Defamation Via Hyperlinks: More Than Meets the Eye Gary Kok Yew CHAN Singapore Management University, [email protected]

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Publications for Gregory Tolhurst 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014

Publications for Gregory Tolhurst 2019 High Court of Australia. Journal of Contract Law, 32(3), 203- Pearson, G., Peden, E., Tolhurst, G., Paterson, J., McCracken, 230. S., McNaughton, A., Catterwell, R., Silink, A. (2019). Atkinson, S., Tolhurst, G., Hossain, L. (2015). The Dichotomy Commercial Law: Commentary & Materials - 4th Edition. of Decision Sciences in Information Assurance, Privacy, and Sydney: Thomson Lawbook Co. (Thomson Reuters). Security Applications in Law and Joint Ventures. International 2018 Journal on Advances in Security, 8(3&4), 141-152. <a href="http://www.iariajournals.org/security/sec_v8_n34_2015_p Carter, J., Courtney, W., Tolhurst, G. (2018). Two models for aged.pdf">[More Information]</a> discharge of a contract by repudiation. Cambridge Law Journal, Carter, J., Tolhurst, G. (2015). The Modern Meaning of Joint 77(1), 97-123. <a Venture Terms. In Tony Damian, J.W. Carter (Eds.), Before href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0008197317000836">[More You Tie the Knot: Commercial issues in joint venture law, (pp. Information]</a> 75-122). Australia: Ross Parsons Centre of Commercial, 2017 Corporate and Taxation Law. Carter, J., Courtney, W., Tolhurst, G. (2017). An Assimilated McCracken, S., Stumbles, J., Tolhurst, G. (2015). Title Transfer Approach to Discharge for Breach of Contract by Delay. Collateral Arrangements under the Personal Property Securities Cambridge Law Journal, 76(1), 63-86. <a Act 2009 (Cth): Paper I Setting the Scene. Journal of Contract href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0008197316000830">[More Law, 33(1), 1-19. Information]</a> McCracken, S., Stumbles, J., Tolhurst, G. (2015). Title Transfer Carter, J., Courtney, W., Tolhurst, G. (2017). Assessment of Collateral Arrangements under the Personal Property Securities Contractual Penalties: Dunlop Deflated. -

SAMPLE Content Directory

SAMPLE Nearly 1,300 Journals Content Directory Participating! http://heinonline.org Please Note: This is a list of ALL content available in our two main library modules through the HeinOnline interface. Due to the various subscription packages available, access to this content may vary. TABLE OF CONTENTS: Law Journal Library ..................................................................................................................................... pp. 1-25 Legal Classics Library................................................................................................................................. pp. 26-56 LAW JOURNAL LIBRARY VOLUMES YEARS Acta Juridica 1958-2003 1958-2003 Acta Universitatis Lucian Blaga 2001-2005 2001-2005 Adelaide Law Review 1-24 1960-2003 Administrative Law Journal of the American University† 1-10 1987-1996 Administrative Law Review (ABA) 1-57 1949-2005 Advocate: A Weekly Law Journal† 1-2 1888-1890 African Human Rights Law Journal 1-3 2001-2003 African Journal of Legal Studies 1 2004-2005 Air Force Law Review 1-58 1959-2006 Air Law Review † 1-12 1930-1941 Akron Law Review 1-38 1967-2005 Akron Tax Journal 1-21 1983-2006 Alabama Law Journal (Birmingham) † 1-5 1925-1930 Alabama Law Journal (Montgomery) † 1-4 1882-1885 Alabama Law Review *JUST UPDATED* 1-57 1948-2006 Alaska Law Review 1-22 1984-2005 Albany Law Environmental Outlook Journal 1-10 1995-2005 Albany Law Journal † 1-70 1870-1909 Albany Law Journal of Science and Technology 1-15 1991-2005 Albany Law Review 1-69 1931-2006 Alberta Law Quarterly -

Journal Title Publisher ISSN ISSN Online Year Inception Field Of

Current at 6 December 2019 Year Field of Journal Title Publisher ISSN ISSN Online Inception Research 2019 Rating 4OR Springer Nature 1619-4500 1614-2411 2003 1503 B AACE International Transactions AACE International 1528-7106 1528-7106 1967 1503 B Abacus Wiley-Blackwell Publishing 0001-3072 1467-6281 1965 1501 A Institute of Economics, Academia Economic Papers Academia Sinica 1018-161X 1973 1402 C Academy of Accounting and Financial Academy of Accounting and 1096-3685 1997 C Studies Journal Financial Studies 1501 Academy of Management Annals Academy of Management 1941-6520 1941-6067 2008 1503 A* Academy of Management Discoveries Academy of Management 2168-1007 2015 1503 A Academy of Management Journal Academy of Management 0001-4273 1948-0989 1958 1503 A* Academy of Management Learning and Education Academy of Management 1537-260X 1944-9585 2002 1503 A* Academy of Management Perspectives Academy of Management 1558-9080 1943-4529 1987 1503 A Academy of Management Review Academy of Management 0363-7425 1930-3807 1976 1503 A* Jordan Whitney Enterprises, Academy of Marketing Studies Journal Inc 1095-6298 1095-6298 1980 1505 B Accident Analysis and Prevention Elsevier 0001-4575 1879-2057 1969 1507 A* Accountancy Business and the Public Association for Accountancy 1745-7718 2002 B Interest & Business Affairs 1501 Accounting Accountability and Performance Griffith University 1445-954X 1995 C 1501 Accounting and Business Research Taylor & Francis Online 0001-4788 2159-4260 1970 1501 A Year Field of Journal Title Publisher ISSN ISSN Online Inception -

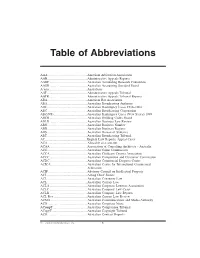

Thomson Reuters 1 Table of Abbreviations

Table of Abbreviations AAA ................................................American Arbitration Association AAR.................................................Administrative Appeals Reports AARF ..............................................Australian Accounting Research Foundation AASB ..............................................Australian Accounting Standard Board A’asia...............................................Australasia AAT .................................................Administrative Appeals Tribunal AATR...............................................Administrative Appeals Tribunal Reports ABA.................................................American Bar Association ABA.................................................Australian Broadcasting Authority ABC.................................................Australian Bankruptcy Cases 1928–1964 ABC.................................................Australian Broadcasting Corporation ABC(NS) .........................................Australian Bankruptcy Cases (New Series) 1999– ABCB ..............................................Australian Building Codes Board ABLR ..............................................Australian Business Law Review ABN.................................................Australian Business Number ABR.................................................Australian Business Register ABS .................................................Australian Bureau of Statistics ABT .................................................Australian Broadcasting Tribunal AC....................................................English -

LDS List of Publications

LIONEL D. SMITH List of Publications 3 February 2016 q Books Waters’ Law of Trusts in Canada, 4th edition; with Donovan Waters and Mark Gillen (Toronto: Thomson/Carswell, 2012). As in the 3rd edition (2005), I was responsible for chapters 10-11, 17-21, 23-30, and the appendices. Canadian Corporate Law: Cases, Notes and Materials, 4th edition; with Bruce Welling and Leonard Rotman (Toronto: LexisNexis Canada, 2010). In this edition, I was responsible for Chapters 5, 6, and 7. I also participated, with different responsibilities and co-authors, in the first (1996), second (2001) and third (2006) editions. Oosterhoff on Trusts: Text, Commentary and Materials, 7th edition; with Albert Oosterhoff, Robert Chambers, and Mitchell McInnes (Toronto: Thomson/Carswell, 2009). In this edition, I was responsible for Chapters 1, 10 and 15. I also participated, with different responsibilities, in the 6th edition (2004). Commercial Trusts in European Private Law; with Michele Graziadei and Ugo Mattei (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005; paperback edition, 2009). The three co-authors wrote together sections 1 and 2 in Part I, and Part III, and edited the book, to which there were 22 other contributors. I am the sole author of the sections on English law. Reviews: (2006), 31 European Law Review 608; (2006), 20 Trust Law International 284; (2007), 11 Edinburgh Law Review 135. The Law of Restitution in Canada: Cases, Notes and Materials; with Robert Chambers, Mitchell McInnes, Jason Neyers and Stephen Pitel (Toronto: Emond Montgomery, 2004). I was responsible for Chapters 1, 2, 3, 6, 7 and 8. The Law of Tracing (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997). -

Thomson Reuters Westlaw India

Thomson Reuters Westlaw India Our innovative technology sets us apart from other legal research systems, giving legal professionals the power to do more with less. THOMSON REUTERS WESTLAWTM INDIA THOMSON REUTERS WESTLAW INDIA Contents Secondary Materials Highlights International Law Libraries ................................................................2 United States Materials .......................................................................5 • Contains more than 1,200 law reviews & journals True prints of cases available for: from around the world Secondary Materials Highlights .......................................................3 Indian Content: Cases ...........................................................................6 • Admiralty and Ecclesiastical Cases (1865-75) L.R. A. & E. • Includes legal encyclopedias such as American UK Journals ................................................................................................4 Indian Content: Legislation ...............................................................6 • Appeal Cases (1875-90) L.R. App. Cas Jurisprudence & Corpus Juris Secundum® Commonwealth Libraries ...................................................................4 Special Features on Westlaw India ................................................ 7 • Appeal Cases (1891-present) A.C. • Black’s Law Dictionary® EU Content .................................................................................................4 • Business Law Reports (1972-Present) • Chancery Appeals (1865-75) L.R. -

Corporate Defamation in English Law: Corporate Reputation, Freedom of Speech, and the Defamation Act 2013

CORPORATE DEFAMATION IN ENGLISH LAW: CORPORATE REPUTATION, FREEDOM OF SPEECH, AND THE DEFAMATION ACT 2013 David Jackman Acheson January 2020. This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of the University of Portsmouth. Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. Word count: 80,445. FORM UPR16 Research Ethics Review Checklist Please include this completed form as an appendix to your thesis (see the Research Degrees Operational Handbook for more information Postgraduate Research Student (PGRS) Information Student ID: 387767 PGRS Name: David Jackman Acheson Department: Law First Supervisor: Daniel Bedford Start Date: September 2013 (or progression date for Prof Doc students) Study Mode and Route: Part-time MPhil MD Full-time PhD Professional Doctorate Title of Thesis: Corporate Defamation in English Law: Corporate Reputation, Freedom of Speech, and the Defamation Act 2013 Thesis Word Count: 80445 (excluding ancillary data) If you are unsure about any of the following, please contact the local representative on your Faculty Ethics Committee for advice. Please note that it is your responsibility to follow the University’s Ethics Policy and any relevant University, academic or professional guidelines in the conduct of your study Although the Ethics Committee may have given your study a favourable opinion, the final responsibility for the ethical conduct of this work lies with the researcher(s). -

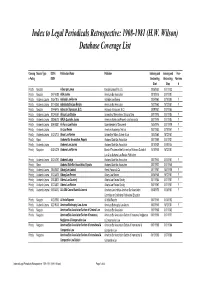

Index to Legal Periodicals Retrospective: 1908-1981 (H.W. Wilson) Database Coverage List

Index to Legal Periodicals Retrospective: 1908-1981 (H.W. Wilson) Database Coverage List Coverag Source Type ISSN / Publication Name Publisher Indexing and Indexing and Peer- e Policy ISBN Abstracting Abstracting Reviewe Start Stop d Priority Magazine A Georgia Lawyer Georgia Lawyer Pub. Co. 01/08/1930 01/01/1932 Priority Magazine 0747-0088 ABA Journal American Bar Association 01/10/1915 01/07/1981 Priority Academic Journal 0065-1915 Adelaide Law Review Adelaide Law Review 01/04/1960 01/10/1980 Y Priority Academic Journal 0001-8368 Administrative Law Review American Bar Association 15/07/1963 15/12/1981 Y Priority Magazine 0044-6416 Advocate (Vancouver, B.C.). Advocate (Vancouver, B.C.). 01/09/1952 01/07/1960 Priority Academic Journal 0002-0060 African Law Studies University of Birmingham, School of Law 01/01/1975 01/01/1980 Y Priority Academic Journal 0883-6078 AIPLA Quarterly Journal American Intellectual Property Law Association 01/01/1976 01/01/1980 Y Priority Academic Journal 0094-8381 Air Force Law Review Superintendent of Documents 15/04/1974 01/01/1979 Y Priority Academic Journal Air Law Review American Academy of Air Law 01/01/1930 01/10/1941 Y Priority Academic Journal 0002-371X Akron Law Review University of Akron, School of Law 15/04/1968 15/12/1981 Priority Report Alabama Bar Association, Reports Alabama State Bar Association 01/01/1909 01/01/1921 Priority Academic Journal Alabama Law Journal Alabama State Bar Association 01/10/1925 01/05/1930 Priority Magazine 0002-4279 Alabama Law Review Board of Trustees of the University of Alabama School of 15/10/1948 15/12/1981 Law & its Alabama Law Review Publication Priority Academic Journal 0002-4287 Alabama Lawyer Alabama State Bar Association 01/01/1940 01/04/1981 Y Priority Report Alabama State Bar Association, Reports Alabama State Bar Association 01/01/1922 01/01/1948 Priority Academic Journal 2154-8552 Albany Law Journal Weed, Parsons & Co. -

2825A Law Quarterly Review Legal Obligations and Legal

2825A LAW QUARTERLY REVIEW LEGAL OBLIGATIONS AND LEGAL REVOLUTIONS The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG LAW QUARTERLY REVIEW LEGAL OBLIGATIONS AND LEGAL REVOLUTIONS* The Hon. Michael Kirby AC CMG** ABSTRACT In this article, the author reviews changes he has seen in the law over 34 years of judicial service in Australia. He identifies ten ‘revolutions’: 1) the decline in the influence of English courts and the rise of disunity in the common law; 2) the growing impact of European and human rights law, but not in Australia; 3) the increasing sensitivity to discrimination and unequal treatment in the law; 4) the reduction of acceptance of formalism; 5) the growth in comparative law analysis; 6) the recognition of the limits to pure realism; 7) the decline in jury trial; 8) the increase in statutory law at the cost of the common law; 9) the importation of statutory limits on civil recovery; and 10) the recognition of the need for values in the law. Many of the developments in contemporary law were not mentioned, or even perceived, 50 years ago. The author concludes that there is no reason to believe that the legal revolutions will abate; raising the question about the coming revolutions that we do not yet recognise. I served as a judge in Australia for 34 years.1 For good measure, I was commissioned in Solomon Islands concurrently for 3 years.2 The * Paper for Obligations VIII, Cambridge University, England, 19-21 July 2016. The author thanks Professor Sarah Worthington for the invitation and Dr James Goudkamp of Keble College, Oxford University, for many suggestions. -

Laura Isotalo SCIL Working Paper 6 FINAL for Publication

Scottish Centre for International Law Working Paper Series Climate Compatible Investment Treaty Law: The Role of Legitimate Expectations Laura Isotalo Working Paper No. 6 The purpose of the Scottish Centre for International Law Working Paper Series is to promote the dissemination of international legal scholarship produced by researchers associated with the Scottish Centre for International Law. The material contained in the papers will often be work in progress. Authors of the working papers would welcome comments and suggestions on the content of their papers. This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s). This paper may not be cited or quoted without the permission of the author. Scottish Centre for International Law Working Paper Series – Do not cite without the consent of the author Climate Compatible Investment Treaty Law: The Role of Legitimate Expectations Laura Isotalo* Abstract: This paper considers the interplay between investment treaty law and climate change regulation, recognising both the need to allow sufficient space for States to take measures against climate change as well as the role investment law has in protecting low- carbon investment. A particular point of focus is the principle of legitimate expectations as it appears in the standard of fair and equitable treatment. An attempt will be made to provide a coherent and suitable framework for the application of this principle, which also promotes compatibility with climate law. 1. Introduction It has been a growing concern for a while that the legal instruments adopted for the purpose of climate change mitigation are in tension with certain other areas of international law.1 International investment law is one such an area of tension, as the economic interests of investors may be affected by measures taken in an effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. -

Farewell Ceremony Address by the Honourable J J

FAREWELL CEREMONY ADDRESS BY THE HONOURABLE J J SPIGELMAN AC UPON THE OCCASION OF HIS RETIREMENT AS CHIEF JUSTICE OF NEW SOUTH WALES BANCO COURT, SYDNEY 31 MAY 2011 Your Excellency, your Honours, Attorney, fellow lawyers, ladies and gentlemen, you do me and the Court great honour by your attendance. The welcome to country with which this ceremony began has particular significance for me. As I think most people here will be aware, association with the cause of indigenous Australians has been an important part of my personal journey. The welcome has an additional symbolic significance. Just as the elders of the Gadigal clan of the Eora people have been the custodians of the land on which we meet, the 16 Chief Justices of New South Wales, including myself, have been the custodians of the institutional traditions of the rule of law, since this Court was established almost exactly 187 years ago. 1 Most people in this audience will have heard me speak, probably more than once, of the significance for our society of the longevity of our fundamental institutions of governance. It was a theme of my first address upon my swearing-in as Chief Justice. It has featured as a basic theme in the address I have given at each of the 400 ceremonies I have conducted for the admission of legal practitioners, during the course of which just over 23,000 lawyers were admitted. The point might by now seem belaboured, but it is a point worth belabouring. Many of you would have been present on the occasion of the ceremony to mark the Court’s 175 th Anniversary, in May 1999. -

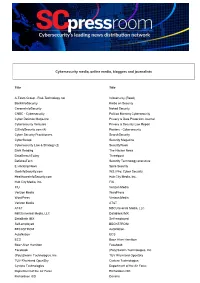

Cybersecurity Media, Online Media, Bloggers and Journalists

Cybersecurity media, online media, bloggers and journalists Title Title A-Team Group - Risk-Technology.net Infosecurity (Reed) BankInfoSecurity Krebs on Security CareersInfoSecurity Naked Security CNBC - Cybersecurity Politico Morning Cybersecurity Cyber Defence Magazine Privacy & Data Protection Journal Cybersecurity Ventures Privacy & Security Law Report CUInfoSecurity.com (4) Reuters - Cybersecurity Cyber Security Practitioners SearchSecurity CyberScoop Security Magazine Cybersecurity Law & Strategy (2) SecurityWeek Dark Reading The Hacker News DataBreachToday Threatpost DefenseTech Security Technology executive E Hacking News Spire Security GovInfoSecurity.com WSJ Pro: Cyber Security HealthcareInfoSecurity.com Hub City Media, Inc. Hub City Media, Inc. FIU FIU Verizon Media Verizon Media WordPress WordPress Verizon Media Verizon Media AT&T AT&T NBCUniversal Media, LLC NBCUniversal Media, LLC DataBank IMX DataBank IMX Self-employed Self-employed BECKSTROM BECKSTROM AutoNation AutoNation ECS ECS Booz Allen Hamilton Booz Allen Hamilton Facebook Facebook (Poly)Swarm Technologies, Inc. (Poly)Swarm Technologies, Inc. TUV Rheinland OpenSky TUV Rheinland OpenSky Cyxtera Technologies Cyxtera Technologies Department of the Air Force Department of the Air Force Richardson ISD Richardson ISD Dansha Dansha Prime Tech Partners Prime Tech Partners LookingGlass Cyber Solutions, Inc. LookingGlass Cyber Solutions, Inc. DataBlockChain DataBlockChain Knowledge Accelerators Knowledge Accelerators Transmosis Transmosis SpliceNet SpliceNet Protocol Labs