SPRING 1979 61 Here and There: Some Peruvian and Some Colombian Theatre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Air France's A380 Is Coming to Mexico!

Air France’s A380 is coming to Mexico! February 2016 © Stéphan Gladieu Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral This winter, Air France is offering six weekly frequencies between Paris-Charles de Gaulle and Mexico. Since 12 January 2016, there have been three weekly flights operated by Airbus A380, the Company’s largest super jumbo (Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday). The three other flights are operated by Boeing 777-300. From 28 March 2016, the A380 will fly between the two cities daily. On board, customers will have the option of travelling in four flight cabins ensuring optimum comfort – La Première, Business, Premium Economy and Economy. Airbus A380 Flight Schedule (in local time) throughout the winter 2016 season • AF 438: leaves Paris-Charles de Gaulle at 13:30, arrives in Mexico at 18:40; • AF 439: leaves Mexico at 21:10, arrives at Paris- Charles de Gaulle at 14:25. Flights operated by A380 on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays from 12 January to 26 March 2016. Daily flights by A380 as from 27 March 2016. © Stéphan Gladieu The comfort of an A380 Boarding an Air France Airbus A380 always guarantees an exceptional trip. On board, the 516 passengers travel in perfect comfort in exceptionally spacious cabins. Two hundred and twenty windows fill the aircraft with natural light, and changing background lighting allows passengers to cross time zones fatigue-free. In addition, six bars are located throughout the aircraft, giving passengers the chance to meet up during the flight. With cabin noise levels five decibels lower than industry standards, the A380 is a particularly quiet aircraft and features the latest entertainment and comfort technology. -

Foreign Branches of American National Banks, Dec

1950 114 REPORT OF THE COMPTROLLER OF THE CURRENCY TABLE NO. 21. ForeigrTbranches^of Americanjnational^bankSy Dec. 30, 1950 BANK OF AMERICA NATIONAL TRUST AND SAVINGS NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK, N. Y.—Con- ASSOCIATION, SAN FRANCISCO, CALIF.: Brazil: China: Recife (Pernambuco). Shanghai. Porto Alegre. Rio de Janeiro. England: Salvador. Santos. London. Sao Paulo. Guam: Canal Zone: Agana. Balboa. Japan: Cristobal. Kobe. Chile: Tokyo. Santiago. Yokohama. Valparaiso. Philippines: Colombia: Manila. Barranquilla. Thailand: Bogota. Medellin. Bangkok. Cuba: FIRST NATIONAL BANK OF BOSTON, MASS.: Caibarien. Argentina: Cardenas. Avellaneda. Havana. Buenos Aires. Havana (Cuatro Caminos). Buenos Aires (Alsina). Havana (Galiano). Buenos Aires (Constitution). Havana (La Lonja). Buenos Aires (Once). Manzanillo. Matanzas. Rosario. Santiago de Cuba. Brazil: Rio de Janeiro. England: Santos. London. Sao Paulo. London (West End). Cuba: Hong Kong: Cienfuegos. Hong Kong. Havana. Havana (Avenida de Italia). India: Havana (Avenida Maximo Gomez). Sancti Spiritus. Bombay. Santiago de Cuba. Calcutta. Japan: Osaka. CHASE NATIONAL BANK OF NEW YORK, N. Y.: Tokyo. Canal Zone: Yokohama. Balboa. Cristobal. Mexico: Mexico City. Cuba: Mexico City (La Catolica). Havana. Panama: England: Panama'City. London (Berkeley Square). London (Bush House, Aldwych). Peru: London (Lombard). Lima. Germany: Philippines: Frankfurt am Main. Heidelberg. Cebu. Clark Field. Stuttgart. Manila. Japan: Manila (Port Area Branch). Osaka. Tokyo. Puerto Rico: Arecibo. Panama: Bayamon. Colon. Caguas. David. Mayaguez. Panama City. Ponce. Puerto Rico: San Juan. San Juan. Singapore: Singapore. NATIONAL CITY BANK OF NEW YORK, N. Y.: Argentina: Uruguay: Buenos Aires. Montevideo. Buenos Aires (Flores). Buenos Aires (Plaza Once). Venezuela: Rosario. Caracas. NOTE.—Consolidated statement of the assets and liabilities of the above-named branches as of Dec. -

Do Bus Rapid Transit Systems Improve Accessibility to Job Opportunities for the Poor? the Case of Lima, Peru

sustainability Article Do Bus Rapid Transit Systems Improve Accessibility to Job Opportunities for the Poor? The Case of Lima, Peru Daniel Oviedo 1,*, Lynn Scholl 2,*, Marco Innao 3 and Lauramaria Pedraza 2 1 Lecturer Development Planning Unit, University College London, London WC1H 9EZ, UK 2 Inter-American Development Bank, Washington, DC 20577, USA; [email protected] 3 Louis Berger, 96 Morton St, New York, NY 10014, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (D.O.); [email protected] (L.S.); Tel.: +44-7428-236791 (D.O.); +1-202-623-2224 (L.S.) Received: 12 March 2019; Accepted: 10 May 2019; Published: 16 May 2019 Abstract: Investments in public transit infrastructure in Latin America and the Caribbean often aim to reduce spatial and social inequalities by improving accessibility to jobs and other opportunities for vulnerable populations. One of the central goals of Lima’s Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) project was to connect low-income populations living in the peripheries to jobs in the city center, a policy objective that has not yet been evaluated. Building on secondary datasets of employment, household socio-demographics and origin–destination surveys before and after the BRT began operations, this paper examines the contribution of Lima’s BRT system to accessibility to employment in the city, particularly for low-income public transit users. We estimated the effects on potential accessibility to employment, comparing impacts on lower versus higher income populations, and assessed the changes in location-based accessibility to employment before (2004) and after implementation (2012) for treatment and comparison groups. -

El Tango Y La Cultura Popular En La Reciente Narrativa Argentina

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2018 El tango y la cultura popular en la reciente narrativa argentina Monica A. Agrest The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2680 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EL TANGO Y LA CULTURA POPULAR EN LA RECIENTE NARRATIVA ARGENTINA by Mónica Adriana Agrest A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 MÓNICA ADRIANA AGREST All Rights Reserved ii EL TANGO Y LA CULTURA POPULAR EN LA RECIENTE NARRATIVA ARGENTINA by Mónica Adriana Agrest This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Latin American, Iberian and Latino Cultures in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ ________________________________________ November 16th, 2017 Malva E. Filer Chair of Examining Committee ________________________________________ ________________________________________ November 16th, 2017 Fernando DeGiovanni Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Silvia Dapía Nora Glickman Margaret E. Crahan THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT EL TANGO Y LA CULTURA POPULAR EN LA RECIENTE NARRATIVA ARGENTINA by Mónica Adriana Agrest Advisor: Malva E. Filer The aim of this doctoral thesis is to show that Tango as scenario, background, atmosphere or lending its stanzas and language, helps determine the tone and even the sentiment of disappointment and nostalgia, which are in much of Argentine recent narrative. -

PROYECTO DE DECLARACION El Senado De La Nación DECLARA Su Profundo Pesar Por El Fallecimiento De La Señora Amelia

“2016 Año del Bicentenario de la Declaración de la Independencia Nacional” Senado de la Nación Secretaria Parlamentaria Dirección General de Publicaciones (S-796/16) PROYECTO DE DECLARACION El Senado de la Nación DECLARA Su profundo pesar por el fallecimiento de la señora Amelia Bence, nacida con el nombre de María Amelia Batvinik el día 13 de noviembre de 1914. Actriz de prestigiosa trayectoria artística, calificada como una de los más grandes referentes de la escena nacional cuyo trabajo también ha trascendido las fronteras del país, representándolo sin descanso en el cine, el teatro y la televisión. Liliana T. Negre de Alonso. – FUNDAMENTOS Señor Presidente: Creemos que es necesario declarar nuestro profundo pesar por el fallecimiento de la señora Amelia Bence, nacida con el nombre de María Amelia Batvinik el día 13 de noviembre de 1914. Actriz de prestigiosa trayectoria artística, calificada como una de los más grandes referentes de la escena nacional cuyo trabajo también ha trascendido las fronteras del país, representándolo sin descanso en el cine, el teatro y la televisión. La menor de siete hermanos, se llamaba en realidad María Amelia Batvinik. Creció en una casa con dos patios, en Paraguay y Riobamba, mientras que sus padres, lituanos, resolvían si era decente darle permiso para estudiar teatro en el Instituto Labardén que funcionaba en el Teatro Colón, donde finalmente cursó junto con la gigante poetaAlfonsina Storni. El debut en pantalla llegó en 1933, con "Dancing", de Luis MogliaBarth. Más tarde otras cintas, hasta que "La guerra gaucha" (Lucas Demare, 1942) la empujó a roles protagónicos. "Los ojos más lindos del mundo" (Luis Saslavsky, 1943), este último es quienle impuso el mote de los ojos más lindos del mundo. -

Artistic Swimming

ARTISTIC SWIMMING EVENTS Women (3) Duets Teams Highlight Mixed (1) Duets QUOTA Qualification Host NOC Total Men 7 1 8 Women 64 8 72 Total 71 9 80 athletes MAXIMUM QUOTA PER NOC EVENT Qualification Host NOC Total Duets 1 duet (2 athletes) 1 duet (2 athletes) 12 duets of 2 athletes Teams 1 team (8 athletes) 1 team (8 athletes) 8 teams of 8 athletes Highlight 1 team (8 athletes) 1 team (8 athletes) 8 teams of 8 athletes Mixed Duets 1 duet (2 athletes) 1 duet (2 athletes) 8 Duets of 2 athletes Total 9 athletes (8 women + 1 man) 9 athletes (8 women + 1 man) 80 athletes (72 women + 8 men) Athletes may register for more than one event. Eight teams with a maximum of 8 (eight) athletes each may participate in the team and highlight competition (no reserves will be allowed). Eight duets with a maximum of 2(two) athletes (one man and one woman) each may participate in the mixed duet competition (no reserves will be allowed). Twelve teams with a maximum of 24 athletes (no reserves will be allowed) may participate in the duet competition. As Host Country, Colombia automatically will qualify one team in each event, with a maximum of 9 athletes (8 women and 1 man). Athlete eligibility The athletes must have signed and submitted the Athlete Eligibility Condition Form. Only NOCs recognized by Panam Sports whose national swimming federations are affiliated with the International Swimming Federation (FINA) and the Union Americana de Natación (UANA) may enter athletes in the Cali 2021 Junior Pan American Games. -

Urban Forced Removals in Rio De Janeiro and Los Angeles: North-South Similarities in Race and City

\\jciprod01\productn\I\IAL\44-2\IAL207.txt unknown Seq: 1 1-NOV-13 13:43 337 Urban Forced Removals in Rio de Janeiro and Los Angeles: North-South Similarities in Race and City Constance G. Anthony1 In April of 2010, Rio de Janeiro’s mayor, Eduardo Paes, announced that two in-city, poor, and largely Afro-Brazilian neighborhoods, Morro dos Prazeres and Laboriaux, would be cleared and all inhabitants would be forced to move.2 Despite dev- astating winter storms, which had indicated again the precarious- ness of Rio’s hillside favelas, this was not really new news.3 Rio’s favelas have experienced a century of forced removal.4 The early neighborhoods were built in historically undesirable, beautiful, but steeply inaccessible parts of Rio, and today these are impor- tant pieces of Rio’s real estate.5 For more than a century, many such favelas have allowed poor, working class Afro-Brazilians immediate access to the city below.6 While there are incredible challenges with living in neighborhoods cut off from good, or in some cases even basic, city services and infrastructure, the resources of the city at large continued to make these neighbor- hoods highly desirable for those who lived, and as importantly, worked there.7 Cities across the globe use this mandate for the forced move- ment of poor populations out of in-city urban neighborhoods.8 1. Constance G. Anthony is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Seattle University. She received her PhD at the University of California, Berkeley. She has published a book on the politics of international aid and technology transfer with Columbia University Press, and articles on US science policy, refugees, and famine in Africa as well as the philosophical foundations of US interventionism. -

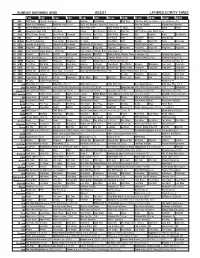

Sunday Morning Grid 8/22/21 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/22/21 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News Graham Bull Riding PGA Tour PGA Tour Golf The Northern Trust, Final Round. (N) 4 NBC Today in LA Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å 2021 AIG Women’s Open Final Round. (N) Race and Sports Mecum Auto Auctions 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch David Smile 7 ABC Eyewitness News 7AM This Week Ocean Sea Rescue Hearts of Free Ent. 2021 Little League World Series 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Paid Prog. Mike Webb Harvest AAA Danette Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Mercy Jack Hibbs Fox News Sunday The Issue News Sex Abuse PiYo Accident? Home Drag Racing 1 3 MyNet Bel Air Presbyterian Fred Jordan Freethought In Touch Jack Hibbs AAA NeuroQ Grow Hair News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Fashion for Real Life MacKenzie-Childs Home MacKenzie-Childs Home Quantum Vacuum Å COVID Delta Safety: Isomers Skincare Å 2 2 KWHY Programa Resultados Revitaliza Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa Programa 2 4 KVCR Great Scenic Railway Journeys: 150 Years Suze Orman’s Ultimate Retirement Guide (TVG) Great Performances (TVG) Å 2 8 KCET Darwin’s Cat in the SciGirls Odd Squad Cyberchase Biz Kid$ Build a Better Memory Through Science (TVG) Country Pop Legends 3 0 ION NCIS: New Orleans Å NCIS: New Orleans Å Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) 3 4 KMEX Programa MagBlue Programa Programa Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN R. -

Información Histórica Del Cine Argentino

Revista de Historia Americana y Argentina, Nº 39, 2002,U.N.de Cuyo ___________________________________________________________ INFORMACIÓN HISTÓRICA DEL CINE ARGENTINO. PRIMERA PARTE: EL CINE ARGENTINO DESDE SUS COMIENZOS HASTA 1970 María Inés Dugini de De Cándido Introducción La historia del cine no puede separarse de la vida, las ideas y las pasiones de los hombres. Tampoco puede separarse de su contexto. Al estudiar sus obras y sus hombres no podemos olvidar que el cine es parte del conocimiento de nuestro país. Es un elemento de valor en el reflejo de su his- toria y sus costumbres que realmente integra su cultura. El cine es un referente de gran trascendencia, para el conocimiento o recreación histórica. Su adecuada utilización nos permite acceder a interesantes planteos de nuestra historia. Cabe destacar que un film puede o no tratar un hecho histórico pero la trama o guión nos dará una excelente pesquisa de un tiempo político, social y cultural. El cine ocupa un lugar muy importante en el panorama del arte y la cultura contemporánea, y también un instrumento pedagógico y científico en las universidades. Las películas constituyen excelentes documentos históricos, son magníficas fuentes impresas. Se pueden mencionar -además- antiguos noticieros o "actualidades" (ahora históricos), reportajes a personajes gravitantes en un momento o a personas que los han conocido, películas etnológicas, de las cuales hay abundante material en la UNESCO. Otro aspecto muy valioso constituyen las películas de reconstrucciones socio-históricas contemporáneas o no, de interpretaciones de la realidad, de políticas y de ideologías. El conocimiento que a través de un film podemos obtener, considerado como fuente impresa, vale decir el cine como laboratorio histórico. -

Caracas, Venezuela Power, Scalability, and IT Global Connections for Your Business

Data Center Services — Caracas, Venezuela Power, scalability, and IT global connections for your business. Business solutions Site specifications The Premier Elite LumenSM Data Center in Caracas, • Raised floor of 80 cm allows tray wiring installation Venezuela offers computer platforms that support across three different levels everything from secure storage and backup systems to • Cabling system in compliance with ANSI / TIA / EIA cloud services. With minimum investment, you can benefit Standard 568A from a robust IT infrastructure and access to proven global communications. This can help reduce internal operating costs, administration and management. Access control • Security system with open door sensors throughout the building Global support • CCTV images recorded and archived for seven (7) days Data Center Services provide direct connectivity with the • Types of entry controls present: proximity cards and outstanding global support of Lumen. biometric sensors Facilities where needed Electrical power supply Lumen has more than 350 data center facilities in the US, • Power can be supplied in 110-220 V AC or -48 V DC, as Europe and Latin America, and provides network access required by the customer to more than 60 countries worldwide. Connectivity among sites is available through Lumen global network. Management services Lumen has the ability to integrate and manage facilitates governance of the complex and dynamic environments in which IT departments operate. Get the raw bandwidth, transparency and control your applications demand. The Lumen Wavelength service lets you choose among varying speeds, interfaces, routes and protection options. Our data centers Lumen data centers are specially designed facilities to safely house and maintain IT and communications equipment. -

Daniel Tinayre En Un Contexto De Cambios (1945-1955) Rodolfo Rodriguez UNNOBA [email protected] Resumen: El Amor Hacia

Daniel Tinayre en un contexto de cambios (1945-1955) Rodolfo Rodriguez UNNOBA [email protected] Resumen: El amor hacia la literatura policial y el cine de los años 30- influido por diversas corrientes de vanguardias- determinaron la elección del cine como camino de expresión de uno de los más talentosos directores de nuestro séptimo arte, lamentablemente incomprendido por sus contemporáneos. Luego de dos colaboraciones en París y de trabajar como asesor, decide filmar solo a partir de 1934 cristalizando lo que sería su primer filme, en el que aborda una temática histórica: Bajo la Santa Federación (estrenado en 1935), a pocos años de que el cine silente diera lugar al parlante y sonoro. No es, sin embargo lo que consideramos la primera etapa lo que pretendemos analizar, sino la segunda, que coincide con el ascenso y caída del primer peronismo, es decir el período comprendido entre 1945-1955, donde el realizador concretó 8 películas. Encabalgado en el marco genérico del melodrama- policial, psicológico, carcelario o la comedia- sus mejores aportes se produjeron en un período de cambios generales que le permitieron crear entrelazando ficción y realidad. Dentro de aquel marco cronológico, Tinayre logró el aplauso de los estratos medios y populares, que gustaban de la calidad de su cine y de algunos pocos críticos. Posaremos nuestra mirada en Camino del infierno (codirector junto a Saslavsky); A sangre fría; Pasaporte a Río; Danza del fuego y Deshonra. Sin dudas 5 clásicos del melodrama, por donde es perceptible ver críticas a una sociedad y laudatorias expresiones, que no eran sino emergentes de una Nueva Argentina. -

Entre El Éxodo Y La Invasión. La Experiencia De Chilefilms En La Mirada De La Prensa Chilena Y Argentina

2020. Revista Encuentros Latinoamericanos, segunda época. Vol. IV, Nº 2, julio/diciembre ISSN1688-437X DOI----------------------------------- Entre el éxodo y la invasión. La experiencia de Chilefilms en la mirada de la prensa chilena y argentina Between Exodus and Invasion. The Experience of Chilefilms as seen by Chilean and Argentine Press Alejandro Kelly-Hopfenblatt1 Instituto de Artes del Espectáculo «Raúl H. Castagnino», Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires/CONICET [email protected] María Paz Peirano Olate2 Universidad de Chile [email protected] Recibido: 17.07.20 Aceptado: 21.11.20 Resumen En los años cuarenta el gobierno chileno, impulsado por un espíritu modernizador, creó Chilefilms, una empresa con la que se esperaba integrarse al campo de las industrias fílmicas internacionales. Sin embargo, su desarrollo devino en un fracaso que fue asociado usualmente a su impronta cosmopolita y extranjerizante y a la cuantiosa presencia de argentinos en los distintos ámbitos de su producción. Este artículo propone revisar los 1 Proyecto Posdoctoral Conicet (Financia Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas de Argentina, Conicet, ejecuta Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad de Buenos Aires). «La comedia sofisticada como una estrategia de mediación del proceso modernizador: la conformación de un género con dimensiones trasnacionales en el cine latinoamericano clásico» (2017-2020). 2 Proyecto PAI Comisión Nacional de Investigación Científica y Tecnológica (Conicyt) n.º 79170064 (Financia ANID, ejecuta ICEI Universidad de Chile) «Cartelera histórica. Estudio de exhibición y recepción de cine en Santiago entre 1918 y 1969» (2018-2020). 26 2020|ENCLAT. Revista Encuentros Latinoamericanos. Dossier: Sección Estudios de la Cultura discursos que se construyeron alrededor de Chilefilms en la prensa chilena y argentina de la época y la historiografía posterior.