Download for the Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LAM Approach to Digital Game Preservation And

Drawing Things Together: Understanding the Challenges and Opportunities of a Cross- LAM Approach to Digital Game Preservation and © Centrum för kulturpolitisk forskning Exhibition Nordisk Kulturpolitisk Tidsskrift, ISSN Online: 2000-8325 vol. 22, Nr. 2-2019 s. 332–354 Patrick Prax Dr. Patrick Prax is assistant professor at the Department of Game Design at Uppsala DOI: https://doi.org/10.18261/ University. Patrick has a PhD in Media Studies from the Informatics and Media Department issn.2000-8325/-2019-02-08 at Uppsala University. Patrick´s work centers around digital games as participatory culture. He has written his dissertation about co-creative game design and has given a Uppsala RESEARCH PUBLICATION University TEDx talk about the topic. He has been working in a research project at the Swedish National Museum of Science and Technology and writes about participation in preservation and exhibition of games as cultural heritage. He is also serving as board member for the Cultural Heritage Incubator of the Swedish National Heritage Board. [email protected] Björn Sjöblom Björn Sjöblom, PhD, is an assistant professor at the Department of Child and Youth Studies at Stockholm University. He works in a variety of areas related to discourse and interaction, both by and about children and youth. For the most part, his studies focus on interaction in various forms of digital media, especially in games. His research includes studies of teenagers in internet cafés, interaction in videomediated gaming,(such as on Youtube), and representations of children in digital games. Of special interest are also questions of digital media as cultural heritage, and of young people’s relationship to esport. -

454 Ajalugu Piltides Sisu ENG 2012.Pdf

8000 BC 1000 BC to 1000 AD 1154 1100s 1200s 1219 13th–16th c 14th–15th c 1500s 1523–4 late 1500s 1600s 1700s early 1800s 1857–1869 late 1800s 1905–18 1918 1919–20 1920s 1930s 1940 1941 1941 1944 1949 1940s–50s 1956–68 1970s late 1980s 1991 1991 1992 1994 2004–2012 People have lived in this part of the world for more than 10 000 years. The reindeer- hunting ancestors of present- day Estonians were probably the first humans to move to the virgin land exposed by the retreating ice. Arguably, it is hard to find another nation in Europe who has stayed this long in one place. Tools of the Stone Age hunters from the Pulli 8000 BC camp site. 8000 BC 1000 BC to 1000 AD 1154 1100s 1200s 1219 13th–16th c 14th–15th c 1500s 1523–4 late 1500s 1600s 1700s early 1800s 1857–1869 late 1800s 1905–18 1918 1919–20 1920s 1930s 1940 1941 1941 1944 1949 1940s–50s 1956–68 1970s late 1980s 1991 1991 1992 1994 2004–2012 1000 BC to The Holy Lake in the 1000 AD Standing next to the crater Kaali meteorite crater made by the only meteorite to fall on a densely settled in Saaremaa: a major region in the historical era – during the Bronze Age place of worship of the Mediterranean – it is hard not to contemplate for the ancients of how the people of the past might have sought spiritual Northern Europe? guidance at this very spot for hundreds of years. ERGO IAM DEXTRO SUEBICI In 1154, Estonia was depicted on MARIS LITORE AESTIORUM a world map for 1154 the first time. -

Konrad Mägi 9

SISUKORD CONTENT 7 EESSÕNA 39 KONRAD MÄGI 9 9 FOREWORD 89 ADO VABBE 103 NIKOLAI TRIIK 13 TRADITSIOONI 117 ANTS LAIKMAA SÜNNIKOHT 136 PAUL BURMAN 25 THE BIRTHPLACE OF 144 HERBERT LUKK A TRADITION 151 ALEKSANDER VARDI 158 VILLEM ORMISSON 165 ENDEL KÕKS 178 JOHANNES VÕERAHANSU 182 KARL PÄRSIMÄGI 189 KAAREL LIIMAND 193 LEPO MIKKO 206 EERIK HAAMER 219 RICHARD UUTMAA 233 AMANDUS ADAMSON 237 ANTON STARKOPF Head tartlased, Lõuna-Eesti väljas on 16 tema tööd eri loominguperioodidest. 11 rahvas ja kõik Eesti kunstisõbrad! Kokku on näitusel eksponeeritud 57 maali ja 3 skulptuuri 17 kunstnikult. Mul on olnud ammusest ajast soov ja unistus teha oma kunstikollektsiooni näitus Tartu Tänan väga meeldiva koostöö eest Tartu linnapead Kunstimuuseumis. On ju eesti maalikunsti sünd 20. Urmas Klaasi ja Tartu linnavalitsust, Signe Kivi, sajandi alguses olnud olulisel määral seotud Tartuga Hanna-Liis Konti, Jaanika Kuznetsovat ja Tartu ja minu kunstikogu tuumiku moodustavadki sellest Kunstimuuseumi kollektiivi. Samuti kuulub tänu perioodist ehk eesti kunsti kuldajast pärinevad tööd. meie meeskonnale: näituse kuraatorile Eero Epnerile, kujundajale Tõnis Saadojale, graafilisele Tartuga on seotud mitmed meie kunsti suurkujud, disainerile Tiit Jürnale, meediaspetsialistile Marika eesotsas Konrad Mägiga. See näitus on Reinolile ja Inspiredi meeskonnale, keeletoimetajale pühendatud Eesti Vabariigi 100. juubelile ning Ester Kangurile, tõlkijale Peeter Tammistole ning Konrad Mägi 140. sünniaastapäeva tähistamisele. koordinaatorile Maris Kunilale. Suurim tänu kõigile, kes näituse õnnestumisele kaasa on aidanud! Näituse kuraator Eero Epner on samuti Tartus sündinud ja kasvanud ning lõpetanud Meeldivaid kunstielamusi soovides kunstiajaloolasena Tartu Ülikooli. Tema Enn Kunila nägemuseks on selle näitusega rõhutada Tartu tähtsust eesti kunsti sünniloos. Sellest mõttest tekkiski näituse pealkiri: „Traditsiooni sünd“. -

Estonian Academy of Sciences Yearbook 2018 XXIV

Facta non solum verba ESTONIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES YEARBOOK FACTS AND FIGURES ANNALES ACADEMIAE SCIENTIARUM ESTONICAE XXIV (51) 2018 TALLINN 2019 This book was compiled by: Jaak Järv (editor-in-chief) Editorial team: Siiri Jakobson, Ebe Pilt, Marika Pärn, Tiina Rahkama, Ülle Raud, Ülle Sirk Translator: Kaija Viitpoom Layout: Erje Hakman Photos: Annika Haas p. 30, 31, 48, Reti Kokk p. 12, 41, 42, 45, 46, 47, 49, 52, 53, Janis Salins p. 33. The rest of the photos are from the archive of the Academy. Thanks to all authos for their contributions: Jaak Aaviksoo, Agnes Aljas, Madis Arukask, Villem Aruoja, Toomas Asser, Jüri Engelbrecht, Arvi Hamburg, Sirje Helme, Marin Jänes, Jelena Kallas, Marko Kass, Meelis Kitsing, Mati Koppel, Kerri Kotta, Urmas Kõljalg, Jakob Kübarsepp, Maris Laan, Marju Luts-Sootak, Märt Läänemets, Olga Mazina, Killu Mei, Andres Metspalu, Leo Mõtus, Peeter Müürsepp, Ülo Niine, Jüri Plado, Katre Pärn, Anu Reinart, Kaido Reivelt, Andrus Ristkok, Ave Soeorg, Tarmo Soomere, Külliki Steinberg, Evelin Tamm, Urmas Tartes, Jaana Tõnisson, Marja Unt, Tiit Vaasma, Rein Vaikmäe, Urmas Varblane, Eero Vasar Printed in Priting House Paar ISSN 1406-1503 (printed version) © EESTI TEADUSTE AKADEEMIA ISSN 2674-2446 (web version) CONTENTS FOREWORD ...........................................................................................................................................5 CHRONICLE 2018 ..................................................................................................................................7 MEMBERSHIP -

News in Brief

NEWS IN BRIEF PROFESSOR KAZYS GRIGAS: 90TH BIRTH ANNIVERSARY Kazys Grigas was born into a farmers’ family in Pagiriai, Kaunas district, on March 1, 1924. He graduated from a gardening and floriculture school in Kaunas, and attended Vilkija Gymnasium. In 1944 he entered Kaunas Theological Seminary to avoid enlisting into the Soviet army. In 1945, after having taken the entrance examinations, he was admitted to the Faculty of History and Philology at Kaunas National Vytautas Magnus University. When ideological cleansing started at the university in 1948, K. Grigas was expelled with an entry in his personal file: “Expelled from Kaunas University for behaviour incompatible with a Soviet student’s honour and duties”. Later on, K. Grigas studied at Kaunas Teachers Seminary, took librarianship equiva- lency examinations, taught at a gymnasium (Lithuanian and Latin languages), and worked at the bookbindery at the library of the History Institute of the Academy of Sciences in Vilnius. In 1951 he took equivalency examinations and graduated from Vilnius University. In 1954 K. Grigas started working at the Lithuanian Institute of Language and Literature (now Lithuanian Literature and Folklore Institute), where he became engaged in the field of folkloristics. K. Grigas spent the years from 1990 to 1998 teaching: he taught a course in paremiology at Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, and later on a comparative folkloristics course at Vilnius University. K. Grigas translated various works of fiction, for instance, L. Carroll’sAlice’s Adventures in Won- derland (1957) and Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass (1991, in collaboration with J. Lapienytė), R. -

Digra 2020 CONFERENCE

Plan to hold the DiGRA 2020 CONFERENCE 3-6 June 2020 in Tampere, Finland Plan to hold the DIGRA 2020 CONFERENCE 3-6 June 2020 in Tampere, Finland CONTENTS In Brief ......................................................................................................................................3 Venue........................................................................................................................................3 Conference .................................................................................................................................4 Travel and Accommodation ..............................................................................................................6 Organization ................................................................................................................................7 Publicity & Dissemination ................................................................................................................9 Other Considerations ......................................................................................................................9 2 IN BRIEF DiGRA 2020 will be organised in Tampere, Finland; the conference dates are 3-6 June 2020 (with a pre-conference day in 2nd June 2020). Co-hosted by the Centre of Excellence in Game Culture Studies (CoE-GameCult) and three universities, the theme of DiGRA 2020 is set as Play Everywhere. The booked venues are LINNA building of Tampere University, and Tampere Hall – the largest conference centre in the -

Mess in the City at the Moment, It's the New Tram Network Being Built

mess in the city at the moment, it’s the new tram network being built Moro! *) -something that we worked for years to achieve and are really proud of. Welcome to Tampere! So welcome again to our great lile city! We are prey sure that it’s the best Tampere is the third largest city and the second largest urban area in Finland, city in Finland, if not in the whole Europe -but we might be just a lile bit with a populaon of closer to half a million people in the area and just over biased about that… We hope you enjoy your stay! 235 000 in the city itself. The Tampere Greens Tampere was founded in 1779 around the rapids that run from lake Näsijärvi to lake Pyhäjärvi -these two lakes and the rapids very much defined Tampere and its growth for many years, and sll are a defining characterisc of the *) Hello in the local dialect city. Many facories were built next to the energy-providing Tammerkoski rapids, and the red-brick factories, many built for the texle industry, are iconic for the city that has oen been called the Manchester of Finland -or Manse, as the locals affeconately call their home town. Even today the SIGHTS industrial history of Tampere is very visible in the city centre in the form of 1. Keskustori, the central square i s an example of the early 1900s old chimneys, red-brick buildings and a certain no-nonsense but relaxed Jugend style, a northern version of Art Nouveau. Also the locaon of atude of the local people. -

Ment of Collections in Tampere Museums

NORDI S K M US EOLOGI 1998•2, S . 51-68 How TO MANAGE COLLECTIONS? - THE PROBLEM OF MANAGE MENT OF COLLECTIONS IN TAMPERE MUSEUMS Ritva Palo-oja & Leena Willberg What do you do, when collections include 200, 000 objects, and only halfof them are within the management system? What do you do with objects that have been damaged by fire or in transfers between collections? These questions prompted the collection management team of Tampere Museums to develop a value classification system in 1994. This system has been applied since, and has proved to be a practical tool for collection management. The system has already been refined through experience. We hope that this article will provoke discussion and motivate museums to develop common collection management methods. TAMPERE MUSEUMS further strengthened by the establishment of a railway network. The first railway con The collection policy of the Tampere nection was opened in 1876 between Museums is to accumulate the cultural Hameenlinna and Tampere. Industrialists heritage of the Tampere Region, maintain realised the power potential of the Tammer it and put it on display. koski Rapids, and one by one the textile The city of Tampere was founded in industry, the engineering industry and the 1779, and is the largest inland city in paper and shoe industries started to develop Scandinavia. It is located on the historical and became important branches of Finnish junction of centuries old waterways and industry as a whole. After decades of struc roads on the isthmus of lakes Nasijarvi and tural change, Tampere has become an Pyhajarvi, on both sides of the Tammer important centre in the IT industry and a koski Rapids. -

Program ICR Conference 2017

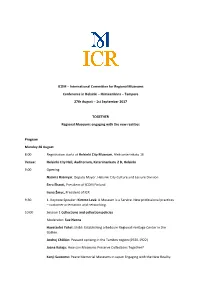

ICOM – International Committee for Regional Museums Conference in Helsinki – Hämeenlinna – Tampere 27th August – 1st September 2017 TOGETHER Regional Museums engaging with the new realities Program Monday 28 August 8:00 Registration starts at Helsinki City Museum, Aleksanterinkatu 16 Venue: Helsinki City Hall, Auditorium, Katariinankatu 2 B, Helsinki 9:00 Opening Nasima Rasmyar, Deputy Mayor, Helsinki City Culture and Leisure Division Eero Ehanti, President of ICOM Finland Irena Žmuc, President of ICR 9:30 1. Keynote Speaker: Kimmo Levä: A Museum is a Service. New professional practices – customer orientation and networking. 10:00 Session 1 Collections and collection policies Moderator: Sue Hanna Havatzelet Yahel: Shibli: Establishing a Bedouin Regional Heritage Center in the Galilee. Andrej Chilikin: Peasant uprising in the Tambov region (1920-1922). Jaana Kataja: How can Museums Preserve Collections Together? Kenji Saotome: Peace Memorial Museums in Japan Engaging with the New Reality. 11:00 Coffee 11:15 Session 2 Collections and collection policies Moderator: Tuulia Tuomi Irena Žmuc and Barbara Savenc: New Reality – New Collection? Blanca Gonzalez: From one century to another. Four museums in Merida. 11:45 Kenji Saotome: Presentation of ICOM General in Kyoto 2019 12:15 Discussion 12:30 Tiina Merisalo: The New Helsinki City Museum – The Museum of the Year in Finland 2017 12:45 Lunch 13:45 Helsinki City Museum guided tour 15:00 Session 3 Topographies of Fear, Hope and Anger Moderator: Jane Legget 15:00 2. Keynote Speaker: Jette Sandahl: Topographies of Fear, Hope and Anger 15:45 Round Table Workshop The ICOM Committee of Museum Definition, Prospects and Potentials is running a series of round-tables across the world to explore the future of museums and the shared, but also the profoundly dissimilar conditions, values and practices of museums in diverse and rapidly changing societies. -

Beyond the Hack Squat: George Hackenschmidt' S Forgotten Legacy As a Strength Training Pioneer

August 2013 Iron Game History Beyond the Hack Squat: George Hackenschmidt' s Forgotten Legacy as a Strength Training Pioneer FLORIAN HEMME AND JAN TODD* The University of Texas at Austin But, as will be seen, it has not been my design to confine myself to laying down a series ofmles for strong men and athletes only: my object in writing this book has been rather to lay before my read ers such data as may enable them to secure health as well as strength. Health can never be divorced from strength. The second is an inevitable sequel to the first. A man can only fortify himself against disease by strengthening his body in such manner as will enable it to defy the attacks of any mala dy.! -George Hackenschmidt in The Way to Live Born in Dorpat, Estonia on 2 August 1878, his unique training philosophy and "system. "2 In fact, George (originally Georg, sometimes spelled Georges) Hackenschmidt became a revered authority in the field Karl Julius Hackenschmidt was one of the most admired of physical culture and fitness, yet maintained a marked and successful Greco-Roman and Catch-as-Catch-Can ly different perspective from that of the two most wrestlers at the beginning of the twentieth century. Gift famous fitness entrepreneurs of the early twentieth cen ed with extraordinary physical capabilities that seemed tury-Eugen Sandow (1867-1925) and Bernarr Macfad to far exceed those of the average man, he rose to star den (1868-1955).3 The fact that Hackenschmidt's ideas dom in the early 1900s through a captivating mixture of on exercise were so different than those of Sandow and overwhelming ring presence, explosive power, sheer Macfadden-both of whom established magazines, strength, and admirable humility. -

Tampere Product Manual 2020

Tampere Product Manual 2020 ARRIVAL BY PLANE Helsinki-Vantaa Airport (HEL) 180 km (2 hours) from Tampere city center Tampere-Pirkkala Airport (TMP) 17 km from Tampere city center Airlines: Finnair, SAS, AirBaltic, Ryanair Transfer options from the airport: Bus, taxi, car hire 2 CATEGORY Table of Contents PAGE PAGE WELCOME TO TAMPERE ACCOMMODATION Visit Tampere 5 Lapland Hotels Tampere 43 Visit Tampere Partners 6 Holiday Inn Tampere – Central Station 43 Top Events in Tampere Region 7 Original Sokos Hotel Villa 44 Tampere – The World’s Sauna Capital 8 Solo Sokos Hotel Torni Tampere 44 Top 5+1 Things to Do in Tampere 9 Original Sokos Hotel Ilves 45 Quirky Museums 10+11 Radisson Blu Grand Hotel Tammer 45 Courtyard Marriott Hotel 46 ACTIVITIES Norlandia Tampere Hotel 46 Adventure Apes 13 Hotel-Restaurant ArtHotel Honkahovi 47 Amazing City 14 Hotel-Restaurant Mänttä Club House 47 Boreal Quest 15 Hotel Mesikämmen 48 Ellivuori Resort 49 Dream Hostel & Hotel 48 Grr8t Sports 16 Ellivuori Resort - Hotel & restaurant 49 Hapetin 17 Hotel Alexander 50 Hiking Travel, Hit 18+19 Mattilan Majatalo Guesthouse 51 Villipihlaja 20 Mökkiavain – Cottage Holidays 52 Kangasala Arts Centre 20 Niemi-Kapee Farm 52 Korsuretket 21 Wilderness Boutique Manor Rapukartano 53 Kelo ja kallio Adventures 22 Petäys Resort 54 Mobilia, Automobile and road museum 22 Vaihmalan Hovi 56 Moomin Museum 23 Villa Hepolahti 57 Matrocks 24+25 Taxi Service Kajon 25 FOOD & BEVERAGE Petäys Resort 55 Cafe Alex 50 Pukstaavi, museum of the Finnish Book 26 Restaurant Aisti 59 The House of Mr. -

Impact of Tampere Region Festivals and Cultural Attractions in 2013

DEVELOPING CULTURAL TOURISM IN THE TAMPERE REGION Impact of Tampere Region Festivals and Cultural Attractions in 2013 Introduction In 2012–2014, Tampere Region Festivals – Pirfest ry and Innolink Research Oy carried out a survey on the regional economic impact of cultural tourism and the quality of tourist attractions in the Tampere region. The survey was carried out as a visitor survey combined with visitor information received from the attractions. It involved 37 member festivals of Pirfest ry/Tampere Region Festivals, 34 cultural and tourist attractions in the Tampere region and 13 hotels. The attractions surveyed were located in 10 different municipalities in the Tampere region. The list of participants is included at the end of this report. The visitor survey was completed by 13,523 people, so it was exceptionally extensive in scope. According to the survey, the festivals and attractions attracted a total of 2.5 million visitors, who contributed €253 million to the local economy. Of this, €139.3 million consisted of tourism income brought by tourists from outside the Tampere region and €113 million was local tourism income from within the region. The Finnish Tourist Board defines cultural tourism as follows: “Cultural tourism produces tourism products and services and offers them on business grounds to locals and people from else- where, respecting regional and local cultural resources. The purpose is to create great experiences and give people the chance to get to know these cultural resources, learn from them or participate in them. This strengthens the formation of people’s identity and their understanding and appreciation of both their own culture and other cultures.” MIKKO KESÄ, RESEARCH & SALES DIRECTOR AT INNOLINK RESEARCH OY, STATES THE FOLLOWING ON THE RELIABILITY OF THE SURVEY: The survey was completed by over 13,000 respondents, so recreational services; other spending).