM ?HE q RESZARCH NOTES 1 The Borneo Research Counci~maownent Fbna 1s ar: hehalf-way mark our projected goal of US$ 10.000. In Nwember 1978. James F. rivitt, "camending the efforts of the Borneo Research Council in ECOLOGICAL LNzmmmISM: producing the twice yearly bulletin," encouraged the Division of Ecological Sciences, United Nations Educational, Scientific and IS THE APmHYPOTHESIS VALID? Cultural Organization, to provide contractual support towards the Endomcent hdof the Council. In his letter of January 19, 1979, Malcolm Hadley of the Division of Ecological Sciences, writing that Joseph A. Weinstock his division was "iqressed with the presentation and content of Come11 University the Bulletin," notified the editor of a one-time grant of $800 for ' the En-t Fund. -

Resources for Philippine Languages: Collection, Annotation, and Modeling

PACLIC 30 Proceedings Resources for Philippine Languages: Collection, Annotation, and Modeling Nathaniel Ocoa, Leif Romeritch Syliongkaa, Tod Allmanb, Rachel Edita Roxasa aNational University 551 M.F. Jhocson St., Sampaloc, Manila, PH 1008 bGraduate Institute of Applied Linguistics 7500 W. Camp Wisdom Rd., Dallas, TX 75236 {nathanoco,lairusi,todallman,rachel_roxas2001}@yahoo.com The paper’s structure is as follows: section 2 Abstract discusses initiatives in the country and the various language resources we collected; section In this paper, we present our collective 3 discusses annotation and documentation effort to gather, annotate, and model efforts; section 4 discusses language modeling; various language resources for use in and we conclude our work in section 5. different research projects. This includes those that are available online such as 2 Collection tweets, Wikipedia articles, game chat, online radio, and religious text. The Research works in language studies in the different applications, issues and Philippines – particularly in language directions are also discussed in the paper. documentation and in corpus building – often Future works include developing a involve one or a combination of the following: language web service. A subset of the “(1) residing in the place where the language is resources will be made temporarily spoken, (2) working with a native speaker, or (3) available online at: using printed or published material” (Dita and http://bit.ly/1MpcFoT. Roxas, 2011). Among these, working with resources available is the most feasible option given ordinary circumstances. Following this 1 Introduction consideration, the Philippines as a developing country is making its way towards a digital age, The Philippines is a country in Southeast Asia which highlights – as Jenkins (1998) would put it composed of 7,107 islands and 187 listed – a “technological culture of computers”. -

Detailed Species Accounts from The

Threatened Birds of Asia: The BirdLife International Red Data Book Editors N. J. COLLAR (Editor-in-chief), A. V. ANDREEV, S. CHAN, M. J. CROSBY, S. SUBRAMANYA and J. A. TOBIAS Maps by RUDYANTO and M. J. CROSBY Principal compilers and data contributors ■ BANGLADESH P. Thompson ■ BHUTAN R. Pradhan; C. Inskipp, T. Inskipp ■ CAMBODIA Sun Hean; C. M. Poole ■ CHINA ■ MAINLAND CHINA Zheng Guangmei; Ding Changqing, Gao Wei, Gao Yuren, Li Fulai, Liu Naifa, Ma Zhijun, the late Tan Yaokuang, Wang Qishan, Xu Weishu, Yang Lan, Yu Zhiwei, Zhang Zhengwang. ■ HONG KONG Hong Kong Bird Watching Society (BirdLife Affiliate); H. F. Cheung; F. N. Y. Lock, C. K. W. Ma, Y. T. Yu. ■ TAIWAN Wild Bird Federation of Taiwan (BirdLife Partner); L. Liu Severinghaus; Chang Chin-lung, Chiang Ming-liang, Fang Woei-horng, Ho Yi-hsian, Hwang Kwang-yin, Lin Wei-yuan, Lin Wen-horn, Lo Hung-ren, Sha Chian-chung, Yau Cheng-teh. ■ INDIA Bombay Natural History Society (BirdLife Partner Designate) and Sálim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History; L. Vijayan and V. S. Vijayan; S. Balachandran, R. Bhargava, P. C. Bhattacharjee, S. Bhupathy, A. Chaudhury, P. Gole, S. A. Hussain, R. Kaul, U. Lachungpa, R. Naroji, S. Pandey, A. Pittie, V. Prakash, A. Rahmani, P. Saikia, R. Sankaran, P. Singh, R. Sugathan, Zafar-ul Islam ■ INDONESIA BirdLife International Indonesia Country Programme; Ria Saryanthi; D. Agista, S. van Balen, Y. Cahyadin, R. F. A. Grimmett, F. R. Lambert, M. Poulsen, Rudyanto, I. Setiawan, C. Trainor ■ JAPAN Wild Bird Society of Japan (BirdLife Partner); Y. Fujimaki; Y. Kanai, H.