Teaching Guide to Tony Barnstone's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers

Guide to Ella Fitzgerald Papers NMAH.AC.0584 Reuben Jackson and Wendy Shay 2015 Archives Center, National Museum of American History P.O. Box 37012 Suite 1100, MRC 601 Washington, D.C. 20013-7012 [email protected] http://americanhistory.si.edu/archives Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Music Manuscripts and Sheet Music, 1919 - 1973................................... 5 Series 2: Photographs, 1939-1990........................................................................ 21 Series 3: Scripts, 1957-1981.................................................................................. 64 Series 4: Correspondence, 1960-1996................................................................. -

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

MELBOURNE the ORANGE TABBY Who Let the Cat out of the Bag?’ Page A7

‘ERNIE,’ INSIDE MELBOURNE THE ORANGE TABBY Who let the cat out of the bag?’ Page A7 Vol. 9, No. 5 Your Local News and Information Source • www.HometownNewsOL.com Friday, Aug. 24, 2012 Community City council chooses search calendar firm for new city manager Sat. 9-5 • Sun 9-4 FRIDAY, AUG. 24 Colin Baenziger and Associates of Wellington ranked firms in the Associates to help to help find a new city search, made their cases (With this coupon. Valid Aug. 25 & 26, 2012) • Recovery from code- manager this fall. for why they should be pendence: Co-Depen- select candidates In January, Melbourne the organization the city Cocoa National Guard Armory dents Anonymous of City Manager Jack of Melbourne chooses to 308 N. Fiske Blvd., Cocoa, FL 32924 Melbourne is a women- By Chris Fish Schluckebier announced search for the new city only group. It is a twelve [email protected] his plans to retire after manager. 352-359-0134 or visit step fellowship of women providing a decade of “What we offer, basical- www.GunTraderGunShows.com whose common purpose MELBOURNE — In a service to residents of ly, is to bring you the best is recovery from codepen- unanimous vote held on Melbourne. people,” said Colin Baen- 031256 dence and the develop- Tuesday, Aug. 14, the Mel- At the Tuesday night ziger, owner of Colin ment and maintenance of bourne City Council fin- meeting, Colin Baenziger Baeziger and Associates, healthy relationships. Fiske Guide ished its executive search and Associates and Slavin to members of the coun- The CoDA of Melbourne firm selection, picking Management and Con- (women only) meeting is Colin Baenziger and sultants, the top two See FIRM, A5 includes Florida Tech on Fridays at 7 p.m. -

Family Law Section Commentator

The Florida Bar FAMILY LAW SECTION COMMENTATOR Spring 2019 Anya Cintron Stern, Esq. – Co-Editor Volume 1, No. 2 Anastasia Garcia, Esq. – Co-Editor The Commentator is prepared and published by the Family Law Section of The Florida Bar ABIGAIL BEEBE, WEST PALM BEACH – Chair AMY C. HAMLIN, ALTAMONTE SPRINGS – Chair-Elect DOUGLAS A. GREENBAUM, FORT LAUDERDALE – Treasurer HEATHER L. APICELLA, BOCA RATON – Secretary NICOLE L. GOETZ – Immediate Past Chair LAURA DAVIS SMITH, CORAL GABLES and SONJA JEAN, CORAL GABLES – Publications Committee Co-Chairs WILLE MAE SHEPHERD, TALLAHASSEE — Administrator DONNA RICHARDSON, TALLAHASSEE — Design & Layout Statements of opinion or comments appearing herein are those of the authors and contributors and not of The Florida Bar or the Family Law Section. Articles and cover photos to be considered for publication may be submitted to Anya Cintron Stern, Esq. ([email protected]), or Anastasia Garcia, Esq. ([email protected]), Co-Chairs of the Commentator. MS Word format is preferred for documents, and jpeg images for photos. ON THE COVER: Photograph courtesy Heather Apicella INSIDE THIS ISSUE 3 Message from the Chair 17 Addicition and Its Impact on Our Cases and Our Profession: First Article of Three 6 Comments from the Co-Chairs of the Publications Committee 21 Navigating Turbulent Waters: Dealing with Domestic Violence in a Divorce 7 Message from the Co-Chairs of the Commentator 26 Family Law Section In-State Retreat (Photos) 7 Section Calendar 31 Crafting Developmentally Appropriate Parenting Plans for Infants and Toddlers 8 Guest Editor's Corner 36 Psychosexual Evaluations in Family Law 11 Stress in Family Law Practice-Is There A Better Way For Families and 47 Shifting Gears: Making The Most of Life’s Practitioners Not-So-Little Changes Family Law Commentator 2 Spring 2019 Message from the Chair Abigail M. -

When I Open My Eyes, I'm Floating in the Air in an Inky, Black Void. the Air Feels Cold to the Touch, My Body Shivering As I Instinctively Hugged Myself

When I open my eyes, I'm floating in the air in an inky, black void. The air feels cold to the touch, my body shivering as I instinctively hugged myself. My first thought was that this was an awfully vivid nightmare and that someone must have left the AC on overnight. I was more than a little alarmed when I wasn't quite waking up, and that pinching myself had about the same amount of pain as it would if I did it normally. A single star twinkled into existence in the empty void, far and away from reach. Then another. And another. Soon, the emptiness was full of shining stars, and I found myself staring in wonder. I had momentarily forgotten about the biting cold at this breath-taking sight before a wooden door slammed itself into my face, making me fall over and land on a tile ground. I'm pretty sure that wasn't there before. Also, OW. Standing up and not having much better to do, I opened the door. Inside was a room with several televisions stacked on top of each other, with a short figure wrapped in a blanket playing on an old NES while seven different games played out on the screen. They turned around and looked at me, blinking twice with a piece of pocky in their mouth. I stared at her. She stared back at me. Then she picked up a controller laying on the floor and offered it to me. "Want to play?" "So you've been here all alone?" I asked, staring at her in confusion, holding the controller as I sat nearby. -

Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning Was a Romantic Poet in Great Effect When Disclosing a Macabre Or Every Sense of the Word

THE GREAT Robert POETS Browning POETRY Read by David Timson and Patience Tomlinson NA192212D 1 How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix 3:49 2 Life in a Love 1:11 3 A Light Woman 3:42 4 The Statue and the Bust 15:16 5 My Last Duchess 3:53 6 The Confessional 4:59 7 A Grammarian’s Funeral 8:09 8 The Pied Piper of Hamelin 7:24 9 ‘You should have heard the Hamelin people…’ 8:22 10 The Lost Leader 2:24 11 Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister 3:55 12 The Laboratory 3:40 13 Porphyria’s Lover 3:47 14 Evelyn Hope 3:49 15 Home Thoughts from Abroad 1:19 16 Pippa’s Song 0:32 Total time: 76:20 = David Timson = Patience Tomlinson 2 Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning was a romantic poet in great effect when disclosing a macabre or every sense of the word. He was an ardent evil narrative, as in The Laboratory, or The lover who wooed the poet Elizabeth Confessional or Porphyria’s Lover. Barrett despite fierce opposition from Sometimes Browning uses this matter- her tyrannical father, while as a poet – of-fact approach to reduce a momentous inheriting the mantle of Wordsworth, occasion to the colloquial – in The Keats and Shelley – he sought to show, Grammarian’s Funeral, for instance, in in the Romantic tradition, man’s struggle which a scholar has spent his life pursuing with his own nature and the will of God. knowledge at the expense of actually But Browning was no mere imitator of enjoying life itself. -

Pritchett K.D

Pritchett k.d. lang Volume 4, Number 1, January 5, 1994 FREE PHOTO: JEFF HELBERG Why the -.;:. legislator as the "yuppie ninjas" - have passed Chozen-ji Zen through the dojo's gates temple and martial to "talk story" with artsdojo in upper Tanouye, including the governor, a number of Kalihi Valley just legislators, at least one might be one of the Bishop Estate trustee, developer Herbert most important Horita, big-gun lawyer places you've never Wally Fujiyama, banking CEO Uonel Tokioka and a heard of couple of men known widely as behind-the scenes "arrangers." A couple of notorious underworld figures have also been known to go to Chozen-ji, and even the FBl's curiosity has appar ently been stirred by rumors of the dojo's powerconnections. From one perspective, it looks like a conspiracy theorist's dream. But f there's one thing this press. Chozen-ji is a Zen talk to a dojo follower town has a reputation Buddhist temple and and you'll get quite a dif.. Iforbesides mai tais somewhat exclusive cen ferent picture, one of an and hula girls, it's secre ter for the martial, fine angel network of tive power cliques that and healing arts headed dedicated people, as cut back-room deals far by locally born archbishop well intentioned as they from the public eye. The Tanouye Tenshin Roshi are connected, nurturing kinds of "hot spots" (roshiisan hope with the Story by where the influential con honorific title DEREK FERRAR guidance of gregate are many: the used for Tanouye. From golflinks, the Pacific heads of Zen temples), this perspective, the Club, reunions of the who teaches the samurai activities of the roshi 442nd Regiment, Vegas. -

EES PEKE MF-$3.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage

DOCUMENT RESUME ED'124 95 CS 202 789 English 591, 592, and 593--Advante Program: Images of - Man. INSTTUTIYN Jeffersrin County Board of EdLication, Louisvilke, Ky. PUB DATE 73 A NOTE . 117p. EES PEKE MF-$3.83 HC-$6.01 Plus Postage. DEJCEIPT9 Ameiican Literature; Composition Skills(Literary): *English Instruction; *Enqlish1LiteraturExpository Writing; *Gifted; Grade 12;.4q,ancipage Arts; *Lit,erature Appreciation; Secondary ducaltion 0/RSTFAc: For those students whq qualify, the Ad'ance Program. offers an opportunity to follow a stim atingitcurriculum desi4ned for the academically talented. The purposes f the course outlined in this guide for twelfth grade English ate- to brill4 the previous three years' studies in dvance Frogram 1nglish to -a-Meaningful c lmination; to c vide a chall ing, practical, college-level arse of study _hat includes t e traditionaltwelfth grade 'experiences in English?literat re; to expandhese experiences to /include represettatiyre liter-cure that offers a world view of the universality cf human exper ence; and to prepafe studentsadequaely' for advanced placement in co lege, The introductory unit onthe Fis'Iory of the English langue reinfrorces ninth and tenth grade linguistic studies and provide experieliceA'designed to bring the, stucents to a realization of t dynamic character of their /1 nguage--from Beowulf and Chau r to. Eliot and Shaw. The units 1 include exercises in expositor writing in correlation with the literature studies So that the studentcan discover their basic deficiencies and strengthen their skills. (JM) a. ******************************* Documents acquired by FR; includQ many informal anpubliShed *- * materials not avai ble from o her sources. ERIC makes every effort * . -

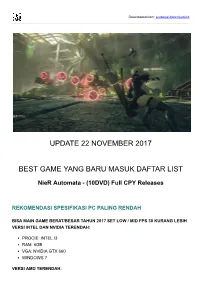

Update 22 November 2017 Best Game Yang Baru Masuk

Downloaded from: justpaste.it/premiumlink UPDATE 22 NOVEMBER 2017 BEST GAME YANG BARU MASUK DAFTAR LIST NieR Automata - (10DVD) Full CPY Releases REKOMENDASI SPESIFIKASI PC PALING RENDAH BISA MAIN GAME BERAT/BESAR TAHUN 2017 SET LOW / MID FPS 30 KURANG LEBIH VERSI INTEL DAN NVIDIA TERENDAH: PROCIE: INTEL I3 RAM: 6GB VGA: NVIDIA GTX 660 WINDOWS 7 VERSI AMD TERENDAH: PROCIE: AMD A6-7400K RAM: 6GB VGA: AMD R7 360 WINDOWS 7 REKOMENDASI SPESIFIKASI PC PALING STABIL FPS 40-+ SET HIGH / ULTRA: PROCIE INTEL I7 6700 / AMD RYZEN 7 1700 RAM 16GB DUAL CHANNEL / QUAD CHANNEL DDR3 / UP VGA NVIDIA GTX 1060 6GB / AMD RX 570 HARDDISK SEAGATE / WD, SATA 6GB/S 5400RPM / UP SSD OPERATING SYSTEM SANDISK / SAMSUNG MOTHERBOARD MSI / ASUS / GIGABYTE / ASROCK PSU 500W CORSAIR / ENERMAX WINDOWS 10 CEK SPESIFIKASI PC UNTUK GAME YANG ANDA INGIN MAINKAN http://www.game-debate.com/ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -------- LANGKAH COPY & INSTAL PALING LANCAR KLIK DI SINI Order game lain kirim email ke [email protected] dan akan kami berikan link menuju halaman pembelian game tersebut di Tokopedia / Kaskus ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -------- Download List Untuk di simpan Offline LINK DOWNLOAD TIDAK BISA DI BUKA ATAU ERROR, COBA LINK DOWNLOAD LAIN SEMUA SITUS DI BAWAH INI SUDAH DI VERIFIKASI DAN SUDAH SAYA COBA DOWNLOAD SENDIRI, ADALAH TEMPAT DOWNLOAD PALING MUDAH OPENLOAD.CO CLICKNUPLOAD.ORG FILECLOUD.IO SENDIT.CLOUD SENDSPACE.COM UPLOD.CC UPPIT.COM ZIPPYSHARE.COM DOWNACE.COM FILEBEBO.COM SOLIDFILES.COM TUSFILES.NET ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ -------- List Online: TEKAN CTR L+F UNTUK MENCARI JUDUL GAME EVOLUSI GRAFIK GAME DAN GAMEPLAY MENINGKAT MULAI TAHUN 2013 UNTUK MENCARI GAME TAHUN 2013 KE ATAS TEKAN CTRL+F KETIK 12 NOVEMBER 2013 1. -

COA Template

TM COMINGPresented by Council on Aging of West Floridaof AGE LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE FOR SENIORS SPRING 2013 An Exclusive Interview with Joan van Ark Hepatitis C Matters To Boomers Donating Your IRA Distributions Spring Herb Gardening www.ballingerpublishing.com www.coawfla.org COMMUNICATIONS CORNER Jeff Nall, APR, CPRC Editor-in-Chief The groundhog did not see his shadow and we’ve “sprung our clocks forward,” so now it is time to get out and enjoy the many outdoor activities that our area has to offer. Some of my favorites are the free outdoor concerts such as JazzFest, Christopher’s Concerts and Bands on the Beach. I tend to run into many of our readers at these events, but if you haven’t been, check out page 40. For another outdoor option for those with more of a green thumb, check out our article on page 15, which has useful tips for planting an herb garden. This issue also contains important information for baby boomers about Readers’ Services hepatitis C. According to the Centers for Disease Control, people born from Subscriptions Your subscription to Coming of Age 1945 through 1965 account for more than 75 percent of American adults comes automatically with your living with the disease and most do not know they have it. In terms of membership to Council on Aging of financial health, our finance article on page 18 explains how qualified West Florida. If you have questions about your subscription, call Jeff charitable distributions (QCDs) from Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) Nall at (850) 432-1475 ext. 130 or are attractive to some investors because QCDs can be used to satisfy required email [email protected]. -

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER

A History of English Literature MICHAEL ALEXANDER [p. iv] © Michael Alexander 2000 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W 1 P 0LP. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2000 by MACMILLAN PRESS LTD Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS and London Companies and representatives throughout the world ISBN 0-333-91397-3 hardcover ISBN 0-333-67226-7 paperback A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 O1 00 Typeset by Footnote Graphics, Warminster, Wilts Printed in Great Britain by Antony Rowe Ltd, Chippenham, Wilts [p. v] Contents Acknowledgements The harvest of literacy Preface Further reading Abbreviations 2 Middle English Literature: 1066-1500 Introduction The new writing Literary history Handwriting -

Penn National Freitag, 23

Penn National Freitag, 23. April 2021 Race 1 1 00:00 1200 m 16.400 Race 2 2 00:26 1600 m 11.800 Race 3 3 00:52 1670 m 10.800 Race 4 4 01:18 1200 m 18.100 Race 5 5 01:44 1200 m 19.000 Race 6 6 02:10 1200 m 31.600 Race 7 7 02:36 1670 m 28.000 Race 8 8 03:02 1600 m 10.800 Race 9 9 03:28 1600 m 15.400 Race 10 10 03:54 1200 m 11.800 Race 11 11 04:20 1200 m 10.000 23.04.2021 - Penn National ©2021 by Wettstar / LiveSports.at KG / Meeting ID: 231519 / ExtID: 205328 Seite 1 23.04.2021 - Penn National Rennen # 12 Seite 2 WANN STARTET IHR PFERD... All About Reyana 1 Eyes On Me 3 Jeanmillie Scorese 5 Our Nikki L 4 Start Cashin 6 Arctica 2 Favorite Doll 9 Jozani R V F 8 Paranoia 7 Stormy Spell 1 Athenasway 2 Foxy Hiya 2 Kinzea Stone 8 Patty Mac's Girl 11 Super Belle 4 Bay Of Angels 9 Gizmo's Princess 2 Lake Chicot 7 Pocopson Station 6 Tenerife Moon 9 Bearakontie 7 Gold Time Vixen 4 Life On The Edge 7 Prince Of Rain 6 Trending Up 5 Beautiful Success 11 Golden Celine 9 Literally 6 R Rajun Bull 5 Tribal Princess 10 Bess 7 Good Good 3 Mad Momma 1 Rose Ring 11 Triple A. Plus 5 Brynbella 9 Grace And Peace 11 Magalie 11 Secretive Revenge 10 Tweet Away Robin 7 Busch Latte 8 Great Bend 3 Main Cool Cat 3 Security Breach 3 Vouch 3 Cattle Drive 3 Guiltywithanexcuse 11 Mary Costa 11 Sexyama 1 Warfront Peace Rvf 1 Colonel Bailey 10 Happy Guy 8 Miss Josephine 10 Shacklefords Lady 11 Waverly Sunset 7 Come On Let's Ride 4 High Flying Guy 3 Motataabeq 5 Sleepy N Joyful 4 Who You Say I Am 5 Courting Jenny 1 Hitch Hiker 10 Musical Times 2 Smart Two A T 3 Wildcat Cura 6 Cowtown Tapit 8 Howsafearemycolors 4 Nearly Missed 2 Somerset Bay 6 Wind Ridge 8 Duke Of Hearts 8 Inhonorofthemoon 6 Not My Money 10 Spin Cycle 3 You Cant Catch Her 2 Emilia Strong 10 Jane 2 Offeryoucantrefuse 9 Spirit Or Spite 4 Zandora 11 WANN STARTET IHR JOCKEY / FAHRER..