12655474 Understanding Scotland Musically

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Here Is No Doubt 2020 Has Been One of the Most Challenging Years for People on This Planet

26-28 november 2020 I S L E O F S K Y E www.seall.co.uk seall festival of small halls 2020 | Page 2 Page 3 | wwww.seall.co.uk/small-halls/tickets WE ARE the SEALL Festival of Small Halls, a premier winter festival celebrating community, culture and traditional music on Skye WE BRING big music to small halls and some of the most iconic places on the Isles of Skye and Raasay WE WON the 2019 MG Alba Scottish Traditional Music Award for best community project for our 2018 inaugural festival WE CELEBRATE our unique Island culture around Scotland’s National Day with concerts and a St Andrew’s Night Big Cèilidh WE SHOWCASE Scotland’s best traditional musicians in some of the most remote and beautiful rural locations in the UK WE DELIVER an amazing programme of concerts, workshops and sessions to communities and visitors WE ARE SEALL One of Scotland’s leading rural performing arts promoters WE LOOK FORWARD TO WELCOMING YOU seall festival of small halls 2020 | Page 4 A FEW WORDS ABOUT 2020 By engaging some of Scotland’s most remote rural On Saturday 28 November, the highly popular Small Halls Big communities in a winter celebration of the traditional music Cèilidh will take place live-streamed from the Sligachan Hotel in and heritage of the Highlands and Islands, the SEALL Festival of honour of Scotland’s national day. This year’s event is also part of Small Halls focuses on the importance of the community hall as a the philanthropic St Andrew’s Fair Saturday Festival and will raise space in which to gather and unite. -

View Or Download Full Colour Catalogue May 2021

VIEW OR DOWNLOAD FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE 1986 — 2021 CELEBRATING 35 YEARS Ian Green - Elaine Sunter Managing Director Accounts, Royalties & Promotion & Promotion. ([email protected]) ([email protected]) Orders & General Enquiries To:- Tel (0)1875 814155 email - [email protected] • Website – www.greentrax.com GREENTRAX RECORDINGS LIMITED Cockenzie Business Centre Edinburgh Road, Cockenzie, East Lothian Scotland EH32 0XL tel : 01875 814155 / fax : 01875 813545 THIS IS OUR DOWNLOAD AND VIEW FULL COLOUR CATALOGUE FOR DETAILS OF AVAILABILITY AND ON WHICH FORMATS (CD AND OR DOWNLOAD/STREAMING) SEE OUR DOWNLOAD TEXT (NUMERICAL LIST) CATALOGUE (BELOW). AWARDS AND HONOURS BESTOWED ON GREENTRAX RECORDINGS AND Dr IAN GREEN Honorary Degree of Doctorate of Music from the Royal Conservatoire, Glasgow (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – The Hamish Henderson Award for Services to Traditional Music (Ian Green) Scots Trad Awards – Hall of Fame (Ian Green) East Lothian Business Annual Achievement Award For Good Business Practises (Greentrax Recordings) Midlothian and East Lothian Chamber of Commerce – Local Business Hero Award (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Hands Up For Trad – Landmark Award (Greentrax Recordings) Featured on Scottish Television’s ‘Artery’ Series (Ian Green and Greentrax Recordings) Honorary Member of The Traditional Music and Song Association of Scotland and Haddington Pipe Band (Ian Green) ‘Fuzz to Folk – Trax of My Life’ – Biography of Ian Green Published by Luath Press. Music Type Groups : Traditional & Contemporary, Instrumental -

Download PDF 8.01 MB

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 Imagining Scotland in Music: Place, Audience, and Attraction Paul F. Moulton Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC IMAGINING SCOTLAND IN MUSIC: PLACE, AUDIENCE, AND ATTRACTION By Paul F. Moulton A Dissertation submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Dissertation of Paul F. Moulton defended on 15 September, 2008. _____________________________ Douglass Seaton Professor Directing Dissertation _____________________________ Eric C. Walker Outside Committee Member _____________________________ Denise Von Glahn Committee Member _____________________________ Michael B. Bakan Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii To Alison iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS In working on this project I have greatly benefitted from the valuable criticisms, suggestions, and encouragement of my dissertation committee. Douglass Seaton has served as an amazing advisor, spending many hours thoroughly reading and editing in a way that has shown his genuine desire to improve my skills as a scholar and to improve the final document. Denise Von Glahn, Michael Bakan, and Eric Walker have also asked pointed questions and made comments that have helped shape my thoughts and writing. Less visible in this document has been the constant support of my wife Alison. She has patiently supported me in my work that has taken us across the country. She has also been my best motivator, encouraging me to finish this work in a timely manner, and has been my devoted editor, whose sound judgement I have come to rely on. -

Diego Laverde

Diego Laverde Course: This is an invitation to explore and expand your repertoire of Latin American music, focused in the Colombian and Venezuelan harp playing. Play individual melodies, learn the main rhythmical struc- tures, supported by another instrument, “el Cuatro”, played by the tutor. Teaching will be delivered by ear but at the end of the course, he will be given written notation of the melodies as well some audio files. Biography: From Bogotá, Colombia , Diego has been playing the "Lla- nera"(low land) harp since 1982 nad has played in several Colombian and Latin American groups. This partivcular harp design is the product of the European influence and has been adopted in a beautifl area between Colombia and Venezuala called "Los Llanos (the plains). In Colombia, he taught in various music academies and was director of the Folkloric group of the Central University of Bogotá. He has toured the world as a musician with the Ballet Fol- klorico Colombiano. Since coming to the united Kingdom, he has been involved in different festivals as a perfor- mer and teacher around England, Scotland, Wales and some countries on the Continent: Edinburgh Harp Festival, Scotland (2003, 2006), Stamford Harp Festival, England (2003, 2004, 2005, 2010), Carnaval del Pueblo, England (2003 and 2004), Mosenberg and Lauterbach Harp Festivals, Germany (2005,2006,2010), Clarsach Society, London Branch Harp Weekend Sept. 2006, Spring String Weekend, Knighton North Wales March 2007, Seduced By Harps, Lommel, Belgium 2009, Royal Albert Hall and Queen Elizabeth Hall, mit seiner Band: “Ensamble Criollo”, Sup- porting Buena Vista Social Club and Salsa Celtica (2009,2010), Glastombury Festival, als Teil der Georgy Pope Band (2010). -

The Musicians______

The musicians_______________________________________________________________________ Ross Ainslie Bagpipes & Whistle Ross hails from Bridge of Earn in Perthshire. He began playing chanter at the age of 8 and like Ali Hutton studied under the watchful eye of the late great Gordon Duncan and was a member of the Vale of Atholl pipe band. Ross also plays with Salsa Celtica, Dougie Maclean's band, India Alba, Tunebook, Charlie Mckerron's trio and in a duo with Irish piper Jarlath Henderson. He released his début solo album "Wide Open" in 2013 which was voted 9th out of 50 in the Sunday Herald "The Scottish albums of 2013". He was nominated for "musician of the year" at the Radio 2 folk awards 2013 and also for "Best Instrumentalist" at the Scots Trad Music Awards in 2010 and 2012. Ali Hutton Bagpipes & Whistle Ali, from Methven in Perthshire, was inspired at the age of 7 to take up the bagpipes and came up through the ranks at the Vale of Atholl pipe band. He was taught alongside Ross Ainslie by the late, great Gordon Duncan and has gone on to become a successful multi‐instrumentalist on the Scottish music scene. He has produced and co‐produced several albums such as Treacherous Orchestra’s “Origins”, Maeve Mackinnon's “Don't sing love songs”, The Long Notes’ “In the Shadow of Stromboli” and Old Blind Dogs’ “Wherever Yet May Be”. Ali is also currently a member of Old Blind Dogs and the Ross Ainslie band but has played with Capercaillie, Deaf Shepherd, Emily Smith Band, Dougie Maclean, Back of the Moon and Brolum amongst many others. -

Music on Sundays Enjoy All 6 Concerts for the Price of 4! Six Concerts 2018-19 Email: [email protected] Or Call Carnegie Hall Box Office 01383 602302

Season Tickets only £45 Music on Sundays Enjoy all 6 concerts for the price of 4! Six Concerts 2018-19 Email: [email protected] or call Carnegie Hall Box Office 01383 602302. Single tickets £11 ((student/unemployed £1) Concerts start at 7.30pm in the Studio Annex, Carnegie Hall, East Port, Dunfermline KY12 7JA (except 13 January in main Carnegie Hall) Subsidised by Dunfermline Arts Guild email [email protected] www.daguild.co.uk Sunday 14 October 2018 Sunday 09 December 2018 Sunday 10 February 2019 Guitar Journey Pure Brass Scottish Saxophone Ensemble Pure Brass are one of UK’s most established brass Sue McKenzie, Ellie Steemson, Allon Beau- Guillermo Hill & Jonny Phillips, two of the leading quintets. Formed in 2006, they quickly built a reputa- voisin, Michael Brogan. acoustic players in Europe, take you on a musical tion for their musicianship and entertaining approach As one of Scotland’s leading contemporary journey following the development of the guitar to the concert platform. After much early success in saxophonists Sue has given UK and Scottish from its origins in Spain and North Africa along a national competitions, and through opportunities premieres of many new works for saxophone as path across Europe, Africa and the Americas. provided by their years as members of the ‘Live well as commissioning new music. Sue was the Uruguayan Hill has played and recorded with Music Now’ scheme, they have performed in venues Assistant Director of the World Saxophone Con- Mica Paris, Tom Jones, Jennifer Lopez, Brazilian such as The Wigmore Hall, St Martin in the Fields gress 2012 and is the Director of the Scottish drum master Airto Moreira and pianist Zoe and The Purcell Rooms London, as well as the Saxophone Academy. -

7X9 Studio 1 22 BIG KIC Wednesday, August 11, 2010 Kilsyth Comedy Festival August 11-13 Colzium Big Top and the Coachman Hotel

7X9 Studio 1 22 BIG KIC Wednesday, August 11, 2010 www.kilsythchronicle.co.uk Kilsyth Comedy Festival August 11-13 Colzium Big Top and The Coachman Hotel KICS have been working in Magners Glasgow International The Coachman Hotel will be Stevenson KICS Comedy event conjunction with the Scottish Comedy Festival, to create the leading venue for the Kilsyth Organizer said “we’re really very Comedy Agency, sister company Kilsyth Comedy Festival and to Comedy Festival, finishing with a excited, this is a new dimension to to The Stand Comedy Club and bring the very best in electrifying grand finale at The Big top in the festival that we would hope to the organisers behind the popular stand-up to Kilsyth this summer. Colzium Estate . Dorothy continue in future years” Wednesday, August 11 Thursday, August 12 Thursday, August 12 appearances, delivers his massively popular brand of caustic sarcasm and observational THE Kilsyth Comedy CALEDONIAN humour.We have him here on our own Festival kicks off on comedy doorstep in Wednesday 11th of August favourites Kilsyth! with an impressive VLADIMIR Appearing as our International Stand up! McTAVISH, Headline in THE show at 7.30pm at The SUSAN BIG TOP at Coachman Hotel. The line- MORRISON 7.30pm in up will include a number of AND GRAEME Colzium Estate, top comedians from around THOMAS head don’t miss this the globe who will be taking up the bill on opportunity to see time off from their hectic THE BEST OF this comic at his Fringe Festival schedule to bring their SCOTTISH night best LIVE! unique flavours of comedy to the people of at the Supporting Fred Kilsyth. -

Press Release – 3X5 – Soundhouse- Ed Fringe

The Soundhouse Organisation presents 3X5 4 chances to hear 3 of Scotland’s best 5-piece acoustic bands - Moishe’s Bagel, Kinnaris Quintet and John Goldie & the High Plains - in the extraordinary setting of The Pianodrome, Edinburgh Fringe’s newest venue. Part of Made In Scotland’s curated showcase programme Edinburgh’s The Soundhouse Organisation presents 3X5 - three of the most exciting 5-piece cross-genre acoustic bands from Scotland - Moishe’s Bagel, John Goldie & The High Plains P and Kinnaris Quintet – with three individual concerts, and one almighty showcase of all three in one show. All presented in one of the most unusual and original venues at this year’s Fringe. R The bands produce ingenious and highly listenable music, transcending categorisation, and appealing to lovers of music in all its forms. They represent what Scottish musicians excel at: melding a variety of styles, influences and origins to make exciting, world-leading sounds. E Soundhouse favourites Moishe’s Bagel play thrillingly original cutting-edge klezmer and folk music. An intoxicating, life-affirming mix of Eastern European dance music, Middle Eastern S rhythms and virtuoso performances. Their long anticipated 5th album will be launched at their gig. John Goldie is one of the best acoustic guitarists in the world right now. He is joined by his S brand new backing band, The High Plains. Playing original tunes, The High Plains is made up of some of the most accomplished string players in folk, jazz and classical music. Kinnaris Quintet is one of Scotland's hottest new folk bands. The line-up is a marriage of five exquisite musicians from diverse musical backgrounds, influences and styles, all distilled into beautifully crafted and powerful arrangements. -

Mckenzie Sawers Duo After the Tryst 1 Sally Beamish (B

After the Tryst New music for saxophone and piano mckenzie sawers duo After the Tryst 1 Sally Beamish (b. 1956) Caliban (2014) [4:16] 2 James MacMillan (b. 1959) After the Tryst (1988, arr. 1995)** [2:47] New music for saxophone and piano arr. Gerard McChrystal Judith Weir (b. 1954) Sketches from a Bagpiper’s Album (1984)** 3 1. Salute [3:31] mckenzie sawers duo 4 2. Nocturne [1:39] 5 3. Lament, over the sea [2:37] 6 Michael Nyman (b. 1944) Miserere Paraphrase (1989/94) [6:45] 7 Alasdair Nicolson (b. 1961) Slow Airs and March (1994)* [12:45] Sue McKenzie soprano saxophone (tracks 1–7, 9–12), 8 Joe Duddell (b. 1972) Fracture (1999)* [4:36] alto saxophone (track 8) 9 Ian Wilson (b. 1964) Drive (1992)* [6:13] Ingrid Sawers piano 10 Cecilia McDowall (b. 1951) Mein blaues Klavier (2006)* [10:56] 11 Michael Nyman Shaping the Curve (1990) [8:39] 12 Graham Fitkin (b. 1963) Bob (1996)** [2:14] Total playing time [67:06] * premiere recording ** first recording of this version Sue McKenzie would like to thank Kerry Long at Recorded on 11-13 July 2017 Cover image: Sorrow is Kissing Me, Join the Delphian mailing list: Yanagisawa Saxophones, Tom Bacon and Jean- at Broughton St Mary’s Parish Berlin, Germany, 2010; black and white www.delphianrecords.co.uk/join Church, Edinburgh photograph © Ronny Behnert / François Bescond at D’Addario Woodwinds, Ruth Like us on Facebook: Producer/Engineer: Paul Baxter Bridgeman Images www.facebook.com/delphianrecords Prowse and Malcolm Kirkpatrick at The Wind 24-bit digital editing: Matthew Swan Artist photography © Marc Marnie Section, Judith Walsh, Mike Brogan, all the Philps 24-bit digital mastering: Paul Baxter Design: John Christ Follow us on Twitter: and especially Mackinnon and Emily Green. -

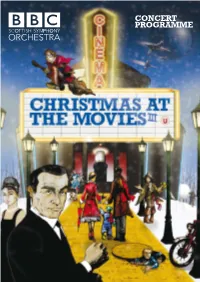

Concert Programme

CONCERT PROGRAMME CHRISTMAS at THE MOVIES Jamie MacDougall has established His discography includes critically acclaimed and Edinburgh International Festival, and it himself as one of the country’s most versatile CDs on the ASV, Naxos and Dutton labels, plays in venues all over Scotland. Abroad, it City Halls, Glasgow singers and performers. Since 2001 he has including two with the Royal Philharmonic has appeared in many of the great musical Sunday, 20 December 2009, 3.00pm been the voice of classical music on BBC Orchestra and, most recently, three world centres of Europe and has toured the USA, Radio Scotland and he has also moved into premiere recordings with Roger Chase and South America and been twice to China, television, annually presenting BBC Proms in the BBC Concert Orchestra. Since 2005 he most recently in May 2008. The majority of its Leader: Elizabeth Layton the Park Glasgow as part of the BBC’s Last has conducted the BBC Philharmonic for the performances are broadcast on BBC Radio Presented by: Jamie MacDougall Night of the Proms. He continues to tour annual BBC Proms in the Park Manchester, 3, and its innovative concert programmes Conducted by: Stephen Bell with Caledon – Scotland’s Tenors (of which and in 2008 made his BBC Proms debut and acclaimed recordings have made it the he is a founding member) and returned at the Royal Albert Hall with the highly recipient of numerous awards, including to Berlin with their new show ‘Whirlin in successful Doctor Who Prom. This season four Gramophone Awards. Edinburgh-born Berlin’, which was subsequently released on sees engagements with a number of Donald Runnicles became the BBC SSO’s PLEASE ENSURE ALL MOBILE TELEPHONES This afternoon’s concert will be broadcast on BBC Radio Scotland DVD and CD last month. -

Écosse Bro-Skos Scotland

ÉCOSSE BRO-SKOS SCOTLAND Showcasing Scotland at Festival Interceltique de Lorient ALBA The Pavilion of Honour Thank you to all our generous sponsors for their kind support at this year’s Festival Interceltique de Lorient. Partners – 2 CONTENTS WELCOME | FÀILTE 4 SHOWCASING SCOTLAND AT FESTIVAL 7 INTERCELTIQUE DE LORIENT DON’T MISS 18 SCOTLAND PAVILION PROGRAMME 25 COMPETITION 29 PARTNERS 31 – 3 WELCOME | FÀILTE | BIENVENUE | DEGEMER MAT Welcome to Scotland in Lorient! We are delighted to be the Country of Honour at this year’s Festival Interceltique de Lorient. Scotland’s folk, traditional and Gaelic music scenes have arguably never been stronger, and we are delighted to present a packed ten-day programme – across the festival, and in the Scotland Pavilion – featuring legendary, renowned artists alongside some of the most groundbreaking talent taking our music in exciting new directions. It’s often said that a country’s music is shaped by its landscape, and so we urge you to discover more about just that, and stop by the VisitScotland and HebCelt stands to explore the huge array of destinations, festivals and vacation possibilities that Scotland has to offer. Scotland is a country also renowned for its food and drink, and we’re pleased to be able to offer a selection of our finest produce at the festival as well. As with visiting Scotland itself, we promise everyone a very warm welcome, and look forward to seeing you over the festival at the Scotland Pavilion. Slàinte! Merci! Yec’head mat! #LorientFestival17 festival-interceltique.bzh/le-pays-invite – 4 ‘Over 200 of Scotland’s finest musicians are performing at this year’s festival – representing emerging young talent and firmly established acts – and are sure to delight existing fans and create new ones. -

Klezmer and World Folk from Scotland and Beyond

Moishe’s Bagel “true originals” The Guardian Klezmer and world folk from Scotland and beyond This brilliantly accomplished and fearless five-piece emphatically puts the “class” into “unclassifiable” Scotsman Royal Conservatoire of Scotland Associate Artists 2019-2020 Hippodrome Festival of Silent Film commissioned artists 2015 Sunday Times top 10 world albums Songlines Top of the World artists 2020 Australian tour New album out in 2020 Thrillingly original cutting-edge klezmer and world music. An intoxicating, life-affirming mix of Eastern European dance music, Middle Eastern rhythms and virtuoso performances. Boasting some of Scotland’s best instrumentalists (Grit Orchestra, Salsa Celtica, Scottish National Formed in Edinburgh in 2003, Jazz Orchestra), the band will draw you in, turn Moishe’s Bagel combines the energy and you inside out, and leave you smiling passion of world folk with the excitement uncontrollably – all in the space of one tune. and soul of improvisation. exhilarating, full-flavoured stuff, often breath-takingly intricate but played with jubilation and the momentum of an express train The Herald Performances include: London Jazz Café Dublin Royal Concert Hall,"Edinburgh Queens Hall,"Cardiff St David’s Hall LINKS Sage Gateshead,"St George’s Bristol,"Famous Spiegeltent youtube here Celtic Connections,"BBC Biggest Weekend,"Edinburgh Jazz and Blues Festival soundcloud here Knockengorroch Festival,"Larmer Tree Festival National Folk Festival, Canberra,"Fairbridge Festival, Perth facebook here Folk Holidays, Czech Republic,"Krakow Crossroads Festival photos here Plus sessions for BBC Radio 6, Radio 3, Radio Scotland, RTE… moishesbagel.com.