Law Enforcement Driver Training Reference Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Law Section Commentator

The Florida Bar FAMILY LAW SECTION COMMENTATOR Spring 2019 Anya Cintron Stern, Esq. – Co-Editor Volume 1, No. 2 Anastasia Garcia, Esq. – Co-Editor The Commentator is prepared and published by the Family Law Section of The Florida Bar ABIGAIL BEEBE, WEST PALM BEACH – Chair AMY C. HAMLIN, ALTAMONTE SPRINGS – Chair-Elect DOUGLAS A. GREENBAUM, FORT LAUDERDALE – Treasurer HEATHER L. APICELLA, BOCA RATON – Secretary NICOLE L. GOETZ – Immediate Past Chair LAURA DAVIS SMITH, CORAL GABLES and SONJA JEAN, CORAL GABLES – Publications Committee Co-Chairs WILLE MAE SHEPHERD, TALLAHASSEE — Administrator DONNA RICHARDSON, TALLAHASSEE — Design & Layout Statements of opinion or comments appearing herein are those of the authors and contributors and not of The Florida Bar or the Family Law Section. Articles and cover photos to be considered for publication may be submitted to Anya Cintron Stern, Esq. ([email protected]), or Anastasia Garcia, Esq. ([email protected]), Co-Chairs of the Commentator. MS Word format is preferred for documents, and jpeg images for photos. ON THE COVER: Photograph courtesy Heather Apicella INSIDE THIS ISSUE 3 Message from the Chair 17 Addicition and Its Impact on Our Cases and Our Profession: First Article of Three 6 Comments from the Co-Chairs of the Publications Committee 21 Navigating Turbulent Waters: Dealing with Domestic Violence in a Divorce 7 Message from the Co-Chairs of the Commentator 26 Family Law Section In-State Retreat (Photos) 7 Section Calendar 31 Crafting Developmentally Appropriate Parenting Plans for Infants and Toddlers 8 Guest Editor's Corner 36 Psychosexual Evaluations in Family Law 11 Stress in Family Law Practice-Is There A Better Way For Families and 47 Shifting Gears: Making The Most of Life’s Practitioners Not-So-Little Changes Family Law Commentator 2 Spring 2019 Message from the Chair Abigail M. -

Pritchett K.D

Pritchett k.d. lang Volume 4, Number 1, January 5, 1994 FREE PHOTO: JEFF HELBERG Why the -.;:. legislator as the "yuppie ninjas" - have passed Chozen-ji Zen through the dojo's gates temple and martial to "talk story" with artsdojo in upper Tanouye, including the governor, a number of Kalihi Valley just legislators, at least one might be one of the Bishop Estate trustee, developer Herbert most important Horita, big-gun lawyer places you've never Wally Fujiyama, banking CEO Uonel Tokioka and a heard of couple of men known widely as behind-the scenes "arrangers." A couple of notorious underworld figures have also been known to go to Chozen-ji, and even the FBl's curiosity has appar ently been stirred by rumors of the dojo's powerconnections. From one perspective, it looks like a conspiracy theorist's dream. But f there's one thing this press. Chozen-ji is a Zen talk to a dojo follower town has a reputation Buddhist temple and and you'll get quite a dif.. Iforbesides mai tais somewhat exclusive cen ferent picture, one of an and hula girls, it's secre ter for the martial, fine angel network of tive power cliques that and healing arts headed dedicated people, as cut back-room deals far by locally born archbishop well intentioned as they from the public eye. The Tanouye Tenshin Roshi are connected, nurturing kinds of "hot spots" (roshiisan hope with the Story by where the influential con honorific title DEREK FERRAR guidance of gregate are many: the used for Tanouye. From golflinks, the Pacific heads of Zen temples), this perspective, the Club, reunions of the who teaches the samurai activities of the roshi 442nd Regiment, Vegas. -

COA Template

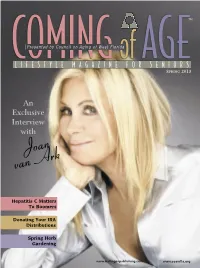

TM COMINGPresented by Council on Aging of West Floridaof AGE LIFESTYLE MAGAZINE FOR SENIORS SPRING 2013 An Exclusive Interview with Joan van Ark Hepatitis C Matters To Boomers Donating Your IRA Distributions Spring Herb Gardening www.ballingerpublishing.com www.coawfla.org COMMUNICATIONS CORNER Jeff Nall, APR, CPRC Editor-in-Chief The groundhog did not see his shadow and we’ve “sprung our clocks forward,” so now it is time to get out and enjoy the many outdoor activities that our area has to offer. Some of my favorites are the free outdoor concerts such as JazzFest, Christopher’s Concerts and Bands on the Beach. I tend to run into many of our readers at these events, but if you haven’t been, check out page 40. For another outdoor option for those with more of a green thumb, check out our article on page 15, which has useful tips for planting an herb garden. This issue also contains important information for baby boomers about Readers’ Services hepatitis C. According to the Centers for Disease Control, people born from Subscriptions Your subscription to Coming of Age 1945 through 1965 account for more than 75 percent of American adults comes automatically with your living with the disease and most do not know they have it. In terms of membership to Council on Aging of financial health, our finance article on page 18 explains how qualified West Florida. If you have questions about your subscription, call Jeff charitable distributions (QCDs) from Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) Nall at (850) 432-1475 ext. 130 or are attractive to some investors because QCDs can be used to satisfy required email [email protected]. -

May New Books

BROWNELL LIBRARY NEW TITLES, MAY 2018 FICTION F BALZAC Balzac, Honoré de, Old Goriot / Penguin Books,1951 Translation of: Pere Goriot. Focuses around the grasping Parisian society of the 1820s. F BARRY Barry, Sebastian, Days without end : a novel /Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC, 2017. Entering the U.S. army after fleeing the Great Famine in Ireland, seventeen-year-old Thomas McNulty and his brother-in-arms, John Cole, experience the harrowing realities of the Indian wars and the American Civil War between the Wyoming plains and Tennessee. F BOHJALIAN Bohjalian, Chris, The flight attendant : a novel /Doubleday, 2018 "From the New York Times bestselling author of The Guest Room, a powerful story about the ways an entire life can change in one night: A flight attendant wakes up in the wrong hotel, in the wrong bed, with a dead man - and no idea what happened. Cassandra Bowden is no stranger to hungover mornings. She's a binge drinker, her job with the airline making it easy to find adventure, and the occasional blackouts seem to be inevitable. She lives with them, and the accompanying self-loathing. When she awakes in a Dubai hotel room, she tries to piece the previous night back together, counting the minutes until she has to catch her crew shuttle to the airport."-- F BOWEN Bowen, Rhys, The Tuscan child /: Lake Union Publishing, 2018 “In 1944, British bomber pilot Hugo Langley parachuted from his stricken plane into the verdant fields of German-occupied Tuscany. Badly wounded, he found refuge in a ruined monastery and in the arms of Sofia Bartoli. -

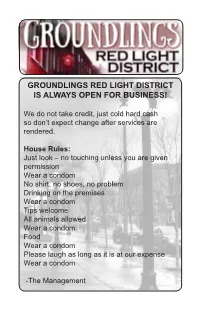

Groundlings Red Light District Is Always Open for Business!

GROUNDLINGS RED LIGHT DISTRICT IS ALWAYS OPEN FOR BUSINESS! We do not take credit, just cold hard cash so don’t expect change after services are rendered. House Rules: Just look – no touching unless you are given permission Wear a condom No shirt, no shoes, no problem Drinking on the premises Wear a condom Tips welcome All animals allowed Wear a condom Food Wear a condom Please laugh as long as it is at our expense Wear a condom -The Management KAREN MARUYAMA is having a blast directing the Main show again. She is a Main company alum who enjoys teaching here and at the American Film Institute. She also directs the acclaimed show The Black Version at the Largo Theater. She appeared in the films THE CAMPAIGN, THE BUCKET LIST and PULP FICTION. Her television credits include 2 BROKE GIRLS, ARRESTED DEVELOPMENT, NIP/TUCK, GHOST WHISPERER and has lent her voice to THE SIMPSONS, FUTURAMA, Karen AMERICAN DAD and FAMILY GUY. Maruyama (Director) Scott Beehner’s television appearances include CASUAL, EXTANT, NCIS, MODERN FAMILY, WORKAHOLICS, IT’S ALWAYS SUNNY IN PHILADELPHIA, HART OF DIXIE, SUPER FUN NIGHT, UP ALL NIGHT, PERFECT COUPLES, MAD LOVE, WORST WEEK, ZEKE & LUTHER, THUNDERMANS and THE YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS. Film credits include GANGSTER SQUAD, Woody Allen’s SWEET AND LOWDOWN, Whit Stillman’s THE LAST DAYS OF DISCO and TOMCATS. Originally from Omaha, Nebraska, Scott is a graduate of Scott Fordham University in New York City and the Actors Studio MFA Program. Beehner Timothy played Jack Flynn the head of GM on MAD MEN. -

A. the International Bill of Human Rights

A. THE INTERNATIONAL BILL OF HUMAN RIGHTS 1. Universal Declaration of Human Rights Adopted and proclaimed by General Assembly resolution 217 A (III) of 10 December 1948 PREAMBLE Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world, Whereas disregard and contempt for human rights have resulted in barbarous acts which have outraged the conscience of mankind, and the advent of a world in which human beings shall enjoy freedom of speech and belief and freedom from fear and want has been proclaimed as the highest aspiration of the common people, Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be pro- tected by the rule of law, Whereas it is essential to promote the development of friendly relations between nations, Whereas the peoples of the United Nations have in the Charter reaffirmed their faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity and worth of the human person and in the equal rights of men and women and have determined to promote social progress and better standards of life in larger freedom, Whereas Member States have pledged themselves to achieve, in co-operation with the United Nations, the promotion of universal respect for and observance of human rights and fundamental freedoms, Whereas a common understanding of these rights and freedoms is of the great- est importance for the full realization -

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot

2021 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Lead Actor In A Comedy Series Tim Allen as Mike Baxter Last Man Standing Brian Jordan Alvarez as Marco Social Distance Anthony Anderson as Andre "Dre" Johnson black-ish Joseph Lee Anderson as Rocky Johnson Young Rock Fred Armisen as Skip Moonbase 8 Iain Armitage as Sheldon Young Sheldon Dylan Baker as Neil Currier Social Distance Asante Blackk as Corey Social Distance Cedric The Entertainer as Calvin Butler The Neighborhood Michael Che as Che That Damn Michael Che Eddie Cibrian as Beau Country Comfort Michael Cimino as Victor Salazar Love, Victor Mike Colter as Ike Social Distance Ted Danson as Mayor Neil Bremer Mr. Mayor Michael Douglas as Sandy Kominsky The Kominsky Method Mike Epps as Bennie Upshaw The Upshaws Ben Feldman as Jonah Superstore Jamie Foxx as Brian Dixon Dad Stop Embarrassing Me! Martin Freeman as Paul Breeders Billy Gardell as Bob Wheeler Bob Hearts Abishola Jeff Garlin as Murray Goldberg The Goldbergs Brian Gleeson as Frank Frank Of Ireland Walton Goggins as Wade The Unicorn John Goodman as Dan Conner The Conners Topher Grace as Tom Hayworth Home Economics Max Greenfield as Dave Johnson The Neighborhood Kadeem Hardison as Bowser Jenkins Teenage Bounty Hunters Kevin Heffernan as Chief Terry McConky Tacoma FD Tim Heidecker as Rook Moonbase 8 Ed Helms as Nathan Rutherford Rutherford Falls Glenn Howerton as Jack Griffin A.P. Bio Gabriel "Fluffy" Iglesias as Gabe Iglesias Mr. Iglesias Cheyenne Jackson as Max Call Me Kat Trevor Jackson as Aaron Jackson grown-ish Kevin James as Kevin Gibson The Crew Adhir Kalyan as Al United States Of Al Steve Lemme as Captain Eddie Penisi Tacoma FD Ron Livingston as Sam Loudermilk Loudermilk Ralph Macchio as Daniel LaRusso Cobra Kai William H. -

Dædalus Issue Is “Witnessing Climate Change

Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences Fall 2020 Witnessing Climate Change Nancy L. Rosenblum, guest editor with Robert Jay Lifton · Naomi Oreskes Robert H. Socolow · Dennis F. Thompson Michael B. Gerrard · Mark A. Mitchell Patrick L. Kinney · Rebecca Henderson David W. Titley · Elke U. Weber · Jessica F. Green Rafe Pomerance · Carolyn Kormann Scott Gabriel Knowles · Antonio Oposa Jr. Dædalus Journal of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences “Witnessing Climate Change” Volume 149, Number 4; Fall 2020 Nancy L. Rosenblum, Guest Editor Phyllis S. Bendell, Managing Editor and Director of Publications Peter Walton, Associate Editor Heather M. Struntz, Assistant Editor Committee on Studies and Publications John Mark Hansen, Chair; Rosina Bierbaum, Johanna Drucker, Gerald Early, Carol Gluck, Linda Greenhouse, John Hildebrand, Philip Khoury, Arthur Kleinman, Sara Lawrence-Lightfoot, Alan I. Leshner, Rose McDermott, Michael S. McPherson, Frances McCall Rosenbluth, Scott D. Sagan, Nancy C. Andrews (ex officio), David W. Oxtoby (ex officio), Diane P. Wood (ex officio) Inside front cover: Unknown artist, The Dramatic Birth of a Giant Iceberg, originally printed in The Popular Science Educator, Volume 2, edited by Charles Ray (London: The Amalgamated Press, 1935). Contents 6 Introduction: Paths to Witnessing, Ethics of Speaking Out Nancy L. Rosenblum 25 On Becoming Witnessing Professionals Robert Jay Lifton 33 What Is the Social Responsibility of Climate Scientists? Naomi Oreskes 46 Witnessing for the Middle to Depolarize the Climate Change Conversation Robert H. Socolow 67 The Professional Ethics of Witnessing Professionals Dennis F. Thompson 79 An Environmental Lawyer’s Fraught Quest for Legal Tools to Hold Back the Seas Michael B. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 477 963 CG 032 427 TITLE Television: Alcohol's Vast Adland. PUB DATE 2002-12-18 NOTE 22p.; Produced by the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth. AVAILABLE FROM Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth, Georgetown University, 2233 Wisconsin Ave., NW, Suite 525, Washington, DC 20007. Tel: 202-687-1019; Web site: www.camy.org. For full text: http://camy.org/research/tv1202/. PUB TYPE Numerical/Quantitative Data (110) Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Advertising; *Alcoholic Beverages; Drinking; Marketing; *Mass Media Effects; Television; *Youth ABSTRACT Concern about how much television alcohol advertising reaches underage youth and how the advertising influences their attitudes and decisions about alcohol use has been widespread for many years. Lacking in the policy debate has been solid, reliable information about the extent of youth exposure to television alcohol advertising. To address this critical gap, the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth commissioned Virtual Media Resources, a media planning and research firm in Natick, Massachusetts, to analyze television alcohol advertising in 2001, using the same data and methodology as professional media planners. In auditing 208,909 alcohol ad placements on television in 2001, the Center on Alcohol Marketing and Youth found the following: the alcohol industry's voluntary guidelines for ad placements on television are so lax that they allow the substantial exposure of youth to alcoholic beverage advertising, including advertising on programs with disproportionate numbers of young people in the viewing audience; even when adults were more likely to see television alcohol advertising than youth, in many instances youth saw almost as much television alcohol advertising as the adults; and because of the placement of the commercials, almost a quarter of alcohol advertising on television in 2001 was more likely to be seen by youth than adults.(Author) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

Prophet Singer: the Voice and Vision of Woody Guthrie Mark Allan Jackson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2002 Prophet singer: the voice and vision of Woody Guthrie Mark Allan Jackson Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jackson, Mark Allan, "Prophet singer: the voice and vision of Woody Guthrie" (2002). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 135. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/135 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. PROPHET SINGER: THE VOICE AND VISION OF WOODY GUTHRIE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Mark Allan Jackson B.A., Hendrix College, 1988 M.A., University of Arkansas at Fayetteville, 1995 December 2002 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many people and institutions should be acknowledged for their help in making my dissertation possible. I have to start off by tipping my hat to certain of my friends, people who first asked me interesting questions or spared with me in argument about music. So I salute Casey Whitt, John Snyder, Cody Walker, Derek Van Lynn, Maxine Beach, and Robin Becker. They helped me see the deep places in America’s music, made me think about its beauty and meaning. -

City of Savannah, GA New Business Listing January 2012 Account

City of Savannah, GA New Business Listing January 2012 Account Date Telephone Number Opened Business Name Business Address Zip Business Description Number 282176 1/5/2012 YARD GUARDS 2404 NEW YORK AVE 31404 LANDSCAPING SERVICES (912) 220-4994 225945 1/17/2012 IN DA HOUSE ENTERTAINMENT, LLC 8400 ABERCORN ST # A102 31406 PROMOTERS OF PERFORMING ARTS, SPORTS, AND SIMILAR EVENTS WITHOUT FACILITIES (912) 308-5097 035548 1/3/2012 REAL MCCOY ENTERTAINMENT 509 E 40TH 31401 PROMOTERS OF PERFORMING ARTS, SPORTS, AND SIMILAR EVENTS WITHOUT FACILITIES (912) 220-8938 035549 1/3/2012 INSTANT TAX SERVICE 6606 WATERS AVE 31406 INCOME TAX PREPARATION (912) 354-5527 035550 1/3/2012 WELLINGTON PROFESSIONAL 2920 STONEWALL PL 32773 DRYWALL, PLASTERING, ACOUSTIC & INSULATION CONTRACTOR (407) 322-4577 035552 1/3/2012 DYKES CLEANING SERVICE 13 TALINA LN # UNIT F 31419 JANITORIAL SERVICES (404) 416-7117 035553 1/3/2012 BROUGHTON MARKET 32 EAST BROUGHTON STREET 31401 RETAIL BEER & WINE PACKAGE ONLY (912) 659-9884 035554 1/3/2012 LET'S SEE SAVANNAH 28 DRAYTON ST 31401 TOURIST GUIDE SERVICES (REGULATED) (912) 414-1357 035555 1/3/2012 SAVANNAH ECO MOWING, LLC 2218 E 58TH ST 31404 LANDSCAPING SERVICES (912) 373-5030 035557 1/3/2012 MARY DAVIS-BROWN 1834 CAPTIAL ST 31404 ELECTRONIC SHOPPING INTERNET SALES (912) 398-9739 035558 1/3/2012 JAY MAA SHAKI FOODMART 1516 MONTGOMERY ST 31401 CONVENIENCE STORES (912) 238-5795 035559 1/3/2012 I CARE FAMILY MEDICINE CLINIC 3840 WATERS AVE 31404 OFFICES OF PHYSICIANS (EXCEPT MENTAL HEALTH SPECIALISTS) (770) 403-5382 035560 1/3/2012 ULTIMATE SALES & SERVICES INC 615 STEPHENSON AVE # 101 31405 ADMINISTRATION MANAGEMENT SERVICES (540) 379-1045 035561 1/4/2012 RONALD R. -

San Diego Public Library New Additions April 2012

San Diego Public Library New Additions April 2012 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes MP3 Audiobooks Audiovisual Materials Music Scores Biographies Newspaper Room Fiction Call # Author Title [MYST] FIC/ALEXANDER Alexander, Gary Zillionaire : a Buster Hightower mystery [MYST] FIC/AYKOL Aykol, Esmahan Hotel Bosphorus [MYST] FIC/BABSON Babson, Marian. No cooperation from the cat : a mystery [MYST] FIC/BALL Ball, Toby. Scorch city [MYST] FIC/BENN Benn, James R. A mortal terror : A Billy Boyle World War II mystery [MYST] FIC/BLAEDEL Blædel, Sara. Call me princess [MYST] FIC/BORG Borg, Todd. Tahoe deathfall [MYST] FIC/BORGER Borger, Judith Yates Whose hand? : a Skeeter Hughes mystery [MYST] FIC/BORK Bork, Lisa In sickness and in death : a broken vows mystery [MYST] FIC/BRAND Brand, Axel. The dead genius : a Lieutenant Joe Sonntag novel [MYST] FIC/BRETT Brett, Simon. Bones under the beach hut : a Fethering mystery [MYST] FIC/BRIGHTWELL Brightwell, Emily. Mrs. Jeffries and the mistletoe mix‐up [MYST] FIC/BROWN Brown, Rita Mae. The big cat nap : the 20th anniversary Mrs. Murphy mystery [MYST] FIC/BRUCE Bruce, Alison. The calling [MYST] FIC/CLARK Clark, Carol Higgins. Gypped : a Regan Reilly mystery [MYST] FIC/CLELAND Cleland, Jane K. Dolled up for murder [MYST] FIC/COTTERILL Cotterill, Colin. Love songs from a shallow grave : [a Dr. Siri investigation set in Laos] [MYST] FIC/CRAIG Craig, James London calling [MYST] FIC/DAMS Dams, Jeanne M.