Criminal Law in Cyberspace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Grand Theft Archive': a Quantitative Analysis of the State of Computer

Gooding, P. and Terras, M. (2008) "„Grand Theft Archive‟: a quantitative analysis of the current state of computer game preservation". The International Journal of Digital Curation. Issue 2, Volume 3, 2008. http://www.ijdc.net/ijdc/article/view/85/90 1 ‘Grand Theft Archive’: A Quantitative Analysis of the Current State of Computer Game Preservation Paul Gooding, Librarian, BBC Sports Library, London Melissa Terras, School of Library, Archive and Information Studies, University College London November 2008 Abstract Computer games, like other digital media, are extremely vulnerable to long-term loss, yet little work has been done to preserve them. As a result we are experiencing large-scale loss of the early years of gaming history. Computer games are an important part of modern popular culture, and yet are afforded little of the respect bestowed upon established media such as books, film, television and music. We must understand the reasons for the current lack of computer game preservation in order to devise strategies for the future. Computer game history is a difficult area to work in, because it is impossible to know what has been lost already, and early records are often incomplete. This paper uses the information that is available to analyse the current status of computer game preservation, specifically in the UK. It makes a quantitative analysis of the preservation status of computer games, and finds that games are already in a vulnerable state. It proposes that work should be done to compile accurate metadata on computer games and to analyse more closely the exact scale of data loss, while suggesting strategies to overcome the barriers that currently exist. -

Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: an Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers Thomas Jeffrey Holt University of Missouri-St

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Missouri, St. Louis University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 11-22-2005 Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: An Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers Thomas Jeffrey Holt University of Missouri-St. Louis, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Holt, Thomas Jeffrey, "Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: An Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers" (2005). Dissertations. 616. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/616 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hacks, Cracks, and Crime: An Examination of the Subculture and Social Organization of Computer Hackers by THOMAS J. HOLT M.A., Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Missouri- St. Louis, 2003 B.A., Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Missouri- St. Louis, 2000 A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Graduate School of the UNIVERSITY OF MISSOURI- ST. LOUIS In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Criminology and Criminal Justice August, 2005 Advisory Committee Jody Miller, Ph. D. Chairperson Scott H. Decker, Ph. D. G. David Curry, Ph. D. Vicki Sauter, Ph. D. Copyright 2005 by Thomas Jeffrey Holt All Rights Reserved Holt, Thomas, 2005, UMSL, p. -

Ethical Hacking

International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, Volume 5, Issue 6, June 2015 1 ISSN 2250-3153 Ethical Hacking Susidharthaka Satapathy , Dr.Rasmi Ranjan Patra CSA, CPGS, OUAT, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India Abstract- In today's world where the information damaged the target system nor steal the information, they communication technique has brought the world together there is evaluate target system security and report back to the owner one of the increase growing areas is security of network ,which about the threats found. certainly generate discussion of ETHICAL HACKING . The main reason behind the discussion of ethical hacking is insecurity of the network i.e. hacking. The need of ethical hacking is to IV. FATHER OF HACKING protect the system from the damage caused by the hackers. The In 1971, John Draper , aka captain crunch, was one of the main reason behind the study of ethical hacking is to evaluate best known early phone hacker & one of the few who can be target system security & report back to owner. This paper helps called one of the father's of hacking. to generate a brief idea of ethical hacking & all its aspects. Index Terms- Hacker, security, firewall, automated, hacked, V. IS HACKING NECESSARY crackers Hacking is not what we think , It is an art of exploring the threats in a system . Today it sounds something with negative I. INTRODUCTION shade , but it is not exactly that many professionals hack system so as to learn the deficiencies in them and to overcome from it he increasingly growth of internet has given an entrance and try to improve the system security. -

Paradise Lost , Book III, Line 18

_Paradise Lost_, book III, line 18 %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% ++++++++++Hacker's Encyclopedia++++++++ ===========by Logik Bomb (FOA)======== <http://www.xmission.com/~ryder/hack.html> ---------------(1997- Revised Second Edition)-------- ##################V2.5################## %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% "[W]atch where you go once you have entered here, and to whom you turn! Do not be misled by that wide and easy passage!" And my Guide [said] to him: "That is not your concern; it is his fate to enter every door. This has been willed where what is willed must be, and is not yours to question. Say no more." -Dante Alighieri _The Inferno_, 1321 Translated by John Ciardi Acknowledgments ---------------------------- Dedicated to all those who disseminate information, forbidden or otherwise. Also, I should note that a few of these entries are taken from "A Complete List of Hacker Slang and Other Things," Version 1C, by Casual, Bloodwing and Crusader; this doc started out as an unofficial update. However, I've updated, altered, expanded, re-written and otherwise torn apart the original document, so I'd be surprised if you could find any vestiges of the original file left. I think the list is very informative; it came out in 1990, though, which makes it somewhat outdated. I also got a lot of information from the works listed in my bibliography, (it's at the end, after all the quotes) as well as many miscellaneous back issues of such e-zines as _Cheap Truth _, _40Hex_, the _LOD/H Technical Journals_ and _Phrack Magazine_; and print magazines such as _Internet Underground_, _Macworld_, _Mondo 2000_, _Newsweek_, _2600: The Hacker Quarterly_, _U.S. News & World Report_, _Time_, and _Wired_; in addition to various people I've consulted. -

Hot Sounds of Summer Concert Lineup Is Hot!

PUBLIC INFORMATION OFFICE Sally Ellertson Public Information Officer 141 West Renfro Burleson, Texas 76028-4261 February 10, 2015 817-426-9622 F: 817-426-9390 [email protected] www.burlesontx.com It’s going to be a hot Hot Sounds of Summer concert series in 2015, starting with sophomore sensation Reagan James, best known for making it to the Top 10 on NBC’s “The Voice” headlining on May 29, and ending with crowd favorite Le Freak, bringing disco back to Burleson, on June 26. J.D. Monson, country/classic rock, is the headliner June 5. Journey fans don’t want to miss ESCAPE on June 12, and a 2014 favorite, Buddy Whittington, is bringing back the blues on June 19. The Hot Sounds of Summer showcases free 90-minute concerts that start at 7:30 p.m., every Friday between May 29 and June 26, at the intersection of Ellison and Wilson streets (124 W. Ellison St.). Between 4 p.m. and 10 p.m., Ellison Street is closed at Main Street and at Warren Street and Wilson is closed at the side entrance to city hall and at Wood Shopping Center. Come down early and eat at one of the more than half a dozen Old Town restaurants, then set up your lawn chairs and blankets in the street for the concert. Food and drink are allowed at the concerts, but patrons are strongly discouraged from bringing glass bottles, due to safety reasons. The 16-year-old James, a sophomore at Burleson’s Centennial High School, is an R&B/pop artist. -

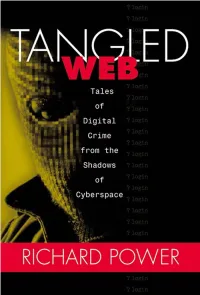

Tangled Web : Tales of Digital Crime from the Shadows of Cyberspace

TANGLED WEB Tales of Digital Crime from the Shadows of Cyberspace RICHARD POWER A Division of Macmillan USA 201 West 103rd Street, Indianapolis, Indiana 46290 Tangled Web: Tales of Digital Crime Associate Publisher from the Shadows of Cyberspace Tracy Dunkelberger Copyright 2000 by Que Corporation Acquisitions Editor All rights reserved. No part of this book shall be reproduced, stored in a Kathryn Purdum retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, pho- Development Editor tocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the Hugh Vandivier publisher. No patent liability is assumed with respect to the use of the infor- mation contained herein. Although every precaution has been taken in the Managing Editor preparation of this book, the publisher and author assume no responsibility Thomas Hayes for errors or omissions. Nor is any liability assumed for damages resulting from the use of the information contained herein. Project Editor International Standard Book Number: 0-7897-2443-x Tonya Simpson Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 00-106209 Copy Editor Printed in the United States of America Michael Dietsch First Printing: September 2000 Indexer 02 01 00 4 3 2 Erika Millen Trademarks Proofreader Benjamin Berg All terms mentioned in this book that are known to be trademarks or ser- vice marks have been appropriately capitalized. Que Corporation cannot Team Coordinator attest to the accuracy of this information. Use of a term in this book should Vicki Harding not be regarded as affecting the validity of any trademark or service mark. Design Manager Warning and Disclaimer Sandra Schroeder Every effort has been made to make this book as complete and as accurate Cover Designer as possible, but no warranty or fitness is implied. -

Journey Don't Stop Believin' / the Journey Story (An Audio Biography) Mp3, Flac, Wma

Journey Don't Stop Believin' / The Journey Story (An Audio Biography) mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Non Music Album: Don't Stop Believin' / The Journey Story (An Audio Biography) Country: UK Released: 1982 Style: Pop Rock, Spoken Word, Classic Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1303 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1911 mb WMA version RAR size: 1118 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 412 Other Formats: MOD MP4 MP1 AAC MIDI TTA XM Tracklist Hide Credits Don't Stop Believin' A Producer – Kevin Elson, Mike StoneWritten-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. 4:08 Perry* The Journey Story (An Audio Biography) In The Morning B1 Written-By – G. Rolie*, R. Valory* To Play Some Music B2 Written-By – G. Rolie*, N. Schon* Saturday Nite B3 Written-By – Gregg Rolie Wheel In The Sky B4 Written-By – D. Valory*, Schon*, Fleischman* Feeling That Way B5 Written-By – Dunbar*, Rolie*, Perry* Anytime B6 Written-By – Rolie*, N. Schon*, Fleischman*, Silver*, R. Valory* Lovin' Touchin' Squeezin' B7 Written-By – S. Perry* When You're Alone (It Ain't Easy) B8 Written-By – N. Schon*, S. Perry* Someday Soon B9 Written-By – G. Rolie*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Any Way You Want It B10 Written-By – N. Schon*, S. Perry* Stone In Love B11 Written-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Who's Crying Now B12 Written-By – J. Cain*, S. Perry* Mother Father B13 Written-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Don't Stop Believin' B14 Written-By – J. Cain*, N. Schon*, S. Perry* Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – CBS Records Copyright (c) – CBS Records Pressed By – Orlake Records Published By – Screen Gems-EMI Music Ltd. -

A Zahlensysteme

A Zahlensysteme Außer dem Dezimalsystem sind das Dual-,dasOktal- und das Hexadezimalsystem gebräuchlich. Ferner spielt das Binär codierte Dezimalsystem (BCD) bei manchen Anwendungen eine Rolle. Bei diesem sind die einzelnen Dezimalstellen für sich dual dargestellt. Die folgende Tabelle enthält die Werte von 0 bis dezimal 255. Be- quemlichkeitshalber sind auch die zugeordneten ASCII-Zeichen aufgeführt. dezimal dual oktal hex BCD ASCII 0 0 0 0 0 nul 11111soh 2102210stx 3113311etx 4 100 4 4 100 eot 5 101 5 5 101 enq 6 110 6 6 110 ack 7 111 7 7 111 bel 8 1000 10 8 1000 bs 9 1001 11 9 1001 ht 10 1010 12 a 1.0 lf 11 101 13 b 1.1 vt 12 1100 14 c 1.10 ff 13 1101 15 d 1.11 cr 14 1110 16 e 1.100 so 15 1111 17 f 1.101 si 16 10000 20 10 1.110 dle 17 10001 21 11 1.111 dc1 18 10010 22 12 1.1000 dc2 19 10011 23 13 1.1001 dc3 20 10100 24 14 10.0 dc4 21 10101 25 15 10.1 nak 22 10110 26 16 10.10 syn 430 A Zahlensysteme 23 10111 27 17 10.11 etb 24 11000 30 18 10.100 can 25 11001 31 19 10.101 em 26 11010 32 1a 10.110 sub 27 11011 33 1b 10.111 esc 28 11100 34 1c 10.1000 fs 29 11101 35 1d 10.1001 gs 30 11110 36 1e 11.0 rs 31 11111 37 1f 11.1 us 32 100000 40 20 11.10 space 33 100001 41 21 11.11 ! 34 100010 42 22 11.100 ” 35 100011 43 23 11.101 # 36 100100 44 24 11.110 $ 37 100101 45 25 11.111 % 38 100110 46 26 11.1000 & 39 100111 47 27 11.1001 ’ 40 101000 50 28 100.0 ( 41 101001 51 29 100.1 ) 42 101010 52 2a 100.10 * 43 101011 53 2b 100.11 + 44 101100 54 2c 100.100 , 45 101101 55 2d 100.101 - 46 101110 56 2e 100.110 . -

Newagearcade.Com 5000 in One Arcade Game List!

Newagearcade.com 5,000 In One arcade game list! 1. AAE|Armor Attack 2. AAE|Asteroids Deluxe 3. AAE|Asteroids 4. AAE|Barrier 5. AAE|Boxing Bugs 6. AAE|Black Widow 7. AAE|Battle Zone 8. AAE|Demon 9. AAE|Eliminator 10. AAE|Gravitar 11. AAE|Lunar Lander 12. AAE|Lunar Battle 13. AAE|Meteorites 14. AAE|Major Havoc 15. AAE|Omega Race 16. AAE|Quantum 17. AAE|Red Baron 18. AAE|Ripoff 19. AAE|Solar Quest 20. AAE|Space Duel 21. AAE|Space Wars 22. AAE|Space Fury 23. AAE|Speed Freak 24. AAE|Star Castle 25. AAE|Star Hawk 26. AAE|Star Trek 27. AAE|Star Wars 28. AAE|Sundance 29. AAE|Tac/Scan 30. AAE|Tailgunner 31. AAE|Tempest 32. AAE|Warrior 33. AAE|Vector Breakout 34. AAE|Vortex 35. AAE|War of the Worlds 36. AAE|Zektor 37. Classic Arcades|'88 Games 38. Classic Arcades|1 on 1 Government (Japan) 39. Classic Arcades|10-Yard Fight (World, set 1) 40. Classic Arcades|1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally (94/07/18) 41. Classic Arcades|18 Holes Pro Golf (set 1) 42. Classic Arcades|1941: Counter Attack (World 900227) 43. Classic Arcades|1942 (Revision B) 44. Classic Arcades|1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) 45. Classic Arcades|1943: The Battle of Midway (Euro) 46. Classic Arcades|1944: The Loop Master (USA 000620) 47. Classic Arcades|1945k III 48. Classic Arcades|19XX: The War Against Destiny (USA 951207) 49. Classic Arcades|2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge (rev 1.21) 50. Classic Arcades|2020 Super Baseball (set 1) 51. -

Flexible Infections: Computer Viruses, Human Bodies, Nation-States, Evolutionary Capitalism

Science,Helmreich Technology, / Flexible Infections& Human Values Flexible Infections: Computer Viruses, Human Bodies, Nation-States, Evolutionary Capitalism Stefan Helmreich New York University This article analyzes computer security rhetoric, particularly in the United States, argu- ing that dominant cultural understandings of immunology, sexuality, legality, citizen- ship, and capitalism powerfully shape the way computer viruses are construed and com- bated. Drawing on popular and technical handbooks, articles, and Web sites, as well as on e-mail interviews with security professionals, the author explores how discussions of computer viruses lean on analogies from immunology and in the process often encode popular anxieties about AIDS. Computer security rhetoric about compromised networks also uses language reminiscent of that used to describe the “bodies” of nation-states under military threat from without and within. Such language portrays viruses using images of foreignness, illegality, and otherness. The security response to viruses advo- cates the virtues of the flexible and adaptive response—a rhetoric that depends on evolu- tionary language but also on the ideological idiom of advanced capitalism. As networked computing becomes increasingly essential to the operations of corporations, banks, government, the military, and academia, worries about computer security and about computer viruses are intensifying among the people who manage and use these networks. The end of the 1990s saw the emergence of a small industry dedicated to antivirus protection software, and one can now find on the World Wide Web a great deal of information about how viruses work, how they can be combated, and how computer users might keep up with ever-changing inventories and taxonomies of the latest viruses. -

The Internet Is a Semicommons

GRIMMELMANN_10_04_29_APPROVED_PAGINATED 4/29/2010 11:26 PM THE INTERNET IS A SEMICOMMONS James Grimmelmann* I. INTRODUCTION As my contribution to this Symposium on David Post’s In Search of Jefferson’s Moose1 and Jonathan Zittrain’s The Future of the Internet,2 I’d like to take up a question with which both books are obsessed: what makes the Internet work? Post’s answer is that the Internet is uniquely Jeffersonian; it embodies a civic ideal of bottom-up democracy3 and an intellectual ideal of generous curiosity.4 Zittrain’s answer is that the Internet is uniquely generative; it enables its users to experiment with new uses and then share their innovations with each other.5 Both books tell a story about how the combination of individual freedom and a cooperative ethos have driven the Internet’s astonishing growth. In that spirit, I’d like to suggest a third reason that the Internet works: it gets the property boundaries right. Specifically, I see the Internet as a particularly striking example of what property theorist Henry Smith has named a semicommons.6 It mixes private property in individual computers and network links with a commons in the communications that flow * Associate Professor, New York Law School. My thanks for their comments to Jack Balkin, Shyam Balganesh, Aislinn Black, Anne Chen, Matt Haughey, Amy Kapczynski, David Krinsky, Jonathon Penney, Chris Riley, Henry Smith, Jessamyn West, and Steven Wu. I presented earlier versions of this essay at the Commons Theory Workshop for Young Scholars (Max Planck Institute for the Study of Collective Goods), the 2007 IP Scholars conference, the 2007 Telecommunications Policy Research Conference, and the December 2009 Symposium at Fordham Law School on David Post’s and Jonathan Zittrain’s books. -

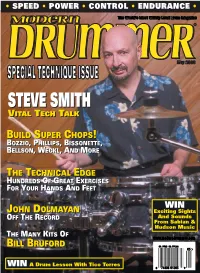

Steve Smith Steve Smith

• SPEED • POWER • CONTROL • ENDURANCE • SPECIAL TECHNIQUE ISSUE STEVESTEVE SMITHSMITH VVITALITAL TTECHECH TTALKALK BBUILDUILD SSUPERUPER CCHOPSHOPS!! BBOZZIOOZZIO,, PPHILLIPSHILLIPS,, BBISSONETTEISSONETTE,, BBELLSONELLSON,, WWECKLECKL,, AANDND MMOREORE TTHEHE TTECHNICALECHNICAL EEDGEDGE HHUNDREDSUNDREDS OOFF GGREATREAT EEXERCISESXERCISES FFOROR YYOUROUR HHANDSANDS AANDND FFEETEET WIN JJOHNOHN DDOLMAYANOLMAYAN Exciting Sights OOFFFF TTHEHE RRECORDECORD And Sounds From Sabian & Hudson Music TTHEHE MMANYANY KKITSITS OOFF BBILLILL BBRUFORDRUFORD $4.99US $6.99CAN 05 WIN A Drum Lesson With Tico Torres 0 74808 01203 9 Contents ContentsVolume 27, Number 5 Cover photo by Alex Solca STEVE SMITH You can’t expect to be a future drum star if you haven’t studied the past. As a self-proclaimed “US ethnic drummer,” Steve Smith has made it his life’s work to explore the uniquely American drumset— and the way it has shaped our music. by Bill Milkowski 38 Alex Solca BUILDING SUPER CHOPS 54 UPDATE 24 There’s more than one way to look at technique. Just ask Terry Bozzio, Thomas Lang, Kenny Aronoff, Bill Bruford, Dave Weckl, Paul Doucette Gregg Bissonette, Tommy Aldridge, Mike Mangini, Louie Bellson, of Matchbox Twenty Horacio Hernandez, Simon Phillips, David Garibaldi, Virgil Donati, and Carl Palmer. Gavin Harrison by Mike Haid of Porcupine Tree George Rebelo of Hot Water Music THE TECHNICAL EDGE 73 Duduka Da Fonseca An unprecedented gathering of serious chops-increasing exercises, samba sensation MD’s exclusive Technical Edge feature aims to do no less than make you a significantly better drummer. Work out your hands, feet, and around-the-drums chops like you’ve never worked ’em before. A DIFFERENT VIEW 126 TOM SCOTT You’d need a strongman just to lift his com- plete résumé—that’s how invaluable top musicians have found saxophonist Tom Scott’s playing over the past three decades.