Chapter One the Postman Knocks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Becoming a Translator Second Edition

Becoming a Translator Second Edition "Absolutely up-to-date and state of the art in the practical as well as theoretical aspect of translation, this new edition of Becoming a Translator retains the strength of the first edition while offering new sections on current issues. Bright, lively and witty, the book is filled with entertaining and thoughtful examples; I would recommend it to teachers offering courses to beginning and advanced students, and to any translator who wishes to know where the field is today." Malcolm Hayward, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA "A very useful book ... I would recommend it to students who aim at a career in translation as a valuable introduction to the profession and an initiation into the social and transactional skills which it requires." Mike Routledge, Royal Holloway, University of London, UK Fusing theory with advice and information about the practicalities of translating, Becoming a Translator is the essential resource for novice and practising translators. The book explains how the market works, helps translators learn how to translate faster and more accurately, as well as providing invaluable advice and tips about how to deal with potential problems such as stress. The second edition has been revised and updated throughout, offering: • a "useful contacts" section • new exercises and examples • new e-mail exchanges to show how translators have dealt with a range of real problems • updated further reading sections • extensive up-to-date information about new translation technologies. Offering suggestions for discussion, activities, and hints for the teaching of translation, the second edition of Becoming a Translator remains invaluable for students on and teachers of courses in translation, as well as for professional translators and scholars of translation and language. -

Parliamentary Debates House of Commons Official Report General Committees

PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT GENERAL COMMITTEES Public Bill Committee FINANCE BILL (Except clauses 1, 5 to 7, 11, 72 to 74 and 112, schedule 1, and certain new clauses and new schedules) Eleventh Sitting Tuesday 10 June 2014 (Afternoon) CONTENTS Programme order amended. CLAUSES 90 to 93 agreed to. SCHEDULE 16 agreed to. CLAUSES 94 and 95 agreed to. SCHEDULE 17 agreed to. CLAUSES 96 to 100 agreed to. SCHEDULE 18 agreed to. CLAUSES 101 to 106 agreed to. SCHEDULE 19 agreed to. CLAUSES 107 and 108 agreed to. SCHEDULE 20 agreed to. CLAUSES 109 and 110 agreed to. SCHEDULE 21 agreed to. CLAUSES 111 and 113 agreed to. SCHEDULE 22 agreed to. CLAUSES 114 to 117 agreed to. Adjourned till Thursday 12 June at Two o’clock. Written evidence reported to the House. PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS LONDON – THE STATIONERY OFFICE LIMITED £6·00 PBC (Bill 190) 2014 - 2015 Members who wish to have copies of the Official Report of Proceedings in General Committees sent to them are requested to give notice to that effect at the Vote Office. No proofs can be supplied. Corrigenda slips may be published with Bound Volume editions. Corrigenda that Members suggest should be clearly marked in a copy of the report—not telephoned—and must be received in the Editor’s Room, House of Commons, not later than Saturday 14 June 2014 STRICT ADHERENCE TO THIS ARRANGEMENT WILL GREATLY FACILITATE THE PROMPT PUBLICATION OF THE BOUND VOLUMES OF PROCEEDINGS IN GENERAL COMMITTEES © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2014 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. -

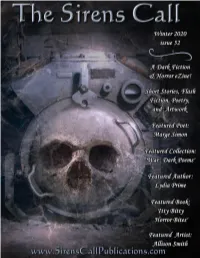

The Sirens Call Ezine Throughout the Years

1 Table of Contents pg. 04 - The Cave| H.B. Diaz pg. 110 - Mud Baby | Lori R. Lopez pg. 07 - Honeysuckle | T.S. Woolard pg. 112 - On Eternity’s Brink | Lori R. Lopez pg. 08 - Return to Chaos | B. T. Petro pg. 115 - Sins for the Father | Marcus Cook pg. 08 - Deathwatch | B. T. Petro pg. 118 - The Island | Brian Rosenberger pg. 09 - A Cup of Holiday Cheer | KC Grifant pg. 120 - Old John | Jeffrey Durkin pg. 12 - Getting Ahead | Kevin Gooden pg. 123 - Case File | Pete FourWinds pg. 14 - Soup for Mother | Sharon Hajj pg. 124 - Filling in a Hole | Radar DeBoard pg. 15 - A Dying Moment | Gavin Gardiner pg. 126 - Butterfly | Lee Greenaway pg. 17 - Snake | Natasha Sinclair pg. 130 - Death’s Gift | Naching T. Kassa pg. 19 - The Cold Death | Nicole Henning pg. 132 - Waste Not | Evan Baughfman pg. 21 - The Burning Bush | O. D. Hegre pg. 132 - Rainbows and Unicorns | Evan Baughfman pg. 24 - The Wishbone | Eileen Taylor pg. 133 - Salty Air | Sonora Taylor pg. 27 - Down by the River Walk | Matt Scott pg. 134 - Death is Interesting | Radar DeBoard pg. 30 - The Reverend I Milkana N. Mingels pg. 134 - It Wasn’t Time | Radar DeBoard pg. 31 - Until Death Do Us Part | Candace Meredith pg. 136 - Future Fuck | Matt Martinek pg. 33 - A Grand Estate | Zack Kullis pg. 139 - The Little Church | Eduard Schmidt-Zorner pg. 36 - The Chase | Siren Knight pg. 140 - Sweet Partings | O. D. Hegre pg. 38 - Darla | Miracle Austin pg. 142 - Christmas Eve on the Rudolph Express | Sheri White pg. 39 - I Remember You | Judson Michael Agla pg. -

Low Resolution Pictures

Low resolution pictures highfieldsoffice.wordpress.com BlogBook 2 ©2016 highfieldsoffice.wordpress.com Contents 1 2013 13 1.1 January .......................................... 14 1.1.1 It’s January 2013 & The ”Highfields Curfew” Is Still In Place! (2013-01-04 18:37) 15 1.1.2 New Updates On Mahdi Hashi (Daily Mail) & Leicester’s Thurnby Lodge Drama (Leicester Mercury) (2013-01-06 11:21) ..................... 18 1.1.3 Looking Into The Future of Voting Behaviour in UK: What Might Happen When The British-Minorities Voters Grow? (2013-01-07 16:29) . 25 1.1.4 The Independent: How The British MI5 Coerce British-Somalis to Spy On Their Own Communities (2013-01-07 18:47) ...................... 30 1.1.5 For Your Self-Enlightement: Articles From This Week Newspapers (2013-01-11 12:50) ................................ 35 1.1.6 Spinney Hills LPU: A Militarized Police Station Inside The ”Local Terrorists Hotbed”!!!!! (2013-01-12 16:17) ......................... 37 1.1.7 Glenn Greenwald (The Guardian): In 4-Years, The West Have Bombed & Invaded 8 Muslim Nations (Is This not a ’War on Islam’?, he asks) (2013-01-15 11:48) . 39 1.1.8 St.Phillips Centre: Your ”Friendly” Inter-Faith Society or A Church/Diocese With A Secret? (Doubling as a Counter-Terrorism & ”Re-Education” Centre) (2013-01-19 10:29) ................................ 46 1.1.9 The Daily Mail’s First Exclusive Interview With Mahdi Hashi in The New York Jail: The Torture in Djibouti Ordeal In the Hands of CIA (with British Government ”Acquiescence”) (2013-01-20 10:36) ....................... 49 1.1.10 Important Additional Information for Muslims & Counter-Terrorism (and those in Leicester on FMO) and A Great Reading Collection from Public Intelligence (2013-01-20 19:11) ............................... -

Newfolk Ndif: Making a Big Apple Crumble...Chapter 1

Newfolk NDiF: Making a Big Apple Crumble...Chapter 1 New Directions in Folklore 6 June 2002 Newfolk :: NDiF :: Issue 6 :: Chapter 1 :: Page 1:: Page 2 :: Chapter 2 :: References Making a Big Apple Crumble: The Role of Humor in Constructing a Global Response to Disaster1 Bill Ellis Chapter One: Introduction On the morning of September 11, 2001, terrorists associated with Osama bin Laden's al-Qaida, a fundamentalist Islamic political movement, hijacked four American jetliners. Two were crashed into the twin towers of New York's World Trade Center, causing them to collapse with catastrophic loss of life. A third was crashed into the Pentagon, costing an additional 189 lives, while passengers on a fourth evidently attacked the hijackers, causing the plane to crash in a rural area in western Pennsylvania with the loss of all 44 persons aboard. Much of the drama was played out live on national television, including the crash of the second plane into the South Tower at 9:03 AM and both towers' collapse, at 10:05 and 10:30 AM respectively. The tragedy sent shock waves through American culture not felt since the equally public tragedy of the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger in 1986. To be sure, the September 11 terrorist attacks were preceded by other anxiety-producing terrorist events: previous acts such as the 1985 Achille Lauro hijacking and the 1988 terrorist bombing of Pan Am 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland had inspired previous cycles of disaster humor. However, neither the first terrorist bombing at the World Trade Center in 1993 nor the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 had the international impact of the new attacks. -

Delegates Brochure 2020

©ALTTitle Animation Address DM Ltd ‘Monty & Co’ © 2019 Pipkins Productions Limited The Snail and the Whale ©Magic Light Pictures Ltd 2019 Bigmouth Elba Ltd Clangers: © 2019 Coolabi Productions Limited, Smallfilms Limited and Peter Firmin © Tiger Aspect Productions Limited 2019 UK@Kidscreen delegation organised by: 2020 Tuesday 7 July 2020, Sheffield UK The CMC International Exchange is the place to meet UK creatives, producers and service providers. • Broadcasters, co-producers, funders and investors from across the world are welcome to this focused market day. • Meetings take place in one venue on one day (7 July 2020). • Writers, IP developers, producers of TV and digital content, service providers, UK kids’ platforms and distributors are all available to take meetings. • Bespoke Meeting Mojo system is used to upload profiles in advance, present project information and request meetings. • Discover innovative, fresh content, build new partnerships and access the best services and expertise. • Attend the world’s largest conference on kids’ and youth content, 7-9 July 2020 in Sheffield www.thechildrensmediaconference.com • For attendance, please contact [email protected] UK@Kidscreen 2020 3 ContentsTitle Forewords 4-5 Kelebeck Media Nicolette Brent KidsCave Studios Sarah Baynes Kids Industries UK Delegate Companies 6-52 Kids Insights 3Megos KidsKnowBest Acamar Films King Banana TV ALT Animation Lightning Sprite Media Anderson Entertainment LoveLove Films Beyond Kids Bigmouth Audio Lupus Films Cloth Cat Animation Magic Light -

Jackie and Maria Took Longer Than Any of My Other Novels So Far

Dedication For Barbara Douka, who gave me the idea for this novel Epigraph Of all creatures that can feel and think, we women are the worst treated things alive. —EURIPIDES, MEDEA, 431 B.C. Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Act I Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Act II Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Chapter 28 Chapter 29 Chapter 30 Chapter 31 Chapter 32 Chapter 33 Chapter 34 Chapter 35 Chapter 36 Chapter 37 Chapter 38 Chapter 39 Chapter 40 Act III Chapter 41 Chapter 42 Chapter 43 Chapter 44 Chapter 45 Chapter 46 Chapter 47 Chapter 48 Chapter 49 Chapter 50 Chapter 51 Chapter 52 Chapter 53 Chapter 54 Chapter 55 Chapter 56 Chapter 57 Chapter 58 Chapter 59 Chapter 60 Act IV Chapter 61 Chapter 62 Chapter 63 Chapter 64 Chapter 65 Chapter 66 Chapter 67 Chapter 68 Chapter 69 Chapter 70 Act V Chapter 71 Chapter 72 Chapter 73 Chapter 74 Chapter 75 Chapter 76 Chapter 77 Chapter 78 Acknowledgments P.S. Insights, Interviews & More . .* About the Author About the Book Praise Also by Gill Paul Copyright About the Publisher Act I Chapter 1 Hotel Danieli; Venice, Italy September 3, 1957 Come with me.” Maria felt her elbow being tugged by the party’s hostess, so insistently that she almost toppled sideways. “I want to introduce you to your fellow Greeks: Aristotle and Tina Onassis. -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 794 Monday No. 213 26 November 2018 PARLIAMENTARYDEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDEROFBUSINESS Questions Universal Credit .............................................................................................................473 Shipbuilding: Appledore Shipyard..................................................................................475 Verify: Digital Identity System .......................................................................................477 Gender Pay Gap.............................................................................................................480 Russia and Ukraine: Seizure of Naval Vessels Private Notice Question ..................................................................................................482 Stalking Protection Bill First Reading...................................................................................................................485 Parking (Code of Practice) Bill First Reading...................................................................................................................486 Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 (Amendment) Order 2018 Motion to Approve ..........................................................................................................486 Infrastructure Planning (Water Resources) (England) Order 2018 Motion to Approve ..........................................................................................................486 Prisons (Interference with Wireless Telegraphy) Bill Order of Commitment Discharged...................................................................................486 -

Humor, Unlaughter, and Boundary Maintenance Author(S): Moira Smith Source: the Journal of American Folklore, Vol

Humor, Unlaughter, and Boundary Maintenance Author(s): Moira Smith Source: The Journal of American Folklore, Vol. 122, No. 484 (Spring, 2009), pp. 148-171 Published by: University of Illinois Press on behalf of American Folklore Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20487675 Accessed: 13-01-2017 17:24 UTC JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms University of Illinois Press, American Folklore Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of American Folklore This content downloaded from 201.103.83.206 on Fri, 13 Jan 2017 17:24:52 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms MOIRA SMITH Humor, Unlaughter, and Boundary Maintenance Some joke performances are meant to elicit differential responses-laughterfrom some, and unlaughterfrom salient others-and so serve as powerful methods for heightening group boundaries. This article illustrates this thesis by analyzing au dience responses to practical jokes and to the Muhammad cartoons that aroused worldwide controversy in 2006. To further make this case, I will delineate a theo ry of the audience for humor. Such a theory has heretofore been largely missing from both folklore and humor scholarship; instead, the lion's share of scholarly attention has gone to the performers, with the audience's role taken for granted. -

Atomic Spice

Figure 1: Mary in 1951 Atomic Spice Mary Flowers Copyright c 2009 by Mary Flowers This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ or send a letter to Creative Commons, PO Box 1866, Mountain View, CA 94042, USA. iv Editorial note: These memoirs were originally written by Gran/Ma/Mary on some obscure word-processing system during the 1980s. In the absence of any usable electronic copy, we scanned a surviving printed version and did our best { with a lot of help from Mary { to correct and re-format the result. Mary added the postscript in May 2009. Naomi Buneman Peter Buneman Brian Flowers Contents Prologue 1 1 Aliens and Atoms 7 2 The Land of Milk and Honey 17 3 The Birth and the Bomb 29 4 Travels and Tribulations 47 5 A Winter of Discontent 61 6 Friends and Fences 73 7 Harwell and Hamburg 91 8 Domesticity, Doubts and Defectors 107 9 Introspection and Apprehension 121 10 Racialism and Resolution 139 11 Fame and Notoriety 157 12 Stability and Security 173 Epilogue 189 Postscript 199 v List of Figures 1 Frontispiece . ii 6.1 Mary and Oscar, Summer 1947 . 77 6.2 The Harwell prefab in 1947 . 77 6.3 Harwell from the prefab in 1947 . 78 6.4 Mary with Oscar's relatives in Hamburg, May 1947 . 78 11.1 A press cutting from 1952 . 167 11.2 Peter, Mary, Michael and Brian in 1952 . -

Humor, Unlaughter, and Boundary Maintenance

Moira Smith Humor, Unlaughter, and Boundary Maintenance Some joke performances are meant to elicit differential responses—laughter from some, and unlaughter from salient others—and so serve as powerful methods for heightening group boundaries. This article illustrates this thesis by analyzing au- dience responses to practical jokes and to the Muhammad cartoons that aroused worldwide controversy in 2006. To further make this case, I will delineate a theo- ry of the audience for humor. Such a theory has heretofore been largely missing from both folklore and humor scholarship; instead, the lion’s share of scholarly attention has gone to the performers, with the audience’s role taken for granted. In boundary-heightening humor, the audience response is the subject of special attention, and it is interpreted in terms of contemporary notions about the impor- tance of having a sense of humor and especially of being able to laugh at oneself. Jokes and humor have attracted a fair amount of serious attention by folklorists, but outside of our field these topics are often easily dismissed as trivial and insignificant. However, in January and February of 2006, a series of cartoons published in a Dan- ish newspaper sparked an enormous international furor that was anything but in- consequential. Diplomats were recalled and Danish products were boycotted in sev- eral countries. Thousands demonstrated in protests around the globe, some of which turned into violent riots that left buildings burned and protestors dead and injured. If ever we needed proof that humor is not a trivial matter, this grim series of events was it. -

Warwick.Ac.Uk/Lib-Publications COPYRIGHT

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/104996/ Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications COPYRIGHT Reproduction of this thesis, other than as permitted under the United Kingdom Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under specific agreement with the copyright holder, is prohibited. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. REPRODUCTION QUALITY NOTICE The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the original thesis. Whilst every effort has been made to ensure the highest quality of reproduction, some pages which contain small or poor printing may not reproduce well. Previously copyrighted material Qournal articles, published texts etc.) is not reproduced. THIS THESIS HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED 3 Towards a Creative Aesthetics - W ith Reference to Bergson Coryn Russell Ronald Smethurst B .A. Hons., M.A. This Work is Submitted for the Qualification of PhD To the University of Warwick Research conducted in The Department of Philosophy Submitted: