ENGLISH LITERATURE B a /AS Level for AQA Teacher’S Resource A/AS Level English Literature B for AQA Teacher’S Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning Was a Romantic Poet in Great Effect When Disclosing a Macabre Or Every Sense of the Word

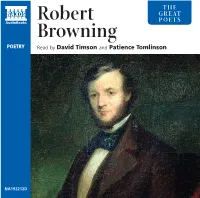

THE GREAT Robert POETS Browning POETRY Read by David Timson and Patience Tomlinson NA192212D 1 How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix 3:49 2 Life in a Love 1:11 3 A Light Woman 3:42 4 The Statue and the Bust 15:16 5 My Last Duchess 3:53 6 The Confessional 4:59 7 A Grammarian’s Funeral 8:09 8 The Pied Piper of Hamelin 7:24 9 ‘You should have heard the Hamelin people…’ 8:22 10 The Lost Leader 2:24 11 Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister 3:55 12 The Laboratory 3:40 13 Porphyria’s Lover 3:47 14 Evelyn Hope 3:49 15 Home Thoughts from Abroad 1:19 16 Pippa’s Song 0:32 Total time: 76:20 = David Timson = Patience Tomlinson 2 Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning was a romantic poet in great effect when disclosing a macabre or every sense of the word. He was an ardent evil narrative, as in The Laboratory, or The lover who wooed the poet Elizabeth Confessional or Porphyria’s Lover. Barrett despite fierce opposition from Sometimes Browning uses this matter- her tyrannical father, while as a poet – of-fact approach to reduce a momentous inheriting the mantle of Wordsworth, occasion to the colloquial – in The Keats and Shelley – he sought to show, Grammarian’s Funeral, for instance, in in the Romantic tradition, man’s struggle which a scholar has spent his life pursuing with his own nature and the will of God. knowledge at the expense of actually But Browning was no mere imitator of enjoying life itself. -

The Victorian Newsletter

The Victorian Newsletter Deborah A. Logan, Editor Western Kentucky University Tables of Contents, #111 (2007) through #1 (1952) The Victorian Newsletter Number 111 Spring 2007 Contents Page Carlyle's Influence on Shakespeare 1 by Robert Sawyer Imagining Ophelia in Christina Rossetti's ''Sleeping at Last'' 8 by Mary Faraci The Poison Within: Robert Browning' s ''The Laboratory'' 10 by David Sonstroem ''Her life was in her books'': Jean lngelow in the Literary Marketplace 12 by Maura Ives The Buddhist Sub-Text and the Imperial Soul-Making in Kim 20 by Young Hee Kwon ''Gliding'': A Note On the Exquisite Delicacy of the Religious Glissade Motif in Hopkins's ''The Windhover'' 29 by Nathan Cervo Coming in The Victorian Newsletter 29 Books Received 30 Notice 32 The Victorian Newsletter Number 110 Fall 2006 Contents Page Reading Hodge: Preserving Rural Epistemologies in Hardy's Far from the Madding Crowd 1 by Eric G. Lorentzen Unmanned by Marriage and the Metropolis in Gissing's The Whirlpool 10 by Andrew Radford Anthony Trollope's Lady Anna and Shakespeare's Othello 18 by Maurice Hunt The Romantic and the Familiar: Third-Person Narrative in Chapter 11 of Bleak House 23 by David Paroissien Tennyson's In Memoriam, Section 123, and the Submarine Forest on the Lincolnshire Coast 28 by Patrick Scott Coming in Victorian Newsletter 30 Books Received 31 The Victorian Newsletter Number 109 Spring 2006 Contents Page Scandalous Sensations: The Woman In White on the Victorian Stage 1 by Maria K. Bachman Nostalgia to Amnesia: Charles Dickens, Marcus Clarke and Narratives of Australia’s Convict Origins 9 by Beth A. -

English Literature - Poetry Anthology

CCEA GCSE English Literature - Poetry Anthology Poetry Anthology GCSE ENGLISH LITERATURE For use with the Specification for first teaching from Autumn 2017 and first examination in Summer 2018 Issued: August 2017 Poetry Anthology For use with the Specification for first teaching from Autumn 2017 and first examination in Summer 2018 Issued: August 2017 English 1 Literature CCEA GCSE English Literature - Poetry Anthology 2 CCEA GCSE English Literature - Poetry Anthology Contents Page Anthology One: IDENTITY 5 Anthology Two: RELATIONSHIPS 23 Anthology Three: CONFLICT 37 3 CCEA GCSE English Literature - Poetry Anthology 4 CCEA GCSE English Literature - Poetry Anthology Anthology One: IDENTITY 5 CCEA GCSE English Literature - Poetry Anthology SONNET 29 When, in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes, I all alone beweep my outcast state, And trouble deaf heaven with my bootless cries, And look upon myself and curse my fate, Wishing me like to one more rich in hope, Featured like him, like him with friends possessed, Desiring this man’s art and that man’s scope, With what I most enjoy contented least: Yet in these thoughts myself almost despising, Haply I think on thee, and then my state, Like to the lark at break of day arising From sullen earth, sings hymns at heaven’s gate; For thy sweet love remembered such wealth brings That then I scorn to change my state with kings. William Shakespeare 6 CCEA GCSE English Literature - Poetry Anthology DOVER BEACH The sea is calm to-night, The tide is full, the moon lies fair Upon the Straits;―on the French coast, the light Gleams, and is gone; the cliffs of England stand, Glimmering and vast, out in the tranquil bay. -

Gcse English and English Literature

GCSE ENGLISH AND ENGLISH LITERATURE INFORMATION AND PERSONAL PROFILE FOR STUDENTS AT ASHTON COMMUNITY SCIENCE COLLEGE NAME: ………………………………………….. TEACHER: ……………………………………. 1 THE COURSE(S) You will be following the AQA, Specification A syllabus for English . As an additional GCSE, many of you will be following the AQA, Specification A syllabus for English Literature . (www.aqa.org.uk) There are two methods of assessment within each course: 1. Coursework 2. Examination The following tables give you a breakdown of the elements that need to be studied and the work that needs to be completed in each area. The percentage weighting of each element in relation to your overall grade is also included: Coursework Written If you are entered for English and English Literature you will complete five written assignments. If you are entered for English only you will complete four written assignments: ASSIGNMENT EXAMPLE TASKS % OF OVERALL GCSE Original Writing A short story or an 5 % of the English GCSE (Writing assessment for autobiographical piece of English only) writing. Media A close analysis of an 5% of the English GCSE (Writing assessment for advertising campaign or of the English only) marketing for a film. Shakespeare A close analysis of the impact 5% of the English GCSE plus (Reading assessment for created by the first 95 lines in 10% of the English Literature English and English Lit.) Romeo and Juliet. GCSE Pre-Twentieth Century Prose A comparison between two 5% of the English GCSE plus Study chapters in Great Expectations 10% of the English Literature (Reading assessment for by Charles Dickens. GCSE English and English Lit.) Twentieth Century Play A close analysis of the role 10% of the English Literature (Assessment for English played by the narrator in Blood GCSE Literature only) Brothers by Willy Russell Spoken 2 In addition to written coursework there is also a spoken coursework element for English GCSE. -

Theodora Michaeliodu Laura Pence Jonathan Tweedy John Walsh

Look, the world tempts our eye, And we would know it all! Setting is a basic characteristic of literature. Novels, short stories, classical Greece and medieval Europe and the literary traditions the temporal and spatial settings of individual literary works, one can dramas, film, and much poetry—especially narrative poetry—typically inspired by those periods. Major Victorian poets, including Tennyson, map and visualize the distribution of literary settings across historical We map the starry sky, have an identifiable setting in both time and space. Victorian poet the Brownings, Arnold, Rossetti, and Swinburne, provide a rich variety periods and geographic space; compare these data to other information, We mine this earthen ball, Matthew Arnold’s “Empedocles on Etna,” for instance, is set in Greek of representations of classical and medieval worlds. But what does the such as year of publication or composition; and visualize networks of We measure the sea-tides, we number the sea-sands; Sicily in the fifth century B.C. “Empedocles” was published in 1852. quantifiable literary data reveal about these phenomena? Of the total authors and works sharing common settings. The data set is a growing Swinburne’s Tristram of Lyonesse (1882) is set in Ireland, Cornwall, number of published works or lines of verse from any given period, collection of work titles, dates, date ranges, and geographic identifiers We scrutinise the dates and Brittany, but in an uncertain legendary medieval chronology. or among a defined set of authors or texts, how many texts have and coordinates. Challenges include settings of imprecise, legendary, Of long-past human things, In the absence of a narrative setting, many poems are situated classical, medieval, biblical, or contemporary settings? How many texts and fictional time and place. -

Peculiaris Lepores: Grotesque As Moment in British Literature 1Sambhunath Maji, 2Dr

American International Journal of Available online at http://www.iasir.net Research in Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences ISSN (Print): 2328-3734, ISSN (Online): 2328-3696, ISSN (CD-ROM): 2328-3688 AIJRHASS is a refereed, indexed, peer-reviewed, multidisciplinary and open access journal published by International Association of Scientific Innovation and Research (IASIR), USA (An Association Unifying the Sciences, Engineering, and Applied Research) Peculiaris Lepores: Grotesque as Moment in British Literature 1Sambhunath Maji, 2Dr. Birbal Saha 1Assistant Professor, 2Associate Professor & HOD 1Department of English, 2Department of Education, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, Purulia P.O- Sainik School, Dist.- Purulia, West Bengal Abstract: Beauty has its countless faces to delineate itself. The most familiar face of beauty, in its presenta- tion in literature, is reliable, consistent and coherent. Aquinas defined beauty as visa placenta (‘the sight that pleases us is beautiful’). Joyce’s Dedalus envisioned another version of beauty. The gratification of beauty, says he, all depends on the organ with one perceives it. The other face of beauty is very queer and strange. It is, to some extent, misleading and vague. Alexander Pope used a weird appellation (‘aweful beauty’) to sum up Belinda’s grace. In Easter 1916 Yeats had more substantiate view of beauty, which orig- inated from the forfeit of Irish patriots: “All that changed, utterly changed, a terrible born”. This indistinct and blurred face of beauty can justly be comprehended as something, -

GCSE English Literature a Foundation Question Paper June 2010

General Certificate of Secondary Education June 2010 English Literature 3712/F (Specification A) Foundation Tier F Tuesday 25 May 2010 9.00 am to 10.45 am For this paper you must have: ! a 12-page answer book ! an unannotated copy of the AQA Anthology labelled 2008 onwards which you have been studying ! an unannotated copy of the relevant post-1914 novel if you have been studying this instead of the Anthology short stories. Time allowed ! 1 hour 45 minutes Instructions ! Use black ink or black ball-point pen. ! Write the information required on the front of your answer book. The Examining Body for this paper is AQA. The Paper Reference is 3712/F. ! Answer two questions. ! Answer one question from Section A and one question from Section B. ! In your answer to a question from Section B, you must refer to pre-1914 and post-1914 poetry. ! This is an open text examination. You must have copies of texts in the examination room. The texts must not be annotated and must not contain additional notes or materials. ! Write your answers in the answer book provided. ! Do all rough work in your answer book. Cross through any work you do not want to be marked. ! You must not use a dictionary. Information ! The maximum mark for this paper is 66. ! There are 27 marks for Section A and 36 marks for Section B. You will be awarded up to three marks for Quality of Written Communication. ! The marks for questions are shown in brackets. ! You are reminded of the need for good English and clear presentation in your answers. -

An Examination of the Conclusions to Browning's Dramatic Monologues

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 3-1966 An Examination of The Conclusions to Browning's Dramatic Monologues Charlotte Hudgens Beck University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Beck, Charlotte Hudgens, "An Examination of The Conclusions to Browning's Dramatic Monologues. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 1966. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/2899 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Charlotte Hudgens Beck entitled "An Examination of The Conclusions to Browning's Dramatic Monologues." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in English. Kenneth Knickerbocker, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: F. DeWolfe Miller, Norman Sanders Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) March 1, 19 66 To th e Graduate Council: I am su bmitting herewith a th esis wr i tten by Char l otte Hud gen s Beck en ti tl ed ·�n Examination of the Conclusions to Browning's Dra matic Monol ogues." I recommend th at it be accepted for nine quar ter hours of credit in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degr ee of Master of Arts, wi th a maj or in En gl ish. -

Gender Relations in Robert Browning's Dramatic Monologues

Ghent University Faculty Arts and Philosophy – English Literature Department Gender Relations in Robert Browning’s Dramatic Monologues FREYA MAENHOUT DISSERTATION SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF LICENCE IN GERMANIC PHILOLOGY Promotor: Prof. Dr. Marysa Demoor May 2007 Ghent University Faculty Arts and Philosophy – English Literature Department Gender Relations in Robert Browning’s Dramatic Monologues FREYA MAENHOUT DISSERTATION SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF LICENCE IN GERMANIC PHILOLOGY Promotor: Prof. Dr. Marysa Demoor May 2007 2 Acknowledgements First of all I would like to thank my promotor, Prof. Dr. Marysa Demoor, for her time and advice; Marianne Van Remoortel, for supplying me with additional information; the libraries of the English and Dutch department of Ghent University; the public library in Louvain; B.Brabant for his help; my proofreaders, C.Van Huele, C.Kelly, M.Repovž and L.Baldwin; and finally my parents for their support. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 5 2. ROBERT BROWNING AND THE DRAMATIC MONOLOGUE ............................. 7 A. His Life and Work ....................................................................................................................................... 7 B. The Dramatic Monologue .............................................................................................................................. 11 1. The Term ―Dramatic Monologue‖ ......................................................................................................... -

Robert Browning 1 Robert Browning

Robert Browning 1 Robert Browning Robert Browning Robert Browning during his later years Born 7 May 1812 Camberwell, London, England Died 12 December 1889 (aged 77) Venice, Italy Occupation Poet Notable work(s) The Ring and the Book, Men and Women, The Pied Piper of Hamelin, Porphyria's Lover, My Last Duchess Signature Robert Browning (7 May 1812 – 12 December 1889) was an English poet and playwright whose mastery of dramatic verse, especially dramatic monologues, made him one of the foremost Victorian poets. Early years Robert Browning was born in Camberwell - a district now forming part of the borough of Southwark in South London, England - the only son of Sarah Anna (née Wiedemann) and Robert Browning.[1][2] His father was a well-paid clerk for the Bank of England, earning about £150 per year.[3] Browning’s paternal grandfather was a wealthy slave owner in Saint Kitts, West Indies, but Browning's father was an abolitionist. Browning's father had been sent to the West Indies to work on a sugar plantation, but revolted by the slavery there, he returned to England. Browning’s mother was a daughter of a German shipowner who had settled in Dundee, and his Scottish wife. Browning had one sister, Sarianna. Browning's paternal grandmother, Margaret Tittle, who had inherited a plantation in St Kitts, was rumoured within the family to have had some Jamaican mixed race ancestry. Author Julia Markus suggests St Kitts rather than Jamaica.[4][5] There is little evidence to support this rumour, and it seems to be merely an anecdotal family story.[6] Robert's father, a literary collector, amassed a library of around 6,000 books, many of them rare. -

A Historical and Critical Study of Browning's Asolando Volume

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 3-1961 A Historical and Critical Study of Browning's Asolando Volume Paulina Estella Buhl University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Buhl, Paulina Estella, "A Historical and Critical Study of Browning's Asolando Volume. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1961. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2989 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Paulina Estella Buhl entitled "A Historical and Critical Study of Browning's Asolando Volume." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Kenneth L. Knickerbocker, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Alwin Thaler, Bain T. Stewart, Reinhold Nordsieck, LeRoy Graf Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) Copyl'ight by PAULINA ESTELLA BUHL 1961 March 2, 1961 To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Paulina Estella Buhl entitled 11A Historical and Critical Study of Browning's Asolando Volume ." I reconunend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the require ments for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. -

Seeing Trauma: the Known and the Hidden in Nineteenth-Century Literature Alisa M

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School April 2018 Seeing Trauma: The Known and the Hidden in Nineteenth-Century Literature Alisa M. DeBorde University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Scholar Commons Citation DeBorde, Alisa M., "Seeing Trauma: The Known and the Hidden in Nineteenth-Century Literature" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7141 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Seeing Trauma: The Known and Hidden in Nineteenth-Century Literature By Alisa M. DeBorde A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Marty Gould, Ph.D. Laura L. Runge, Ph.D. Susan Mooney, Ph.D. Brook Sadler, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 29, 2018 Keywords: trauma, nineteenth-century, shock, dissociation, memory Copyright © 2018, Alisa M. DeBorde DEDICATION To David, Mariva, Maximillian, Cosette, and Fantine ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS From my mother who required that each of her six children “bring a book” wherever our travels took us, to my father who patiently read my stories and essays and taught me to value the nuances of words, to my siblings who modeled a love of learning, I am thankful for an upbringing rich in words, stories, and books.