Millet and Modern Art Audio Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

16 Exhibition on Screen

Exhibition on Screen - The Impressionists – And the Man Who Made Them 2015, Run Time 97 minutes An eagerly anticipated exhibition travelling from the Musee d'Orsay Paris to the National Gallery London and on to the Philadelphia Museum of Art is the focus of the most comprehensive film ever made about the Impressionists. The exhibition brings together Impressionist art accumulated by Paul Durand-Ruel, the 19th century Parisian art collector. Degas, Manet, Monet, Pissarro, Renoir, and Sisley, are among the artists that he helped to establish through his galleries in London, New York and Paris. The exhibition, bringing together Durand-Ruel's treasures, is the focus of the film, which also interweaves the story of Impressionism and a look at highlights from Impressionist collections in several prominent American galleries. Paintings: Rosa Bonheur: Ploughing in Nevers, 1849 Constant Troyon: Oxen Ploughing, Morning Effect, 1855 Théodore Rousseau: An Avenue in the Forest of L’Isle-Adam, 1849 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Gleaners, 1857 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: The Angelus, c. 1857-1859 (Barbizon School) Charles-François Daubigny: The Grape Harvest in Burgundy, 1863 (Barbizon School) Jean-François Millet: Spring, 1868-1873 (Barbizon School) Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot: Ruins of the Château of Pierrefonds, c. 1830-1835 Théodore Rousseau: View of Mont Blanc, Seen from La Faucille, c. 1863-1867 Eugène Delecroix: Interior of a Dominican Convent in Madrid, 1831 Édouard Manet: Olympia, 1863 Pierre Auguste Renoir: The Swing, 1876 16 Alfred Sisley: Gateway to Argenteuil, 1872 Édouard Manet: Luncheon on the Grass, 1863 Edgar Degas: Ballet Rehearsal on Stage, 1874 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Ball at the Moulin de la Galette, 1876 Pierre Auguste Renoir: Portrait of Mademoiselle Legrand, 1875 Alexandre Cabanel: The Birth of Venus, 1863 Édouard Manet: The Fife Player, 1866 Édouard Manet: The Tragic Actor (Rouvière as Hamlet), 1866 Henri Fantin-Latour: A Studio in the Batingnolles, 1870 Claude Monet: The Thames below Westminster, c. -

The Barbizon School of Painters Were Part of an Art Movement Towards Realism in Art, Which Arose in the Context of the Dominant Romantic Movement of the Time

Barbizon School The Barbizon school of painters were part of an art movement towards Realism in art, which arose in the context of the dominant Romantic Movement of the time. The Barbizon school was active roughly from 1830 until 1870. It takes its name from the village of Barbizon, France, near the Forest of Fontainebleau, where many of the artists gathered. Some of the most prominent features of this school are its tonal qualities, colour, loose brushwork, and softness of form. In 1824 the Salon de Paris exhibited works of John Constable. His rural scenes influenced some of the younger artists of the time, moving them to abandon formalism and to draw inspiration directly from nature. Natural scenes became the subjects of their paintings rather than mere backdrops to dramatic events. During the Revolutions of 1848 artists gathered at Barbizon to follow Constable's ideas, making nature the subject of their paintings. The French landscape became a major theme of the Barbizon painters. The leaders of the Barbizon school were Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, and Charles-François Daubigny. Rousseau, Thunderstorms mood in the level of Montmartre 1845-48 Rousseau, Avenue of Chestnut Treees Rousseau, Avenue of Chestnut Treees 1837 watercolour Théodore Rousseau (1812 – 1867) was born in Paris, France in a bourgeois family. Although at first his father regretted his decision to persue a carreer as an artist he became reconciled to his son forsaking business, and throughout the artist's career (for he survived his son) was a sympathizer with him in all his conflicts with the Paris Salon authorities. -

Jean Francois Millet

Jean Francois Millet Estelle M. Hurll The Project Gutenberg eBook, Jean Francois Millet, by Estelle M. Hurll This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Jean Francois Millet Author: Estelle M. Hurll Release Date: August 5, 2004 [eBook #13119] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-646-US (US-ASCII) ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JEAN FRANCOIS MILLET*** E-text prepared by Juliet Sutherland, Leah Moser, and the Project Gutenberg Online Distributed Proofreading Team Note: Project Gutenberg also has an HTML version of this file which includes the original illustrations. See 13119-h.htm or 13119-h.zip: (http://www.gutenberg.net/1/3/1/1/13119/13119-h/13119-h.htm) or (http://www.gutenberg.net/1/3/1/1/13119/13119-h.zip) JEAN FRANCOIS MILLET A Collection of Fifteen Pictures and a Portrait of the Painter, with Introduction and Interpretation by ESTELLE M. HURLL The Riverside Art Series 1900 Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. [Illustration: JEAN FRANCOIS MILLET] PREFACE In making a selection of Millet's pictures, devoted as they are to the single theme of French peasant life, variety of subject can be obtained only by showing as many phases of that life as possible. Our illustrations therefore represent both men and women working separately in the tasks peculiar to each, and working together in the labors shared between them. -

Van Gogh, Nature, and Spirituality

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Art and Art History Honors in the Major Theses Spring 2021 Van Gogh, Nature, and Spirituality Emma Krall [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.rollins.edu/honors-in-the-major-art Recommended Citation Krall, Emma, "Van Gogh, Nature, and Spirituality" (2021). Art and Art History. 2. https://scholarship.rollins.edu/honors-in-the-major-art/2 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors in the Major Theses at Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Art History by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VAN GOGH, NATURE, AND SPIRITUALITY APRIL 1, 2021 EMMA KRALL Honors in the Major Thesis Advisor- Dr. Susan Libby 1 Table of Contents List of Figures ................................................................................................ 2 Introduction .................................................................................................... 3 Chapter 1- Religion and Family ..................................................................... 7 Chapter 2- The Beginnings of Life as An Artist .......................................... 13 Chapter 3- Turning Towards Nature ............................................................ 21 Chapter 4- Wheat Fields ............................................................................... 26 Chapter 5- Millet and The Sower ................................................................. -

CLASS and SOCIETY

CLASS and SOCIETY: NINETEENTH-CENTURY FRENCH REALISM: FOCUS (Honoré Daumier and Gustave Courbet) CLASS and SOCIETY: NINETEENTH-CENTURY FRENCH REALISM: SELECTED TEXT (Honoré Daumier and Gustave Courbet) REALISM: GUSTAVE COURBET and HONORE DAUMIER Online Links: Gustave Courbet – Wikipedia Courbet's Burial at Ornans – Smarthistory The Stonebreakers – Smarthistory Why Gustave Courbet Still has the Power to Shock - The Independent Honore Daumier – Wikipedia Courbet's The Artist's Studio - Smarthistory Aestheticism versus Realism The concept of “art for art’s sake”, without any moral, social, political or any other didactic purpose, was at the center of much 19th century thought though as often attacked as commended. Its origin can be traced by to Immanuel Kant who, in his Critique of Judgment of 1790, broke with traditional aesthetics by analyzing the previously unified notions of the good, the tree and the beautiful as discrete categories. Appreciation of beauty is, he argued, subjective and disinterested – unaffected by an object’s purpose. Gustave Courbet. The Stone Breakers, 1849 , oil on canvas (destroyed) Realism was an artistic movement that began in France in the 1850s, after the 1848 Revolution. Realists rejected Romanticism, which had dominated French literature and art since the late 18th century. Realism revolted against the exotic subject matter and exaggerated emotionalism and drama of the Romantic movement. Instead it sought to portray real and typical contemporary people and situations with truth and accuracy, and not avoiding unpleasant or sordid aspects of life. Realist works depicted people of all classes in situations that arise in ordinary life, and often reflected the changes wrought by the Industrial Revolution. -

The Shapes Arise: Realism

ART HISTORY Journey Through a Thousand Years “The Shapes Arise” Week Eleven: Realism The Aesthetic Movement - William Holman Hunt, The Lady of Shalott – The Wonderful World of Whistler – Harmony in Blue and Gold - Early Photography: Niépce, Talbot and Muybridge - Early Photography: Making Daguerreotypes A Beginner’s Guide to Realism - Gustave Courbet, The Stonebreakers – Rosa Bonheur, Sheep in the Highlands - “Jean-Francois Millet, A Poem” – Life of Jean-Francois Millet – The Angelus - William Powell Frith, Derby Day Konstantin Savitsky: Repair work on the railway, 1874, Tretyakov Gallery The Romantic movement in art transformed as the nineteenth century went on – it took new form in the Aesthetic Movement. John William Waterhouse: Windflowers , Dr. Rebecca Jeffrey Easby, "The Aesthetic Movement" From smARThistory (2016) Art for the sake of art The Aesthetic Movement, also known as “art for art’s sake,” permeated British culture during the latter part of the 19th century, as well as spreading to other countries such as the United States. Based on the idea that beauty was the most important element in life, writers, artists and designers sought to create works that were admired simply for their beauty rather than any narrative or moral function. This was, of course, a slap in the face to the tradition of art, which held that art needed to teach a lesson or provide a morally uplifting message. The movement blossomed into a cult devoted to the creation of beauty in all avenues of life from art and literature, to home decorating, to fashion, and embracing a new simplicity of style. “The Six-Mark Tea-Pot” in Punch, October 30, 1880 (caption reads: Aesthetic Bridegroom. -

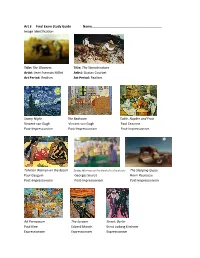

Art 3 Final Exam Study Guide Name______Image Identification

Art 3 Final Exam Study Guide Name_______________________________________ Image Identification Title: The Gleaners Title: The Stonebreakers Artist: Jean Francois Millet Artist: Gustav Courbet Art Period: Realism Art Period: Realism Starry Night The Bedroom Table, Napkin and Fruit Vincent van Gogh Vincent van Gogh Paul Cezanne Post-Impressionism Post-Impressionism Post-Impressionism Tahitian Women on the Beach Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grand Jatte The Sleeping Gypsy Paul Gauguin Georges Seurat Henri Rousseau Post-Impressionism Post-Impressionism Post-Impressionism Ad Parnassum The Scream Street, Berlin Paul Klee Edvard Munch Ernst Ludwig Kirchner Expressionism Expressionism Expressionism Yellow Cow Composition VIII Franz Marc Wassily Kandinsky Expressionism Expressionism Factory, Horta de Ebbo Violin and Jug Weeping Woman Pablo Picasso Georges Braque Pablo Picasso Cubism Cubism Cubism The Son of Man The Persistence of Memory Metamorphosis of Narcissus Rene Magritte Salvador Dali Salvador Dali Surrealism Surrealism Surrealism The Red Tower Giorgio de Chirico Surrealism Campbell’s Soup Cans Twenty-five Colored Marilyns Queen Elizabeth II Andy Warhol Andy Warhol Andy Warhol Pop Art Pop Art Pop Art Drowning Girl Hopeless Varoom Roy Lichtenstein Roy Lichtenstein Roy Lichtenstein Pop Art Pop Art Pop Art Clothespin Flag Retroactive I Claes Oldenburg Jasper Johns Robert Rauschenberg Pop Art Pop Art Pop Art Characteristics of Post-Impressionism -symbolic personal images -abstract form -application of paint in organized pattern (Van Gogh/Seurat) Characteristics of Expressionism - Has emotional character - Drew inspiration from ‘primitive art’ - Was associated with Northern Europe 3 things that influenced Expressionism - Fauvism, African art, German Gothic art Expressionism is mostly associated with Germany. The TWO main groups of German Expressionism were Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) and Die Brucke (The Bridge) - Cubism focused on 2 main things: 1. -

Modernization and Rural Imagery at the Paris Salon: an Interdisciplinary Approach to the Economic History of Art

Modernization and Rural Imagery at the Paris Salon: An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Economic History of Art Diana Seave Greenwald Self-Archived Version, DO NOT CITE For full copy-edited version see: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/ehr.12695 1 Modernization and Rural Imagery at the Paris Salon: An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Economic History of Art I. “Behind the three gleaners one sees, vaguely silhouetted on the leaded horizon, the pikes of the popular riots and scaffolding of [17]93.”1 “Millet’s gleaners—ugly, old, dirty, dusty—give birth to a classic idea of beauty that does not come from any nymph ... With elements so simple, means so sober, and resources so restrained, the artist has created one of the most serious canvases at the Salon.”2 “Millet sculpts [misery] on canvas with somewhat pedantic proficiency. Like his gleaners, from the previous Salon, Woman Grazing a Cow has gigantic pretensions.”3 These quotes each describe or reference the same painting, Jean-François Millet’s (1814– 75) The Gleaners (1857) (fig. 1). In the same work, one critic sees the threat of revolution, one sees beauty in ugliness, and the other sees pretentiousness. The painting depicts a lavender and powder blue sky shining over a golden wheat field; hay stacks, cows, and a small village lie on the horizon. Three large female figures dominate this Georgic landscape. They collect the bits of wheat that reapers have left behind after the harvest. Hunched and clad in rough clothing, none of their heavy-boned bodies breaks the horizon line. -

Gardner's Art Through the Ages

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood 1 JOHN EVERETT MILLAIS, Ophelia, 1852. Oil on canvas, 2’ 6” x 3’ 8”. 2 Tate Gallery, London. DANTE GABRIEL ROSSETTI, Beata Beatrix, ca. 1863. Oil on canvas, 2’ 10” x 2’ 2”. Tate Gallery, London. 3 Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood occurred simultaneously as Realism in the _____________.1850’s This movement focused on fanciful, _____________________fictional and historical imagery. It was often based on literary works and featured _____________________idealized human forms. High level of detail in scenery was, however, achieved through ______________________observation and close studies. Artists from this movement did not want to be limited to contemporary scenes or social commentary like the Realist artists. • • How is the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood different from the Realism movement? Realism 5 GUSTAVE COURBET, The Stone Breakers, 1849. Oil on canvas, 5’ 3” x 8’ 6”. Formerly at Gemäldegalerie, 6 Dresden (destroyed in 1945). GUSTAVE COURBET, Burial at Ornans, 1849. Oil on canvas, approx. 10’ x 22’. Louvre, Paris. 7 JEAN-FRANÇOIS MILLET, The Gleaners, 1857. Oil on canvas, approx. 2’ 9” x 3’ 8”. Louvre, Paris. 8 HONORÉ DAUMIER, The Third-Class Carriage, ca. 1862. Oil on canvas, 2’ 1 3/4” x 2’ 11 1/2”. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 9 ÉDOUARD MANET, Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (Luncheon on the Grass), 10 1863. Oil on canvas, approx. 7’ x 8’ 10”. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. ÉDOUARD MANET, Olympia, 1863. Oil on canvas, 11 4’ 3” x 6’ 3”. Musée d’Orsay, Paris. WINSLOW HOMER, The Veteran in a New Field, 1865. Oil on canvas, 2’ 1/8” x 3’ 2 1/8”. -

Contents a Picture Paints a Thousand Words

Contents A Picture Paints a Thousand Words ......................................................................................4 Vinny Van Gogh ......................................................................................................................6 Activities: Art Soundtrack and Circles and Swirls ................................................................................................9 Reproducible Fact Sheet .....................................................................................................................................10 The Dream-world of Dalí ......................................................................................................11 Activities: Dream Collage and Surreal Stories ....................................................................................................14 Reproducible Fact Sheet .....................................................................................................................................15 The Ever-Changing Gardens of Monet ...............................................................................16 Activities: The Seasons and Put Yourself in the Picture .....................................................................................19 Reproducible Fact Sheet .....................................................................................................................................20 Yo, Leonardo! ........................................................................................................................1 -

Rethinking Copyrights: the Effect of Imitation on Cultural Creativity and Diversity

No citation is allowed without authors’ permission. Rethinking Copyrights: The Effect of Imitation on Cultural Creativity and Diversity Jimmyn Parc Seoul National University & Sciences Po Paris March 7 2018 The Gran Madre di Dio or Great Mother of God in Turin, Italy is a neoclassic-style church that was inaugurated in 1834 to commemorate the return of the King Victor Emmanuel I of Sardinia to the throne after the defeat of Napoleon. This church features a dome as can be seen in Figure 1. On the inner part of the dome, many rosettes were engraved in stone which can be easily viewed from inside the church. Each rosette is different from one another (see the right image in Figure 1). Most tour guides as well as local Turinians will explain that each of them has been crafted differently on purpose for ornamental reasons. Knowing that carving the same object on stone was much harder in the past, it would be more rational to assume that the dissimilarity of each rosette was due to a lack of technology, rather than a process of ornamentalization. Notes: Gran Madre di Dio (left top); cross section diagram (left down); dome (right). Sources: Tripadvisor (left top); Museo Torino (left bottom); Vanupied, Photo by Gianni Caeddu (right). Figure 1. Rosettes under Dome (Gran Madre di Dio, Turin, Italy) In fact, this way of ornament decoration where each item is unique and different can be found in other places across Europe as well as in Asia. For example, often thousands of small Buddha 1 No citation is allowed without authors’ permission. -

JEAN FRANCOIS MILLET a Collection of Fifteen Pictures and A

JEAN FRANCOIS MILLET A Collection of Fifteen Pictures and a Portrait of the Painter, with Introduction and Interpretation by ESTELLE M. HURLL The Riverside Art Series 1900 [Illustration: JEAN FRANCOIS MILLET] PREFACE In making a selection of Millet's pictures, devoted as they are to the single theme of French peasant life, variety of subject can be obtained only by showing as many phases of that life as possible. Our illustrations therefore represent both men and women working page 1 / 84 separately in the tasks peculiar to each, and working together in the labors shared between them. There are in addition a few pictures of child life. The selections include a study of the field, the dooryard, and the home interior, and range from the happiest to the most sombre subjects. They show also considerable variety in artistic motive and composition, and taken together fairly represent the scope of Millet's work. ESTELLE M. HURLL. NEW BEDFORD, MASS. March, 1900. CONTENTS AND LIST OF PICTURES PORTRAIT OF MILLET. DRAWN BY HIMSELF INTRODUCTION I. ON MILLET'S CHARACTER AS AN ARTIST II. ON BOOKS OF REFERENCE III. HISTORICAL DIRECTORY OF THE PICTURES OF THIS COLLECTION page 2 / 84 IV. OUTLINE TABLE OF THE PRINCIPAL EVENTS IN MILLET'S LIFE V. SOME OF MILLET'S ASSOCIATES I. GOING TO WORK II. THE KNITTING LESSON III. THE POTATO PLANTERS IV. THE WOMAN SEWING BY LAMPLIGHT V. THE SHEPHERDESS VI. THE WOMAN FEEDING HENS VII. THE ANGELUS VIII. FILLING THE WATER-BOTTLES IX. FEEDING HER BIRDS page 3 / 84 X. THE CHURCH AT GREVILLE XI.