Being Better Better – Living with Systems Intelligence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Five Accessories That Will Help Your Street Style Look Stand Out

(https://www.fashionforte.co.uk) Five Accessories that Will Help your Street Style Look Stand Out Posted on February 16, 2017 (https://www.fashionforte.co.uk/five- accessories-that-will-help-your-street-style-look-stand-out/) by Codelia Mantsebo (https://www.fashionforte.co.uk/author/codelia/) Facebook Twitter Google+ A great outt is all about nishing touches and as every street style maven knows, a well-chosen accessory is what pulls it all together. Make sure your fashion week outt (https://www.fashionforte.co.uk/london-fashion-week-streetstyle/) is a masterpiece with some nal details. Here are our top ve add-ons guaranteed to make your street style look stand out With every great street style look, there’s at least one accessory that helps make the look whole. So when it comes to creating a stand out outt, attention to detail is all important. We’re listing the most swoon-worthy accessories that will help you join the Instagram A list. Clutching it A post shared by The Styleograph (@thestyleograph) (https://www.instagram.com/p/BO-xzR_jLtn/) on… Ditch the oversized handbag in favour of a, chic clutch bag. They add detail to any outt and are a perfect nishing touch. To make your outt stand out, opt for medium sized clutch bags with attention- grabbing details. We’re talking bold colours, fringing, studs or fur. Fur clutches are particularly popular among Fashion Week goers. Play around with dierent shapes and maybe try a fold-over clutch bag. The lack of handle makes for a perfect street style shot as you clutch on to it. -

Newsclowntext.Pdf

THE NEWS CLOWN A NOVEL BY THOR GARCIA n EQUUS © Thor Garcia, 2012 ISBN 978-0-9571213-2-4 Equus Press Birkbeck College (William Rowe), 43 Gordon Square, London, WC1 H0PD, United Kingdom Typeset by lazarus Cover design by Ned Kash Printed in the Czech Republic by PB Tisk All rights reserved . Composed in Aldus, designed by Hermann Zapf (1954), named for the fifteenth- century Venetian printer Aldus Manutius. AUTHOR’S NOTE: The characters and situations in this work are wholly fictional and imaginary and do not portray, and are not intended to portray, any actual persons or parties. Any similarity to actual persons or events is coincidental, and no reference to the present day is intended or should be inferred. In Memory Elizabeth Bennett (1968 - 1993) Michael J. Gallant (1955 - 2005) THE NEWS CLOWN 1. Page 11 SHOCK CLAIM: Clown Says ‘I’m The Greatest!’ THOR declares his intention to explode “journalism” at its core, bringing the city to its knees in a rain of shame & indictments. He explains his work at CITIES NEWS SERVICES, covering BAY CITY’S crime & mayhem, his duty to bear witness. Introduction to the NEWS EDITOR KATE UHLI & the founding editor, DICK (10 news articles) TRIMBLES. 2. Page 24 LOADED: Clown Boards Midnight Train to Oblivion! THOR & JERRY visit CANDACE & HEATHER’S apartment. JERRY tells a story about an affair involving CANDACE & HEATHER’S mother & their family being threatened by the Russian mafia. HUGH arrives, everyone gets loaded & goes to play pool. Back at the apartment, THOR shares an intimacy with HEATHER, after which (1 news article) she tells him to leave. -

Arts Council of Northern Ireland National Lottery Fund Annual Report 2006-07

ARTS COUNCIL OF NORTHERN IRELAND NATIONAL LOTTERY FUND ANNUAL REPORT 2006-07 Presented to Parliament Pursuant to Section 34(3) of the National Lottery etc. Act 1993 (Incorporating HC414: Accounts for 2006-07 of the Arts Council of Northern Ireland Lottery Distribution, with the report of the Comptroller and Auditor General thereon, as ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 10 March 2008) London: The Stationery Office £18.55 3 © Crown Copyright 2008 The text in this document (excluding the Royal Arms and other departmental or agency logos) may be reproduced free of charge in any format or medium providing it is reproduced accurately and not used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as Crown copyright and the title of the document specified. Where we have identified any third party copyright material you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. For any other use of this material please write to Office of Public Sector Information, Information Policy Team, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 4DU or e-mail: [email protected] 4 CONTENTS Chairman’s Foreword 6 Chief Executive’s Introduction 7 Lottery Grants & Capital Committee Activity Report 8 Grants Awarded 1 April 2006 – 31 March 2007 10 Breakdown of Awards 2006/07 45 Policy and Financial Directions 48 National Lottery Distribution Account 61 Notes to the Accounts 84 Appendix 96 5 CHAIRMAN’S FOREWORD The Arts Council is the statutory body which, since the inception of the National Lottery in 1994, has been responsible for the administration and distribution of Lottery funds to the arts in Northern Ireland. -

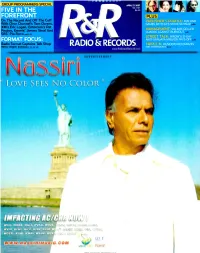

Radio & Records

R MEL .! GROUP PROGRAMMERS SPECIAL APRIL 27, 2007 NO. 1707 $6.50 O _ Off The Cuff PUBLISHER'S PROFILE: FUN AND With Clear Channel's Tom Owens, GAMES WITH EA'S STEVE SCHNUR XM's Eric Logan, Entercom's Pat MANAGEMENT: VALERIE GELLER Paxton, Emmis' Jimmy Steal An GUARDS AGAINST BURNOUT. SBS' Pio Ferro PP.12-21 STREET TALK: WRDW'S 21 -DAY ANTI -SANJAYA MISSION PAYS OFF Radio FIPMAt Captaillinnik Shop RADIO & RECORDS TRIPLE A: MUSEXPO RECOGNIZES With R &R Editors pp.22 -58 NIC HARCOURT www.RadioandRecords.com ADVERTISEMEÑT WCIL, WXXX, WGLI, WVAQ, WRZE, t> LU16c, l l .u" 1.0_1:.124, WVIQ, KFMI, WIFC, KISR, KQID, L4.21.4+. L'tA -(ú.6ti. WGER, KVKI, KWAV, WAHR, WJX = 1_titiLL, L't!R (_.L ' LEp:E WORLD Namiri www.americanradiohistory.com Leading Off Today's Program: The Incentives. PRESENTING LOUISIANA'S SOUND RECORDING INVESTOR TAX CREDIT. If you're looking to make some noise in the entertainment industry, Louisiana Economic Development invites you to experience the Sound Recording Investor Tzx Credit. It reimburses 10 -20 percent of your investment in scud recording, production, recording studios and infrastru:ture projects. Much like our film program. the Sound Recording Tax Credit is designed to boost record production by ncucing your costs. To learn more about this program and othe- incentives. call Sherri McConnell at 225.342.5832. LOUISOMIA ECONOMIC / DEVELOPMENT LouisianaForward.com/Entertainment www.americanradiohistory.com &R CONVENTION 2007 TAKES PLACE SEPTEMBER 26 -28 IN CHARLOTTE, N.C. REGISTER AT WWW.RADIOANDRECORDS.COM NewsroCu MOVER ON THE WEB Reich Place, Reich Time WLTW/New York Tops 2006 Imus Fallout Continues RCA Music Group regional promotion rep Revenue Earners The fallout from the firing of talk host Don Josh Reich is upped to director of top 40 field Clear Channel AC WLTW /NewYork was the nation's highest revcuue- generating radio Imus by CBS Radio continues. -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

Bulletin Spring 2014 Corrected 0.Pdf

THE EMILY DICKINSON INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY Volume 26, Number 1 May/June 2014 “The Only News I know / Is Bulletins all Day / From Immortality.” EMILY DICKINSON INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY Officers President: Martha Nell Smith Vice-President: Barbara Mossberg Secretary: Nancy Pridgen Treasurer: James C. Fraser Board Members Antoine Cazé Jonnie Guerra Nancy Pridgen Paul Crumbley Eleanor Heginbotham Eliza Richards Cindy Dickinson (Honorary Board Member) Suzanne Juhasz Martha Nell Smith Páraic Finnerty Barbara Mossberg Alexandra Socarides James C. Fraser Elizabeth Petrino Hiroko Uno Vivian Pollak Jane Wald (Honorary Board Member) Legal Advisor: [Position Open] Chapter Development Chair: Nancy Pridgen Nominations Chair: Alexandra Socarides Book Review Editor: [Position Open] Membership Chair: Elizabeth Petrino Bulletin Editor: Daniel Manheim Dickinson and the Arts Chair: Barbara Dana Journal Editor: Cristanne Miller Sustaining Members Mary Elizabeth K. Bernhard Robert Eberwein Barbara Mossberg Richard Brantley James C. Fraser Martha Nell Smith Jane D. Eberwein Jonnie G. Guerra Contributing Members Antoine Cazé Linda Healy Daniel Manheim Carolyn L. Cooley Eleanor Heginbotham Ethan Tarasov LeeAnn Gorthey Suzanne Juhasz Robin Tarasov Niels Kjaer EDIS gratefully acknowledges the generous financial contributions of these members. EDIS Bulletin (ISSN 1055-3932) is published twice yearly, May/June and November/December, by The Emily Dickinson International Society, Inc. Standard Mail non- profit postage is paid at Lexington, KY 40511. Membership in the Society -

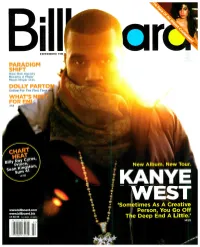

`Sometimes As a Creative

EXPERIENCE THE PARADIGM SHIFT How One Agency Became A Major Music Player >P.25 DOLLY PARTO Online For The First Tim WHAT'S FOR >P.8 New Album. New Tour. KANYE WEST `Sometimes As A Creative www.billboard.com Person, You Go Off www.billboard.biz US $6.99 CAN $8.99 UK E5.50 The Deep End A Little.' >P.22 THE YEAR MARK ROHBON VERSION THE CRITICS AIE IAVIN! "HAVING PRODUCED AMY WINEHOUSE AND LILY ALLEN, MARK RONSON IS ON A REAL ROLL IN 2007. FEATURING GUEST VOCALISTS LIKE ALLEN, IN NOUS AND ROBBIE WILLIAMS, THE WHOLE THING PLAYS LIKE THE ULTIMATE HIPSTER PARTY MIXTAPE. BEST OF ALL? `STOP ME,' THE MOST SOULFUL RAVE SINCE GNARLS BARKLEY'S `CRAZY." PEOPLE MAGAZINE "RONSON JOYOUSLY TWISTS POPULAR TUNES BY EVERYONE FROM RA TO COLDPLAY TO BRITNEY SPEARS, AND - WHAT DO YOU KNOW! - IT TURNS OUT TO BE THE MONSTER JAM OF THE SEASON! REGARDLESS OF WHO'S OH THE MIC, VERSION SUCCEEDS. GRADE A" ENT 431,11:1;14I WEEKLY "THE EMERGING RONSON SOUND IS MOTOWN MEETS HIP -HOP MEETS RETRO BRIT -POP. IN BRITAIN, `STOP ME,' THE COVER OF THE SMITHS' `STOP ME IF YOU THINK YOU'VE HEARD THIS ONE BEFORE,' IS # 1 AND THE ALBUM SOARED TO #2! COULD THIS ROCK STAR DJ ACTUALLY BECOME A ROCK STAR ?" NEW YORK TIMES "RONSON UNITES TWO ANTITHETICAL WORLDS - RECENT AND CLASSIC BRITPOP WITH VINTAGE AMERICAN R &B. LILY ALLEN, AMY WINEHOUSE, ROBBIE WILLIAMS COVER KAISER CHIEFS, COLDPLAY, AND THE SMITHS OVER BLARING HORNS, AND ORGANIC BEATS. SHARP ARRANGING SKILLS AND SUITABLY ANGULAR PERFORMANCES! * * * *" SPIN THE SOUNDTRACK TO YOUR SUMMER! THE . -

2008-05-12.Pdf

1 2 2 BUZZ 05.12.08 daily.titan daily.titan BUZZ 05.12.08 3 pilot episode was directed by Jason Bateman from “Arrested Develop- ment” fame ... And while this isn’t exactly the “Arrested Development” reunion movie we were all waiting for, it might just have to do for now: The second officially picked up series from FOX is an animated com- JENNIFER CADDICK edy from “Development” creator the buzz editor Mitchell Hurwitz and will feature by richard tinoco the voices of alums like Bateman, Will Arnett and Henry Winkler. The cartoon is currently titled, “Sit Down, Shut Up” ... RICHARD TINOCO arrested development Segueing away from FOX to The the buzz assistant editor Despite its downward spiral in the FOX Network where his re- CW, home of the fabulous “Gossip the ratings, “Lost” still plans to end cently produced $10 million 2-hour Girl,” the network’s “Beverly Hills, 90210” spin-off has recently tapped Josh Holloway on “Lost.” by its sixth season in 2010. After the pilot, “Fringe,” was picked up for a PHOTO COURTESY BY ABC writers’ strike, though, a cut down fall premiere ... Jennie Garth, better known by her in episodes means the next two sea- In other FOX news, the network alternative moniker as Kelly Taylor, sons will have an extra episode each, will also be rolling out two new se- to return in a recurring capacity ... IAN HAMILTON marking the count up from 16 to ries for the fall. “The Inn,” which A quick reminder that Garth executive editor 17. Finally, some good news post- will star Niecy Nash (“Reno 911!”) stayed with “Hills” for its 10 season strike .. -

Quince Trees- a Symbol of Fertility& the Quince Tree Is a Rare Asian Love

No.13 September 2010 Our little school magazine has become known worldwide! …thanks to our principal Mr.Jan Brna and our school counsellors who decided to reveal our two-year efforts In trying to write about our school,its students, projects, continual improvement strategy… Of course, this fact means even much greater responsibility to us and at the same time another burden for our school budget. We hope it will come a day when our magazine will be printed by using modern professional technology thus becoming a modern magazine like any other else…. … from now on you can find our new issue -just click on … „We are aware of the fact that the foundation and even more the persistence of our students´magazine in English means not only the great contribution to our school life ,our language & technology skills development,but also an additional burdeon to our school budget.Therefore,dear Mr. Principal ,we want to thank you for your understanding and allowing us to put our little magazine „SchoolDays― on our school´s official website. We will do our best to of through this little magazine of ours, to become in the .―were words of our grattitude.Our Principal, Mr.Jan Brna „Good Luck“- Warm words of our Principal, Jan Brna, at the welcoming program September 1st,the beginning of a “great adventure “for the first graders,setting out on a journey full of challenges,trials success and failures,learning how to overcome … Our Danka Nakicova,, Vlasta Lekarova Mariana Topolska and Vladislav Urbancek calling out the names of 77 first graders the youngest members of our students’community. -

Yakov Freidman Felt the Skids to the Bell Helicopter Touch

22800 1 Summer Olympic Games, Munich, Germany September 5, 1972 akov Freidman felt the skids to the Bell helicopter touch down, Yand knew they had reached the first leg of their destination. Next stop: Cairo. Seeing only darkness behind the blindfold cinched to his head, he rubbed the leg of the Israeli athlete next to him, using the rope around his wrists to make contact. A small effort at solidarity. A reassurance that everything was going to turn out okay. That they would all be released alive from the maniacal Palestinian terrorists that had captured them. He didn’t believe it. And neither did the man he rubbed. The Pales- tinians had already killed enough people to prove that wouldn’t happen. The engine whine began to decrease, the shuddering of the frame growing still. He heard the terrorist in the hold with them shout at the German pilots, screaming in English to keep their hands in sight. He only assumed the pilots had, because the shouting stopped. He sat in silence for an eternity, waiting, straining his ears to hear something. Anything to indicate what was transpiring. He hunched his shoulders and rubbed the knot of the blindfold on his back, causing it to shift a millimeter. Enough to let in a sliver of light and a small piece of vision. 9780525953982_DaysOfRage_TX.indd 1 3/7/14 10:58 AM 22800 2 ⁄ BRAD TAYLOR He saw two of the terrorists walking to an unlit Boeing 727, parked off to the edge of whatever airfield they had landed within. They went up the stairs, took one look inside, then began running back down. -

Modern Optical Retailing Strategies: Anti-Reflective and Mirror Lenses

Modern Optical Retailing Strategies: Anti-Reflective and Mirror Lenses INTRODUCTION Success in today’s highly competitive eyewear retailing market requires new tools and strategies. This paper presents one such opportunity that up until recently has been unavailable to in-store retail labs and small-to-midsize optical labs — the ability to produce quality anti-reflective (AR) lenses and mirrored sun lenses in-house.And by doing so, significantly increase profitability and customer satisfaction. This ability has been made possible by the introduction of smaller, in-house AR Coating Systems geared to the throughput, space and budget requirements of the in-office lab. These new compact systems are designed to deliver big performance in a small footprint and offer a simplified approach to providing anti-reflective and mirror coatings. The right coating system enables eyewear retailers and small optical labs to offer anti-reflective and mirror coatings like those produced by “big box” coating companies, at a fraction of the cost and time required for traditional coatings. OPPORTUNITY #1 - ANTI-REFLECTIVE LENSES It’s well known that the U.S. eyewear market lags far behind those of other developed countries in the percentage of eyeglasses sold with anti-reflective lenses. Finding out how selling more anti-reflective lenses improves the profitability of your How far? According to a report published by The Vision Council in March business is a pretty simple (and eye-opening) 2016, only 30.1% of eyeglass lenses sold in the U.S. include anti-reflective exercise: coating, compared with 64.4% in Canada. In Europe, AR lenses account for more than 64% of eyeglass lenses sold in Germany, 61.2% sold in Italy, 59.6% 1. -

Song Title Artist Genre

Song Title Artist Genre - General The A Team Ed Sheeran Pop A-Punk Vampire Weekend Rock A-Team TV Theme Songs Oldies A-YO Lady Gaga Pop A.D.I./Horror of it All Anthrax Hard Rock & Metal A** Back Home (feat. Neon Hitch) (Clean)Gym Class Heroes Rock Abba Megamix Abba Pop ABC Jackson 5 Oldies ABC (Extended Club Mix) Jackson 5 Pop Abigail King Diamond Hard Rock & Metal Abilene Bobby Bare Slow Country Abilene George Hamilton Iv Oldies About A Girl The Academy Is... Punk Rock About A Girl Nirvana Classic Rock About the Romance Inner Circle Reggae About Us Brooke Hogan & Paul Wall Hip Hop/Rap About You Zoe Girl Christian Above All Michael W. Smith Christian Above the Clouds Amber Techno Above the Clouds Lifescapes Classical Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Classic Rock Abracadabra Sugar Ray Rock Abraham, Martin, And John Dion Oldies Abrazame Luis Miguel Latin Abriendo Puertas Gloria Estefan Latin Absolutely ( Story Of A Girl ) Nine Days Rock AC-DC Hokey Pokey Jim Bruer Clip Academy Flight Song The Transplants Rock Acapulco Nights G.B. Leighton Rock Accident's Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Rock Accidents Will Happen Elvis Costello Classic Rock Accordian Man Waltz Frankie Yankovic Polka Accordian Polka Lawrence Welk Polka According To You Orianthi Rock Ace of spades Motorhead Classic Rock Aces High Iron Maiden Classic Rock Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Country Acid Bill Hicks Clip Acid trip Rob Zombie Hard Rock & Metal Across The Nation Union Underground Hard Rock & Metal Across The Universe Beatles