Settling Area C: the Jordan Valley Exposed 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Report: T I O 28N FebruaryS – 6 March 2007 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 28 February – 6 March 2007 Of note this week The IDF imposed a total closure on the West Bank during the Jewish holiday of Purim between 2 – 5 March. The closure prevented Palestinians, including workers, with valid permits, from accessing East Jerusalem and Israel during the four days. It is a year – the start of the 2006 Purim holiday – since Palestinian workers from the Gaza Strip have been prevented from accessing jobs in Israel. West Bank: − On 28 February, the IDF re-entered Nablus for one day to continue its largest scale operation for three years, codenamed ‘Hot Winter’. This second phase of the operation again saw a curfew imposed on the Old City, the occupation of schools and homes and house-to-house searches. The IDF also surrounded the three major hospitals in the area and checked all Palestinians entering and leaving. According to the Nablus Municipality 284 shops were damaged during the course of the operation. − Israeli Security Forces were on high alert in and around the Old city of Jerusalem in anticipation of further demonstrations and clashes following Friday Prayers at Al Aqsa mosque. Due to the Jewish holiday of Purim over the weekend, the Israeli authorities declared a blanket closure from Friday 2 March until the morning of Tuesday 6 March and all major roads leading to the Old City were blocked. -

Yitzhar – a Case Study Settler Violence As a Vehicle for Taking Over Palestinian Land with State and Military Backing

Yitzhar – A Case Study Settler violence as a vehicle for taking over Palestinian land with state and military backing August 2018 Yitzhar – A Case Study Settler violence as a vehicle for taking over Palestinian land with state and military backing Position paper, August 2018 Research and writing: Yonatan Kanonich Editing: Ziv Stahl Additional Editing: Lior Amihai, Miryam Wijler Legal advice: Atty. Michael Sfard, Atty. Ishai Shneidor Graphic design: Yuda Dery Studio English translation: Maya Johnston English editing: Shani Ganiel Yesh Din Public council: Adv. Abeer Baker, Hanna Barag, Dan Bavly, Prof. Naomi Chazan, Ruth Cheshin, Akiva Eldar, Prof. Rachel Elior, Dani Karavan, Adv. Yehudit Karp, Paul Kedar, Dr. Roy Peled, Prof. Uzy Smilansky, Joshua Sobol, Prof. Zeev Sternhell, Yair Rotlevy. Yesh Din Volunteers: Rachel Afek, Dahlia Amit, Maya Bailey, Hanna Barag, Michal Barak, Atty. Dr. Assnat Bartor, Osnat Ben-Shachar, Rochale Chayut, Beli Deutch, Dr. Yehudit Elkana, Rony Gilboa, Hana Gottlieb, Tami Gross, Chen Haklai, Dina Hecht, Niva Inbar, Daniel A. Kahn, Edna Kaldor, Nurit Karlin, Ruth Kedar, Lilach Klein Dolev, Dr. Joel Klemes, Bentzi Laor, Yoram Lehmann RIP, Judy Lots, Aryeh Magal, Sarah Marliss, Shmuel Nachmully RIP, Amir Pansky, Talia Pecker Berio, Nava Polak, Dr. Nura Resh, Yael Rokni, Maya Rothschild, Eddie Saar, Idit Schlesinger, Ilana Meki Shapira, Dr. Tzvia Shapira, Dr. Hadas Shintel, Ayala Sussmann, Sara Toledano. Yesh Din Staff: Firas Alami, Lior Amihai, Yudit Avidor, Maysoon Badawi, Hagai Benziman, Atty. Sophia Brodsky, Mourad Jadallah, Moneer Kadus, Yonatan Kanonich, Atty. Michal Pasovsky, Atty. Michael Sfard, Atty. Muhammed Shuqier, Ziv Stahl, Alex Vinokorov, Sharona Weiss, Miryam Wijler, Atty. Shlomy Zachary, Atty. -

E Items-In-Middle East - Country Files - Jordan

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page Date 14/06/2006 Time 9:23:28 AM S-0899-0009-03-00001 Expanded Number S-0899-0009-03-00001 ™e Items-in-Middle East - country files - Jordan Date Created 23/02/1979 Record Type Archival Item Container s-0899-0009: Peacekeeping - Middle East 1945-1981 Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit sr Room No. — No de bureau Extension - Poste Date *" \\ ^— — 17 Dec. 1980 . FOR ACTION POUR SUITE A DONNER FOR APPROVAL X POUR APPROBATION FOR SIGNATURE X POUR SIGNATURE FOR COMMENTS POUR OBSERVATIONS MAY WE DISCUSS? POURRIONS-NOUS EN PARLER ? YOUR ATTENTION VOTRE ATTENTION AS DISCUSSED COMME CONVENU AS REQUESTED SUITE A VOTRE DEMANDE NOTE AND RETURN NOTER ET RETOURNER FOR INFORMATION POUR INFORMATION COM.6 (a-7B) THE SECRETARY-GENERAL 19 December 1980 Excellency, I wish to refer to your lette^" of 11 December 1980 and to your statement in riom: of reply in the plenary on 16 December concerning your objections to certain recent press releases/Issued by the Department of Public Information. In accordance with assurance given through the President of the Genera I have had both instances thoroughly restigated by Mr. Yasushi Akashi, Under-Secreta -General for Public Information, I have been informe the results of this investigation, and Mr. Akashi hasywritten to you in detail of his findings, As Mr. Akashi has already told you, these inaccuracies arose from inadvertent mistakes and the necessary steps have been taken to prevent their repetition. I sincerely hope that the? matter has therefore been clarified to your full satisfaction and I very much regret the trouble and inconvenience these unfortunate occurrences have caused you. -

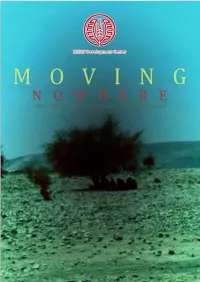

Moving-Nowhere.Pdf

MA’AN Development Center MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 1 2 MOVINGMOVING NOWHERE: FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY NOWHERE FIRING ZONES AND FORCIBLE TRANSFER IN THE JORDAN VALLEY 2015 3 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Physical Security 6 Eviction Orders And Demolition Orders 10 Psychological Security 18 Livelihood Reductions 22 Environmental Concerns 24 Water 26 Settler Violence 28 Isuues Faced By Other Communities In Area C 32 International Humanitarian Law 36 Conclusion 40 Photo by Hamza Zbiedat Hamza by Photo 4 Moving Nowhere Introduction Indirect and direct forcible transfer is currently at the forefront of Israel’s ideological agenda in area C. Firing zones, initially established as a means of land control, are now being used to create an environment so hostile that Palestinians are forced to leave the area or live in conditions of deteriorating security. re-dating the creation of the state of Israel, there was an ideological agenda within Pcertain political spheres predicated on the notion that Israel should exist from the sea to the Jordan River. Upon creation of the State the subsequent governments sought to establish this notion. This has resulted in an uncompromising programme of colonisation, ethnic cleansing and de-development in Palestine. The conclusion of the six day war in 1967 marked the beginning of the ongoing occupation, under which the full force of the ideological agenda has been extended into the West Bank. Israel has continuously led projects and policies designed to appropriate vast amounts of Palestinian land in the West Bank, despite such actions being illegal under international law. -

Palestine Divided

Update Briefing Middle East Briefing N°25 Ramallah/Gaza/Brussels, 17 December 2008 Palestine Divided I. OVERVIEW Hamas, by contrast, is looking to gain recognition and legitimacy, pry open the PLO and lessen pressure against the movement in the West Bank. Loath to con- The current reconciliation process between the Islamic cede control of Gaza, it is resolutely opposed to doing Resistance Movement (Hamas) and Palestinian National so without a guaranteed strategic quid pro quo. Liberation Movement (Fatah) is a continuation of their struggle through other means. The goals pursued by the The gap between the two movements has increased over two movements are domestic and regional legitimacy, time. What was possible two years or even one year together with consolidation of territorial control – not ago has become far more difficult today. In January national unity. This is understandable. At this stage, both 2006 President Abbas evinced some flexibility. That parties see greater cost than reward in a compromise quality is now in significantly shorter supply. Fatah’s that would entail loss of Gaza for one and an uncom- humiliating defeat in Gaza and Hamas’s bloody tac- fortable partnership coupled with an Islamist foothold tics have hardened the president’s and Fatah’s stance; in the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) for the moreover, despite slower than hoped for progress in other. Regionally, Syria – still under pressure from the West Bank and inconclusive political negotiations Washington and others in the Arab world – has little with Israel, the president and his colleagues believe incentive today to press Hamas to compromise, while their situation is improving. -

Zawata Village Profile

Zawata Village Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2014 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Nablus Governorate. These booklets came about as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in the Nablus Governorate, and aim to depict the overall living conditions in the governorate and present developmental plans to assist in improving the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the programs and activities needed to mitigate the impact of the current insecure political, economic and social conditions in the Nablus Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in the Nablus Governorate. -

Netanyahu's Annexation Plan Can't Be Stopped by Efraim Inbar

Netanyahu's Annexation Plan Can't Be Stopped by Efraim Inbar April 29, 2020 https://www.meforum.org/60838/netanyahu-annexation-plan-cant-be-stopped Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's plan to annex the Jordan Valley is not just a far-right wish, but the fulxllment of long- standing Israeli security objectives. Further, despite alarms by Netanyahu's critics in the United States and elsewhere about the plan, there is Annexation of the Jordan Valley is a long-standing objective actually widespread attracting widespread agreement among Israelis. agreement among Israelis about the strategic importance of the valley. That's why Blue and White leader Benny Gantz could sign off on the deal to form an emergency government. The consensus extends to Labor and even members of the opposition to the new national unity government. The extension of Israeli law to the Jordan Valley is in accordance with former Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin's strategic tenets (the Allon Plan). Notably, more Israelis view the Jordan Valley as an indispensable defensible border than the Golan Heights. Defensible borders are More Israelis view the Jordan particularly necessary considering that the threats to Valley as indispensable than the Israel's population centers and Golan Heights. its strategic installations have increased in the 21st century. Iran hopes to establish a "Shiite Crescent" from the Gulf, via Iraq, Lebanon and Syria to the Mediterranean. Iran's objective is to turn Syria, Lebanon and Iraq into launching pads for missile and terror attacks against Israel. Iran also plans to destabilize the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and create a land bridge to the Palestinian Authority (close to Israel's heartland) in order to enhance its ability to harm Israel. -

Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict

Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict September 2000 - September 2007 L_C089061 Table of Contents: Foreword...........................................................................................................................1 Suicide Terrorists - Personal Characteristics................................................................2 Suicide Terrorists Over 7 Years of Conflict - Geographical Data...............................3 Suicide Attacks since the Beginning of the Conflict.....................................................5 L_C089062 Israeli Security Agency [logo] Suicide Terrorists in the Current Conflict Foreword Since September 2000, the State of Israel has been in a violent and ongoing conflict with the Palestinians, in which the Palestinian side, including its various organizations, has carried out attacks against Israeli citizens and residents. During this period, over 27,000 attacks against Israeli citizens and residents have been recorded, and over 1000 Israeli citizens and residents have lost their lives in these attacks. Out of these, 155 (May 2007) attacks were suicide bombings, carried out against Israeli targets by 178 (August 2007) suicide terrorists (male and female). (It should be noted that from 1993 up to the beginning of the conflict in September 2000, 38 suicide bombings were carried out by 43 suicide terrorists). Despite the fact that suicide bombings constitute 0.6% of all attacks carried out against Israel since the beginning of the conflict, the number of fatalities in these attacks is around half of the total number of fatalities, making suicide bombings the most deadly attacks. From the beginning of the conflict up to August 2007, there have been 549 fatalities and 3717 casualties as a result of 155 suicide bombings. Over the years, suicide bombing terrorism has become the Palestinians’ leading weapon, while initially bearing an ideological nature in claiming legitimate opposition to the occupation. -

B'tselem Report: Dispossession & Exploitation: Israel's Policy in the Jordan Valley & Northern Dead Sea, May

Dispossession & Exploitation Israel's policy in the Jordan Valley & northern Dead Sea May 2011 Researched and written by Eyal Hareuveni Edited by Yael Stein Data coordination by Atef Abu a-Rub, Wassim Ghantous, Tamar Gonen, Iyad Hadad, Kareem Jubran, Noam Raz Geographic data processing by Shai Efrati B'Tselem thanks Salwa Alinat, Kav LaOved’s former coordinator of Palestinian fieldworkers in the settlements, Daphna Banai, of Machsom Watch, Hagit Ofran, Peace Now’s Settlements Watch coordinator, Dror Etkes, and Alon Cohen-Lifshitz and Nir Shalev, of Bimkom. 2 Table of contents Introduction......................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter One: Statistics........................................................................................................ 8 Land area and borders of the Jordan Valley and northern Dead Sea area....................... 8 Palestinian population in the Jordan Valley .................................................................... 9 Settlements and the settler population........................................................................... 10 Land area of the settlements .......................................................................................... 13 Chapter Two: Taking control of land................................................................................ 15 Theft of private Palestinian land and transfer to settlements......................................... 15 Seizure of land for “military needs”............................................................................. -

Mapping Peace Between Syria and Israel

UNiteD StateS iNStitUte of peaCe www.usip.org SpeCial REPORT 1200 17th Street NW • Washington, DC 20036 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPO R T Frederic C. Hof Commissioned in mid-2008 by the United States Institute of Peace’s Center for Mediation and Conflict Resolution, this report builds upon two previous groundbreaking works by the author that deal with the obstacles to Syrian- Israeli peace and propose potential ways around them: a 1999 Middle East Insight monograph that defined the Mapping peace between phrase “line of June 4, 1967” in its Israeli-Syrian context, and a 2002 Israel-Syria “Treaty of Peace” drafted for the International Crisis Group. Both works are published Syria and israel online at www.usip.org as companion pieces to this report and expand upon a concept first broached by the author in his 1999 monograph: a Jordan Valley–Golan Heights Environmental Preserve under Syrian sovereignty that Summary would protect key water resources and facilitate Syrian- • Syrian-Israeli “proximity” peace talks orchestrated by Turkey in 2008 revived a Israeli people-to-people contacts. long-dormant track of the Arab-Israeli peace process. Although the talks were sus- Frederic C. Hof is the CEO of AALC, Ltd., an Arlington, pended because of Israeli military operations in the Gaza Strip, Israeli-Syrian peace Virginia, international business consulting firm. He directed might well facilitate a Palestinian state at peace with Israel. the field operations of the Sharm El-Sheikh (Mitchell) Fact- Finding Committee in 2001. • Syria’s “bottom line” for peace with Israel is the return of all the land seized from it by Israel in June 1967. -

Einabus Village Profile

Einabus Village Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2014 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Nablus Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Nablus Governorate. These booklets came about as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in the Nablus Governorate, which aims to depict the overall living conditions in the governorate and present developmental plans to assist in improving the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Nablus Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in Nablus Governorate. -

Made in Israel: Agricultural Exports from Occupied Territories

Agricultural Made in Exports from Israel Occupied Territories April 2014 Agricultural Made in Exports from Israel Occupied Territories April 2014 The Coalition of Women for Peace was established by bringing together ten feminist peace organizations and non-affiliated activist women in Israel. Founded soon after the outbreak of the Second Intifada in 2000, CWP today is a leading voice against the occupation, committed to feminist principles of organization and Jewish-Palestinian partnership, in a relentless struggle for a just society. CWP continuously voices a critical position against militarism and advocates for radical social and political change. Its work includes direct action and public campaigning in Israel and internationally, a pioneering investigative project exposing the occupation industry, outreach to Israeli audiences and political empowerment of women across communities and capacity-building and support for grassroots activists and initiatives for peace and justice. www.coalitionofwomen.org | [email protected] Who Profits from the Occupation is a research center dedicated to exposing the commercial involvement of Israeli and international companies in the continued Israeli control over Palestinian and Syrian land. Currently, we focus on three main areas of corporate involvement in the occupation: the settlement industry, economic exploitation and control over population. Who Profits operates an online database which includes information concerning companies that are commercially complicit in the occupation. Moreover, the center publishes in-depth reports and flash reports about industries, projects and specific companies. Who Profits also serves as an information center for queries regarding corporate involvement in the occupation – from individuals and civil society organizations working to end the Israeli occupation and to promote international law, corporate social responsibility, social justice and labor rights.