Chapter 2: the Middle East Conflict in Outline

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israeli Settlement Goods

British connections with Israeli Companies involved in the Trade union briefing settlements settlements Key Israeli companies which export settlement products to the Over 50% of Israel’s agricultural produce is imported by UK are: the European Union, of which a large percentage arrives in British stores, including all the main supermarkets. These Agricultural Export Companies: Carmel-Agrexco, Hadiklaim, include: Asda, Tesco, Waitrose, John Lewis, Morrisons, and Mehadrin-Tnuport, Arava, Jordan River, Jordan Plains, Flowers Sainsburys. Direct Other food products: Abady Bakery, Achdut, Adumim Food ISRAELI SETTLEMENT The Soil Association aids the occupation by providing Additives/Frutarom, Amnon & Tamar, Oppenheimer, Shamir certification to settlement products. Salads, Soda Club In December 2009, following significant consumer pressure, Dead Sea Products: Ahava, Dead Sea Laboratories, Intercosma the Department for Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) issued GOODS: BAN THEM, guidelines for supermarkets on settlement labeling — Please note that some of these companies also produce differentiating goods grown in settlements from goods legitimate goods in Israel. It is goods from the illegal grown on Palestinian farms. Although this guidance is not settlements that we want people to boycott. compulsory, many supermarkets are already saying that they don’t buy THEM! will adopt this labeling, so consumers will know if goods Companies working in the are grown in illegal Israeli settlements. DEFRA also stated that companies will be committing an offence -

Hizballah's Vision of the Lebanon-Israel Border by Avi Jorisch

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 368 Hizballah's Vision of the Lebanon-Israel Border by Avi Jorisch Mar 4, 2002 ABOUT THE AUTHORS Avi Jorisch Avi Jorisch is an adjunct scholar of The Washington Institute and author of its new monograph and CD-ROM Beacon of Hatred: Inside Hizballah's al-Manar Television (2004). As the Institute's Soref fellow from 2001 to 2003, he specialized in Arab and Islamic politics. More recently, he served as an Brief Analysis n February 28, Hizballah fired 57mm antiaircraft missiles at Israeli planes flying over the Shebaa Farms O area. According to Hizballah information officer Hassan Azzedin, "the current line of Israeli withdrawal ('blue line') is not consistent with the international boundary and not recognized by the Lebanese government. That's why we're pursuing the path of resistance." Indeed, Hizballah claims that Israel continues to occupy sovereign Lebanese territory, and the organization makes this claim the basis for what it considers legitimate resistance. What, then, is Hizballah's vision of where the Lebanon-Israel border should lie? Background Between 1920 and 1924, French and British negotiators delineated the border between Le Grand Liban and Mandatory Palestine. After the 1948 war, the Lebanese and Israelis established the Armistice Demarcation Line (ADL), which coincided with the 1924 international border. From 1982 to 2000, Israel occupied a section of southern Lebanon, and, upon his election in July 1999, then-Prime Minister Ehud Barak announced his intention to withdraw the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) from Lebanon, which he did on May 25, 2000. Before the Israeli withdrawal, Hizballah maintained that if Israel were to retain even "one inch of Lebanese land," resistance operations would continue. -

Forming a Nucleus for the Jewish State

Table of Contents Introduction ........................................................................................... 3 Jewish Settlements 70 CE - 1882 ......................................................... 4 Forming a Nucleus for First Aliyah (1882-1903) ...................................................................... 5 Second Aliyah (1904-1914) .................................................................. 7 the Jewish State: Third Aliyah (1919-1923) ..................................................................... 9 First and Second Aliyot (1882-1914) ................................................ 11 First, Second, and Third Aliyot (1882-1923) ................................... 12 1882-1947 Fourth Aliyah (1924-1929) ................................................................ 13 Fifth Aliyah Phase I (1929-1936) ...................................................... 15 First to Fourth Aliyot (1882-1929) .................................................... 17 Dr. Kenneth W. Stein First to Fifth Aliyot Phase I (1882-1936) .......................................... 18 The Peel Partition Plan (1937) ........................................................... 19 Tower and Stockade Settlements (1936-1939) ................................. 21 The Second World War (1940-1945) ................................................ 23 Postwar (1946-1947) ........................................................................... 25 11 Settlements of October 5-6 (1947) ............................................... 27 First -

Did the San Remo Conference Advance Or Undermine the Prospects for a Jewish State? » Mosaic

12/1/2020 Did the San Remo Conference Advance or Undermine the Prospects for a Jewish State? » Mosaic DID THE SAN REMO CONFERENCE ADVANCE OR UNDERMINE THE PROSPECTS FOR A JEWISH STATE? https://mosaicmagazine.com/observation/israel-zionism/2020/12/did-the-san-remo-conference-advance-or-undermine-the-prospects-for-a-jewish-state/ As a Jew, I wish that the resolution signed 100 years ago had been what today’s celebrants claim it was. As a historian of Israel, I must report that it was much less. December 1, 2020 | Martin Kramer About the author: Martin Kramer teaches Middle Eastern history and served as founding president at Shalem College in Jerusalem, and is the Walter P. Stern fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Three years ago this month, Israel marked not one but two major anniversaries: the centennial of the Balfour Declaration, announcing British support for a Jewish national home in Palestine (November 2, 1917), and 70 years since the UN General Assembly partition resolution calling for separate Jewish and Arab states in Palestine (November 29, 1947). Both are widely recognized as landmarks on the road to Israeli independence. This year, though, we’ve been told by Zionist organizations, Israeli officials, and political activists that we should really be celebrating a different date entirely: namely, this year’s centennial of an international conference held in San Remo on the Italian Riviera in late April 1920. At that conference, a sequel to the post-World War I Paris peace conference of 1919, Britain and France (along with Italy and Japan) agreed on the division of the post- Ottoman Levant and Mesopotamia into League of Nations mandates. -

The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917-1947 / by Fred Lennis Lepkin

THE BRITISH LABOUR PARTY AND ZIONISM: 1917 - 1947 FRED LENNIS LEPKIN BA., University of British Columbia, 196 1 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of History @ Fred Lepkin 1986 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY July 1986 All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. Name : Fred Lennis Lepkin Degree: M. A. Title of thesis: The British Labour Party and Zionism, - Examining Committee: J. I. Little, Chairman Allan B. CudhgK&n, ior Supervisor . 5- - John Spagnolo, ~upervis&y6mmittee Willig Cleveland, Supepiso$y Committee -Lenard J. Cohen, External Examiner, Associate Professor, Political Science Dept.,' Simon Fraser University Date Approved: August 11, 1986 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENSE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis, project or extended essay (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this work for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this work for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Project/Extended Essay The British Labour Party and Zionism, 1917 - 1947. -

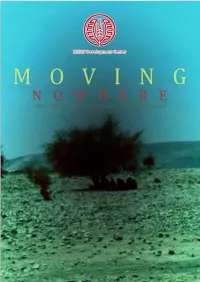

Moving-Nowhere.Pdf

MA’AN Development Center MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 1 2 MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 2015 3 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Physical Security 6 Eviction Orders And Demolition Orders 10 Psychological Security 18 Livelihood Reductions 22 Environmental Concerns 24 Water 26 Settler Violence 28 Isuues Faced By Other Communities In Area C 32 International Humanitarian Law 36 Conclusion 40 Photo by Hamza Zbiedat Hamza by Photo 4 Moving Nowhere Introduction Indirect and direct forcible transfer is currently at the forefront of Israel’s ideological agenda in area C. Firing zones, initially established as a means of land control, are now being used to create an environment so hostile that Palestinians are forced to leave the area or live in conditions of deteriorating security. re-dating the creation of the state of Israel, there was an ideological agenda within Pcertain political spheres predicated on the notion that Israel should exist from the sea to the Jordan River. Upon creation of the State the subsequent governments sought to establish this notion. This has resulted in an uncompromising programme of colonisation, ethnic cleansing and de-development in Palestine. The conclusion of the six day war in 1967 marked the beginning of the ongoing occupation, under which the full force of the ideological agenda has been extended into the West Bank. Israel has continuously led projects and policies designed to appropriate vast amounts of Palestinian land in the West Bank, despite such actions being illegal under international law. -

Britain's Broken Promises: the Roots of the Israeli and Palestinian

Britain’s Broken Promises: The Roots of the Israeli and Palestinian Conflict Overview Students will learn about British control over Palestine after World War I and how it influenced the Israel‐Palestine situation in the modern Middle East. The material will be introduced through a timeline activity and followed by a PowerPoint that covers many of the post‐WWI British policies. The lesson culminates in a letter‐writing project where students have to support a position based upon information learned. Grade 9 NC Essential Standards for World History • WH.1.1: Interpret data presented in time lines and create time lines • WH.1.3: Consider multiple perspectives of various peoples in the past • WH.5.3: Analyze colonization in terms of the desire for access to resources and markets as well as the consequences on indigenous cultures, population, and environment • WH.7.3: Analyze economic and political rivalries, ethnic and regional conflicts, and nationalism and imperialism as underlying causes of war Materials • “Steps Toward Peace in Israel and Palestine” Timeline (excerpt attached) • History of Israel/Palestine Timeline Questions and Answer Key, attached • Drawing paper or chart paper • Colored pencils or crayons (optional) • “Britain’s Broken Promises” PowerPoint, available in the Database of K‐12 Resources (in PDF format) o To view this PDF as a projectable presentation, save the file, click “View” in the top menu bar of the file, and select “Full Screen Mode” o To request an editable PPT version of this presentation, send a request to -

Palestine 100 Years of Struggle: the Most Important Events Yasser

Palestine 100 Years of Struggle: The Most Important Events Yasser Arafat Foundation 1 Early 20th Century - The total population of Palestine is estimated at 600,000, including approximately 36,000 of the Jewish faith, most of whom immigrated to Palestine for purely religious reasons, the remainder Muslims and Christians, all living and praying side by side. 1901 - The Zionist Organization (later called the World Zionist Organization [WZO]) founded during the First Zionist Congress held in Basel Switzerland in 1897, establishes the “Jewish National Fund” for the purpose of purchasing land in Palestine. 1902 - Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid II agrees to receives Theodor Herzl, the founder of the Zionist movement and, despite Herzl’s offer to pay off the debt of the Empire, decisively rejects the idea of Zionist settlement in Palestine. - A majority of the delegates at The Fifth Zionist Congress view with favor the British offer to allocate part of the lands of Uganda for the settlement of Jews. However, the offer was rejected the following year. 2 1904 - A wave of Jewish immigrants, mainly from Russia and Poland, begins to arrive in Palestine, settling in agricultural areas. 1909 Jewish immigrants establish the city of “Tel Aviv” on the outskirts of Jaffa. 1914 - The First World War begins. - - The Jewish population in Palestine grows to 59,000, of a total population of 657,000. 1915- 1916 - In correspondence between Sir Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner in Egypt, and Sharif Hussein of Mecca, wherein Hussein demands the “independence of the Arab States”, specifying the boundaries of the territories within the Ottoman rule at the time, which clearly includes Palestine. -

Avoiding Another War Between Israel and Hezbollah

COUNTING THE COST Avoiding Another War between Israel and Hezbollah By Nicholas Blanford and Assaf Orion “He who wishes to fight must first count the cost.” Sun Tzu, The Art of War ABOUT THE SCOWCROFT MIDDLE EAST SECURITY INITIATIVE The Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative honors the legacy of Brent Scowcroft and his tireless efforts to build a new security architecture for the region. Our work in this area addresses the full range of security threats and challenges including the danger of interstate warfare, the role of terrorist groups and other nonstate actors, and the underlying security threats facing countries in the region. Through all of the Council’s Middle East programming, we work with allies and partners in Europe and the wider Middle East to protect US interests, build peace and security, and unlock the human potential of the region. You can read more about our programs at www.atlanticcouncil.org/ programs/middle-east-programs/. May 2020 ISBN-13: 978-1-61977-099-7 This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. This report is made possible by general support to the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. COUNTING THE COST Avoiding Another War between Israel and Hezbollah CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .................................................................................................2 -

For Free Distribution Not for Sale

For Free Distribution Not For Sale January 2010 - no.06 Editorial Understanding UNIFIL three years on At the launch of ‘Al-Janoub’ in 2007 we hoped to have it serve as a platform for exchange of information between UNIFIL and the people of south Lebanon. We believed, and still do, that human relationships are best founded on a well informed appreciation of mutual concerns and sensibilities. Now, more than three years since the UN Security UNIFIL must therefore blow the whistle every time there is Council resolution 1701, the need remains more than any side violating any element of their agreement on the ever for UNIFIL to explain to the people what the cessation of hostilities. UNIFIL does this in an impartial mission is about and to in turn better understand the and factual manner, making its observations with full needs and expectations of the people. One would think transparency and ultimately deferring the judgment to the that after more than three decades of UNIFIL’s existence UN Security Council. [since 1978], the Lebanese would know all there is to Third, UNIFIL is NOT the agency that has primary know about it. However, the situation over these years responsibility for security in south Lebanon: the has evolved and so has UNIFIL. Lebanese Army is. Having facilitated the deployment Perceptions carried forward from the long years of of the Lebanese Army in south Lebanon, UNIFIL now presence, multiple UN involvement on issues related to, supports the Lebanese Army in ensuring security in the but often outside, UNIFIL’s remit and the plethora of UN area. -

New Book on Revisionist-Zionist Terrorists

New Book on Revisionist-Zionist Terrorists Thomas G. Mitchell, Ph.D., an independent scholar, is an occasional contributor to our blog. His newest books are “Likud Leaders” (McFarland, 2015) and “Israel’s Security Men” (McFarland, 2015). Dr. Mitchell’s review (below), embeds Bruce Hoffman’s new book in an ongoing discussion on how important the terror/guerrilla campaigns of the two Revisionist Zionist undergrounds were in the creation of Israel. Hoffman, as well as Tablet reviewer Adam Kirsch, hedge their bets somewhat, but suggest that these terror attacks were crucial; Tom Segev, who reviewed it for the NY Times, is doubtful. Anonymous Soldiers: The Struggle for Israel 1917-47 By Bruce Hoffman, Alfred A. Knopf, 618 pp. (484 pp. of text), $35 ($25.41 on Amazon). International terrorism expert Bruce Hoffman has chosen to write a book about the exploits of the Irgun Zvai Leumi (the Irgun or Etzel) and Lehi (Stern Group) in driving the British out of Palestine in the 1940s. Why should Hoffman have spent his time researching and writing this book and why should you spend your time reading it? First, Palestine is a classic example of a victorious strategy of urban guerrilla warfare, much like Ireland from 1919 to 1921. From the mid-1950s to the early 1970s, Menahem Begin’s memoir of his life as an underground leader, The Revolt, was almost required reading for revolutionary leaders in British colonies and had a major influence with EOKA in Cyprus and the IRA in Northern Ireland. Second, Hoffman’s book tells the story of the origins of the Israeli- Palestinian conflict, which is still with us today. -

Netanyahu's Annexation Plan Can't Be Stopped by Efraim Inbar

Netanyahu's Annexation Plan Can't Be Stopped by Efraim Inbar April 29, 2020 https://www.meforum.org/60838/netanyahu-annexation-plan-cant-be-stopped Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's plan to annex the Jordan Valley is not just a far-right wish, but the fulxllment of long- standing Israeli security objectives. Further, despite alarms by Netanyahu's critics in the United States and elsewhere about the plan, there is Annexation of the Jordan Valley is a long-standing objective actually widespread attracting widespread agreement among Israelis. agreement among Israelis about the strategic importance of the valley. That's why Blue and White leader Benny Gantz could sign off on the deal to form an emergency government. The consensus extends to Labor and even members of the opposition to the new national unity government. The extension of Israeli law to the Jordan Valley is in accordance with former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin's strategic tenets (the Allon Plan). Notably, more Israelis view the Jordan Valley as an indispensable defensible border than the Golan Heights. Defensible borders are More Israelis view the Jordan particularly necessary considering that the threats to Valley as indispensable than the Israel's population centers and Golan Heights. its strategic installations have increased in the 21st century. Iran hopes to establish a "Shiite Crescent" from the Gulf, via Iraq, Lebanon and Syria to the Mediterranean. Iran's objective is to turn Syria, Lebanon and Iraq into launching pads for missile and terror attacks against Israel. Iran also plans to destabilize the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and create a land bridge to the Palestinian Authority (close to Israel's heartland) in order to enhance its ability to harm Israel.