Intent of the Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Verbs Show an Action (Eg to Run)

VERBS Verbs show an action (e.g. to run). The tricky part is that sometimes the action can't be seen on the outside (like run) – it is done on the inside (e.g. to decide). Sometimes the action even has to do with just existing, in other words to be (e.g. is, was, are, were, am). Tenses The three basic tenses are past, present and future. Past – has already happened Present – is happening Future – will happen To change a word to the past tense, add "-ed" (e.g. walk → walked). ***Watch out for the words that don't follow this (or any) rule (e.g. swim → swam) *** To change a word to the future tense, add "will" before the word (e.g. walk → will walk BUT not will walks) Exercise 1 For each word, write down the correct tense in the appropriate space in the table below. Past Present Future dance will plant looked runs shone will lose put dig Spelling note: when "-ed" is added to a word ending in "y", the "y" becomes an "i" e.g. try → tried These are the basic tenses. You can break present tense up into simple present (e.g. walk), present perfect (e.g. has walked) and present continuous (e.g. is walking). Both past and future tenses can also be broken up into simple, perfect and continuous. You do not need to know these categories, but be aware that each tense can be found in different forms. Is it a verb? Can it be acted out? no yes Can it change It's a verb! tense? no yes It's NOT a It's a verb! verb! Exercise 2 In groups, decide which of the words your teacher gives you are verbs using the above diagram. -

Modals and Auxiliaries 12

Verbs: Modals and Auxiliaries 12 An auxiliary is a helping verb. It is used with a main verb to form a verb phrase. For example, • She was calling her friend. Here the word calling is the main verb and the word was is an auxiliary verb. The words be , have , do , can , could , may , might , shall , should , must , will , would , used , need , dare , ought are called auxiliaries . The verbs be, have and do are often referred to as primary auxiliaries. They have a grammatical function in a sentence. The rest in the above list are called modal auxiliaries, which are also known as modals. They express attitude like permission, possibility, etc. Note the forms of the primary auxiliaries. Auxiliary verbs Present tense Past tense be am, is, are was, were do do, does did have has, have had The table below illustrates the application of these primary verbs. Primary auxiliary Function Example used in the formation of She is sewing a dress. continuous tenses I am leaving tomorrow. be in sentences where the The missing child was action is more important found. than the subject 67 EBC-6_Ch19.indd 67 8/12/10 11:47:38 PM when followed by an We are to leave next infinitive, it is used to week. indicate a plan or an arrangement denotes command You are to see the Principal right now. used to form the perfect The carpenter has tenses worked well. have used with the infinitive I had to work that day. to indicate some kind of obligation used to form the He doesn’t work at all. -

Verbnet Guidelines

VerbNet Annotation Guidelines 1. Why Verbs? 2. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource 3. VerbNet Contents a. The Hierarchy b. Semantic Role Labels and Selectional Restrictions c. Syntactic Frames d. Semantic Predicates 4. Annotation Guidelines a. Does the Instance Fit the Class? b. Annotating Verbs Represented in Multiple Classes c. Things that look like verbs but aren’t i. Nouns ii. Adjectives d. Auxiliaries e. Light Verbs f. Figurative Uses of Verbs 1 Why Verbs? Computational verb lexicons are key to supporting NLP systems aimed at semantic interpretation. Verbs express the semantics of an event being described as well as the relational information among participants in that event, and project the syntactic structures that encode that information. Verbs are also highly variable, displaying a rich range of semantic and syntactic behavior. Verb classifications help NLP systems to deal with this complexity by organizing verbs into groups that share core semantic and syntactic properties. VerbNet (Kipper et al., 2008) is one such lexicon, which identifies semantic roles and syntactic patterns characteristic of the verbs in each class and makes explicit the connections between the syntactic patterns and the underlying semantic relations that can be inferred for all members of the class. Each syntactic frame in a class has a corresponding semantic representation that details the semantic relations between event participants across the course of the event. In the following sections, each component of VerbNet is identified and explained. VerbNet: A Verb Class Lexical Resource VerbNet is a lexicon of approximately 5800 English verbs, and groups verbs according to shared syntactic behaviors, thereby revealing generalizations of verb behavior. -

Adverbs in Kenyang

International Journal of Linguistics and Communication June 2015, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 112-133 ISSN: 2372-479X (Print) 2372-4803 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijlc.v3n1a13 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijlc.v3n1a13 Adverbs in Kenyang Tabe Florence A. E1 Abstract Kenyang (a Niger-Congo language spoken in Cameroon) has both pure and derived adverbs. Characteristic features of Kenyang adverbs can be captured from event structure constituting different functional projections in the syntax. Thus the behaviour of adverbs in this language is inextricably bound to both syntactic and semantic phenomena. The nature of the interface between them is explained based on their distribution and properties in the language. The adverbs can appear left-adjoined or right-adjoined to the verb. From a cartographic perspective, Kenyang adverbs can occupy different functional heads comprising the CP, IP and VP respectively. Each syntactic position affects the semantics of the proposition. The possibility of adverb stacking is constrained by the pragmatics of the semantic zones and the co-occurrence and ordering restrictions in the syntax. The ordering is a relative linear proximity rather than a fixed order. The theoretical relevance of the analysis is obtained from the assumption that there is a feasible correlation between the classes of adverbs and independently motivated functional projections, on the one hand, and on the existence of a one-to-one correlation between syntactic positions and semantic structures, on the other hand. Keywords: event structure, adverb taxonomy, interface, adverb focus, adverb ordering 1.0 Introduction Adverbs have been treated as the least homogenous category to define in language because their analysis as a grammatical category remains peripheral to the basic argument structure of the sentence. -

Defective Causative and Perception Verb Constructions in Romance. a Minimalist Approach to Infinitival and Subjunctive Clauses

Defective causative and perception verb constructions in Romance. A minimalist approach to infinitival and subjunctive clauses Elena Ciutescu Doctoral Dissertation Supervised by Dr. Jaume Mateu Fontanals Programa de Doctorat Ciència Cognitiva i Llenguatge Centre de Lingüística Teòrica Departament de Filologia Catalana Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2018 Eu nu strivesc corola de minuni a lumii şi nu ucid cu mintea tainele, ce le-ntâlnesc în calea mea în flori, în ochi, pe buze ori morminte. Lumina altora sugrumă vraja nepătrunsului ascuns în adâncimi de întuneric, dar eu, eu cu lumina mea sporesc a lumii taină- şi-ntocmai cum cu razele ei albe luna nu micşorează, ci tremurătoare măreşte şi mai tare taina nopţii, aşa îmbogăţesc şi eu întunecata zare cu largi fiori de sfânt mister şi tot ce-i nenţeles se schimbă-n nenţelesuri şi mai mari sub ochii mei- căci eu iubesc şi flori şi ochi şi buze şi morminte. Lucian Blaga – ‘Eu nu strivesc corola de minuni a lumii’ (Poemele luminii, 1919) Abstract The present dissertation explores aspects of the micro-parametric variation found in defective complements of causative and perception verbs in Romance. The study deals with infinitival and subjunctive clauses with overt lexical subjects in three Romance languages: Spanish, Catalan and Romanian. I focus on various syntactic phenomena of the Case-agreement system in environments that exhibit defective C-T dependencies (in the spirit of Chomsky 2000; 2001, Gallego 2009; 2010; 2014). I argue in favour of a unifying account of the non- finite complementation of causative and perception verbs, investigating at the same time the mechanisms responsible for the micro-parametric variation exhibited by the three languages. -

2008Impersonalization.Pdf

TRPS 211 Dispatch: 24.6.08 Journal: TRPS CE: Blackwell Journal Name Manuscript No. -B Author Received: No. of pages: 23 PE: Mahendrakumar Transactions of the Philological Society Volume 106:2 (2008) 1–23 1 2 INTRODUCTION: IMPERSONALIZATION FROM A 3 SUBJECT-CENTRED VS. AGENT-CENTRED 4 PERSPECTIVE 5 6 By ANNA SIEWIERSKA 7 Lancaster University 8 9 10 1. PRELIMINARIES 11 The notion of impersonality is a broad and disparate one. In the 12 main, impersonality has been studied in the context of Indo- 13 European languages and especially Indo-European diachronic 14 linguistics (see e.g. Seefranz-Montag 1984; Lambert 1998; Bauer 15 2000). It is only very recently that discussions of impersonal 16 constructions have been extended to languages outside Europe (see 17 e.g. Aikhenvald et al. 2001; Creissels 2007; Malchukov 2008 and the 18 papers in Malchukov & Siewierska forthcoming). The currently 19 available analyses of impersonal constructions within theoretical 20 models of grammar are thus all based on European languages. The 21 richness of impersonal constructions in European languages, has, 22 however, ensured that they be given due attention within any model 23 of grammar with serious aspirations. Consequently, the linguistic 24 literature boasts of many theory-specific analyses of various 25 impersonal constructions. The last years have seen a heightening 26 of interest in impersonality and a series of new analyses of 27 impersonal constructions. The present special issue brings together 28 five of these analyses spanning the formal ⁄ functional-cognitive 29 divide. Three of the papers in this volume, by Divjak and Janda, by 30 Afonso and by Helasvuo and Vilkuna, offer analyses couched 31 within or inspired by different versions of the marriage of 32 Construction Grammar and Cognitive Grammar as developed by 33 Langacker (1991), Goldberg (1995, 2006) and Croft (2001). -

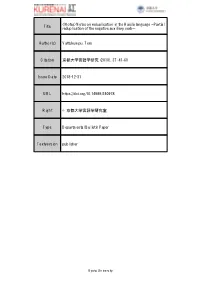

Title <Notes>Notes on Reduplication in the Haisla Language --Partial

<Notes>Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language --Partial Title reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb-- Author(s) Vattukumpu, Tero Citation 京都大学言語学研究 (2018), 37: 41-60 Issue Date 2018-12-31 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/240978 Right © 京都大学言語学研究室 Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University 京都大学言語学研究 (Kyoto University Linguistic Research) 37 (2018), 41 –60 Notes on reduplication in the Haisla language Ü Partial reduplication of the negative auxiliary verb Ü Tero Vattukumpu Abstract: In this paper I will point out that, according to my data, a plural form of the negative auxiliary verb formed by means of partial reduplication exists in the Haisla language in contrary to a description on the topic in a previous study. The plural number of the subject can, and in many cases must, be indicated by using a plural form of at least one of the components of the predicate, i.e. either an auxiliary verb (if there is one), the semantic head of the predicate or both. Therefore, I have examined which combinations of the singular and plural forms of the negative auxiliary verb and different semantic heads of the predicate are judged to be acceptable by native speakers of Haisla. My data suggests that – at least at this point – it seems to be impossible to make convincing generalizations about any patterns according to which the acceptability of different combinations could be determined *. Keywords: Haisla, partial reduplication, negative auxiliary verb, plural, root extension 1 Introduction The purpose of this paper is to introduce some preliminary notes about reduplication in the Haisla language from a morphosyntactic point of view as a first step towards a better understanding and a more comprehensive analysis of all the possible patterns of reduplication in the language. -

4 the Sentence, Auxiliary Verbs, and Recursion

Introduction to Configurational Syntax Chapter 4 : Chapter 4. 4 The Sentence, Auxiliary Verbs, and Recursion 4.1 Introduction In this chapter the sentence and the verb (predicate) phrase whose head is an auxiliary verb are formally introduced. These two categories do not appear to follow the universal expansion of XP proposed in Chapter 2. In the Principles and Parameters framework of syntax the structure of the sentence can be shown to fol- low the universal expansion of XP. However, the analysis of the sentence given the category CP1 is considered too complex to be covered here. The analyses given here follow the earlier standard views on the structure of the sentence. 4.2 The Sentence At first glance, note that the sentence contains a NP and a VP: (297)a. The moon orbits around the earth. b. [NP the moon ] [VP orbits around the earth ]. We can state the expansion of S (sentence) as: (298) The Expansion of S [1] S ˘ NP VP. The structure for (297 is: (299) [S [NP The moon ] [VP orbits around the earth]] Up to this point we have claimed that all constituents contain a head and a complement. If this is the case then what is the head of S? In advanced work it can be shown to be either tense in some points of view, or the verb in other points of view. In some sense both points of view or correct; however, it is too complex a matter to attempt to explain this here. We will adopt the above expansion, which is traditional and found in most texts, and note that the verb is the unexplained head of the sentence. -

Verb Phrase, Or VP

VP Study Guide In the Logic Study Guide, we ended with a logical tree diagram for WANT (BILL, LEAVE (MARY)), in both unlabelled: WANT BILL LEAVE MARY and labelled versions: P WANT BILL P LEAVE MARY We remarked that one could label the Predicate and Argument nodes as well, and that it was common to use S instead of P to label propositions in such logical tree structures in linguistics. It is also com- mon, in practice, to use V to label Predicates, and N (or NP, standing for Noun Phrase) to label Ar- guments. This would produce the following diagram: S V NP NP Subject Formation WANT BILL S V NP LEAVE MARY Note that, while these two predicates are in fact verbs, and the arguments are nouns, that’s not always the case, and one may use V loosely to label any Predicate node, whatever its syntactic class might be. This kind of structural description, intermediate between logic and surface syntax, is called a deep structure; we say this diagram represents the deep structure of Bill wants Mary to leave. Roughly speaking, deep structures are intended to represent the meaning of the sentence, stripped to its essentials. The deep structures are then related to the actual sentence by a series of relational rules. For instance, one such rule is that in English, there must be a subject NP, and it precedes the verb, instead of coming after it, as here. So we relate this structure with the following one by a rule of Subject Formation, which applies to every deep structure towards the end of the derivation (the series of rule applications; a number of other rules would have already applied earlier, producing the other differences). -

Animacy in Sentence Processing Across Languages: an Information-Theoretic Prospective

ANIMACY IN SENTENCE PROCESSING ACROSS LANGUAGES: AN INFORMATION-THEORETIC PROSPECTIVE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zhong Chen August 2014 c 2014 Zhong Chen ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ANIMACY IN SENTENCE PROCESSING ACROSS LANGUAGES: AN INFORMATION-THEORETIC PROSPECTIVE Zhong Chen, Ph.D. Cornell University August 2014 This dissertation is concerned with different sources of information that affect human sentence comprehension. It focuses on the way that syntactic rules in- teract with non-syntactic cues in real-time processing. It develops the idea first introduced in the Competition Model of MacWhinney in the late 1980s such that the weight of a linguistic cue varies among languages. The dissertation addresses this problem from an information-theoretic prospective. The proposed Entropy Reduction metric (Hale, 2003) combines corpus-retrieved attestation frequencies with linguistically-motivated gram- mars. It derives a processing asymmetry called the Subject Advantage that has been observed across languages (Keenan & Comrie, 1977). The modeling re- sults are consistent with the intuitive structural expectation idea, namely that subject relative clauses, as a frequent structure, are easier to comprehend. How- ever, the present research takes this proposal one step further by illustrating how the comprehension difficulty profile reflects uncertainty over different ini- tial substrings. It highlights particular disambiguation -

Berkeley Linguistics Society

PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-SECOND ANNUAL MEETING OF THE BERKELEY LINGUISTICS SOCIETY February 10-12, 2006 SPECIAL SESSION on THE LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS OF OCEANIA Edited by Zhenya Antić Charles B. Chang Clare S. Sandy Maziar Toosarvandani Berkeley Linguistics Society Berkeley, CA, USA Berkeley Linguistics Society University of California, Berkeley Department of Linguistics 1203 Dwinelle Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-2650 USA All papers copyright © 2012 by the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0363-2946 LCCN 76-640143 Printed by Sheridan Books 100 N. Staebler Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS A note regarding the contents of this volume ........................................................ iii Foreword ................................................................................................................ iv SPECIAL SESSION Oceania, the Pacific Rim, and the Theory of Linguistic Areas ...............................3 BALTHASAR BICKEL and JOHANNA NICHOLS Australian Complex Predicates ..............................................................................17 CLAIRE BOWERN Composite Tone in Mian Noun-Noun Compounds ...............................................35 SEBASTIAN FEDDEN Reconciling meng- and NP Movement in Indonesian ...........................................47 CATHERINE R. FORTIN The Role of Animacy in Teiwa and Abui (Papuan) ..............................................59 MARIAN KLAMER AND FRANTIŠEK KRATOCHVÍL A Feature Geometry of the Tongan Possessive Paradigm .....................................71 -

Simple And-Relative Clauses in Panare Spike Gildea A

ii SIMPLE AND-RELATIVE CLAUSES IN PANARE APPROVED: by SPIKE GILDEA A THESIS Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 1989 iii iv An Abstract of the Thesis of Spike Gildea for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Linguistics to be takaa 1989 Title: SIMPLE AND RELATIVE CLAUSES IN PANARE Approved: Copyright 1989 Spike Gildea This thesis is a description, based on original field work, of simple and relative clauses in Panare, a Cariban language spoken by 2000-2500 people in central Venezuela. The three types of simple clauses described are past tenses, predicate nominals, and an aspect- inflected verb with an auxiliary. The set of aspect inflections in Panare is historically derived from a set of nominalizing suffixes, and in related languages, cognates to the Panare aspect suffixes are still nominalizers. The evolution from nominalizer to aspect in Panare follows a previously described pattern language of change, one which appears in studies of both language acquisition and of historical change. The two types of relative clause strategy described are finite, based on the past tense verbs and on one the auxiliaries for the aspect- inflected verb, and the less finite, based on the aspect-inflected verb itself. VITA NAME OF AUTHOR: Spike Lawrence Owen Gildea PLACE OF BIRTH: Salem, Oregon DATE OF BIRTH: June 17, 1961 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SGHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon Washington University