Atomic Spice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons 1926 to Circa 1990

A History of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons 1926 to circa 1990 TT King TT King A History of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons, 1926 to circa 1990 TT King Society Archivist 1 A History of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons, 1926 to circa 1990 © 2017 The Society of British Neurological Surgeons First edition printed in 2017 in the United Kingdom. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval sys- tem or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permis- sion of The Society of British Neurological Surgeons. While every effort has been made to ensure the accuracy of the infor- mation contained in this publication, no guarantee can be given that all errors and omissions have been excluded. No responsibility for loss oc- casioned to any person acting or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by The Society of British Neurological Surgeons or the author. Published by The Society of British Neurological Surgeons 35–43 Lincoln’s Inn Fields London WC2A 3PE www.sbns.org.uk Printed in the United Kingdom by Latimer Trend EDIT, DESIGN AND TYPESET Polymath Publishing www.polymathpubs.co.uk 2 The author wishes to express his gratitude to Philip van Hille and Matthew Whitaker of Polymath Publishing for bringing this to publication and to the British Orthopaedic Association for their help. 3 A History of the Society of British Neurological Surgeons 4 Contents Foreword -

APA Newsletter on Philosophy and Computers, Vol. 18, No. 2 (Spring

NEWSLETTER | The American Philosophical Association Philosophy and Computers SPRING 2019 VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 2 FEATURED ARTICLE Jack Copeland and Diane Proudfoot Turing’s Mystery Machine ARTICLES Igor Aleksander Systems with “Subjective Feelings”: The Logic of Conscious Machines Magnus Johnsson Conscious Machine Perception Stefan Lorenz Sorgner Transhumanism: The Best Minds of Our Generation Are Needed for Shaping Our Future PHILOSOPHICAL CARTOON Riccardo Manzotti What and Where Are Colors? COMMITTEE NOTES Marcello Guarini Note from the Chair Peter Boltuc Note from the Editor Adam Briggle, Sky Croeser, Shannon Vallor, D. E. Wittkower A New Direction in Supporting Scholarship on Philosophy and Computers: The Journal of Sociotechnical Critique CALL FOR PAPERS VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 2 SPRING 2019 © 2019 BY THE AMERICAN PHILOSOPHICAL ASSOCIATION ISSN 2155-9708 APA NEWSLETTER ON Philosophy and Computers PETER BOLTUC, EDITOR VOLUME 18 | NUMBER 2 | SPRING 2019 Polanyi’s? A machine that—although “quite a simple” one— FEATURED ARTICLE thwarted attempts to analyze it? Turing’s Mystery Machine A “SIMPLE MACHINE” Turing again mentioned a simple machine with an Jack Copeland and Diane Proudfoot undiscoverable program in his 1950 article “Computing UNIVERSITY OF CANTERBURY, CHRISTCHURCH, NZ Machinery and Intelligence” (published in Mind). He was arguing against the proposition that “given a discrete- state machine it should certainly be possible to discover ABSTRACT by observation sufficient about it to predict its future This is a detective story. The starting-point is a philosophical behaviour, and this within a reasonable time, say a thousand discussion in 1949, where Alan Turing mentioned a machine years.”3 This “does not seem to be the case,” he said, and whose program, he said, would in practice be “impossible he went on to describe a counterexample: to find.” Turing used his unbreakable machine example to defeat an argument against the possibility of artificial I have set up on the Manchester computer a small intelligence. -

Births, Marriages, and Deaths

DEC. 31, 1955 MEDICAL NEWS MEDICALBRrsIJOURNAL. 1631 Lead Glazes.-For some years now the pottery industry British Journal of Ophthalmology.-The new issue (Vol. 19, has been forbidden to use any but leadless or "low- No. 12) is now available. The contents include: solubility" glazes, because of the risk of lead poisoning. EXPERIENCE IN CLINIcAL EXAMINATION OP CORNEAL SENsITiVrry. CORNEAL SENSITIVITY AND THE NASO-LACRIMAL REFLEX AFTER RETROBULBAR However, in some teaching establishments raw lead glazes or ANAES rHESIA. Jorn Boberg-Ans. glazes containing a high percentage of soluble lead are still UVEITIS. A CLINICAL AND STATISTICAL SURVEY. George Bennett. INVESTIGATION OF THE CARBONIC ANHYDRASE CONTENT OF THE CORNEA OF used. The Ministry of Education has now issued a memo- THE RABBIT. J. Gloster. randum to local education authorities and school governors HYALURONIDASE IN OCULAR TISSUES. I. SENSITIVE BIOLOGICAL ASSAY FOR SMALL CONCENTRATIONS OF HYALURONIDASE. CT. Mayer. (No. 517, dated November 9, 1955) with the object of INCLUSION BODIES IN TRACHOMA. A. J. Dark. restricting the use of raw lead glazes in such schools. The TETRACYCLINE IN TRACHOMA. L. P. Agarwal and S. R. K. Malik. APPL IANCES: SIMPLE PUPILLOMETER. A. Arnaud Reid. memorandum also includes a list of precautions to be ob- LARGE CONCAVE MIRROR FOR INDIRECT OPHTHALMOSCOPY. H. Neame. served when handling potentially dangerous glazes. Issued monthly; annual subscription £4 4s.; single copy Awards for Research on Ageing.-Candidates wishing to 8s. 6d.; obtainable from the Publishing Manager, B.M.A. House, enter for the 1955-6 Ciba Foundation Awards for research Tavistock Square, London, W.C.1. -

I V Anthropomorphic Attachments in U.S. Literature, Robotics, And

Anthropomorphic Attachments in U.S. Literature, Robotics, and Artificial Intelligence by Jennifer S. Rhee Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kenneth Surin, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Michael Hardt ___________________________ Katherine Hayles ___________________________ Timothy Lenoir Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 i v ABSTRACT Anthropomorphic Attachments in U.S. Literature, Robotics, and Artificial Intelligence by Jennifer S. Rhee Program in Literature Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Kenneth Surin, Supervisor ___________________________ Mark Hansen ___________________________ Michael Hardt ___________________________ Katherine Hayles ___________________________ Timothy Lenoir An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Literature in the Graduate School of Duke University 2010 Copyright by Jennifer S. Rhee 2010 Abstract “Anthropomorphic Attachments” undertakes an examination of the human as a highly nebulous, fluid, multiple, and often contradictory concept, one that cannot be approached directly or in isolation, but only in its constitutive relationality with the world. Rather than trying to find a way outside of the dualism between human and not- human, -

Becoming a Translator Second Edition

Becoming a Translator Second Edition "Absolutely up-to-date and state of the art in the practical as well as theoretical aspect of translation, this new edition of Becoming a Translator retains the strength of the first edition while offering new sections on current issues. Bright, lively and witty, the book is filled with entertaining and thoughtful examples; I would recommend it to teachers offering courses to beginning and advanced students, and to any translator who wishes to know where the field is today." Malcolm Hayward, Indiana University of Pennsylvania, USA "A very useful book ... I would recommend it to students who aim at a career in translation as a valuable introduction to the profession and an initiation into the social and transactional skills which it requires." Mike Routledge, Royal Holloway, University of London, UK Fusing theory with advice and information about the practicalities of translating, Becoming a Translator is the essential resource for novice and practising translators. The book explains how the market works, helps translators learn how to translate faster and more accurately, as well as providing invaluable advice and tips about how to deal with potential problems such as stress. The second edition has been revised and updated throughout, offering: • a "useful contacts" section • new exercises and examples • new e-mail exchanges to show how translators have dealt with a range of real problems • updated further reading sections • extensive up-to-date information about new translation technologies. Offering suggestions for discussion, activities, and hints for the teaching of translation, the second edition of Becoming a Translator remains invaluable for students on and teachers of courses in translation, as well as for professional translators and scholars of translation and language. -

Parliamentary Debates House of Commons Official Report General Committees

PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT GENERAL COMMITTEES Public Bill Committee FINANCE BILL (Except clauses 1, 5 to 7, 11, 72 to 74 and 112, schedule 1, and certain new clauses and new schedules) Eleventh Sitting Tuesday 10 June 2014 (Afternoon) CONTENTS Programme order amended. CLAUSES 90 to 93 agreed to. SCHEDULE 16 agreed to. CLAUSES 94 and 95 agreed to. SCHEDULE 17 agreed to. CLAUSES 96 to 100 agreed to. SCHEDULE 18 agreed to. CLAUSES 101 to 106 agreed to. SCHEDULE 19 agreed to. CLAUSES 107 and 108 agreed to. SCHEDULE 20 agreed to. CLAUSES 109 and 110 agreed to. SCHEDULE 21 agreed to. CLAUSES 111 and 113 agreed to. SCHEDULE 22 agreed to. CLAUSES 114 to 117 agreed to. Adjourned till Thursday 12 June at Two o’clock. Written evidence reported to the House. PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY OF THE HOUSE OF COMMONS LONDON – THE STATIONERY OFFICE LIMITED £6·00 PBC (Bill 190) 2014 - 2015 Members who wish to have copies of the Official Report of Proceedings in General Committees sent to them are requested to give notice to that effect at the Vote Office. No proofs can be supplied. Corrigenda slips may be published with Bound Volume editions. Corrigenda that Members suggest should be clearly marked in a copy of the report—not telephoned—and must be received in the Editor’s Room, House of Commons, not later than Saturday 14 June 2014 STRICT ADHERENCE TO THIS ARRANGEMENT WILL GREATLY FACILITATE THE PROMPT PUBLICATION OF THE BOUND VOLUMES OF PROCEEDINGS IN GENERAL COMMITTEES © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2014 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. -

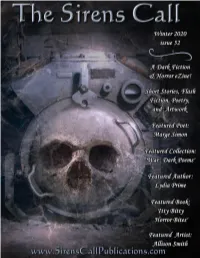

The Sirens Call Ezine Throughout the Years

1 Table of Contents pg. 04 - The Cave| H.B. Diaz pg. 110 - Mud Baby | Lori R. Lopez pg. 07 - Honeysuckle | T.S. Woolard pg. 112 - On Eternity’s Brink | Lori R. Lopez pg. 08 - Return to Chaos | B. T. Petro pg. 115 - Sins for the Father | Marcus Cook pg. 08 - Deathwatch | B. T. Petro pg. 118 - The Island | Brian Rosenberger pg. 09 - A Cup of Holiday Cheer | KC Grifant pg. 120 - Old John | Jeffrey Durkin pg. 12 - Getting Ahead | Kevin Gooden pg. 123 - Case File | Pete FourWinds pg. 14 - Soup for Mother | Sharon Hajj pg. 124 - Filling in a Hole | Radar DeBoard pg. 15 - A Dying Moment | Gavin Gardiner pg. 126 - Butterfly | Lee Greenaway pg. 17 - Snake | Natasha Sinclair pg. 130 - Death’s Gift | Naching T. Kassa pg. 19 - The Cold Death | Nicole Henning pg. 132 - Waste Not | Evan Baughfman pg. 21 - The Burning Bush | O. D. Hegre pg. 132 - Rainbows and Unicorns | Evan Baughfman pg. 24 - The Wishbone | Eileen Taylor pg. 133 - Salty Air | Sonora Taylor pg. 27 - Down by the River Walk | Matt Scott pg. 134 - Death is Interesting | Radar DeBoard pg. 30 - The Reverend I Milkana N. Mingels pg. 134 - It Wasn’t Time | Radar DeBoard pg. 31 - Until Death Do Us Part | Candace Meredith pg. 136 - Future Fuck | Matt Martinek pg. 33 - A Grand Estate | Zack Kullis pg. 139 - The Little Church | Eduard Schmidt-Zorner pg. 36 - The Chase | Siren Knight pg. 140 - Sweet Partings | O. D. Hegre pg. 38 - Darla | Miracle Austin pg. 142 - Christmas Eve on the Rudolph Express | Sheri White pg. 39 - I Remember You | Judson Michael Agla pg. -

British Medical Journal

SUPPLEMENT TO THE BRITISH MEDICAL JOURNAL LONDON: SATURDAY, APRIL 11th, 1936 CONTENTS PACE PAGE CORRESPONDENCE: BRITISH MEDICAL ASSOCIATION CAPITATION FEE FOR PERSONS RESTORED TO BENEFIT. ... 146 Annual Meeting, Oxford, July, 1936: THE PROBLEM OF THE OUT-PATIENT ... ... ... ... 146 ORDER OFBEss ... ... ... ... ... 137 NAVAL, MILITARY, AND AIR FORCE APPOINTMENTS... 146 SCIENTIFIC SECTIONS ... 138 ASSOCIATION NOTICES: ... ... ... PROVISIONAL TImE-TABLE ... ... ... 141 TABLE OF OFFICIAL DATES. ... ... 147 COLLEGE, HOTEL, AND BOARDING HOUSE ACCOMMODATION ... 142 BRANCH AND DIVISION MIEETINGS TO BE HELD ...... 147 INSURANCE MEDICAL SERVICE WEEK BY WEEK .-.. 144 ASSOCIATION INTELLIGENCE AND DIARY .... ... 147 RECEPTION TO GLASGOW MEDICAL STUDENTS. ... 145 DIARY OF SOCIETIES AND LECTURES ...... 147 CURRENT NOTES: VACANCIES AND APPOINTMENTS. ...... 148 TREASURER'S CuP GOLF COMPEIITION ... ... ... ... 146 BIRTHS, MARRIAGES, AND DEATHS ... ... ... ... 148 British Medical Association ONE HUNDRED AND FOURTH ANNUAL MEETING, OXFORD, JULY, 1936 Patron His MAJESTY THE KING President: SIR JAMES BARRETT, K.B.E., C.B., C.M.G., LL.D., M.D., M.S., F.R.C.S., Deputy Chancellor of Melbourne University. President-Elect: SIR E. FARQUHAR BUZZARD, Bt., R.C.V.O., LL.D., D.M., F.R.C.P., Regius Professor of Medicine in the University of Oxford. Chairman of Representative Body: H. S. SOUTrTAR, C.B.E., M.D., M.Ch., F.R.C.S. Chairman of Council: E. KAYE LE FLEMING, M.A., M.D. Treasurer: N. BISHOP HARMAN, LL.D., F.R.C.S. PROVISIONAL PROGRAMME The Annual Representative Meeting will begin at the functions confined to ladies, will be at Rhodes House, Town Hall on Friday, July 17th,-at 9.30 a.m., and be South Parks Road. -

Low Resolution Pictures

Low resolution pictures highfieldsoffice.wordpress.com BlogBook 2 ©2016 highfieldsoffice.wordpress.com Contents 1 2013 13 1.1 January .......................................... 14 1.1.1 It’s January 2013 & The ”Highfields Curfew” Is Still In Place! (2013-01-04 18:37) 15 1.1.2 New Updates On Mahdi Hashi (Daily Mail) & Leicester’s Thurnby Lodge Drama (Leicester Mercury) (2013-01-06 11:21) ..................... 18 1.1.3 Looking Into The Future of Voting Behaviour in UK: What Might Happen When The British-Minorities Voters Grow? (2013-01-07 16:29) . 25 1.1.4 The Independent: How The British MI5 Coerce British-Somalis to Spy On Their Own Communities (2013-01-07 18:47) ...................... 30 1.1.5 For Your Self-Enlightement: Articles From This Week Newspapers (2013-01-11 12:50) ................................ 35 1.1.6 Spinney Hills LPU: A Militarized Police Station Inside The ”Local Terrorists Hotbed”!!!!! (2013-01-12 16:17) ......................... 37 1.1.7 Glenn Greenwald (The Guardian): In 4-Years, The West Have Bombed & Invaded 8 Muslim Nations (Is This not a ’War on Islam’?, he asks) (2013-01-15 11:48) . 39 1.1.8 St.Phillips Centre: Your ”Friendly” Inter-Faith Society or A Church/Diocese With A Secret? (Doubling as a Counter-Terrorism & ”Re-Education” Centre) (2013-01-19 10:29) ................................ 46 1.1.9 The Daily Mail’s First Exclusive Interview With Mahdi Hashi in The New York Jail: The Torture in Djibouti Ordeal In the Hands of CIA (with British Government ”Acquiescence”) (2013-01-20 10:36) ....................... 49 1.1.10 Important Additional Information for Muslims & Counter-Terrorism (and those in Leicester on FMO) and A Great Reading Collection from Public Intelligence (2013-01-20 19:11) ............................... -

Newfolk Ndif: Making a Big Apple Crumble...Chapter 1

Newfolk NDiF: Making a Big Apple Crumble...Chapter 1 New Directions in Folklore 6 June 2002 Newfolk :: NDiF :: Issue 6 :: Chapter 1 :: Page 1:: Page 2 :: Chapter 2 :: References Making a Big Apple Crumble: The Role of Humor in Constructing a Global Response to Disaster1 Bill Ellis Chapter One: Introduction On the morning of September 11, 2001, terrorists associated with Osama bin Laden's al-Qaida, a fundamentalist Islamic political movement, hijacked four American jetliners. Two were crashed into the twin towers of New York's World Trade Center, causing them to collapse with catastrophic loss of life. A third was crashed into the Pentagon, costing an additional 189 lives, while passengers on a fourth evidently attacked the hijackers, causing the plane to crash in a rural area in western Pennsylvania with the loss of all 44 persons aboard. Much of the drama was played out live on national television, including the crash of the second plane into the South Tower at 9:03 AM and both towers' collapse, at 10:05 and 10:30 AM respectively. The tragedy sent shock waves through American culture not felt since the equally public tragedy of the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger in 1986. To be sure, the September 11 terrorist attacks were preceded by other anxiety-producing terrorist events: previous acts such as the 1985 Achille Lauro hijacking and the 1988 terrorist bombing of Pan Am 103 over Lockerbie, Scotland had inspired previous cycles of disaster humor. However, neither the first terrorist bombing at the World Trade Center in 1993 nor the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 had the international impact of the new attacks. -

Can Machines Think? the Controversy That Led to the Turing Test, 1946-1950

Can machines think? The controversy that led to the Turing test, 1946-1950 Bernardo Gonçalves1 Abstract Turing’s much debated test has turned 70 and is still fairly controversial. His 1950 paper is seen as a complex and multi-layered text and key questions remain largely unanswered. Why did Turing choose learning from experience as best approach to achieve machine intelligence? Why did he spend several years working with chess-playing as a task to illustrate and test for machine intelligence only to trade it off for conversational question-answering later in 1950? Why did Turing refer to gender imitation in a test for machine intelligence? In this article I shall address these questions directly by unveiling social, historical and epistemological roots of the so-called Turing test. I will draw attention to a historical fact that has been scarcely observed in the secondary literature so far, namely, that Turing's 1950 test came out of a controversy over the cognitive capabilities of digital computers, most notably with physicist and computer pioneer Douglas Hartree, chemist and philosopher Michael Polanyi, and neurosurgeon Geoffrey Jefferson. Seen from its historical context, Turing’s 1950 paper can be understood as essentially a reply to a series of challenges posed to him by these thinkers against his view that machines can think. Keywords: Alan Turing, Can machines think?, The imitation game, The Turing test, Mind-machine controversy, History of artificial intelligence. Robin Gandy (1919-1995) was one of Turing’s best friends and his only doctorate student. He received Turing’s mathematical books and papers when Turing died in 1954, and took over from Max Newman in 1963 the task of editing the papers for publication.1 Regarding Turing’s purpose in writing his 1950 paper and sending it for publication, Gandy offered a testimony previously brought forth by Jack Copeland which has not yet been commented about:2 It was intended not so much as a penetrating contribution to philosophy but as propaganda. -

Memories of Hugh Cairns* by Sir Geoffrey Jefferson

J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.22.3.155 on 1 August 1959. Downloaded from J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiat., 1959, 22, 155. MEMORIES OF HUGH CAIRNS* BY SIR GEOFFREY JEFFERSON Hugh Cairns was born at Port Pirie in South whom all went for advice, She had natural talents Australia on June 26, 1896. That is the starting and a zest for life; she was one to whom everyone in point, but some enrichment should come from a the village went with their troubles. Perhaps from sketch of his early days and his Australian back- her he inherited his love of music, which she taught, ground. To be born of sound, if humble, stock but there was also his father with his violin playing. under the high and wide Australian skies is as Hugh inherited something else from his father, a fine a beginning as a perfectionist trait in man could desire. His manual skills. The father, William Cairns, son was fortunate to threatened with tuber- have fused into his culosis, had sailed out character so much of from Scotland on medi- the best qualities of guest. Protected by copyright. cal advice. At Port his parents. I have had Pirie he had found the pleasure of visiting work in timber con- Riverton, a quiet place struction for the load- indeed, basking and ing of ships, for this often baking in the was the port of ship- brilliant sun and heat ment from the smelting of South Australia. I plant of the great saw the little primary Broken Hill Proprie- school and met, by tory, Australia's chief request, two or three up-country mining area people who had been and today its largest Hugh's school fellows.