Robin Mccabe, Piano with Rachelle Mccabe, Piano

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Liner Notes (PDF)

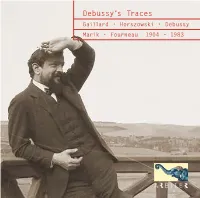

Debussy’s Traces Gaillard • Horszowski • Debussy Marik • Fourneau 1904 – 1983 Debussy’s Traces: Marius François Gaillard, CD II: Marik, Ranck, Horszowski, Garden, Debussy, Fourneau 1. Preludes, Book I: La Cathédrale engloutie 4:55 2. Preludes, Book I: Minstrels 1:57 CD I: 3. Preludes, Book II: La puerta del Vino 3:10 Marius-François Gaillard: 4. Preludes, Book II: Général Lavine 2:13 1. Valse Romantique 3:30 5. Preludes, Book II: Ondine 3:03 2. Arabesque no. 1 3:00 6. Preludes, Book II Homage à S. Pickwick, Esq. 2:39 3. Arabesque no. 2 2:34 7. Estampes: Pagodes 3:56 4. Ballade 5:20 8. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 4:49 5. Mazurka 2:52 Irén Marik: 6. Suite Bergamasque: Prélude 3:31 9. Preludes, Book I: Des pas sur la neige 3:10 7. Suite Bergamasque: Menuet 4:53 10. Preludes, Book II: Les fées sont d’exquises danseuses 8. Suite Bergamasque: Clair de lune 4:07 3:03 9. Pour le Piano: Prélude 3:47 Mieczysław Horszowski: Childrens Corner Suite: 10. Pour le Piano: Sarabande 5:08 11. Doctor Gradus ad Parnassum 2:48 11. Pour le Piano: Toccata 3:53 12. Jimbo’s lullaby 3:16 12. Masques 5:15 13 Serenade of the Doll 2:52 13. Estampes: Pagodes 3:49 14. The snow is dancing 3:01 14. Estampes: La soirée dans Grenade 3:53 15. The little Shepherd 2:16 15. Estampes: Jardins sous la pluie 3:27 16. Golliwog’s Cake walk 3:07 16. Images, Book I: Reflets dans l’eau 4:01 Mary Garden & Claude Debussy: Ariettes oubliées: 17. -

A Study of Ravel's Le Tombeau De Couperin

SYNTHESIS OF TRADITION AND INNOVATION: A STUDY OF RAVEL’S LE TOMBEAU DE COUPERIN BY CHIH-YI CHEN Submitted to the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Doctor of Music Indiana University MAY, 2013 Accepted by the faculty of the Jacobs School of Music, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Music ______________________________________________ Luba-Edlina Dubinsky, Research Director and Chair ____________________________________________ Jean-Louis Haguenauer ____________________________________________ Karen Shaw ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my tremendous gratitude to several individuals without whose support I would not have been able to complete this essay and conclude my long pursuit of the Doctor of Music degree. Firstly, I would like to thank my committee chair, Professor Luba Edlina-Dubinsky, for her musical inspirations, artistry, and devotion in teaching. Her passion for music and her belief in me are what motivated me to begin this journey. I would like to thank my committee members, Professor Jean-Louis Haguenauer and Dr. Karen Shaw, for their continuous supervision and never-ending encouragement that helped me along the way. I also would like to thank Professor Evelyne Brancart, who was on my committee in the earlier part of my study, for her unceasing support and wisdom. I have learned so much from each one of you. Additionally, I would like to thank Professor Mimi Zweig and the entire Indiana University String Academy, for their unconditional friendship and love. They have become my family and home away from home, and without them I would not have been where I am today. -

FRENCH SYMPHONIES from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

FRENCH SYMPHONIES From the Nineteenth Century To The Present A Discography Of CDs And LPs Prepared by Michael Herman NICOLAS BACRI (b. 1961) Born in Paris. He began piano lessons at the age of seven and continued with the study of harmony, counterpoint, analysis and composition as a teenager with Françoise Gangloff-Levéchin, Christian Manen and Louis Saguer. He then entered the Paris Conservatory where he studied with a number of composers including Claude Ballif, Marius Constant, Serge Nigg, and Michel Philippot. He attended the French Academy in Rome and after returning to Paris, he worked as head of chamber music for Radio France. He has since concentrated on composing. He has composed orchestral, chamber, instrumental, vocal and choral works. His unrecorded Symphonies are: Nos. 1, Op. 11 (1983-4), 2, Op. 22 (1986-8), 3, Op. 33 "Sinfonia da Requiem" (1988-94) and 5 , Op. 55 "Concerto for Orchestra" (1996-7).There is also a Sinfonietta for String Orchestra, Op. 72 (2001) and a Sinfonia Concertante for Orchestra, Op. 83a (1995-96/rév.2006) . Symphony No. 4, Op. 49 "Symphonie Classique - Sturm und Drang" (1995-6) Jean-Jacques Kantorow/Tapiola Sinfonietta ( + Flute Concerto, Concerto Amoroso, Concerto Nostalgico and Nocturne for Cello and Strings) BIS CD-1579 (2009) Symphony No. 6, Op. 60 (1998) Leonard Slatkin/Orchestre National de France ( + Henderson: Einstein's Violin, El Khoury: Les Fleuves Engloutis, Maskats: Tango, Plate: You Must Finish Your Journey Alone, and Theofanidis: Rainbow Body) GRAMOPHONE MASTE (2003) (issued by Gramophone Magazine) CLAUDE BALLIF (1924-2004) Born in Paris. His musical training began at the Bordeaux Conservatory but he went on to the Paris Conservatory where he was taught by Tony Aubin, Noël Gallon and Olivier Messiaen. -

Nietzsche, Debussy, and the Shadow of Wagner

NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Tekla B. Babyak May 2014 ©2014 Tekla B. Babyak ii ABSTRACT NIETZSCHE, DEBUSSY, AND THE SHADOW OF WAGNER Tekla B. Babyak, Ph.D. Cornell University 2014 Debussy was an ardent nationalist who sought to purge all German (especially Wagnerian) stylistic features from his music. He claimed that he wanted his music to express his French identity. Much of his music, however, is saturated with markers of exoticism. My dissertation explores the relationship between his interest in musical exoticism and his anti-Wagnerian nationalism. I argue that he used exotic markers as a nationalistic reaction against Wagner. He perceived these markers as symbols of French identity. By the time that he started writing exotic music, in the 1890’s, exoticism was a deeply entrenched tradition in French musical culture. Many 19th-century French composers, including Felicien David, Bizet, Massenet, and Saint-Saëns, founded this tradition of musical exoticism and established a lexicon of exotic markers, such as modality, static harmonies, descending chromatic lines and pentatonicism. Through incorporating these markers into his musical style, Debussy gives his music a French nationalistic stamp. I argue that the German philosopher Nietzsche shaped Debussy’s nationalistic attitude toward musical exoticism. In 1888, Nietzsche asserted that Bizet’s musical exoticism was an effective antidote to Wagner. Nietzsche wrote that music should be “Mediterranized,” a dictum that became extremely famous in fin-de-siècle France. -

Solo List and Reccomended List for 02-03-04 Ver 3

Please read this before using this recommended guide! The following pages are being uploaded to the OSSAA webpage STRICTLY AS A GUIDE TO SOLO AND ENSEMBLE LITERATURE. In 1999 there was a desire to have a required list of solo and ensemble literature, similar to the PML that large groups are required to perform. Many hours were spent creating the following document to provide “graded lists” of literature for every instrument and voice part. The theory was a student who made a superior rating on a solo would be required to move up the list the next year, to a more challenging solo. After 2 years of debating the issue, the music advisory committee voted NOT to continue with the solo/ensemble required list because there was simply too much music written to confine a person to perform from such a limited list. In 2001 the music advisor committee voted NOT to proceed with the required list, but rather use it as “Recommended Literature” for each instrument or voice part. Any reference to “required lists” or “no exceptions” in this document need to be ignored, as it has not been updated since 2001. If you have any questions as to the rules and regulations governing solo and ensemble events, please refer back to the OSSAA Rules and Regulation Manual for the current year, or contact the music administrator at the OSSAA. 105 SOLO ENSEMBLE REGULATIONS 1. Pianos - It is recommended that you use digital pianos when accoustic pianos are not available or if it is most cost effective to use a digital piano. -

Toscanini VII, 1937-1942

Toscanini VII, 1937-1942: NBC, London, Netherlands, Lucerne, Buenos Aires, Philadelphia We now return to our regularly scheduled program, and with it will come my first detailed analyses of Toscanini’s style in various music because, for once, we have a number of complete performances by alternate orchestras to compare. This is paramount because it shows quite clear- ly that, although he had a uniform approach to music and insisted on both technical perfection and emotional commitment from his orchestras, he did not, as Stokowski or Furtwängler did, impose a specific sound on his orchestras. Although he insisted on uniform bowing in the case of the Philadelphia Orchestra, for instance, one can still discern the classic Philadelphia Orchestra sound, despite its being “neatened up” to meet his standards. In the case of the BBC Symphony, for instance, the sound he elicited from them was not far removed from the sound that Adrian Boult got out of them, in part because Boult himself preferred a lean, clean sound as did Tosca- nini. We shall also see that, for better or worse, the various guest conductors of the NBC Sym- phony Orchestra did not get vastly improved sound result out of them, not even that wizard of orchestral sound, Leopold Stokowki, because the sound profile of the orchestra was neither warm in timbre nor fluid in phrasing. Toscanini’s agreement to come back to New York to head an orchestra created (pretty much) for him is still shrouded in mystery. All we know for certain is that Samuel Chotzinoff, representing David Sarnoff and RCA, went to see him in Italy and made him the offer, and that he first turned it down. -

Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes Vivian Buchanan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected]

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 6-4-2018 Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes Vivian Buchanan Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Buchanan, Vivian, "Evolving Performance Practice of Debussy's Piano Preludes" (2018). LSU Master's Theses. 4744. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/4744 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EVOLVING PERFORMANCE PRACTICE OF DEBUSSY’S PIANO PRELUDES A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music in The Department of Music and Dramatic Arts by Vivian Buchanan B.M., New England Conservatory of Music, 2016 August 2018 Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………..iii Chapter 1. Introduction………………………………………………………………… 1 2. The Welte-Mignon…………………………………………………………. 7 3. The French Harpsichord Tradition………………………………………….18 4. Debussy’s Piano Rolls……………………………………………………....35 5. The Early Debussystes……………………………………………………...52 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………...63 Selected Discography………………………………………………………………..66 Vita…………………………………………………………………………………..67 ii Abstract Between 1910 and 1912 Claude Debussy recorded twelve of his solo piano works for the player piano company Welte-Mignon. Although Debussy frequently instructed his students to play his music exactly as written, his own recordings are rife with artistic liberties and interpretive freedom. -

L'isle Joyeuse

Composing with Prototypes: Charting Debussy's L'Isle joyeuse Matthew Brown Imagine two scenarios. The first (SI) involves a short, rather crusty, middle-aged composer. A neighbor has just knocked on his door. The composer sits at his piano and plays a short motive - three eighth-note Gs followed by a half-note Ek He decides to add a fifth note. He tries an At, but it doesn't sound right. Next, he tries a Bt; that note doesn't work either. After testing every possibility, he finally picks F. Over the next few months, the short, rather crusty middle-aged composer uses this same strategy to write an entire symphony. The second scenario (S2) is quite different. A small, rather charismatic, young composer is at his desk. He has just returned from an after-dinner walk and is so inspired by the sound of the wind in the trees that he decides to write a new piece. He sits quietly in his chair until the whole thing takes shape in his mind. He then copies out the complete score from memory in one sitting. The small, rather charismatic, young composer eventually goes to bed; the next morning, he sends it off to his publisher without a single alteration. Although both scenarios are utterly implausible - they are straw men constructed for argument's sake - it is not hard to put names to them. SI captures the popular image of Beethoven. From eyewitness reports as well as from the composer's own letters and musical manuscripts, Beethoven is often remembered for the way in which he labored over his scores, meticulously reworking them over many years. -

'L'isle Joyeuse'

Climax as Orgasm: On Debussy’s ‘L’isle Joyeuse’ Esteban Buch To cite this version: Esteban Buch. Climax as Orgasm: On Debussy’s ‘L’isle Joyeuse’. Music and Letters, Oxford Univer- sity Press (OUP), 2019, 100 (1), pp.24-60. 10.1093/ml/gcz001. hal-02954014 HAL Id: hal-02954014 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02954014 Submitted on 30 Sep 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Esteban Buch, ‘Climax as Orgasm: On Debussy’s “L’isle Joyeuse”’, Music and Letters 100/1 (February 2019), p. 24-60. Climax as Orgasm: On Debussy’s L’isle joyeuse This article discusses the relationship of musical climax and orgasm by considering the case of L’isle joyeuse, a piano piece that Claude Debussy (1862-1918) began in 1903, completing it in the Summer of 1904 soon after starting a sentimental relationship with Emma Bardac, née Moyse (1862-1934), his second wife and the mother of his daughter Claude-Emma, alias ‘Chouchou’ (1905-1919). By exploring the genesis of the piece, I suggest that the creative process started as the pursuit of a solitary exotic male fantasy, culminating in Debussy’s sexual encounter with Emma and leading the composer to inscribe their shared experience in the final, revised form of the piece. -

ABSTRACT the Influence of Poetry on the Piano Music of Early Twentieth-Century France and England Meredith K. Rigby, M.M. Mentor

ABSTRACT The Influence of Poetry on the Piano Music of Early Twentieth-Century France and England Meredith K. Rigby, M.M. Mentor: Laurel E. Zeiss, Ph.D. The turn of the century in France saw an increased intensity of interest in equating the arts of poetry and music. England experienced a similar trend. Debussy and Ravel were influenced by the Symbolist poets and their aesthetic of abstract musical expression of ideas and outright rejection of Romanticism. John Ireland in England sought to express the sense of loss and longing in Victorian poetry through his music, while Joseph Holbrooke based his musical forms on direct representation of dramatic and mysterious Romantic poetry, especially that of Edgar Allan Poe, through text painting and similar techniques. Each of these composers’ music reflects formal aspects, emotional values, and rhythmic qualities of the poetry in which they were immersed, as analyses of Debussy’s Preludes, Ravel’s Jeux d’eau, Ireland’s Green Ways, and Holbrooke’s Nocturnes demonstrate. The Influence of Poetry on the Piano Music of Early Twentieth-Century France and England by Meredith K. Rigby, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the School of Music Gary C. Mortenson, D.M.A., Dean Laurel E. Zeiss, Ph.D., Graduate Program Director Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Music Approved by the Thesis Committee Laurel E. Zeiss, Ph.D., Chairperson Alfredo Colman, Ph.D. Terry Lynn Hudson, D.M.A. Accepted by the Graduate School May 2017 J. Larry Lyon, Ph.D., Dean Page bearing signatures is kept on file in the Graduate School. -

French Performance Practices in the Piano Works of Maurice Ravel

Studies in Pianistic Sonority, Nuance and Expression: French Performance Practices in the Piano Works of Maurice Ravel Iwan Llewelyn-Jones Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy School of Music Cardiff University 2016 Abstract This thesis traces the development of Maurice Ravel’s pianism in relation to sonority, nuance and expression by addressing four main areas of research that have remained largely unexplored within Ravel scholarship: the origins of Ravel’s pianism and influences to which he was exposed during his formative training; his exploration of innovative pianistic techniques with particular reference to thumb deployment; his activities as performer and teacher, and role in defining a performance tradition for his piano works; his place in the French pianistic canon. Identifying the main research questions addressed in this study, an Introduction outlines the dissertation content, explains the criteria and objectives for the performance component (Public Recital) and concludes with a literature review. Chapter 1 explores the pianistic techniques Ravel acquired during his formative training, and considers how his study of specific works from the nineteenth-century piano repertory shaped and influenced his compositional style and pianism. Chapter 2 discusses Ravel’s implementation of his idiosyncratic ‘strangler’ thumbs as articulators of melodic, harmonic, rhythmic and textural material in selected piano works. Ravel’s role in defining a performance tradition for his piano works as disseminated to succeeding generations of pianists is addressed in Chapter 3, while Chapters 4 and 5 evaluate Ravel’s impact upon twentieth-century French pianism through considering how leading French piano pedagogues and performers responded to his trailblazing piano techniques. -

G. Jean-Aubry (1882-1950)

1/15 Data G. Jean-Aubry (1882-1950) Pays : France Langue : Français Sexe : Masculin Naissance : Paris, 13-08-1882 Mort : Paris, 01-04-1950 Note : Homme de lettres. - Musicologue. - Traducteur des oeuvres de Joseph Conrad. - A toujours signé G. Jean-Aubry, mais certaines de ses publications apparaissent sous le prénom de plume Georges, celui d'un oncle proche, et qu'il a adopté en 1902. - Les prénoms Gabriel et Gérard sont des développements erronés mais figurant dans la correspondance d'André Gide à G. Jean-Aubry État-civil complet : Jean Frédéric Émile Aubry Domaines : Musique Littératures Autres formes du nom : G. Jean- Aubry (1882-1950) Gabriel Jean-Aubry (1882-1950) Georges Jean-Aubry (1882-1950) Gérard Jean-Aubry (1882-1950) G. J.-A. (1882-1950) ISNI : ISNI 0000 0001 1589 3428 (Informations sur l'ISNI) G. Jean-Aubry (1882-1950) : œuvres (287 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Œuvres textuelles (231) Valery Larbaud (1949) "Lettres à André Gide" (1948) de Valery Larbaud avec G. Jean-Aubry (1882-1950) comme Préfacier Vie de Conrad "Giro dell'oca" (1947) (1947) de Valery Larbaud avec G. Jean-Aubry (1882-1950) comme Postfacier data.bnf.fr 2/15 Data Au tombeau de Julie Le Nain vert (1946) (1946) Le centenaire de Gabriel Fauré André Gide et la musique (1945) (1945) Versailles, songes et regrets "Cambridge et la tradition anglaise, des splendeurs d'un (1944) grand passé aux promesses d'un grand avenir" (1945) de Alfred Leroy avec G. Jean-Aubry (1882-1950) comme Préfacier Paris, âges et visages La Savoie (1943) (1943) Une amitié exemplaire.