PDF Du Chapitre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monographie Regionale Beni Mellal-Khenifra 2017

Royaume du Maroc المملكة المغربية Haut-Commissariat au المندوبية السامية للتخطيط Plan MONOGRAPHIE REGIONALE BENI MELLAL-KHENIFRA 2017 Direction régionale Béni Mellal-Khénifra Table des matières INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................ 8 PRINCIPAUX TRAITS DE LA REGION BENI MELLAL- KHENIFRA ................. 10 CHAPITRE I : MILIEU NATUREL ET DECOUPAGE ADMINISTRATIF ............ 15 1. MILIEU NATUREL ................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Reliefs ....................................................................................................................... 16 1.2. Climat ....................................................................................................................... 18 2. Découpage administratif ............................................................................................ 19 CHAPITRE II : CARACTERISTIQUES DEMOGRAPHIQUES DE LA POPULATION ........................................................................................................................ 22 1. Population ................................................................................................................... 23 1.1. Evolution et répartition spatiale de la population .................................................. 23 1.2. Densité de la population .......................................................................................... 26 1.3. Urbanisation ........................................................................................................... -

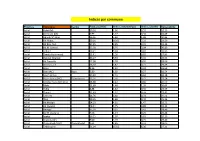

Indices Par Commune

Indices par commune Province Commune Centre Taux_pauvreté indice_volumétrique indice_séverité Vulnérabilité Azilal Azilal (M) 10,26 1,96 0,55 19,23 Azilal Demnate (M) 6,99 1,27 0,34 16,09 Azilal Agoudi N'Lkhair 26,36 5,84 1,88 30,84 Azilal Ait Abbas 50,01 16,62 7,33 23,59 Azilal Ait Bou Oulli 37,95 9,65 3,45 31,35 Azilal Ait M'Hamed 35,58 8,76 3,04 30,80 Azilal Tabant 19,21 3,24 0,81 33,95 Azilal Tamda Noumercid 15,41 2,90 0,82 27,83 Azilal Zaouiat Ahansal 35,27 9,33 3,45 28,53 Azilal Ait Taguella 17,08 3,28 0,95 28,09 Azilal Bni Hassane 16,10 2,87 0,77 29,55 Azilal Bzou 8,56 1,32 0,32 24,68 Azilal Bzou (AC) Bzou 5,80 1,02 0,27 16,54 Azilal Foum Jemaa 15,22 2,51 0,62 31,18 Azilal Foum Jemaa (AC) Foum Jemaa 13,26 2,56 0,72 22,54 Azilal Moulay Aissa Ben Driss 13,38 2,42 0,66 26,59 Azilal Rfala 21,69 4,46 1,35 30,64 Azilal Tabia 8,88 1,42 0,35 23,59 Azilal Tanant 11,63 2,12 0,59 23,41 Azilal Taounza 13,76 2,60 0,74 25,52 Azilal Tisqi 10,35 1,66 0,40 25,26 Azilal Ait Mazigh 24,23 4,91 1,47 33,72 Azilal Ait Ouqabli 18,31 3,25 0,88 33,12 Azilal Anergui 35,18 9,25 3,41 28,49 Azilal Bin El Ouidane 7,96 1,14 0,25 25,44 Azilal Isseksi 16,21 2,97 0,81 29,19 Azilal Ouaouizeght 9,00 1,19 0,25 29,46 Azilal Ouaouizeght (AC) Ouaouizeght 9,61 1,85 0,52 18,05 Azilal Tabaroucht 51,04 15,52 6,36 27,11 Province Commune Centre Taux_pauvreté indice_volumétrique indice_séverité Vulnérabilité Azilal Tagleft 27,66 6,89 2,44 26,89 Azilal Tiffert N'Ait Hamza 16,84 3,99 1,37 21,90 Azilal Tilougguite 24,10 5,32 1,70 30,13 Azilal Afourar 5,73 0,80 0,17 20,51 Azilal -

Cadastre Des Autorisations TPV Page 1 De

Cadastre des autorisations TPV N° N° DATE DE ORIGINE BENEFICIAIRE AUTORISATIO CATEGORIE SERIE ITINERAIRE POINT DEPART POINT DESTINATION DOSSIER SEANCE CT D'AGREMENT N Casablanca - Beni Mellal et retour par Ben Ahmed - Kouribga - Oued Les Héritiers de feu FATHI Mohamed et FATHI Casablanca Beni Mellal 1 V 161 27/04/2006 Transaction 2 A Zem - Boujad Kasbah Tadla Rabia Boujad Casablanca Lundi : Boujaad - Casablanca 1- Oujda - Ahfir - Berkane - Saf Saf - Mellilia Mellilia 2- Oujda - Les Mines de Sidi Sidi Boubker 13 V Les Héritiers de feu MOUMEN Hadj Hmida 902 18/09/2003 Succession 2 A Oujda Boubker Saidia 3- Oujda La plage de Saidia Nador 4- Oujda - Nador 19 V MM. EL IDRISSI Omar et Driss 868 06/07/2005 Transaction 2 et 3 B Casablanca - Souks Casablanca 23 V M. EL HADAD Brahim Ben Mohamed 517 03/07/1974 Succession 2 et 3 A Safi - Souks Safi Mme. Khaddouj Bent Salah 2/24, SALEK Mina 26 V 8/24, et SALEK Jamal Eddine 2/24, EL 55 08/06/1983 Transaction 2 A Casablanca - Settat Casablanca Settat MOUTTAKI Bouchaib et Mustapha 12/24 29 V MM. Les Héritiers de feu EL KAICH Abdelkrim 173 16/02/1988 Succession 3 A Casablanca - Souks Casablanca Fès - Meknès Meknès - Mernissa Meknès - Ghafsai Aouicha Bent Mohamed - LAMBRABET née Fès 30 V 219 27/07/1995 Attribution 2 A Meknès - Sefrou Meknès LABBACI Fatiha et LABBACI Yamina Meknès Meknès - Taza Meknès - Tétouan Meknès - Oujda 31 V M. EL HILALI Abdelahak Ben Mohamed 136 19/09/1972 Attribution A Casablanca - Souks Casablanca 31 V M. -

Chapitre VI La Ville Et Ses Équipements Collectifs

Chapitre VI La ville et ses équipements collectifs Introduction L'intérêt accordé à la connaissance du milieu urbain et de ses équipements collectifs suscite un intérêt croissant, en raison de l’urbanisation accélérée que connaît le pays, et de son effet sur les équipements et les dysfonctionnements liés à la répartition des infrastructures. Pour résorber ce déséquilibre et assurer la satisfaction des besoins, le développement d'un réseau d'équipements collectifs appropriés s'impose. Tant que ce déséquilibre persiste, le problème de la marginalisation sociale, qui s’intensifie avec le chômage et la pauvreté va continuer à se poser La politique des équipements collectifs doit donc occuper une place centrale dans la stratégie de développement, particulièrement dans le cadre de l’aménagement du territoire. La distribution spatiale de la population et par conséquent des activités économiques, est certes liée aux conditions naturelles, difficiles à modifier. Néanmoins, l'aménagement de l'espace par le biais d'une politique active peut constituer un outil efficace pour mettre en place des conditions favorables à la réduction des disparités. Cette politique requiert des informations fiables à un niveau fin sur l'espace à aménager. La présente étude se réfère à la Base de données communales en milieu urbain (BA.DO.C) de 1997, élaborée par la Direction de la Statistique et concerne le niveau géographique le plus fin à savoir les communes urbaines, qui constituent l'élément de base de la décentralisation et le cadre d'application de la démocratie locale. Au recensement de 1982, était considéré comme espace urbain toute agglomération ayant un minimum de 1 500 habitants et qui présentait au moins quatre des sept conditions énumérées en infra1. -

Monographie De La Province De Khouribga

ROYAUME DU MAROC HAUT COMMISSARIAT AU PLAN DIRECTION REGIONALE BENI MELLAL – KHENIFRA Siège de la Province Kouribga MONOGRAPHIE DE LA PROVINCE DE KHOURIBGA Avril 2017 1 SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION 4 I-PRESENTATION DE LA PROVINCE 5 1. Localisation géographique 6 2. Climat 6 3. Relief 6 4. Découpage communal et administratif 7 II- ASPECTS DEMOGRAPHIQUES ET 9 SOCIAUX-ECONOMIQUES DE LA POPULATION 1. Evolution de la population 10 2. Répartition de la population par sexe et âge 12 3. Etat matrimonial 14 4. L'âge au 1er mariage 16 5. Fécondité 17 6. Les caractéristiques de l'éducation 18 6.1. Analphabétisme 18 6.2. Scolarisation des enfants âgés de 7 à 12 ans 19 6.3. Niveau d’instruction de la population non scolarisée 20 6.4. Langues lues et écrites 20 7. Activité et chômage 21 7.1. Population active et taux d’activité net 21 7.2. Population active selon la situation dans la profession 22 7.3. Taux de chômage 22 III. MENAGES ET CONDITIONS D'HABITATION 24 DES MENAGES 1. Evolution du nombre de ménages 2004-2014 dans la province 25 2. Conditions d’habitation des ménages 25 2.1. Conditions d’habitation des ménages en milieu urbain 25 2.2. Conditions d’habitation des ménages en milieu rural 26 IV. SECTEURS SOCIAUX 30 1. Education nationale 31 2. Santé 35 3. Justice 38 4. Activités culturelles et loisirs 39 5. Entraide nationale 40 2 V. SECTEURS PRODUCTIFS 41 1. Agriculture et forêts 42 1.1. Agriculture 42 1.2. Elevage 44 1.2. Forêts 45 2. -

Télécharger Le Document

CARTOGRAPHIE DU DÉVELOPPEMENT LOCAL MULTIDIMENSIONNEL NIVEAU ET DÉFICITS www.ondh.ma SOMMAIRE Résumé 6 Présentation 7 1. Approche méthodologique 8 1.1. Portée et lecture de l’IDLM 8 1.2. Fiabilité de l’IDLM 9 2. Développement, niveaux et sources de déficit 10 2.1. Cartographie du développement régional 11 2.2. Cartographie du développement provincial 13 2.3. Développement communal, état de lieux et disparité 16 3. L’IDLM, un outil de ciblage des programmes sociaux 19 3.1 Causes du déficit en développement, l’éducation et le niveau de vie en tête 20 3.2. Profil des communes à développement local faible 24 Conclusion 26 Annexes 27 Annexe 1 : Fiabilité de l’indice de développement local multidimensionnel (IDLM) 29 Annexe 2 : Consistance et méthode de calcul de l’indice de développement local 30 multidimensionnel Annexe 3 : Cartographie des niveaux de développement local 35 Annexes Communal 38 Cartographie du développement communal-2014 41 5 RÉSUMÉ La résorption ciblée des déficits socio-économiques à l’échelle locale (province et commune) requiert, à l’instar de l’intégration et la cohésion des territoires, le recours à une cartographie du développement au sens multidimensionnel du terme, conjuguée à celle des causes structurelles de son éventuel retard. Cette étude livre à cet effet une cartographie communale du développement et de ses sources assimilées à l’éducation, la santé, le niveau de vie, l’activité économique, l’habitat et les services sociaux, à partir de la base de données «Indicateurs du RGPH 2014» (HCP, 2017). Cette cartographie du développement et de ses dimensions montre clairement que : - La pauvreté matérielle voire monétaire est certes associée au développement humain, mais elle ne permet pas, à elle seule, d’identifier les communes sous l’emprise d’autres facettes de pauvreté. -

MPLS VPN Service

MPLS VPN Service PCCW Global’s MPLS VPN Service provides reliable and secure access to your network from anywhere in the world. This technology-independent solution enables you to handle a multitude of tasks ranging from mission-critical Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP), Customer Relationship Management (CRM), quality videoconferencing and Voice-over-IP (VoIP) to convenient email and web-based applications while addressing traditional network problems relating to speed, scalability, Quality of Service (QoS) management and traffic engineering. MPLS VPN enables routers to tag and forward incoming packets based on their class of service specification and allows you to run voice communications, video, and IT applications separately via a single connection and create faster and smoother pathways by simplifying traffic flow. Independent of other VPNs, your network enjoys a level of security equivalent to that provided by frame relay and ATM. Network diagram Database Customer Portal 24/7 online customer portal CE Router Voice Voice Regional LAN Headquarters Headquarters Data LAN Data LAN Country A LAN Country B PE CE Customer Router Service Portal PE Router Router • Router report IPSec • Traffic report Backup • QoS report PCCW Global • Application report MPLS Core Network Internet IPSec MPLS Gateway Partner Network PE Router CE Remote Router Site Access PE Router Voice CE Voice LAN Router Branch Office CE Data Branch Router Office LAN Country D Data LAN Country C Key benefits to your business n A fully-scalable solution requiring minimal investment -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 49332 - MA PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A PROPOSED LOAN Public Disclosure Authorized IN THE AMOUNT OF EUROS 25.9 MILLION AND US$8.6 MILLION (US$43 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE OFFICE NATIONAL DE L’EAU POTABLE (ONEP) (NATIONAL POTABLE WATER AUTHORITY) WITH THE GUARANTEE OF THE Public Disclosure Authorized KINGDOM OF MOROCCO FOR THE OUM ER RBIA SANITATION PROJECT May 20, 2010 Sustainable Development Department Middle East and North Africa Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective March 28, 2010) Currency Unit = Moroccan Dirham (MAD) MAD 8.312 = US$ 1 US$ 0.120 = MAD 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 – December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS BOD Biological Oxygen Demand CAS Country Assistance Strategy CDM Clean Development Mechanism CPS Country Partnership Strategy CR Rural Municipality/Commune Rurale DAE Department for Sanitation and Environment (ONEP)/Direction de l’Assainissement et de l’Environnement DAM Department for Procurement (ONEP)/ Direction Approvisionnement et Marchés DPL Development Policy Loan EA Environmental Assessment EMP Environmental Management Plan ESW Economic and Sector Work GEP Program for Access to Potable Water/Programme de Généralisation de l’Eau Potable GOM Government of Morocco HC House Connection -

La Région De Béni Mellal-Khénifra

ROYAUME DU MAROC Ministère de l’Intérieur La région de Béni Mellal-Khénifra MONOGRAPHIE GENERALE 2015 SOMMAIRE I. PREAMBULE .................................................................................................................................................. 1 II. PRESENTATION GENERALE DE L'ESPACE REGIONAL ....................................................................................... 2 1. CADRE ADMINISTRATIF ........................................................................................................................................... 2 2. CADRE GEOGRAPHIQUE GENERAL .............................................................................................................................. 6 III. CONDITIONS ET RESSOURCES NATURELLES ................................................................................................... 8 1. CLIMAT ET PRECIPITATIONS ..................................................................................................................................... 8 2. RESSOURCES HYDROGRAPHIQUES ........................................................................................................................... 10 a) Ressources en eaux superficielles .............................................................................................................. 10 b) Eaux souterraines ...................................................................................................................................... 10 3. LES RESSOURCES FORESTIERES ............................................................................................................................... -

World Bank Document

PROJECT INFORMATION DOCUMENT (PID) APPRAISAL STAGE Report No.: AB5283 Project Name Morocco Oum Er Rbia Sanitation Region MIDDLE EAST AND NORTH AFRICA Public Disclosure Authorized Sector Sanitation (100%); Project ID P098459 Borrower(s) OFFICE NATIONAL DE L'EAU POTABLE (ONEP) Implementing Agency ONEP – Morocco Office National de l'Eau Potable (ONEP) Station de Traitement Akrach Route des Zaers,-Akrach Rabat Morocco Tel: (212-537) 650-695 Fax: (212-537) 726-707 Environment Category [X] A [ ] B [ ] C [ ] FI [ ] TBD (to be determined) Public Disclosure Authorized Date PID Prepared March 8, 2010 Date of Appraisal March 30, 2010 Authorization Date of Board Approval May 27, 2010 A. Country and Sector Background 1. With 700m3/capita/yr, of which 70 percent of withdrawals are from surface water and 30 percent from groundwater, Morocco has the highest water potential in the Maghreb. However, the water is unevenly distributed between different parts of the country and highly variable within and between years. Droughts are common. Ninety percent of economically accessible surface resources are already dammed, leaving few options for additional surface water storage. Public Disclosure Authorized Population and economic growth have increased demand even as supply has fallen. The country has seen a 30 percent drop in average precipitation since 1970, increasingly accepted as a sign of climate change. In recent years, the amount of surface water stored in dams has repeatedly fallen short of the amount expected. As a result, severe restrictions for irrigation water have been common. Wherever they can, farmers have been partially making up the shortfall in surface water by tapping into groundwater, and aquifer depletion is becoming more and more serious. -

Situation Des Créances De La Direction Régionale De Béni Mellal À La Date De Référence Du 24/05/2013

Situation des créances de la Direction Régionale de Béni Mellal à la date de référence du 24/05/2013 Page 1 sur 30 Introduction Dans le cadre d’une politique orientée vers l’amélioration de la trésorerie de l’Office à travers le recouvrement des créances, le tableau de bord hebdomadaire a été rédigé selon ce nouveau modèle afin de mettre en évidence les chiffres reflétant davantage la situation des créances de la Direction Régionale Distribution de Béni Mellal. Ainsi, les créances de la DRB seront regroupées selon trois volets : Créances migrées à SAP comme PNS qui sont arrêtés au mois 03/2007 qui est la date de début de migration et qu’on notera créances migrées ; Les créances facturées entre le mois 04/2007 et 2011 dans SAP auxquelles les factures sont toujours disponibles dans le système ; Créances de l’année 2012. 1 État des règlements du 18.05.2013 au 24.05.2013 Classe de Dépôt de Frais de Autre Energie Travaux PERG Intérêts Acompt Timbre compte garantit relance règlemts Administration s 714 964,77 31 475,92 1 763,00 1 124,24 0,00 0,00 0,00 93,82 0,00 Clients occasionnels Clts Multi- Contrats 7761,79 13459,36 0 118,41 0 1207,65 0 3,02 0 Collectivités locales 2725497,63 30200,77 7353 86,01 0 0 225 6,78 179019,28 Les agents ONE 0,00 555,23 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 1,39 0,00 Offices 100 566,97 0,00 0,00 104,19 0,00 0,00 0,00 16,02 0,00 2 035 114 3 Particuliers 8 801 647,14 436,10 527,27 29 064,91 395,43 146 323,11 7 135,83 20 591,24 1 860,50 Stés nationales 1 140 371,50 53 467,74 0,00 1 107,27 0,00 308,89 0,00 0,00 0,00 13 490 2 164 123 31 3 20 180 147 839,65 7 360,83 Total général 809,80 595,12 643,27 605,03 395,43 712,27 879,78 Le montant des règlements réalisés à la DRB au cours de la période du 18.05.2013 au 24.05.2013 a atteint 16 170 841,18 DH dont 13 490 809,80 DH en factures énergie. -

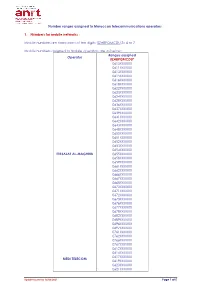

Number Ranges Assigned to Moroccan Telecommunications Operators

Number ranges assigned to Moroccan telecommunications operators 1. Numbers for mobile networks : Mobile numbers are composed of ten digits: 0ZABPQMCDU Z= 6 or 7. Mobile numbers assigned to mobile operators are as below: Ranges assigned Operator 0ZABPQMCDU* 0610XXXXXX 0611XXXXXX 0613XXXXXX 0615XXXXXX 0616XXXXXX 0618XXXXXX 0622XXXXXX 0623XXXXXX 0624XXXXXX 0628XXXXXX 0636XXXXXX 0637XXXXXX 0639XXXXXX 0641XXXXXX 0642XXXXXX 0643XXXXXX 0648XXXXXX 0650XXXXXX 0651XXXXXX 0652XXXXXX 0653XXXXXX 0654XXXXXX ITISSALAT AL-MAGHRIB 0655XXXXXX 0658XXXXXX 0659XXXXXX 0661XXXXXX 0662XXXXXX 0666XXXXXX 0667XXXXXX 0668XXXXXX 0670XXXXXX 0671XXXXXX 0672XXXXXX 0673XXXXXX 0676XXXXXX 0677XXXXXX 0678XXXXXX 0682XXXXXX 0689XXXXXX 0696XXXXXX 0697XXXXXX 0761XXXXXX 0762XXXXXX 0766XXXXXX 0767XXXXXX 0612XXXXXX 0614XXXXXX 0617XXXXXX MEDI TELECOM 0619XXXXXX 0620XXXXXX 0621XXXXXX Update issued on 14/06/2021 Page 1 of 5 0625XXXXXX 0631XXXXXX 0632XXXXXX 0644XXXXXX 0645XXXXXX 0649XXXXXX 0656XXXXXX 0657XXXXXX 0660XXXXXX 0663XXXXXX 0664XXXXXX 0665XXXXXX 0669XXXXXX 0674XXXXXX 0675XXXXXX 0679XXXXXX 0684XXXXXX 0688XXXXXX 0691XXXXXX 0693XXXXXX 0694XXXXXX 0770XXXXXX 0771XXXXXX 0772XXXXXX 0773XXXXXX 0774XXXXXX 0775XXXXXX 0777XXXXXX 0526XXXXXX 0527XXXXXX 0533XXXXXX 0534XXXXXX 0540XXXXXX 0546XXXXXX 0547XXXXXX 0550XXXXXX 0553XXXXXX 060XXXXXXX 0626XXXXXX 0627XXXXXX 0629XXXXXX 0630XXXXXX 0633XXXXXX 0634XXXXXX Wana Corporate 0635XXXXXX 0638XXXXXX 0640XXXXXX 0646XXXXXX 0647XXXXXX 0680XXXXXX 0681XXXXXX 0687XXXXXX 0690XXXXXX 0695XXXXXX 0698XXXXXX 0699XXXXXX 0700XXXXXX 0701XXXXXX 0702XXXXXX 0703XXXXXX