Bulletin Spring 2014 Corrected 0.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curveball: the Remarkable Story of Toni Stone, the First Woman to Play Professional Baseball in the Negro League Online

vgoxR (Read ebook) Curveball: The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone, the First Woman to Play Professional Baseball in the Negro League Online [vgoxR.ebook] Curveball: The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone, the First Woman to Play Professional Baseball in the Negro League Pdf Free Martha Ackmann ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1505887 in Books 2017-02-01Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 9.00 x .70 x 6.00l, 1.20 #File Name: 1613736568288 pages | File size: 38.Mb Martha Ackmann : Curveball: The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone, the First Woman to Play Professional Baseball in the Negro League before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Curveball: The Remarkable Story of Toni Stone, the First Woman to Play Professional Baseball in the Negro League: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. and recommended for allBy WriterToo little has been written about Toni Stone. This well-written biography covers her entire life, smoothly bringing together anecdotes, interviews, and facts (and you know how baseball loves its facts and stats!). It's a book boys and girls, and the men and women they become, should read to provide a woman's perspective in the early 1950s about traditions and customs, gender roles, "official" rules, barriers of all types, and discrimination. What's changed? What more should change? Appropriate for high school and up, and recommended for all, even non baseball fans.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. ONE HELLUVA PITCHBy Mike StewartI loved CURVEBALL. -

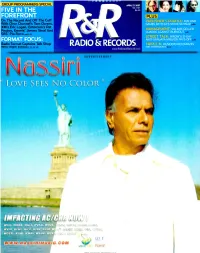

Radio & Records

R MEL .! GROUP PROGRAMMERS SPECIAL APRIL 27, 2007 NO. 1707 $6.50 O _ Off The Cuff PUBLISHER'S PROFILE: FUN AND With Clear Channel's Tom Owens, GAMES WITH EA'S STEVE SCHNUR XM's Eric Logan, Entercom's Pat MANAGEMENT: VALERIE GELLER Paxton, Emmis' Jimmy Steal An GUARDS AGAINST BURNOUT. SBS' Pio Ferro PP.12-21 STREET TALK: WRDW'S 21 -DAY ANTI -SANJAYA MISSION PAYS OFF Radio FIPMAt Captaillinnik Shop RADIO & RECORDS TRIPLE A: MUSEXPO RECOGNIZES With R &R Editors pp.22 -58 NIC HARCOURT www.RadioandRecords.com ADVERTISEMEÑT WCIL, WXXX, WGLI, WVAQ, WRZE, t> LU16c, l l .u" 1.0_1:.124, WVIQ, KFMI, WIFC, KISR, KQID, L4.21.4+. L'tA -(ú.6ti. WGER, KVKI, KWAV, WAHR, WJX = 1_titiLL, L't!R (_.L ' LEp:E WORLD Namiri www.americanradiohistory.com Leading Off Today's Program: The Incentives. PRESENTING LOUISIANA'S SOUND RECORDING INVESTOR TAX CREDIT. If you're looking to make some noise in the entertainment industry, Louisiana Economic Development invites you to experience the Sound Recording Investor Tzx Credit. It reimburses 10 -20 percent of your investment in scud recording, production, recording studios and infrastru:ture projects. Much like our film program. the Sound Recording Tax Credit is designed to boost record production by ncucing your costs. To learn more about this program and othe- incentives. call Sherri McConnell at 225.342.5832. LOUISOMIA ECONOMIC / DEVELOPMENT LouisianaForward.com/Entertainment www.americanradiohistory.com &R CONVENTION 2007 TAKES PLACE SEPTEMBER 26 -28 IN CHARLOTTE, N.C. REGISTER AT WWW.RADIOANDRECORDS.COM NewsroCu MOVER ON THE WEB Reich Place, Reich Time WLTW/New York Tops 2006 Imus Fallout Continues RCA Music Group regional promotion rep Revenue Earners The fallout from the firing of talk host Don Josh Reich is upped to director of top 40 field Clear Channel AC WLTW /NewYork was the nation's highest revcuue- generating radio Imus by CBS Radio continues. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

Amherst College, Emily Dickinson, Person, Poetry, and Place

Narrative Section of a Successful Proposal The attached document contains the narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful proposal may be crafted. Every successful proposal is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the program guidelines at www.neh.gov/grants/education/landmarks-american-history-and- culture-workshops-school-teachers for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Education Programs staff well before a grant deadline. The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Emily Dickinson: Person, Poetry, and Place Institution: Amherst College Project Director: Cynthia Dickinson Grant Program: Landmarks of American History and Culture Workshops 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 302, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8500 F 202.606.8394 E [email protected] www.neh.gov 2014 “Emily Dickinson: Person, Poetry, and Place” 2 The Emily Dickinson Museum proposes to offer a 2014 Landmarks of American History and Culture Workshop for School Teachers, “Emily Dickinson: Person, Poetry and Place.” Unpublished in her lifetime, Emily Dickinson’s poetry is considered among the finest in the English language. Her intriguing biography and the complexity of her poems have fostered personal and intellectual obsessions among readers that are far more pronounced for Dickinson than for any other American poet. -

Nov-Dec 2010

THE EMILY DICKINSON INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY Volume 22, Number 2 November/December 2010 “The Only News I know / Is Bulletins all Day / From Immortality.” The Oxford Conference in Retrospect EMILY DICKINSON INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY Officers President: Martha Ackmann Vice President: Jed Deppman Secretary: Stephanie Tingley Treasurer: James C. Fraser Board Members Martha Ackmann James C. Fraser Nancy Pridgen Antoine Cazé Jonnie Guerra Martha Nell Smith Paul Crumbley Suzanne Juhasz Alexandra Socarides Jed Deppman Marianne Noble Hiroko Uno Cindy Dickinson Elizabeth Petrino Jane Wald (Honorary Board Member) Vivian Pollak (Honorary Board Member) Legal Advisor:Barbara Leukart Nominations Chair:Ellen Louise Hart Membership Chair:Jonnie Legal Advisor:Guerra Barbara Leukart Chapter Development Chair: Nancy Pridgen Dickinson and Nominationsthe Arts Chair:Barbara Chair: JonnieDana Guerra Book Review Editor: Barbara Kelly Chapter Development Membership Chair:Nancy Chair: PridgenElizabeth Petrino Bulletin Editor: Georgiana Strickland Book Dickinson Review Editor:Barbara and the Arts Chair: Kelly Barbara Dana Journal Editor: Cristanne Miller Journal Editor:Cristanne Miller 2010 Sustaining Members Martha Ackmann David H. Forsyth Martha Nell Smith Marilyn Berg-Callander Diana K. Fraser Gary Lee Stonum Jack Capps James C. Fraser Ethan Tarasov Sheila Coghill Marilee Lindemann Robin Tarasov Jane D. Eberwein Cristanne Miller 2010 Contributing Members Paul Beckley Donna Dreyer Niels Kjaer Emily Seelbinder Ellen Beinhorn Robert Eberwein Polly Longsworth Nobuko Shimomura Mary Elizabeth K. Bern- Judith Farr Cindy MacKenzie Maxine Silverman hard Alice Fulton Mayumi Maeda George T. Stone Marisa Bulgheroni Jonnie G. Guerra Daniel Manheim Mason Swilley Diane K. Busker Eleanor Heginbotham Jo Ann Orr Richard Tryon Carolyn L. Cooley Eleanor Humbert Carol Pippen Hiroko Uno Barbara Dana Suzanne Juhasz Vivian R. -

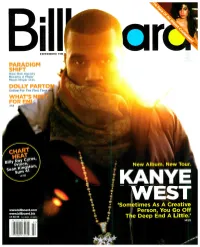

`Sometimes As a Creative

EXPERIENCE THE PARADIGM SHIFT How One Agency Became A Major Music Player >P.25 DOLLY PARTO Online For The First Tim WHAT'S FOR >P.8 New Album. New Tour. KANYE WEST `Sometimes As A Creative www.billboard.com Person, You Go Off www.billboard.biz US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK E5.50 The Deep End A Little.' >P.22 THE YEAR MARK ROHBON VERSION THE CRITICS AIE IAVIN! "HAVING PRODUCED AMY WINEHOUSE AND LILY ALLEN, MARK RONSON IS ON A REAL ROLL IN 2007. FEATURING GUEST VOCALISTS LIKE ALLEN, IN NOUS AND ROBBIE WILLIAMS, THE WHOLE THING PLAYS LIKE THE ULTIMATE HIPSTER PARTY MIXTAPE. BEST OF ALL? `STOP ME,' THE MOST SOULFUL RAVE SINCE GNARLS BARKLEY'S `CRAZY." PEOPLE MAGAZINE "RONSON JOYOUSLY TWISTS POPULAR TUNES BY EVERYONE FROM RA TO COLDPLAY TO BRITNEY SPEARS, AND - WHAT DO YOU KNOW! - IT TURNS OUT TO BE THE MONSTER JAM OF THE SEASON! REGARDLESS OF WHO'S OH THE MIC, VERSION SUCCEEDS. GRADE A" ENT 431,11:1;14I WEEKLY "THE EMERGING RONSON SOUND IS MOTOWN MEETS HIP -HOP MEETS RETRO BRIT -POP. IN BRITAIN, `STOP ME,' THE COVER OF THE SMITHS' `STOP ME IF YOU THINK YOU'VE HEARD THIS ONE BEFORE,' IS # 1 AND THE ALBUM SOARED TO #2! COULD THIS ROCK STAR DJ ACTUALLY BECOME A ROCK STAR ?" NEW YORK TIMES "RONSON UNITES TWO ANTITHETICAL WORLDS - RECENT AND CLASSIC BRITPOP WITH VINTAGE AMERICAN R &B. LILY ALLEN, AMY WINEHOUSE, ROBBIE WILLIAMS COVER KAISER CHIEFS, COLDPLAY, AND THE SMITHS OVER BLARING HORNS, AND ORGANIC BEATS. SHARP ARRANGING SKILLS AND SUITABLY ANGULAR PERFORMANCES! * * * *" SPIN THE SOUNDTRACK TO YOUR SUMMER! THE . -

Nov-Dec 2020

THE EMILY DICKINSON INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY Volume 32, Number 2 November/December 2020 “The Only News I know / Is Bulletins all Day / From Immortality.” Puuseppä, itseoppinut Posant mes pas de Planche en Planche olin – jo aikani J’allais mon lent et prudent chemin höyläni kanssa puuhannut Ma Tête semblait environnee d’ Etoiles kun saapui mestari Et mes pieds baignés d’Océan – mittaamaan työtä: oliko Je ne savais pas si le prochain ammattitaitonne Serait ou non mon dernier pas – riittävä - jos, hän palkkaisi Cela me donnait cette précaire Allure puoliksi kummankin Que d’aucuns nomment l’Expérience – Työkalut kasvot ihmisen sai – höyläpenkkikin todisti toisin: rakentaa osamme temppelit! Me áta – canto mesmo assim Proíbe – meu bandolim – Jag aldrig sett en hed. Toca dentro, de mim – Jag aldrig sett havet – men vet ändå hur ljung ser ut Me mata – e a Alma flutua och vad en bölja är – Cantando ao Paraíso – Зашла купить улыбку – раз – Sou Tua – Всего-то лишь одну – Jag aldrig talat med Gud, Что на щеке, но вскользь у Вас - i himlen aldrig gjort visit – Да только мне к Лицу – men vet lika säkert var den är Ту, без которй нет потерь som om jag ägt biljett – Слаба она сиять – Молю, Сэр, подсчитать – её Смогли бы вы продать? 你知道我看不到你的人生 – Алмазы – на моих перстах! Вам ли не знать, о да! 我须猜测 – Рубины – словно Кровь, горят – 多少次这让我痛苦 – 今天承认 – Топазы – как звезда! Еврею торг такой в пример! 多少次为了我的远大前程 Что скажите мне – Сэр? 那勇敢的双眼悲痛迷蒙 – 但我估摸呀猜测令人伤心 – 我的眼啊 – 已模糊不清! Officers President: Elizabeth Petrino Vice-President: Eliza Richards Secretary: Adeline Chevrier-Bosseau Treasurer: James C. Fraser Board Members Renée Bergland Páraic Finnerty Elizabeth Petrino George Boziwick James C. -

2008-05-12.Pdf

1 2 2 BUZZ 05.12.08 daily.titan daily.titan BUZZ 05.12.08 3 pilot episode was directed by Jason Bateman from “Arrested Develop- ment” fame ... And while this isn’t exactly the “Arrested Development” reunion movie we were all waiting for, it might just have to do for now: The second officially picked up series from FOX is an animated com- JENNIFER CADDICK edy from “Development” creator the buzz editor Mitchell Hurwitz and will feature by richard tinoco the voices of alums like Bateman, Will Arnett and Henry Winkler. The cartoon is currently titled, “Sit Down, Shut Up” ... RICHARD TINOCO arrested development Segueing away from FOX to The the buzz assistant editor Despite its downward spiral in the FOX Network where his re- CW, home of the fabulous “Gossip the ratings, “Lost” still plans to end cently produced $10 million 2-hour Girl,” the network’s “Beverly Hills, 90210” spin-off has recently tapped Josh Holloway on “Lost.” by its sixth season in 2010. After the pilot, “Fringe,” was picked up for a PHOTO COURTESY BY ABC writers’ strike, though, a cut down fall premiere ... Jennie Garth, better known by her in episodes means the next two sea- In other FOX news, the network alternative moniker as Kelly Taylor, sons will have an extra episode each, will also be rolling out two new se- to return in a recurring capacity ... IAN HAMILTON marking the count up from 16 to ries for the fall. “The Inn,” which A quick reminder that Garth executive editor 17. Finally, some good news post- will star Niecy Nash (“Reno 911!”) stayed with “Hills” for its 10 season strike .. -

Annual Newsletter 2019

Department of English ANNUAL NEWSLETTER 2019 Veronique Lee ’11 From Amherst to Uganda: a career in international development 1 WELCOME FROM THE CHAIR Acting Department Chair Donna LeCourt. Photo: D. Toomey Dear Friends and Alums, It’s an exciting and challenging time for by current faculty, alumni, and students efforts. Stay tuned for more and do be in the Department of English as we seek in April, offer opportunities for all of us touch if you would like to help us get the out new directions in English studies to reflect upon why the humanities and word out about how valuable an English (environmental humanities, gaming English in particular are so important major can be in the 21st century. Stay culture, Arab American literature) and in our times for not only careers but connected through our improved website, also understanding each other and our join us through LinkedIn, and keep abreast seek to help others understand what The Literary Arts Fair, one of many events featured positions globally. of our activities through Facebook and in the 2019 Juniper Festival. Photo: Noah Loving TABLE OF CONTENTS an English major can entail. Although nationally the number of English majors Instagram. Please use those venues to keep Department News ...........................................................................................4 continues to decline, and UMass is Department faculty continue to lead in us informed of your doings, as well. We want very much to know, and we may want The Troy Lectures on the Humanities and Public Life ........................5 not immune to such a trend, we are such endeavors, winning high prestige Thanks for editorial assistance are owed awards such as the MacArthur “genius” to tap your expertise! to Meg Caulmare and Jennifer Jacobson. -

Quince Trees- a Symbol of Fertility& the Quince Tree Is a Rare Asian Love

No.13 September 2010 Our little school magazine has become known worldwide! …thanks to our principal Mr.Jan Brna and our school counsellors who decided to reveal our two-year efforts In trying to write about our school,its students, projects, continual improvement strategy… Of course, this fact means even much greater responsibility to us and at the same time another burden for our school budget. We hope it will come a day when our magazine will be printed by using modern professional technology thus becoming a modern magazine like any other else…. … from now on you can find our new issue -just click on … „We are aware of the fact that the foundation and even more the persistence of our students´magazine in English means not only the great contribution to our school life ,our language & technology skills development,but also an additional burdeon to our school budget.Therefore,dear Mr. Principal ,we want to thank you for your understanding and allowing us to put our little magazine „SchoolDays― on our school´s official website. We will do our best to of through this little magazine of ours, to become in the .―were words of our grattitude.Our Principal, Mr.Jan Brna „Good Luck“- Warm words of our Principal, Jan Brna, at the welcoming program September 1st,the beginning of a “great adventure “for the first graders,setting out on a journey full of challenges,trials success and failures,learning how to overcome … Our Danka Nakicova,, Vlasta Lekarova Mariana Topolska and Vladislav Urbancek calling out the names of 77 first graders the youngest members of our students’community. -

Song Title Artist Genre

Song Title Artist Genre - General The A Team Ed Sheeran Pop A-Punk Vampire Weekend Rock A-Team TV Theme Songs Oldies A-YO Lady Gaga Pop A.D.I./Horror of it All Anthrax Hard Rock & Metal A** Back Home (feat. Neon Hitch) (Clean)Gym Class Heroes Rock Abba Megamix Abba Pop ABC Jackson 5 Oldies ABC (Extended Club Mix) Jackson 5 Pop Abigail King Diamond Hard Rock & Metal Abilene Bobby Bare Slow Country Abilene George Hamilton Iv Oldies About A Girl The Academy Is... Punk Rock About A Girl Nirvana Classic Rock About the Romance Inner Circle Reggae About Us Brooke Hogan & Paul Wall Hip Hop/Rap About You Zoe Girl Christian Above All Michael W. Smith Christian Above the Clouds Amber Techno Above the Clouds Lifescapes Classical Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Classic Rock Abracadabra Sugar Ray Rock Abraham, Martin, And John Dion Oldies Abrazame Luis Miguel Latin Abriendo Puertas Gloria Estefan Latin Absolutely ( Story Of A Girl ) Nine Days Rock AC-DC Hokey Pokey Jim Bruer Clip Academy Flight Song The Transplants Rock Acapulco Nights G.B. Leighton Rock Accident's Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Rock Accidents Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accordian Man Waltz Frankie Yankovic Polka Accordian Polka Lawrence Welk Polka According To You Orianthi Rock Ace of spades Motorhead Classic Rock Aces High Iron Maiden Classic Rock Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Country Acid Bill Hicks Clip Acid trip Rob Zombie Hard Rock & Metal Across The Nation Union Underground Hard Rock & Metal Across The Universe Beatles -

Title Author Call Number/Location Library 1964 973.923 US "I Will Never Forget" : Interviews with 39 Former Negro League Players / Kelley, Brent P

Title Author Call Number/Location Library 1964 973.923 US "I will never forget" : interviews with 39 former Negro League players / Kelley, Brent P. 920 K US "Master Harold"-- and the boys / Fugard, Athol, 822 FUG US "They made us many promises" the American Indian experience, 1524 to the present 973.049 THE US "We'll stand by the Union" Robert Gould Shaw and the Black 54th Massachusetts Regiment Burchard, Peter US "When I can read my title clear" : literacy, slavery, and religion in the antebellum South / Cornelius, Janet Duitsman. 305.5 US "Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria?" and other conversations about race / Tatum, Beverly Daniel. 305.8 US #NotYourPrincess : voices of Native American women / 971.004 #NO US 100 amazing facts about the Negro / Gates, Henry Louis, 973 GAT US 100 greatest African Americans : a biographical encyclopedia / Asante, Molefi K., 920 A US 100 Hispanic-Americans who changed American history Laezman, Rick j920 LAE MS 1001 things everyone should know about women's history Jones, Constance 305.409 JON US 1607 : a new look at Jamestown / Lange, Karen E. j973 .21 LAN MS 18th century turning points in U.S. history [videorecording] 1736-1750 and 1750-1766 DVD 973.3 EIG 2 US 1919, the year of racial violence : how African Americans fought back / Krugler, David F., 305.800973 KRU US 1920 : the year that made the decade roar / Burns, Eric, 973.91 BUR US 1954 : the year Willie Mays and the first generation of black superstars changed major league baseball forever / Madden, Bill.