Bringing the Ports and Port Diplomacy Back-In 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hongkong a Study in Economic Freedom

HongKOng A Study In Economic Freedom Alvin Rabushka Hoover Institution on War, Revolution and Peace Stanford University The 1976-77 William H. Abbott Lectures in International Business and Economics The University of Chicago • Graduate School of Business © 1979 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. ISBN 0-918584-02-7 Contents Preface and Acknowledgements vn I. The Evolution of a Free Society 1 The Market Economy 2 The Colony and Its People 10 Resources 12 An Economic History: 1841-Present 16 The Political Geography of Hong Kong 20 The Mother Country 21 The Chinese Connection 24 The Local People 26 The Open Economy 28 Summary 29 II. Politics and Economic Freedom 31 The Beginnings of Economic Freedom 32 Colonial Regulation 34 Constitutional and Administrative Framework 36 Bureaucratic Administration 39 The Secretariat 39 The Finance Branch 40 The Financial Secretary 42 Economic and Budgetary Policy 43 v Economic Policy 44 Capital Movements 44 Subsidies 45 Government Economic Services 46 Budgetary Policy 51 Government Reserves 54 Taxation 55 Monetary System 5 6 Role of Public Policy 61 Summary 64 III. Doing Business in Hong Kong 67 Location 68 General Business Requirements 68 Taxation 70 Employment and Labor Unions 74 Manufacturing 77 Banking and Finance 80 Some Personal Observations 82 IV. Is Hong Kong Unique? Its Future and Some General Observations about Economic Freedom 87 The Future of Hong Kong 88 Some Preliminary Observations on Free-Trade Economies 101 Historical Instances of Economic Freedom 102 Delos 103 Fairs and Fair Towns: Antwerp 108 Livorno 114 The Early British Mediterranean Empire: Gibraltar, Malta, and the Ionian Islands 116 A Preliminary Thesis of Economic Freedom 121 Notes 123 Vt Preface and Acknowledgments Shortly after the August 1976 meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society, held in St. -

China: 2020-2050

www.followcn.com China: 2020-2050 Foreword We are now at the start of 2017. As the world is celebrating the coming of 2017 among many possibilities, I am keeping an eye on an emerging superpower who is claiming to be in a dream of peace, development, cooperation and mutual benefit for all. China's GDP growth rate for 2016 as a whole will come in very close to 6.7%. The forecast for 2017 is clouded by the uncertainty in the United States over the economic and other policies to be adopted by Donald Trump when he assumes the office of President in January, according to a recent report by China Daily. China is still leading the world economy after thirty years of continuous development. Despite the many problems and concerns in the environment, corruption, government debt, soaring property markets, and others, there are positive signs as a source for domestic growth by private entrepreneurship, enhanced social well-being and family life under a more responsible government administration. This trend should continue in 2017, as governments at all levels are pushed hard to realize the national vision of creating an ecological civilization for many if not all. China is moving closer to its goal of building an all-round moderately prosperous society by 2020, inspired by the Chinese dream of the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation, according to Xinhua News Agency. June 25th 2016, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) in London released its long-term macroeconomic forecasts with key trends to 2050, stating that China will surpass the USA in gross domestic product (GDP) in 2026, and top ten economies in 2050 at the EIU’s projected market exchange rates, in descending order, will be China, USA, India, Indonesia, Japan, Germany, Brazil, Mexico, UK, and France. -

NUI MAYNOOTH MILITARY AVIATION in IRELAND 1921- 1945 By

L.O. 4-1 ^4- NUI MAYNOOTH QllftMll II hiJfiifin Ui Mu*« MILITARY AVIATION IN IRELAND 1921- 1945 By MICHAEL O’MALLEY THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PHD DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Supervisor of Research: Dr. Ian Speller JANUARY 2007 IRISH MILITARY AVIATION 1921 - 1945 This thesis initially sets out to examine the context of the purchase of two aircraft, on the authority of Michael Collins and funded by the second Dail, during the Treaty negotiations of 1921. The subsequent development of civil aviation policy including the regulation of civil aviation, the management of a civil aerodrome and the possible start of a state sponsored civil air service to Britain or elsewhere is also explained. Michael Collins’ leading role in the establishment of a small Military Air Service in 1922 and the role of that service in the early weeks of the Civil War are examined in detail. The modest expansion in the resources and role of the Air Service following Collins’ death is examined in the context of antipathy toward the ex-RAF pilots and the general indifference of the new Army leadership to military aviation. The survival of military aviation - the Army Air Corps - will be examined in the context of the parsimony of Finance, and the administrative traumas of demobilisation, the Anny mutiny and reorganisation processes of 1923/24. The manner in which the Army leadership exercised command over, and directed aviation policy and professional standards affecting career pilots is examined in the contexts of the contrasting preparations for war of the Army and the Government. -

View / Download 7.3 Mb

Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Janice Hyeju Jeong 2019 Abstract While China’s recent Belt and the Road Initiative and its expansion across Eurasia is garnering public and scholarly attention, this dissertation recasts the space of Eurasia as one connected through historic Islamic networks between Mecca and China. Specifically, I show that eruptions of -

Englischer Diplomat, Commissioner Chinese Maritime Customs Biographie 1901 James Acheson Ist Konsul Des Englischen Konsulats in Qiongzhou

Report Title - p. 1 of 348 Report Title Acheson, James (um 1901) : Englischer Diplomat, Commissioner Chinese Maritime Customs Biographie 1901 James Acheson ist Konsul des englischen Konsulats in Qiongzhou. [Qing1] Aglen, Francis Arthur = Aglen, Francis Arthur Sir (Scarborough, Yorkshire 1869-1932 Spital Perthshire) : Beamter Biographie 1888 Francis Arthur Aglen kommt in Beijing an. [ODNB] 1888-1894 Francis Arthur Aglen ist als Assistent für den Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Beijing, Xiamen (Fujian), Guangzhou (Guangdong) und Tianjin tätig. [CMC1,ODNB] 1894-1896 Francis Arthur Aglen ist Stellvertretender Kommissar des Inspektorats des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Beijing. [CMC1] 1899-1903 Francis Arthur Aglen ist Kommissar des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Nanjing. [ODNB,CMC1] 1900 Francis Arthur Aglen ist General-Inspektor des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Shanghai. [ODNB] 1904-1906 Francis Arthur Aglen ist Chefsekretär des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Beijing. [CMC1] 1907-1910 Francis Arthur Aglen ist Kommissar des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Hankou (Hubei). [CMC1] 1910-1927 Francis Arthur Aglen ist zuerst Stellvertretender General-Inspektor, dann General-Inspektor des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Beijing. [ODNB,CMC1] Almack, William (1811-1843) : Englischer Teehändler Bibliographie : Autor 1837 Almack, William. A journey to China from London in a sailing vessel in 1837. [Reise auf der Anna Robinson, Opiumkrieg, Shanghai, Hong Kong]. [Manuskript Cambridge University Library]. Alton, John Maurice d' (Liverpool vor 1883) : Inspektor Chinese Maritime Customs Biographie 1883 John Maurice d'Alton kommt in China an und dient in der chinesischen Navy im chinesisch-französischen Krieg. [Who2] 1885-1921 John Maurice d'Alton ist Chef Inspektor des Chinese Maritime Customs Service in Nanjing. -

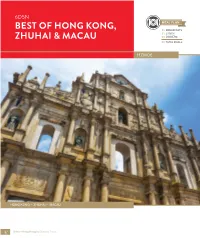

Best of Hong Kong, Zhuhai & Macau

6D5N MEAL PLAN BEST OF HONG KONG, 05 BREAKFASTS 01 LUNCH ZHUHAI & MACAU 03 DINNERS 09 TOTAL MEALS HZM06 HONG KONG – ZHUHAI – MACAU 82 China + Hong Kong by Dynasty Travel • Stanley Market – One of the most visited Hong Kong Street Markets. It is a great place to purchase both Western and SHENZHEN Chinese clothing as well as typical Chinese souvenirs. HONG KONG 2 • Victoria Peak Tour with one way tram ride – The highest point on Hong Kong Island, this has been city’s most exclusive ZHUHAI neighbourhood since colonial times back. Experience one of the world’s oldest and most famous funicular railways to the HONG KONG INTERNATIONAL highest point on Hong Kong Island. 2 ZHUHAI AIRPORT • Madame Tussauds – Meet with over 100 incredibly life like HONG KONG ISLAND wax figures from all around the world including Aaron Kwok, MACAU 1 Donnie Yen, Lee Min Ho, Cristiano Ronaldo, Doraemon, Hello Kitty and McDull. • Ladies Street – Popular street that sells various, low-priced START/END products and also other general merchandise. Breakfast – Local Dim Sum | Lunch – Poon Choi | N NIGHT STAY Dinner – Lei Yue Mun Seafood Dinner BY FLIGHT BY COACH DAY 3 BY CRUISE HONG KONG ZHUHAI • Meixi Royal Stone Archways – An archway to commemorate Chen Fang, who is the first Chinese consul general in Honolulu, DAY 1 was born in Meixi Village. SINGAPORE HONG KONG • Gong Bei Underground Shopping Complex – It is a huge Welcome to a unique experience! shopping mall integrated leisure, entertainment with catering. • Assemble at Singapore Changi Airport for our flight to Hong There are lots of stores engaged in clothes and local snacks, Kong. -

Wooster – a Charter City Charter Ballot Performance Revisions Dashboard

CITY NEWSLETTER Fall 2020 What’s Inside WOOSTER – A CHARTER CITY CHARTER BALLOT PERFORMANCE REVISIONS DASHBOARD Leaf Pick Up | Trick or Treat | DORA | Recycling Info | Hazardous Waste Collection Mayor Breneman’s Message As we are all aware, COVID’s appearance in our community started quite a few months ago. Even though the virus is still present in our city and county, and we City Newsletter | Fall 2020 have experienced sickness and tragically loss, I want to focus on the many good things we have going for us. We are truly blessed to live, work, and have family and friends Inside This Edition in this beautiful city and county we call home. Message from the Mayor 1 Please take time to step away from the news media, Wooster – A Charter City 2 election turmoil, and daily briefings to reflect on what Ballot Summaries 3 makes Wooster and our agrarian heritage so special in Performance Dashboard 9 life today. We are far better off living through this virus than what was originally predicted. Our city is operating well in all of our critical Trick or Treat 13 service lines (Hospital, Police, Fire/EMS, Water, Wastewater, Maintenance and Getting Noticed 14 Utilities), and we have a solid economy fueling our lives and needs. Santa’s Mailbox 14 Take a moment to enjoy all the good that surrounds us; fall colors, starry nights, Recycling 15 cool weather, friends and family, holidays, and our health. There are many things Hazardous Waste 15 that try to pull us down; make sure you balance those with the abundance of good Infrastructure Updates 16 that surrounds every day! Normal life is coming. -

Untitled [Daniel Williamson on Britain, Ireland, and The

Ian S. Wood. Britain, Ireland, and the Second World War. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2010. ix + 238 pp. $95.00, cloth, ISBN 978-0-7486-2327-3. Reviewed by Daniel C. Williamson Published on H-Albion (August, 2011) Commissioned by Thomas Hajkowski (Misericordia University) Ian S. Wood’s Britain, Ireland, and the Second Irish Free State was now known, cut many of the World War provides a valuable survey of the im‐ symbolic ties that had bound it to the United King‐ pact that the war had on Ireland and how it af‐ dom. Even before war broke out, de Valera was fected relations among the governments of Eire, preparing for Irish neutrality by insisting on the Northern Ireland, and Great Britain. The author return of the Treaty Ports to Eire, a policy that covers a number of major topics including the Wood characterizes as “an affirmation of full neutrality of Eire, the impact that the war had on sovereignty” (p. 26). Northern Ireland, the response of the IRA to the Historians have long understood that Irish conflict, and Britain’s relations with the Irish gov‐ neutrality, or more accurately, nonbelligerence, ernments on both sides of the border. tilted strongly in favor of the Allies. Dublin coop‐ Eamon de Valera’s determination to keep Eire erated with Britain on intelligence matters, sup‐ officially neutral is given a central place in Wood’s plied the Allies with valuable weather informa‐ study. “With our history, with our experience of tion, and made secret military plans to coordinate the last war and with part of our country still un‐ with British forces in case of a German invasion justly severed from us, we felt that no other deci‐ of Ireland. -

Western Australia's International Resources

WESTERN AUSTRALIA’S INTERNATIONAL RESOURCES DEVELOPMENT MAGAZINE March–May 2004 $3 (inc GST) Print post approved PP 665002/00062 post approved Print China WESTERN AUSTRALIAN OFFICES Department of Industry and Resources Mineral House • 100 Plain Street • EAST PERTH WA 6004 Tel: +61 8 9222 3333 • Fax: +61 8 9222 3430 www.doir.wa.gov.au Investment Services FROM THE MINISTER 168–170 St Georges Terrace • PERTH Western Australia 6000 Postal address: Box 7606 • Cloisters Square PERTH Western Australia 6850 Optimism with LNG Tel: +61 8 9327 5555 • Fax: +61 8 9222 3862 Email: [email protected] NG is vital as an emerging energy source at a time when there INTERNATIONAL OFFICES is concern about the longer-term sustainability of supply of Europe petroleum, issues about security of energy supplies generally, Government of Western Australia L and the need for the world to progress to less greenhouse-intensive European Office • 5th floor, Australia Centre Clive Brown, MLA Corner of Strand and Melbourne Place and polluting forms of energy. Minister for State LONDON WC2B 4LG • UNITED KINGDOM The Western Australian Government is optimistic that several Development Tel: +44 20 7240 2881 • Fax: +44 20 7240 6637 Email: [email protected] new LNG projects can be developed within the next two decades. India — Mumbai To maximise opportunities in LNG and related sectors, the Western Australian Trade Office Western Australian Government is focusing on four strategic areas 93 Jolly Maker Chambers No 2 9th floor, Nariman Point • MUMBAI 400 021 INDIA — developing a strong and competitive economy; providing Tel: +91 22 5630 3979/74/78 • Fax: +91 22 5630 3977 supportive infrastructure to projects; ensuring Government Email: [email protected] facilitation optimises outcomes for business, Government and the India — Chennai Western Australian Trade Office - Advisory Office community; and developing long-term relationships between all players as the basis for 1 Doshi Regency • 876 Poonamallee High Road ensuring mutually beneficial outcomes. -

Commonwealth Games Research

Updated Review of the Evidence of Legacy of Major Sporting Events: July 2015 social Commonwealth Games research UPDATED REVIEW OF THE EVIDENCE OF LEGACY OF MAJOR SPORTING EVENTS: JULY 2015 Communities Analytical Services Scottish Government Social Research July 2015 1. INTRODUCTION 1 Context of the literature review 1 Structure of the review 2 2. METHOD 3 Search strategy 3 Inclusion criteria 4 2015 Update Review Method 4 3. OVERVIEW OF AVAILABLE EVIDENCE 6 Legacy as a ‘concept’ and goal 6 London focus 7 4. FLOURISHING 8 Increase Growth of Businesses 8 Increase Movement into Employment and Training 13 Volunteering 17 Tourism Section 19 Conclusion 24 2015 Addendum to Flourishing Theme 25 5. SUSTAINABLE 28 Improving the physical and social environment 28 Demonstrating sustainable design and environmental responsibility 30 Strengthening and empowering communities 32 Conclusion 33 2015 Addendum to Sustainable Theme 33 6. ACTIVE 37 Physical activity and participation in sport 37 Active infrastructure 40 Conclusion 42 2015 Addendum to Active Theme 43 7. CONNECTED 44 Increase cultural engagement 44 Increase civic pride 46 Perception as a place for cultural activities 47 Enhance learning 49 Conclusion 49 2015 Addendum to Connected Theme 50 8. AREAS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH 51 9. CONCLUSIONS 52 10. REFERENCES 54 References 1st October 2013 to 30th September 2014 64 APPENDIX 67 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The aim of this evidence review is to establish whether major international multi-sport events can leave a legacy, and if so, what factors are important for making that happen. This edition of the original Kemlo and Owe (2014) review provides addendums to each legacy theme based on literature from 1st October 2013 to the end of September 2014. -

Investigation and Analysis of Architectural Styles in the Historical Center of Macau

Research report Research Report and Culture, 43(4), pp. 657-667. 23(2), pp. 3-16. Received April 21, 2020; Accepted October 19, 2020 [4] Loewy, R. (2002) Never leave well enough alone. [16] Akrich, M. (1992) The de-scription of technical Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. objects, in W. Bijker & J. Law [Eds] Shaping [5] Edgerton, D. (1999) From innovation to use: Ten technology/building society: Studies in INVESTIGATION AND ANALYSIS OF ARCHITECTURAL eclectic theses on the historiography of technology. sociotechnical change. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, History and Technology, 16, pp. 111-136. pp. 205-224. STYLES IN THE HISTORICAL CENTER OF MACAU [6] Williamson, B. (2009) The bicycle: considering [17] Norman, D. A. (2002) The design of everyday design in use, in H. Clark & D. Brody [Eds], Design things. New York : Basic Books. Yang Yang ZHANG*, Po Hsun WANG** studies: A reader. New York, NY: Berg, pp. 522-524. [18] Latour, B. (2005) Reassembling the social: An [7] Pinch, T. E., & Bijker, W. (1989) The social introduction to actor-network theory. Oxford: Oxford construction of facts and artifacts: Or how the University Press. * Graduate school of Urban Planning and Design, Faculty of Innovation and Design, City University of Macau, Macau ** Faculty of Innovation and Design, City University of Macau, Macau sociology of science and the sociology of technology [19] Conway, H. (Ed.) (1987) Design history: A student’s might benefit each other, in T.P. Bijker, W.T. Hughes, handbook. London, England: Routledge. & T.E. Pinch [Eds], The social construction of [20] Walker, J. (1989) Design history and the history of Abstract: The purpose of this study is to investigate and analyze the architectural styles of the Historical technological systems: New directions in the design. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS CORPORATE POWERS 2 GOVERNMENTAL ORGANIZATION 2 CITY MANAGER ALTERNATIVE 3 ELECTIONS 9 LEGISLATION 11 FINANCE 13 SCHEDULE 18 INDEX 22 CITY OF ROCKFORD CHARTER We, the people of the City of Rockford, pursuant to the authority granted by the Constitution and laws of the State of Michigan, in order to secure the benefits of efficient self-government and otherwise promote our common welfare, do hereby ordain and establish this Charter. CORPORATE POWERS Section 1. The municipal corporation now existing and known as the Village of Rockford, shall continue to be a body politic and corporate under the name City of Rockford, and include all territory described as follows: The whole of section thirty-six (36) in township nine (9) north of range eleven (11) west, and the fractional north half of the north half of section one (1) in township eight (8) north of range eleven (11) west, as originally incorporated as the Village of Rockford by Act No. 537 of the Local Acts of 1887, in Kent County, Michigan. Section 2. The City shall have power to exercise any and all of the powers which cities are, or may hereafter be, permitted to exercise or to provide in their charters under the constitution and laws of the State of Michigan, as fully and completely as though the powers were specifically enumerated herein, and to do any act to advance the interests of the City, the good government and prosperity of the municipality and its inhabitants, except for such limitations and restrictions as are provided in this Charter, and no enumeration of particular powers of the City in this Charter shall be held to be exclusive.