Assessment of the Agricultural Water Use in Jericho Governorate Using Sefficiency

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why the Walls of Jericho Came Tumbling Down

WHY THE WALLS OF JERICHO CAME TUMBLING DOWN SHUBERT SPERO What follows is an attempt to give a rational explanation for the fall of the walls of Jericho following the siege of the city by the Israelite forces led by 1 Joshua. The theory I wish to propose is designed not to replace the textual account but to complement it. That is, to suggest a reality that does not contradict the official version but which may have been behind it and for whose actual occurrence several hints may be found in the text. The fall of the walls of Jericho was indeed a wondrous event and the text properly sees God as the agent in the sense that it was He who inspired Joshua to come up 2 with his ingenious plan. Our theory suggests a connection between the two outstanding features of the story: (1) The adventure of the two Israelite spies in the house of Rahab the inn-keeper, before the Israelites crossed the Jordan, and (2) the mystify- ing circling of the city by the priestly procession for the seven days preceding the tumbling down of the walls. Let us first review the salient facts involved in the incident of the spies. We are told that Rahab's dwelling was part of the city wall and that in the wall she dwelt (Josh. 2:15) with a window that looked out on the area outside the city. The spies avoid capture by the Canaanite authorities through the efforts of Rahab and, in gratitude, they promise the woman that she and her family will not be harmed during the impending attack, and instruct her to gather them all into her house and hang scarlet threads in the window. -

Gog and Magog Battle Israel

ISRAEL IN PROPHECY LESSON 5 GOG AND MAGOG BATTLE ISRAEL The “latter days” battle against Israel described in Ezekiel is applied by dispensationalists to a coming battle against the modern nation of Israel in Palestine. The majority of popular Bible commentators try to map out this battle and even name nations that will take part in it. In this lesson you will see that this prophecy in Ezekiel chapters 36 and 37 does not apply to the modern nation of Israel at all. You will study how the book of Revelation gives us insights into how this prophecy will be applied to God’s people, spiritual Israel (the church) in the last days. You will also see a clear parallel between the events described in Ezekiel’s prophecy and John’s description of the seven last plagues in Revelation. This prophecy of Ezekiel gives you another opportunity to learn how the “Three Fold Application” applies to Old Testament prophecy. This lesson lays out how Ezekiel’s prophecy was originally given to the literal nation of Israel at the time of the Babylonian captivity, and would have met a victorious fulfillment if they had remained faithful to God and accepted their Messiah, Jesus Christ. However, because of Israel’s failure this prophecy is being fulfilled today to “spiritual Israel”, the church in a worldwide setting. The battle in Ezekiel describes Satan’s last efforts to destroy God’s remnant people. It will intensify as we near the second coming of Christ. Ezekiel’s battle will culminate and reach it’s “literal worldwide in glory” fulfillment at the end of the 1000 years as described in Revelation chapter 20. -

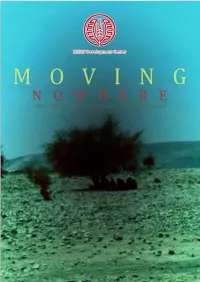

Moving-Nowhere.Pdf

MA’AN Development Center MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 1 2 MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 2015 3 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Physical Security 6 Eviction Orders And Demolition Orders 10 Psychological Security 18 Livelihood Reductions 22 Environmental Concerns 24 Water 26 Settler Violence 28 Isuues Faced By Other Communities In Area C 32 International Humanitarian Law 36 Conclusion 40 Photo by Hamza Zbiedat Hamza by Photo 4 Moving Nowhere Introduction Indirect and direct forcible transfer is currently at the forefront of Israel’s ideological agenda in area C. Firing zones, initially established as a means of land control, are now being used to create an environment so hostile that Palestinians are forced to leave the area or live in conditions of deteriorating security. re-dating the creation of the state of Israel, there was an ideological agenda within Pcertain political spheres predicated on the notion that Israel should exist from the sea to the Jordan River. Upon creation of the State the subsequent governments sought to establish this notion. This has resulted in an uncompromising programme of colonisation, ethnic cleansing and de-development in Palestine. The conclusion of the six day war in 1967 marked the beginning of the ongoing occupation, under which the full force of the ideological agenda has been extended into the West Bank. Israel has continuously led projects and policies designed to appropriate vast amounts of Palestinian land in the West Bank, despite such actions being illegal under international law. -

The Bible, the Qur'an and Science

مكتبةمكتبة مشكاةمشكاة السإلميةالسإلمية The Bible, The Qur'an and Science The Holy Scriptures Examined In The Light Of Modern Knowledge by Dr. Maurice Bucaille Translated from French by Alastair D. Pannell and The Author مكتبةمكتبة مشكاةمشكاة السإلميةالسإلمية Table of Contents Foreword.........................................................................................3 Introduction......................................................................................3 The Old Testament..........................................................................9 The Books of the Old Testament...................................................13 The Old Testament and Science Findings....................................23 Position Of Christian Authors With Regard To Scientific Error In The Biblical Texts...........................................................................33 Conclusions...................................................................................37 The Gospels..................................................................................38 Historical Reminder Judeo-Christian and Saint Paul....................41 The Four Gospels. Sources and History.......................................44 The Gospels and Modern Science. The General Genealogies of Jesus.........................................................................................62 Contradictions and Improbabilities in the Descriptions.................72 Conclusions...................................................................................80 -

Occupied Palestinian Territory (Including East Jerusalem)

Reporting period: 29 March - 4 April 2016 Weekly Highlights For the first week in almost six months there have been no Palestinian nor Israeli fatalities recorded. 88 Palestinians, including 18 children, were injured by Israeli forces across the oPt. The majority of injuries (76 per cent) were recorded during demonstrations marking ‘Land Day’ on 30 March, including six injured next to the perimeter fence in the Gaza Strip, followed by search and arrest operations. The latter included raids in Azzun ‘Atma (Qalqiliya) and Ya’bad (Jenin) involving property damage and the confiscation of two vehicles, and a forced entry into a school in Ras Al Amud in East Jerusalem. On 30 occasions, Israeli forces opened fire in the Access Restricted Area (ARA) at land and sea in Gaza, injuring two Palestinians as far as 350 meters from the fence. Additionally, Israeli naval forces shelled a fishing boat west of Rafah city, destroying it completely. Israeli forces continued to ban the passage of Palestinian males between 15 and 25 years old through two checkpoints controlling access to the H2 area of Hebron city. This comes in addition to other severe restrictions on Palestinian access to this area in place since October 2015. During the reporting period, Israeli forces removed the restrictions imposed last week on Beit Fajjar village (Bethlehem), which prevented most residents from exiting and entering the village. This came following a Palestinian attack on Israeli soldiers near Salfit, during which the suspected perpetrators were killed. Israeli forces also opened the western entrance to Hebron city, which connects to road 35 and to the commercial checkpoint of Tarqumiya. -

Nablus Salfit Tubas Tulkarem

Iktaba Al 'Attara Siris Jaba' (Jenin) Tulkarem Kafr Rumman Silat adh DhahrAl Fandaqumiya Tubas Kashda 'Izbat Abu Khameis 'Anabta Bizzariya Khirbet Yarza 'Izbat al Khilal Burqa (Nablus) Kafr al Labad Yasid Kafa El Far'a Camp Al Hafasa Beit Imrin Ramin Ras al Far'a 'Izbat Shufa Al Mas'udiya Nisf Jubeil Wadi al Far'a Tammun Sabastiya Shufa Ijnisinya Talluza Khirbet 'Atuf An Naqura Saffarin Beit Lid Al Badhan Deir Sharaf Al 'Aqrabaniya Ar Ras 'Asira ash Shamaliya Kafr Sur Qusin Zawata Khirbet Tall al Ghar An Nassariya Beit Iba Shida wa Hamlan Kur 'Ein Beit el Ma Camp Beit Hasan Beit Wazan Ein Shibli Kafr ZibadKafr 'Abbush Al Juneid 'Azmut Kafr Qaddum Nablus 'Askar Camp Deir al Hatab Jit Sarra Salim Furush Beit Dajan Baqat al HatabHajja Tell 'Iraq Burin Balata Camp 'Izbat Abu Hamada Kafr Qallil Beit Dajan Al Funduq ImmatinFar'ata Rujeib Madama Burin Kafr Laqif Jinsafut Beit Furik 'Azzun 'Asira al Qibliya 'Awarta Yanun Wadi Qana 'Urif Khirbet Tana Kafr Thulth Huwwara Odala 'Einabus Ar Rajman Beita Zeita Jamma'in Ad Dawa Jafa an Nan Deir Istiya Jamma'in Sanniriya Qarawat Bani Hassan Aqraba Za'tara (Nablus) Osarin Kifl Haris Qira Biddya Haris Marda Tall al Khashaba Mas-ha Yasuf Yatma Sarta Dar Abu Basal Iskaka Qabalan Jurish 'Izbat Abu Adam Talfit Qusra Salfit As Sawiya Majdal Bani Fadil Rafat (Salfit) Khirbet Susa Al Lubban ash Sharqiya Bruqin Farkha Qaryut Jalud Kafr ad Dik Khirbet Qeis 'Ammuriya Khirbet Sarra Qarawat Bani Zeid (Bani Zeid al Gharb Duma Kafr 'Ein (Bani Zeid al Gharbi)Mazari' an Nubani (Bani Zeid qsh Shar Khirbet al Marajim 'Arura (Bani Zeid qsh Sharqiya) Bani Zeid 'Abwein (Bani Zeid ash Sharqiya) Sinjil Turmus'ayya. -

Palestine - Walking Through History

Palestine - Walking through History April 04 - 08, 2019 Cultural Touring | Hiking | Cycling | Jeep touring Masar Ibrahim Al-Khalil is Palestine’s long distance cultural walking route. Extending 330 km from the village of Rummana in the northwest of Jenin to Beit Mirsim southwest of Al-Haram al-Ibrahimi (Ibrahimi Mosque) in Hebron. The route passes through more than fifty cities and villages where travelers can experience the legendary Palestinian hospitality. Beginning with a tour of the major sites in Jerusalem, we are immediately immersed in the complex history of the region. Over the five days, we experience sections of this route, hiking and biking from the green hills of the northern West Bank passing through the desert south of Jericho to Bethlehem. Actively traveling through the varied landscapes, biodiverse areas, archaeological remains, religious sites, and modern day lively villages, we experience rich Palestinian culture and heritage. Palestinians, like their neighboring Arabs, are known for their welcoming warmth and friendliness, important values associated with Abraham (Ibrahim). There is plenty of opportunity to have valuable encounters with local communities who share the generosity of their ancestors along the way, often over a meal of delicious Palestinian cuisine. The food boasts a range of vibrant and flavorsome dishes, sharing culinary traits with Middle Eastern and East Mediterranean regions. Highlights: ● Experience Palestine from a different perspective – insights that go beyond the usual headlines ● Hike and bike through beautiful landscapes ● Witness history in Jerusalem, Sebastiya, Jericho, Bethlehem ● Map of the route ITINERARY Day 1 – 04 April 2019 - Thursday : Our trip begins today with a 8:00am pick-up at the hotel in Aqaba, the location on AdventureNEXT Near East. -

Muslim Women's Pilgrimage to Mecca and Beyond

Muslim Women’s Pilgrimage to Mecca and Beyond This book investigates female Muslims pilgrimage practices and how these relate to women’s mobility, social relations, identities, and the power struc- tures that shape women’s lives. Bringing together scholars from different disciplines and regional expertise, it offers in-depth investigation of the gendered dimensions of Muslim pilgrimage and the life-worlds of female pilgrims. With a variety of case studies, the contributors explore the expe- riences of female pilgrims to Mecca and other pilgrimage sites, and how these are embedded in historical and current contexts of globalisation and transnational mobility. This volume will be relevant to a broad audience of researchers across pilgrimage, gender, religious, and Islamic studies. Marjo Buitelaar is an anthropologist and Professor of Contemporary Islam at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands. She is programme-leader of the research project ‘Modern Articulations of Pilgrimage to Mecca’, funded by the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Manja Stephan-Emmrich is Professor of Transregional Central Asian Stud- ies, with a special focus on Islam and migration, at the Institute for Asian and African Studies at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, Germany, and a socio-cultural anthropologist. She is a Principal Investigator at the Berlin Graduate School Muslim Cultures and Societies (BGSMCS) and co-leader of the research project ‘Women’s Pathways to Professionalization in Mus- lim Asia. Reconfiguring religious knowledge, gender, and connectivity’, which is part of the Shaping Asia network initiative (2020–2023, funded by the German Research Foundation, DFG). Viola Thimm is Professorial Candidate (Habilitandin) at the Institute of Anthropology, University of Heidelberg, Germany. -

Al 'Auja Town Profile

Al 'Auja Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Jericho Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, town committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Jericho Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, village, and town in the Jericho Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Jericho Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in the Jericho Governorate. In addition, the project aims at preparing strategic developmental programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current political, social, and economic instability with special emphasize on agriculture, environment and water. -

Saul, Benjamin, and the Emergence of Monarchy in Israel

SAUL, BENJAMIN, AND THE EMERGENCE OF MONARCHY IN ISRAEL Press SBL ANCIENT ISRAEL AND ITS LITERATURE Thomas C. Römer, General Editor Editorial Board: Susan Ackerman Thomas B. Dozeman Alphonso Groenewald Shuichi Hasegawa Konrad Schmid Naomi A. Steinberg Number 40 Press SBL SAUL, BENJAMIN, AND THE EMERGENCE OF MONARCHY IN ISRAEL Biblical and Archaeological Perspectives Edited by Joachim J. Krause, Omer Sergi, and Kristin Weingart Press SBL Atlanta Copyright © 2020 by SBL Press All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permit- ted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Office, SBL Press, 825 Hous- ton Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Krause, Joachim J., editor. | Sergi, Omer, 1977– editor. | Weingart, Kristin, 1974– editor. Other titles: Ancient Israel and its literature ; no. 40. Title: Saul, Benjamin and the emergence of monarchy in Israel : biblical and archaeological perspectives / edited by Joachim J. Krause, Omer Sergi, and Kristin Weingart. Description: Atlanta : SBL Press, 2020. | Series: Ancient Israel and its literature ; 40 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020012825 (print) | LCCN 2020012826 (ebook) | ISBN 9781628372816 (paperback) | ISBN 9780884144502 (hardback) | ISBN 9780884144519 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Saul, King of Israel. | Benjamin (Biblical figure) | Bible. Samuel. | Bible. Kings. | Jews—Kings and rulers. | Monarchy—Palestine—History. | Excavations (Archaeology)—Palestine. -

Netanyahu's Annexation Plan Can't Be Stopped by Efraim Inbar

Netanyahu's Annexation Plan Can't Be Stopped by Efraim Inbar April 29, 2020 https://www.meforum.org/60838/netanyahu-annexation-plan-cant-be-stopped Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's plan to annex the Jordan Valley is not just a far-right wish, but the fulxllment of long- standing Israeli security objectives. Further, despite alarms by Netanyahu's critics in the United States and elsewhere about the plan, there is Annexation of the Jordan Valley is a long-standing objective actually widespread attracting widespread agreement among Israelis. agreement among Israelis about the strategic importance of the valley. That's why Blue and White leader Benny Gantz could sign off on the deal to form an emergency government. The consensus extends to Labor and even members of the opposition to the new national unity government. The extension of Israeli law to the Jordan Valley is in accordance with former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin's strategic tenets (the Allon Plan). Notably, more Israelis view the Jordan Valley as an indispensable defensible border than the Golan Heights. Defensible borders are More Israelis view the Jordan particularly necessary considering that the threats to Valley as indispensable than the Israel's population centers and Golan Heights. its strategic installations have increased in the 21st century. Iran hopes to establish a "Shiite Crescent" from the Gulf, via Iraq, Lebanon and Syria to the Mediterranean. Iran's objective is to turn Syria, Lebanon and Iraq into launching pads for missile and terror attacks against Israel. Iran also plans to destabilize the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and create a land bridge to the Palestinian Authority (close to Israel's heartland) in order to enhance its ability to harm Israel. -

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec

Israel's Conquest of Canaan: Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 Author(s): Lewis Bayles Paton Reviewed work(s): Source: Journal of Biblical Literature, Vol. 32, No. 1 (Apr., 1913), pp. 1-53 Published by: The Society of Biblical Literature Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3259319 . Accessed: 09/04/2012 16:53 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The Society of Biblical Literature is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Journal of Biblical Literature. http://www.jstor.org JOURNAL OF BIBLICAL LITERATURE Volume XXXII Part I 1913 Israel's Conquest of Canaan Presidential Address at the Annual Meeting, Dec. 27, 1912 LEWIS BAYLES PATON HARTFORD THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY problem of Old Testament history is more fundamental NO than that of the manner in which the conquest of Canaan was effected by the Hebrew tribes. If they came unitedly, there is a possibility that they were united in the desert and in Egypt. If their invasions were separated by wide intervals of time, there is no probability that they were united in their earlier history. Our estimate of the Patriarchal and the Mosaic traditions is thus conditioned upon the answer that we give to this question.