Farewell Ceremony Address by the Honourable J J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tasmanian ABC Production Unit Is an Invaluable Part of Media in Tasmania

The Tasmanian ABC Production Unit is an invaluable part of media in Tasmania. The following is an excerpt of the ABC Strategic Plan pertinent to the issue: ABC STRATEGIC PLAN 2010–13 page 9 Providing content and services of the highest quality lies at the heart of the ABC’s public purpose. Audiences expect the Corporation to offer experiences that are engaging, entertaining, informative and trustworthy; the ABC will meet these expectations. In particular, it remains committed to the creation and delivery of Australian content, services to local communities, the highest levels of editorial standards and multi-platform delivery of content. The Corporation’s ability to sustain and transform itself depends fundamentally on its processes and people. As a public service, it must constantly seek to maximise the efficiency and effectiveness of its operations, converting savings into its programs and services. At the same time, it is crucial that the ABC maintain and support a creative and adaptable workforce that is capable of meeting the demands of the future, and actively engage with the wider Australian creative community. The Production Unit in Tasmania fulfils all these criteria. Creation of local content that tells the unique stories of Tasmania. These stories can be made without the need to seek development funding. The ABC Production Unit is a highly qualified and experienced team – able to create quality content in a timely way that matches or betters private production. The ABC has long been an employer of emerging media people both in front of camera and in production. Camera/sound/editing. This is invaluable to support of media community in Tasmania. -

Publications for Gregory Tolhurst 2019 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014

Publications for Gregory Tolhurst 2019 High Court of Australia. Journal of Contract Law, 32(3), 203- Pearson, G., Peden, E., Tolhurst, G., Paterson, J., McCracken, 230. S., McNaughton, A., Catterwell, R., Silink, A. (2019). Atkinson, S., Tolhurst, G., Hossain, L. (2015). The Dichotomy Commercial Law: Commentary & Materials - 4th Edition. of Decision Sciences in Information Assurance, Privacy, and Sydney: Thomson Lawbook Co. (Thomson Reuters). Security Applications in Law and Joint Ventures. International 2018 Journal on Advances in Security, 8(3&4), 141-152. <a href="http://www.iariajournals.org/security/sec_v8_n34_2015_p Carter, J., Courtney, W., Tolhurst, G. (2018). Two models for aged.pdf">[More Information]</a> discharge of a contract by repudiation. Cambridge Law Journal, Carter, J., Tolhurst, G. (2015). The Modern Meaning of Joint 77(1), 97-123. <a Venture Terms. In Tony Damian, J.W. Carter (Eds.), Before href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0008197317000836">[More You Tie the Knot: Commercial issues in joint venture law, (pp. Information]</a> 75-122). Australia: Ross Parsons Centre of Commercial, 2017 Corporate and Taxation Law. Carter, J., Courtney, W., Tolhurst, G. (2017). An Assimilated McCracken, S., Stumbles, J., Tolhurst, G. (2015). Title Transfer Approach to Discharge for Breach of Contract by Delay. Collateral Arrangements under the Personal Property Securities Cambridge Law Journal, 76(1), 63-86. <a Act 2009 (Cth): Paper I Setting the Scene. Journal of Contract href="http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0008197316000830">[More Law, 33(1), 1-19. Information]</a> McCracken, S., Stumbles, J., Tolhurst, G. (2015). Title Transfer Carter, J., Courtney, W., Tolhurst, G. (2017). Assessment of Collateral Arrangements under the Personal Property Securities Contractual Penalties: Dunlop Deflated. -

Annual Report 2016–2017 National Library of Australia Annual Report 2016–2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2016–2017 REPORT ANNUAL NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA OF AUSTRALIA LIBRARY NATIONAL ANNUAL REPORT 2016–2017 NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA ANNUAL REPORT 2016–2017 NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA 4 August 2017 Senator the Hon. Mitch Fifield Minister for the Arts Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Minister National Library of Australia Annual Report 2016–2017 The Council, as the accountable authority of the National Library of Australia, has pleasure in submitting to you for presentation to each House of Parliament its annual report covering the period 1 July 2016 to 30 June 2017. Published by the National Library of Australia The Council approved this report at its meeting in Canberra on 4 August 2017. Parkes Place Canberra ACT 2600 The report is submitted to you in accordance with section 46 of the Public T 02 6262 1111 Governance and Performance and Accountability Act 2013. F 02 6257 1703 National Relay Service 133 677 We commend the Annual Report to you. nla.gov.au/policy/annual.html Yours sincerely ABN 28 346 858 075 © National Library of Australia 2017 ISSN 0313-1971 (print) 1443-2269 (online) National Library of Australia Mr Ryan Stokes Dr Marie-Louise Ayres Annual report / National Library of Australia.–8th (1967/68)– Chair of Council Director-General Canberra: NLA, 1968––v.; 25 cm. Annual. Continues: National Library of Australia. Council. Annual report of the Council = ISSN 0069-0082. Report year ends 30 June. ISSN 0313-1971 = Annual report–National Library of Australia. 1. National Library of Australia–Periodicals. 027.594 Canberra ACT 2600 Prepared by the Executive and Public Programs Division T +61 2 6262 1111 F +61 2 6257 1703 Printed by Union Offset Hearing or speech impaired-call us via the National Relay Service on 133 677 nla.gov.au ABN 28 346 858 075 Cover image: M.H. -

SAMPLE Content Directory

SAMPLE Nearly 1,300 Journals Content Directory Participating! http://heinonline.org Please Note: This is a list of ALL content available in our two main library modules through the HeinOnline interface. Due to the various subscription packages available, access to this content may vary. TABLE OF CONTENTS: Law Journal Library ..................................................................................................................................... pp. 1-25 Legal Classics Library................................................................................................................................. pp. 26-56 LAW JOURNAL LIBRARY VOLUMES YEARS Acta Juridica 1958-2003 1958-2003 Acta Universitatis Lucian Blaga 2001-2005 2001-2005 Adelaide Law Review 1-24 1960-2003 Administrative Law Journal of the American University† 1-10 1987-1996 Administrative Law Review (ABA) 1-57 1949-2005 Advocate: A Weekly Law Journal† 1-2 1888-1890 African Human Rights Law Journal 1-3 2001-2003 African Journal of Legal Studies 1 2004-2005 Air Force Law Review 1-58 1959-2006 Air Law Review † 1-12 1930-1941 Akron Law Review 1-38 1967-2005 Akron Tax Journal 1-21 1983-2006 Alabama Law Journal (Birmingham) † 1-5 1925-1930 Alabama Law Journal (Montgomery) † 1-4 1882-1885 Alabama Law Review *JUST UPDATED* 1-57 1948-2006 Alaska Law Review 1-22 1984-2005 Albany Law Environmental Outlook Journal 1-10 1995-2005 Albany Law Journal † 1-70 1870-1909 Albany Law Journal of Science and Technology 1-15 1991-2005 Albany Law Review 1-69 1931-2006 Alberta Law Quarterly -

The Value of Public Service Media

The Value of Public Service Media T he worth of public service media is under increasing scrutiny in the 21st century as governments consider whether the institution is a good investment and a fair player in media markets. Mandated to provide universally accessible services and to cater for groups that are not commercially attractive, the institution often con- fronts conflicting demands. It must evidence its economic value, a concept defined by commercial logic, while delivering social value in fulfilling its largely not-for-profit public service mission and functions. Dual expectations create significant complex- The Value of ity for measuring PSM’s overall ‘public value’, a controversial policy concept that provided the theme for the RIPE@2012 conference, which took place in Sydney, Australia. This book, the sixth in the series of RIPE Readers on PSM published by NORDI- Public Service Media COM, is the culmination of robust discourse during that event and the distillation of its scholarly outcomes. Chapters are based on top tier contributions that have been revised, expanded and subject to peer review (double-blind). The collection investi- gates diverse conceptions of public service value in media, keyed to distinctions in Gregory Ferrell Lowe & Fiona Martin (eds.) the values and ideals that legitimate the public service enterprise in media in many countries. Fiona Martin (eds.) Gregory Ferrell Lowe & RIPE 2013 University of Gothenburg Box 713, SE 405 30 Göteborg, Sweden Telephone +46 31 786 00 00 (op.) Fax +46 31 786 46 55 E-mail: -

Journal Title Publisher ISSN ISSN Online Year Inception Field Of

Current at 6 December 2019 Year Field of Journal Title Publisher ISSN ISSN Online Inception Research 2019 Rating 4OR Springer Nature 1619-4500 1614-2411 2003 1503 B AACE International Transactions AACE International 1528-7106 1528-7106 1967 1503 B Abacus Wiley-Blackwell Publishing 0001-3072 1467-6281 1965 1501 A Institute of Economics, Academia Economic Papers Academia Sinica 1018-161X 1973 1402 C Academy of Accounting and Financial Academy of Accounting and 1096-3685 1997 C Studies Journal Financial Studies 1501 Academy of Management Annals Academy of Management 1941-6520 1941-6067 2008 1503 A* Academy of Management Discoveries Academy of Management 2168-1007 2015 1503 A Academy of Management Journal Academy of Management 0001-4273 1948-0989 1958 1503 A* Academy of Management Learning and Education Academy of Management 1537-260X 1944-9585 2002 1503 A* Academy of Management Perspectives Academy of Management 1558-9080 1943-4529 1987 1503 A Academy of Management Review Academy of Management 0363-7425 1930-3807 1976 1503 A* Jordan Whitney Enterprises, Academy of Marketing Studies Journal Inc 1095-6298 1095-6298 1980 1505 B Accident Analysis and Prevention Elsevier 0001-4575 1879-2057 1969 1507 A* Accountancy Business and the Public Association for Accountancy 1745-7718 2002 B Interest & Business Affairs 1501 Accounting Accountability and Performance Griffith University 1445-954X 1995 C 1501 Accounting and Business Research Taylor & Francis Online 0001-4788 2159-4260 1970 1501 A Year Field of Journal Title Publisher ISSN ISSN Online Inception -

Curriculum Vitae of the Honourable James Spigelman AC 1. Personal

Annex Curriculum Vitae of The Honourable James Spigelman AC 1. Personal Background Mr. James Spigelman is a citizen of Australia. He was born on 1 January 1946. He is married with three adult children. 2. Education Mr. Spigelman was educated at Sydney Boys High School and the University of Sydney, from which he graduated as Bachelor of Arts with First Class Honours in 1967 and Bachelor of Laws with First Class Honours and the University Medal in Law in 1971. 3. Legal Experience Mr. Spigelman was admitted as a barrister in 1976. He practised as a barrister from 1980 to 1998. He was appointed Queens Counsel in 1986. He served as acting Solicitor General of New South Wales in 1997. 4. Judicial Experience Mr. Spigelman was appointed Chief Justice of New South Wales in May 1998 and served in that office until May 2011. He sat in appeals on the full range of the Court’s civil and criminal jurisdiction. In 2003 he sat as a judge of the Supreme Court of Fiji on a constitutional case challenging the legal legitimacy of the Government of Fiji. 5. Services and Activities related to the Legal Field Mr. Spigelman was a member of the Australian Law Reform Commission from 1976 to 1979. He was the President of the Judicial Commission of New South Wales from 1998 to 2011. During those years he represented New South Wales on the Council of Chief Justices of Australia. 6. Publications Mr. Spigelman is the author of three books including Statutory Interpretation and Human Rights (2008), co-author of a fourth and of five pamphlets including National Lecture Series on Administrative Law (2004) and Are Lawyers Lemons: Competition Principles and Professional Regulation (2002). -

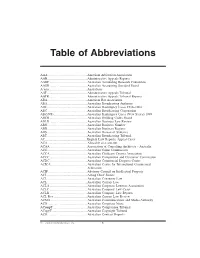

Thomson Reuters 1 Table of Abbreviations

Table of Abbreviations AAA ................................................American Arbitration Association AAR.................................................Administrative Appeals Reports AARF ..............................................Australian Accounting Research Foundation AASB ..............................................Australian Accounting Standard Board A’asia...............................................Australasia AAT .................................................Administrative Appeals Tribunal AATR...............................................Administrative Appeals Tribunal Reports ABA.................................................American Bar Association ABA.................................................Australian Broadcasting Authority ABC.................................................Australian Bankruptcy Cases 1928–1964 ABC.................................................Australian Broadcasting Corporation ABC(NS) .........................................Australian Bankruptcy Cases (New Series) 1999– ABCB ..............................................Australian Building Codes Board ABLR ..............................................Australian Business Law Review ABN.................................................Australian Business Number ABR.................................................Australian Business Register ABS .................................................Australian Bureau of Statistics ABT .................................................Australian Broadcasting Tribunal AC....................................................English -

The Honourable James Spigelman AC QC Served As Chief Justice of New South Wales, Australia’S Largest State, from 1998 Until the End May 2011

JAMES SPIGELMAN AC QC The Honourable James Spigelman AC QC served as Chief Justice of New South Wales, Australia’s largest state, from 1998 until the end May 2011. In July, 2013 he was appointed a Non-Permanent Judge of the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal. After his retirement as Chief Justice he joined One Essex Court, The Temple, London as an arbitrator. He has since been appointed Chair of panels with seats in London (x6), Singapore (x5), Dubai, Sydney (x2), Perth and ICSID, as an umpire in Singapore, as sole arbitrator in one case in Singapore and one case in Melbourne, and in two, related, disputes in Sydney, to determine a privilege issue in a NAFTA arbitration and as mediator in an Australian/UK dispute. He has also been a party appointed arbitrator on five panels in London, six panels in Singapore and panels in Sydney, Melbourne, Kuala Lumpur, Frankfurt, the Court of Arbiration for Sport and in four ICSID and two UNCITRAL investment treaty cases. From 1972 James Spigelman was Senior Advisor and Principal Private Secretary to the Prime Minister of Australia, before appointment as Permanent Secretary of the Department of Media in 1975. He was a member of the Australian Law Reform Commission from 1976 to 1979. He commenced practice at the NSW Bar in 1980. He was appointed Queen’s Counsel in 1986. He was acting Solicitor General of New South Wales in 1997. He has served on the boards of a number of cultural and educational institutions, including as Chair of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, the National Libray of Australia, the Australian Film Finance Corporation and the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney. -

Saving the Nation's Memory Bank an Open Letter to the Prime Minister

Saving the Nation’s Memory Bank An Open Letter to the Prime Minister We write as friends and supporters of the National Archives of Australia. Some of us are historians, including multiple winners of Prime Minister’s Awards, some are independent writers and researchers, and some are former members of the National Archives Advisory Council. We have differing political viewpoints but share a deep love for the knowledge of Australia’s past embodied in its archives and libraries. We are writing to you because we fear that the integrity of the nation’s premier memory bank, the National Archives of Australia, is in jeopardy and to urge you to secure its future. As the institution created by parliament to maintain the official records of the Commonwealth, the National Archives is one of the pillars of our democracy. It makes decision-making more transparent. It holds governments, past and present, to account. And in the words of Justice Michael Kirby, it ‘holds up a mirror to the people of Australia’. In this respect, the National Archives is not like other cultural institutions, such as museums, galleries and opera houses. Its most important users have yet to be born. The value of many items in its collection may not become apparent for many years because we simply do not know what questions future inquirers may ask. Only in recent years, for example, have researchers begun to tap the riches of the National Archives’ repatriation records, the largest continuous record of the health of any people anywhere, for medical as well as historical research. -

A Half-Closed Book

A HALF-CLOSED BOOK Compiled by J. L. Herrera TO THE MEMORY OF: Mary Brice AND WITH SPECIAL THANKS TO: Madge Portwin, Margaret Clarke, Isla MacGregor, Bob Clark, Betty Cameron, Ken Herrera, Cheryl Perriman, and sundry libraries, op-shops, and book exchanges INTRODUCTION Just one more ramble through unexpected byways and surprising twists and turns … yes, I think everyone is allowed to go out with neither bang nor whimper but with her eyes glued to the page … Poor dear, people can say, she didn’t see that bus coming … The difficulty of course is where to store everything; and finding room in my mind is sometimes as tricky as finding room in my bedroom. But was it a good idea to do a short writer’s calendar? A year instead of my usual three years. I had mixed feelings about it. It was nice to see a book take shape so (relatively) swiftly. But I also felt the bits and pieces hadn’t had time to marinate fully. That sense of organic development had been hurried. I also found I tended to run with the simpler stories rather than the ones that needed some research—and some luck, some serendipity. On the other hand, how long a soaking constitutes a decent marinade? Not being a good cook I always find that hard to decide … So this will be a book without a deadline. One which can just wander along in spare moments. Its date will have to wait. Even so, I hope that anyone who happens to read it some day will enjoy it as much as I always enjoy the compiling of books on writing and reading. -

LDS List of Publications

LIONEL D. SMITH List of Publications 3 February 2016 q Books Waters’ Law of Trusts in Canada, 4th edition; with Donovan Waters and Mark Gillen (Toronto: Thomson/Carswell, 2012). As in the 3rd edition (2005), I was responsible for chapters 10-11, 17-21, 23-30, and the appendices. Canadian Corporate Law: Cases, Notes and Materials, 4th edition; with Bruce Welling and Leonard Rotman (Toronto: LexisNexis Canada, 2010). In this edition, I was responsible for Chapters 5, 6, and 7. I also participated, with different responsibilities and co-authors, in the first (1996), second (2001) and third (2006) editions. Oosterhoff on Trusts: Text, Commentary and Materials, 7th edition; with Albert Oosterhoff, Robert Chambers, and Mitchell McInnes (Toronto: Thomson/Carswell, 2009). In this edition, I was responsible for Chapters 1, 10 and 15. I also participated, with different responsibilities, in the 6th edition (2004). Commercial Trusts in European Private Law; with Michele Graziadei and Ugo Mattei (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005; paperback edition, 2009). The three co-authors wrote together sections 1 and 2 in Part I, and Part III, and edited the book, to which there were 22 other contributors. I am the sole author of the sections on English law. Reviews: (2006), 31 European Law Review 608; (2006), 20 Trust Law International 284; (2007), 11 Edinburgh Law Review 135. The Law of Restitution in Canada: Cases, Notes and Materials; with Robert Chambers, Mitchell McInnes, Jason Neyers and Stephen Pitel (Toronto: Emond Montgomery, 2004). I was responsible for Chapters 1, 2, 3, 6, 7 and 8. The Law of Tracing (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1997).