The Jordan Valley

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Moving-Nowhere.Pdf

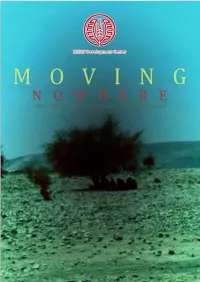

MA’AN Development Center MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 1 2 MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 2015 3 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Physical Security 6 Eviction Orders And Demolition Orders 10 Psychological Security 18 Livelihood Reductions 22 Environmental Concerns 24 Water 26 Settler Violence 28 Isuues Faced By Other Communities In Area C 32 International Humanitarian Law 36 Conclusion 40 Photo by Hamza Zbiedat Hamza by Photo 4 Moving Nowhere Introduction Indirect and direct forcible transfer is currently at the forefront of Israel’s ideological agenda in area C. Firing zones, initially established as a means of land control, are now being used to create an environment so hostile that Palestinians are forced to leave the area or live in conditions of deteriorating security. re-dating the creation of the state of Israel, there was an ideological agenda within Pcertain political spheres predicated on the notion that Israel should exist from the sea to the Jordan River. Upon creation of the State the subsequent governments sought to establish this notion. This has resulted in an uncompromising programme of colonisation, ethnic cleansing and de-development in Palestine. The conclusion of the six day war in 1967 marked the beginning of the ongoing occupation, under which the full force of the ideological agenda has been extended into the West Bank. Israel has continuously led projects and policies designed to appropriate vast amounts of Palestinian land in the West Bank, despite such actions being illegal under international law. -

Netanyahu's Annexation Plan Can't Be Stopped by Efraim Inbar

Netanyahu's Annexation Plan Can't Be Stopped by Efraim Inbar April 29, 2020 https://www.meforum.org/60838/netanyahu-annexation-plan-cant-be-stopped Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's plan to annex the Jordan Valley is not just a far-right wish, but the fulxllment of long- standing Israeli security objectives. Further, despite alarms by Netanyahu's critics in the United States and elsewhere about the plan, there is Annexation of the Jordan Valley is a long-standing objective actually widespread attracting widespread agreement among Israelis. agreement among Israelis about the strategic importance of the valley. That's why Blue and White leader Benny Gantz could sign off on the deal to form an emergency government. The consensus extends to Labor and even members of the opposition to the new national unity government. The extension of Israeli law to the Jordan Valley is in accordance with former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin's strategic tenets (the Allon Plan). Notably, more Israelis view the Jordan Valley as an indispensable defensible border than the Golan Heights. Defensible borders are More Israelis view the Jordan particularly necessary considering that the threats to Valley as indispensable than the Israel's population centers and Golan Heights. its strategic installations have increased in the 21st century. Iran hopes to establish a "Shiite Crescent" from the Gulf, via Iraq, Lebanon and Syria to the Mediterranean. Iran's objective is to turn Syria, Lebanon and Iraq into launching pads for missile and terror attacks against Israel. Iran also plans to destabilize the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and create a land bridge to the Palestinian Authority (close to Israel's heartland) in order to enhance its ability to harm Israel. -

B'tselem Report: Dispossession & Exploitation: Israel's Policy in the Jordan Valley & Northern Dead Sea, May

Dispossession & Exploitation Israel's policy in the Jordan Valley & northern Dead Sea May 2011 Researched and written by Eyal Hareuveni Edited by Yael Stein Data coordination by Atef Abu a-Rub, Wassim Ghantous, Tamar Gonen, Iyad Hadad, Kareem Jubran, Noam Raz Geographic data processing by Shai Efrati B'Tselem thanks Salwa Alinat, Kav LaOved’s former coordinator of Palestinian fieldworkers in the settlements, Daphna Banai, of Machsom Watch, Hagit Ofran, Peace Now’s Settlements Watch coordinator, Dror Etkes, and Alon Cohen-Lifshitz and Nir Shalev, of Bimkom. 2 Table of contents Introduction......................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Statistics........................................................................................................ 8 Land area and borders of the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea area....................... 8 Palestinian population in the Jordan Valley .................................................................... 9 Settlements and the settler population........................................................................... 10 Land area of the settlements .......................................................................................... 13 Chapter Two: Taking control of land................................................................................ 15 Theft of private Palestinian land and transfer to settlements......................................... 15 Seizure of land for “military needs”............................................................................. -

Mapping Peace Between Syria and Israel

UNiteD StateS iNStitUte of peaCe www.usip.org SpeCial REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Frederic C. Hof Commissioned in mid-2008 by the United States Institute of Peace’s Center for Mediation and Conflict Resolution, this report builds upon two previous groundbreaking works by the author that deal with the obstacles to Syrian- Israeli peace and propose potential ways around them: a 1999 Middle East Insight monograph that defined the Mapping peace between phrase “line of June 4, 1967” in its Israeli-Syrian context, and a 2002 Israel-Syria “Treaty of Peace” drafted for the International Crisis Group. Both works are published Syria and israel online at www.usip.org as companion pieces to this report and expand upon a concept first broached by the author in his 1999 monograph: a Jordan Valley–Golan Heights Environmental Preserve under Syrian sovereignty that Summary would protect key water resources and facilitate Syrian- • Syrian-Israeli “proximity” peace talks orchestrated by Turkey in 2008 revived a Israeli people-to-people contacts. long-dormant track of the Arab-Israeli peace process. Although the talks were sus- Frederic C. Hof is the CEO of AALC, Ltd., an Arlington, pended because of Israeli military operations in the Gaza Strip, Israeli-Syrian peace Virginia, international business consulting firm. He directed might well facilitate a Palestinian state at peace with Israel. the field operations of the Sharm El-Sheikh (Mitchell) Fact- Finding Committee in 2001. • Syria’s “bottom line” for peace with Israel is the return of all the land seized from it by Israel in June 1967. -

JORDAN, PALESTINE and ISRAEL Giulia Giordano and Lukas Rüttinger

MIDDLE EAST CLIMATE-FRAGILITY RISK BRIEF JORDAN, PALESTINE AND ISRAEL Giulia Giordano and Lukas Rüttinger This is a knowledge product provided by: CLIMATE-FRAGILITY RISK BRIEF: JORDAN, PALESTINE AND ISRAEL AUTHORED BY Dr. Giulia Giordano is an Italian researcher and practitioner with extensive experience in the Middle East. She is now the Director of International Programs at EcoPeace Middle East, a trilateral organization based in Israel, Jordan and Palestine. Her research interests are Middle Eastern studies, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and environmental diplomacy. Lukas Rüttinger is a Senior Advisor at adelphi, working at the intersection of environment, development, foreign and security policy. He has published widely on these topics and was the lead author of the 2015 report “A New Climate for Peace”. PROVIDED BY The Climate Security Expert Network, which comprises some 30 international experts, supports the Group of Friends on Climate and Security and the Climate Security Mechanism of the UN system. It does so by synthesising scientific knowledge and expertise, by advising on entry points for building resilience to climate-security risks, and by helping to strengthen a shared understanding of the challenges and opportunities of addressing climate-related security risks. www.climate-security-expert-network.org The climate diplomacy initiative is a collaborative effort of the German Federal Foreign Office in partnership with adelphi. The initiative and this publication are supported by a grant from the German Federal Foreign Office. www.climate-diplomacy.org SUPPORTED BY LEGAL NOTICE Contact: [email protected] Published by: adelphi research gGmbH, Alt-Moabit 91, 10559 Berlin, Germany www.adelphi.de CORPORATE DESIGN MANUAL The analysis, results, recommendations and graphics in this paper represent the opinion of STAND VOM 08.12.2010 the authors and are not necessarily representative of the position of any of the organisations listed above. -

Humanitarian Fact Sheet on the Jordan Valley and Dead Sea Area February 2012

UNITED NATIONS Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory HUMANITARIAN FACT SHEET ON THE JORDAN VALLEY AND DEAD SEA AREA FEBRUARY 2012 KEY FACTS � The Jordan Valley and Dead Sea area covers around 30% of the West Bank, and is home to nearly 60,000 Palestinians. � 87% of the land is designated as Area C, virtually all of which is prohibited for Palestinian use, earmarked instead for the use of the Israeli military or under the jurisdiction of Israeli settlements. � An additional 7% is formally part of Area B, but is unavailable for development, as it was designated a nature reserve under the 1998 Wye River Memorandum. � Around one quarter of Palestinians in the area reside in Area C, including some 7,900 Bedouin and herders. Some 3,400 people reside partially or fully in closed military zones and face a high risk of forced eviction. � There are 37 Israeli settlements, with a population of 9,500, established across the area, in contravention of international law. � In 2011, the Israeli authorities demolished over 200 Palestinian-owned structures in the area, displacing around 430 people and affecting the livelihoods of another 1,200 Palestinians. � Water consumption dips to 20 litres/capita/day in most herding communities in the area, compared to the WHO recommendation of 100 l/c/d and the average settlement consumption of 300 l/c/d. � Access to the area is limited to six routes, four of which are controlled by Israeli checkpoints, severely restricting the movement of Palestinian-plated vehicles. � If Palestinians gain access to 50,000 dunums (12,500 acres or 3.5% of Area C) of uncultivated land, this could generate a billion dollars of revenue per year (The World Bank). -

The Impact of Scarce Water Resources on the Arab-Israeli Conflict

Volume 32 Issue 4 Fall 1992 Winter 1992 The Impact of Scarce Water Resources on the Arab-Israeli Conflict Aaron Wolf John Ross Recommended Citation Aaron Wolf & John Ross, The Impact of Scarce Water Resources on the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 32 Nat. Resources J. 919 (1992). Available at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/nrj/vol32/iss4/8 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Natural Resources Journal by an authorized editor of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. AARON WOLF and JOHN ROSS* The Impact of Scarce Water Resources on the Arab-Israeli Conflict ABSTRACT The Jordan River watershed is included within the borders of countries and territorieseach of whose water consumption is cur- rently approachingor surpassingannual recharge. The region is als6 particularly volatile politically, with five Arab-Israeli wars since 1948, and many tenacious issues yet unresolved. This paper suggests that scarce water resources are actually inextricably related to regional conflict, having led historically to intense, and sometimes armed, competition, but also to occasional instances of cooperation between otherwise hostile players. The focus on water as a strategic resource has particularrelevance to policy options given,for example, Israel's reliance on the West Bank for a share of its water resources, and the water needs of at least one impending wave of immigration to the region. Included in the paper are sections describing the natural hydrography and water consumption patterns of the region, a brief history of political events affected by 'hydro-strategic'considerations, and a survey of some resource strategy alternativesfor the future. -

Chapter 2: the Middle East Conflict in Outline

2 7KH0LGGOH(DVW&RQIOLFWLQ2XWOLQH Origins of the Conflict 2.1 The modern Middle East conflict between Israel and neighbouring Arab states could be said to have begun in 1897 when Theodor Hertzl convened the First World Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland. With Jews facing increased discrimination and pogroms in Europe and Russia, Dr Hertzl called for the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. 2.2 During the First World War, British officials in the Middle East promised independence to the Arabs in return for their support against Turkey. The 1916 Anglo-French (Sykes-Pikot) Agreement broke this promise and the region was divided into spheres of influence between France and Britain. Meanwhile, the campaign for a Jewish homeland continued, culminating in the Balfour Declaration of 2 November 1917, which stated that Britain viewed with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people. The Declaration, in the form of a letter from the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Balfour, was addressed to Baron Rothschild, a leader of British Jewry, following consideration in the Cabinet.1 The Declaration also indicated that, in supporting such an aim: … nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or 1 Historical material is this Chapter has been drawn from a number of sources, particularly— The BBC World Service website: www.bbc.co.uk/worldservice/middleeast; the Avalon Project, Yale Law School website: www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/mideast/; M Ong, Department of the Parliamentary Library, Current Issues Brief No. 6, 2000-01, The Middle East Crisis: Losing Control?, 5 December 2000; L Joffe, Keesing's Guide to the Mid-East Peace Process, Catermill Publishing, London, 1996; and The Palestinian-Israeli Peace Agreement: A Documentary Record, published by the Institute for Palestine Studies, Washington DC, 1993. -

4 Reasons Why Israel's West Bank Annexation Plans Didn't Happen Yet

Editorials ..................................... 4A Op-Ed .......................................... 5A Calendar ...................................... 6A Scene Around ............................. 9A Synagogue Directory ................ 11A News Briefs ............................... 13A WWW.HERITAGEFL.COM YEAR 44, NO. 45 JULY 10, 2020 18 TAMUZ, 5780 ORLANDO, FLORIDA SINGLE COPY 75¢ Legislators show support at CUFI WASHINGTON, D.C. — Summit. Regardless of party, Today, members of the U.S. its elected officials, like the House of Representatives ones from whom we heard, and Senate conveyed their who strengthen the US-Israel unequivocal support for the relationship and stand up to U.S.-Israel relationship at day anti-Semitism. I am deeply three of Christians United for grateful to all of the Members IsraeI’s 15th Annual Sum- of Congress who addressed mit. CUFI’s Summit, being our Summit,” said CUFI conducted virtually this year, founder and chairman, Pastor featured numerous legislators John Hagee. from both chambers of Con- CUFI, the nation’s largest gress reassuring their strong pro-Israel organization, was commitments to stand with honored to hear from con- Israel to CUFI members across gressional leaders Senator the country. Speaking to Marco Rubio, Senator Tim thousands of dedicated CUFI Scott, Senator Tom Cotton, Yaniv Nadav/Flash90 members, some of Israel’s Senator Ted Cruz, Senator A view of the Jordan Valley, part of the land that Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu wants to apply Israeli strongest congressional allies Marsha Blackburn, Senator sovereignty to, seen Feb. 2, 2020. delivered impactful messages James Lankford, Senator discussing topics ranging Jacky Rosen and Representa- from standing with Israel, to tive Dan Crenshaw on the 4 reasons why Israel’s West Bank confronting Iran, and com- strategic alliance between the bating anti-Semitism. -

Best Line of Defense: the Case for Israeli Sovereignty in the Jordan Valley

Best Line of Defense: The Case for Israeli Sovereignty in the Jordan Valley JINSA’s Gemunder Center for Defense and Strategy June 2020 DISCLAIMER This report is a product of JINSA’s Gemunder Center for Defense & Strategy. The report does not necessarily represent the views or opinions of JINSA, its founders or its board of directors. Cover image credit: Getty Images Policy Project Staff, Contributors and Advisors JINSA Staff & Contributors Michael Makovsky, PhD President & CEO Gen Charles “Chuck” Wald, USAF (ret.) Distinguished Fellow/Senior Advisor, Gemunder Center for Defense & Strategy; Former Deputy Commander of U.S. European Command Sander Gerber Distinguished Fellow, Gemunder Center for Defense & Strategy Steven Rosen Senior Fellow, Gemunder Center for Defense & Strategy Charles B. Perkins Director for U.S.-Israel Security Policy Abraham Katsman Fellow, Gemunder Center for Defense & Strategy Advisors IDF MG (ret.) Yaakov Amidror Distinguished Fellow, Gemunder Center for Defense & Strategy IDF MG (ret.) Yaacov Ayish Senior Vice President for Israeli Affairs Table of Contents I. Executive Summary 7 II. Geostrategic Importance of the Jordan Valley 10 III. Israeli Control Requires Israeli Sovereignty 16 IV. Legal Basis for Extending Israeli Sovereignty 20 V. Potential Risks, But Manageable 21 Endnotes 26 I. Executive Summary Israel’s recently declared intent to extend sovereignty to parts of the West Bank beginning in July, based on the Trump peace plan, has sparked passionate discussion. Often overlooked is the distinction between Israel extending its sovereignty to all proposed areas of the West Bank, versus just to the Jordan Valley. The former encompasses 29 percent of heavily populated areas in the West Bank, while the sparsely populated Jordan Valley comprises just 15 percent of the West Bank’s landmass.* And the Jordan Valley is a critical slice of strategic territory that holds the key to Israel’s security. -

Pastoral Communities of the Jordan Valley

Pastoral FACT SHEET Communities of the Jordan Valley SNAPSHOT BACKGROUND The Jordan Valley covers almost a third of the West Bank, The Jordan Valley, with its fertile lands and plentiful water extending from the Green Line in the north to the Dead Sea in the sources, has for centuries been home to semi-nomadic pastoral south, and from the Jordan River in the east to the hills in the west. communities. After the 1948 War, when Israel established a state and hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were expelled from Today, nearly 60,000 Palestinians live in the Jordan Valley. While their homes, many refugees fled to the Jordan Valley.7 most are concentrated in the district of Jericho, many semi- nomadic communities are scattered across the rest of the Valley. However, when Israel occupied the West Bank in 1967, hundreds These communities, generally speaking, live and try to maintain of families fled the Jordan Valley. The Israeli military confiscated their pastoral way of life.1 About 87 percent of the land they thousands of dunums of land, deeming the Palestinian owners have traditionally used for grazing and small-scale agriculture, who had been pushed out “absentees.”8 Since then, Israel has however, now falls under full Israeli control (Area C).2 An taken a number of measures to make it difficult if not impossible additional 7% of the land is part of Area B but is unavailable for for these refugees to return to their lands in the Jordan Valley. development as it was designated a nature reserve under the 1998 Israel immediately began the -

Assessment of the Agricultural Water Use in Jericho Governorate Using Sefficiency

sustainability Article Assessment of the Agricultural Water Use in Jericho Governorate Using Sefficiency Nasser Tuqan 1,* , Naim Haie 1 and Muhammad Tajuri Ahmad 2 1 CTAC, University of Minho, Azurem Campus, 4800-058 Guimarães, Portugal; [email protected] 2 Civil Engineering Department, Kano University of Science & Technology, Wudil 713281, Nigeria; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +351-939-537-252 Received: 25 March 2020; Accepted: 29 April 2020; Published: 1 May 2020 Abstract: Addressing water use efficiency in the Middle East is challenging due to the geopolitical complexity, climatic conditions and a variety of managerial issues. Groundwater is the dominant water resource for Palestinians, while aquifers are shared with their neighbours. We assessed in this study the efficiency of the agricultural water use in Jericho, which we defined as the Water Use System (WUS), and its impact on the main source, the Eastern Aquifer Basin (EAB), using the Sustainable Efficiency (Sefficiency) method. The assessment considered the objectives’ difference between the farmers in the region and the water managers. As Sefficiency requires, the analysis also considered in addition to the quantities of the different water path types within our WUS, their quality and beneficial weights. The results highlighted efficiency improvement potentials, a substantial number of unreported abstractions and an impact of the use of chemical substances on the main source. In addition, through hypothesizing four scenarios, we demonstrated that: 1. Improving the quality of returns has a great positive impact. 2. Increasing water abstractions is not beneficial if it is not linked to an increase in yield production.