The Machineries of Symbolic Power in Carnatic Music and Its Festivals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007

Copyright by Kristen Dawn Rudisill 2007 The Dissertation Committee for Kristen Dawn Rudisill certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT Committee: ______________________________ Kathryn Hansen, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Martha Selby, Co-Supervisor ______________________________ Ward Keeler ______________________________ Kamran Ali ______________________________ Charlotte Canning BRAHMIN HUMOR: CHENNAI’S SABHA THEATER AND THE CREATION OF MIDDLE-CLASS INDIAN TASTE FROM THE 1950S TO THE PRESENT by Kristen Dawn Rudisill, B.A.; A.M. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin December 2007 For Justin and Elijah who taught me the meaning of apu, pācam, kātal, and tuai ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I came to this project through one of the intellectual and personal journeys that we all take, and the number of people who have encouraged and influenced me make it too difficult to name them all. Here I will acknowledge just a few of those who helped make this dissertation what it is, though of course I take full credit for all of its failings. I first got interested in India as a religion major at Bryn Mawr College (and Haverford) and classes I took with two wonderful men who ended up advising my undergraduate thesis on the epic Ramayana: Michael Sells and Steven Hopkins. Dr. Sells introduced me to Wendy Doniger’s work, and like so many others, I went to the University of Chicago Divinity School to study with her, and her warmth compensated for the Chicago cold. -

“I Cannot Live Without Music”

INTERVIEW “I cannot live without music” Swati Tirunal was undoubtedly one of the most important modern composers, one who included Hindustani styles in his compositions. Nowadays it has become fashionable to say you must avoid Hindustani in Carnatic music or the other way around. But looking back, Bhimsen Joshi was among those south Indians who became luminaries in the north Indian style. How many south Indians are really open to Hindustani music is debatable. The late M.S. Gopalakrishnan was very competent in the Hindustani field, and my colleague Sanjay Subrahmanyan is a Carnatic musician open to Hindustani ragas – he sings a Rama Varma at the Swarasadhana workshop focussing on Swati Tirunal’s compositions pallavi in Bagesree, for instance. Then again there are ‘fundamentalist’ groups Well known Carnatic vocalist Rama Varma was in Chennai recently to who think Behag, Sindhubhairavi, conduct a two-day workshop (9 and 10 February 2013) Swarasadhana, Yamunakalyani, Sivaranjani and their at the Satyananda Yoga Centre at Triplicane. Here he speaks of the event, ilk should be totally done away with. his journey in classical music and his thoughts on the changing trends of the art form. Rama Varma How did Swarasadhana happen? in conversation with I have been teaching in a village called Perla near Mangalore for the past M. Ramakrishnan four years, at a music school called Veenavadini, run by the musician Yogeesh Sharma. He invites musicians to visit there once a year. Four years ago Veenavadini invited me. They enjoyed my teaching and Do you follow the same style of teaching I enjoyed being there too, and my visits became regular. -

Rukmini Devi Arundale

Rukmini Devi Arundale January 6, 2021 Rukmini Devi Arundale(1904 – 1986) “I was very intuitive from an early age. I responded to people just as I responded to art – through an inner feeling which is difficult to explain. I just felt some things were right and some were not…” Rukmini Devi was born on 29 February 1904 in Madurai of Tamilnadu. She was the first woman in Indian history to be nominated a member of the Rajya Sabha. Rukmini Devi Arundale was an Indian theosophist, dancer, and choreographer of the Indian classical dance form of Bharatnatyam, and an activist for Animal welfare. The most important revivalist of Bharatanatyam from its original ‘sadhir’ style prevalent amongst the temple dancers, the Devadasis, she also worked for the re- establishment of traditional Indian arts and crafts. She was awarded the Padma Bhushan in 1956 and the Sangeet Natak Akademi Fellowship in 1967. In January 1936, she along with her husband established Kalakshetra, an academy of dance and music, built around the ancient Indian Gurukul system, at Adyar, at Chennai. Today the academy is a deemed university under the Kalakshetra Foundation. She also became very close to Annie Besant and helped her with her work. She went on to become the President of the Theosophical Society after Dr. Besant’s passing and Rukmini Devi herself was an active member of the Theosophical movement. She gave her first performance at the Diamond Jubilee celebrations of the Theosophical Society in 1935. Theosophists hailed her as the World Mother, to her family in Kalakshetra she is Athai (paternal aunt). -

Sadir, Bharatanatyam, Feminist Theory Sriv1dya

ANOTHER STAGE IN THE LIFE OP THE NATION: SADIR, BHARATANATYAM, FEMINIST THEORY A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF HYDERABAD FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES SRIV1DYA NATARAJAN FEBRUARY, 1997 CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Ms. Srividya Natarajan worked under my supervision for the Ph.D. Degree in English. Her thesis entitled "Another Stage in the Life of the Nation: Sadir. Bharatanatyam. Feminist Theory" represents her own independent work at the University of Hyderabad. This work has not been submitted to any other institution for the award of any degree. Hyderabad Tejaswini Niranjana Date: 14-02-1997 Department of English School of Humanities University of Hyderabad Hyderabad February 12, 1997 This is to certify that I, Srividya Natarajan, have carried out the research embodied in the present thesis for the full period prescribed under Ph.D. ordinances of the University. I declare to the best of my knowledge that no part of this thesis was earlier submitted for the award of research degree of any University. To those special teachers from whose lives I have learnt more than from all my other education put together: Kittappa Vadhyar, Paati, Thatha, Paddu, Mythili, Nigel. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the course of five years of work on this thesis, I have piled up more debts than I can acknowledge in due measure. A fellowship from the University Grants Commission gave me leisure for full-time research; some of this time was spent among the stacks of the Tamil Nadu Archives, the Madras University Library, the Music Academy Library, the Adyar Library, the T.T. -

Rolllist Btech DD Bs2020batch

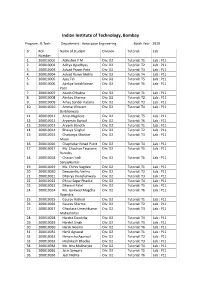

Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay Program : B.Tech. Department : Aerospace Engineering Batch Year : 2020 Sr. Roll Name of Student Division Tutorial Lab Number 1. 200010001 Abhishek P M Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 2. 200010002 Aditya Upadhyay Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 3. 200010003 Advait Pravin Pote Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 4. 200010004 Advait Ranvir Mehla Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 5. 200010005 Ajay Tak Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 6. 200010006 Ajinkya Satishkumar Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Patil 7. 200010007 Akash Chhabra Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 8. 200010008 Akshay Sharma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 9. 200010009 Amay Sunder Kataria Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 10. 200010010 Ammar Khozem Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 Barbhaiwala 11. 200010011 Anup Nagdeve Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 12. 200010012 Aryaman Bansal Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 13. 200010013 Aryank Banoth Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 14. 200010014 Bhavya Singhal Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 15. 200010015 Chaitanya Shankar Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 Moon 16. 200010016 Chaphekar Ninad Punit Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 17. 200010017 Ms. Chauhan Tejaswini Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 Ramdas 18. 200010018 Chavan Yash Div: D2 Tutorial: T6 Lab : P11 Sanjaykumar 19. 200010019 Ms. Chinni Vagdevi Div: D2 Tutorial: T1 Lab : P11 20. 200010020 Deepanshu Verma Div: D2 Tutorial: T2 Lab : P11 21. 200010021 Dhairya Jhunjhunwala Div: D2 Tutorial: T3 Lab : P11 22. 200010022 Dhruv Sagar Phadke Div: D2 Tutorial: T4 Lab : P11 23. 200010023 Dhwanil Patel Div: D2 Tutorial: T5 Lab : P11 24. -

Mechanical Aspire

Newsletter Volume 6, Issue 11, November 2016 Mechanical Aspire Achievements in Sports, Projects, Industry, Research and Education All About Nobel Prize- Part 35 The Breakthrough Prize Inspired by Nobel Prize, there have been many other prizes similar to that, both in amount and in purpose. One such prize is the Breakthrough Prize. The Breakthrough Prize is backed by Facebook chief executive Mark Zuckerberg and Google co-founder Sergey Brin, among others. The Breakthrough Prize was founded by Brin and Anne Wojcicki, who runs genetic testing firm 23andMe, Chinese businessman Jack Ma, and Russian entrepreneur Yuri Milner and his wife Julia. The Breakthrough Prizes honor important, primarily recent, achievements in the categories of Fundamental Physics, Life Sciences and Mathematics . The prizes were founded in 2012 by Sergey Brin and Anne Wojcicki, Mark Zuckerberg and Priscilla Chan, Yuri and Julia Milner, and Jack Ma and Cathy Zhang. Committees of previous laureates choose the winners from candidates nominated in a process that’s online and open to the public. Laureates receive $3 million each in prize money. They attend a televised award ceremony designed to celebrate their achievements and inspire the next generation of scientists. As part of the ceremony schedule, they also engage in a program of lectures and discussions. Those that go on to make fresh discoveries remain eligible for future Breakthrough Prizes. The Trophy The Breakthrough Prize trophy was created by Olafur Eliasson. “The whole idea for me started out with, ‘Where do these great ideas come from? What type of intuition started the trajectory that eventually becomes what we celebrate today?’” Like much of Eliasson's work, the sculpture explores the common ground between art and science. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90b9h1rs Author Sriram, Pallavi Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Pallavi Sriram 2017 Copyright by Pallavi Sriram 2017 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Performative Geographies: Trans-Local Mobilities and Spatial Politics of Dance Across & Beyond the Early Modern Coromandel by Pallavi Sriram Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Janet M. O’Shea, Chair This dissertation presents a critical examination of dance and multiple movements across the Coromandel in a pivotal period: the long eighteenth century. On the eve of British colonialism, this period was one of profound political and economic shifts; new princely states and ruling elite defined themselves in the wake of Mughal expansion and decline, weakening Nayak states in the south, the emergence of several European trading companies as political stakeholders and a series of fiscal crises. In the midst of this rapidly changing landscape, new performance paradigms emerged defined by hybrid repertoires, focus on structure and contingent relationships to space and place – giving rise to what we understand today as classical south Indian dance. Far from stable or isolated tradition fixed in space and place, I argue that dance as choreographic ii practice, theorization and representation were central to the negotiation of changing geopolitics, urban milieus and individual mobility. -

Brahmanical Patriarchy and Voices from Below: Ambedkar's Characterization of Women's Emancipation

Open Political Science, 2020; 3: 175–182 Research Article Harsha Senanayake*, Samarth Trigunayat Brahmanical Patriarchy and Voices from Below: Ambedkar‘s Characterization of Women’s Emancipation https://doi.org/10.1515/openps-2020-0014 received May 8, 2020; accepted June 2, 2020. Abstract: Western feminism created a revolution on the international stage urging the world to look at things through the perspective of women who were historically suppressed because of their gender, yet in many instances, it failed to address the issue of women in the Indian subcontinent because of the existence of social hierarchies that are alien concepts to the western world. As a result, the impact of western feminist thinkers was limited to only the elites in the Indian subcontinent. The idea of social hierarchy is infamously unique to the South Asian context and hence, in the view of the authors, this evil has to be fought through homegrown approaches which have to address these double disadvantages that women suffer in this part of the world. While many have tried to characterize Ambedkar’s political and social philosophy into one of the ideological labels, his philosophy was essentially ‘a persistent attempt to think things through’. It becomes important here to understand what made Ambedkar different from others; what was his social condition and his status in a hierarchal Hindu Society. As a matter of his epistemology, his research and contribution did not merely stem from any particular compartmentalized consideration of politics or society, rather it encompassed the contemporary socio-political reality taking into consideration other intersectionalities like gender and caste. -

1St Part Annual Report 22.6.2015...Cdr

t RAMAKRISHNA MISSION t STUDENTS' HOME MYLAPORE, CHENNAI-600 004 (A Branch of the Ramakrishna Mission with its Headquarters at Belur Math (P.O.) Dist. Howrah (W.B.) - 711 202) Established : 17th February, 1905 Affiliated : 1918 ONE HUNDRED AND TENTH ANNUAL REPORT 01-04-2014 to 31-03-2015 Issued by The Secretary, RAMAKRISHNA MISSION STUDENTS’ HOME # 66, P.S. Sivasami Salai, Mylapore, Chennai - 600 004. Phone : 2499 0264 / 4210 7550 Fax : 044 - 4231 2830. E-mail : [email protected] web : www.rkmshome.org t t CONTENTS Subject Page No. Managing Committee Inside Front Cover Ramakrishna Math & Mission 3 Ramakrishna Mission Students' Home 4 Care of Inmates under 6 Gurukula System of Education Special Activities 12 Chapters of Old Boys' Association 15 Honorary Workers 16 Ramakrishna Mission Polytechnic College (Residential) 20 Ramakrishna Mission Residential High School Collegiate Section 31 Ramakrishna Centenary Primary School 37 We fondly remember 47 Appendix –“A” List of Donors 2014-15 49 (General Donation, Special Donation for Deepavali, Annadhanam, Akshaya Tritiya, Home Day & students educational assistance etc) (i) From Old Students of the Home (ii) From Friends and Well-wishers Appendix – “B” Endowments 68 Endowments donations received during 2014-15 (i) From Old Students of the Home (ii) From Friends and Well-wishers 2 Appendix – “C” 78 Sponsorship Donations under section 35AC for 2 new technical courses (i) From Old Students of the Home (ii) Friends & Well - Wishers Appendix – “D” 95 (i) Donations for acquiring Moveable Property (80G) -

WOODWIND INSTRUMENT 2,151,337 a 3/1939 Selmer 2,501,388 a * 3/1950 Holland

United States Patent This PDF file contains a digital copy of a United States patent that relates to the Native American Flute. It is part of a collection of Native American Flute resources available at the web site http://www.Flutopedia.com/. As part of the Flutopedia effort, extensive metadata information has been encoded into this file (see File/Properties for title, author, citation, right management, etc.). You can use text search on this document, based on the OCR facility in Adobe Acrobat 9 Pro. Also, all fonts have been embedded, so this file should display identically on various systems. Based on our best efforts, we believe that providing this material from Flutopedia.com to users in the United States does not violate any legal rights. However, please do not assume that it is legal to use this material outside the United States or for any use other than for your own personal use for research and self-enrichment. Also, we cannot offer guidance as to whether any specific use of any particular material is allowed. If you have any questions about this document or issues with its distribution, please visit http://www.Flutopedia.com/, which has information on how to contact us. Contributing Source: United States Patent and Trademark Office - http://www.uspto.gov/ Digitizing Sponsor: Patent Fetcher - http://www.PatentFetcher.com/ Digitized by: Stroke of Color, Inc. Document downloaded: December 5, 2009 Updated: May 31, 2010 by Clint Goss [[email protected]] 111111 1111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111111 US007563970B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 7,563,970 B2 Laukat et al. -

Some Questions Concerning the Ugc Course in Astrology

SOME QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE UGC COURSE IN ASTROLOGY Kushal Siddhanta 18 AUGUST 2001. Dr. Murali Manohar cient Indian astronomer Varahamihira who Joshi, the present Union HRD Minister and in the sixth century AD spoke about the a former professor of physics in the Alla- earth's rotation.” Citing another fact in sup- habad University, was invited to the IIT, port of introducing astrology as a university Kharagpur, as the chief guest at an open- course, he said, 16 universities of the coun- ing function organized on the occasion of try had already been offering astrology as its fiftieth foundation anniversary. The a subject in various forms. So his govern- West Bengal Chief Minister Mr. Buddhadeb ment is doing nothing new. People should Bhattacharya was another guest. not oppose the astrology and other courses only on political reasons. There may be de- As expected, Mr. Bhattacharya in his bates and arguments over the issue. The speech indirectly criticized the policy of the Government, he assured all, was ready to Union Government to introduce worn out hear. So on and so forth. subjects like astrology, paurohitya, vas- tushastra, yoga and human consciousness, It all had started when the UGC issued a etc., in the universities through the Univer- circular on 23 February 2001 with a pro- sity Grant Commission (UGC). Dr. Joshi posal to all the universities of the country in his address, however, did not go into to introduce UG and PG courses as well the trouble of explaining why his depart- as doctoral researches in Vedic Astrology ment was so keen on funding these anti- which it later renamed in parenthesis as quated subjects in the universities in spite Jyotirvigyan (astronomy).