Native Americans on Television in the Late 20 and Early 21 Centuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

James Baldwin As a Writer of Short Fiction: an Evaluation

JAMES BALDWIN AS A WRITER OF SHORT FICTION: AN EVALUATION dayton G. Holloway A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1975 618208 ii Abstract Well known as a brilliant essayist and gifted novelist, James Baldwin has received little critical attention as short story writer. This dissertation analyzes his short fiction, concentrating on character, theme and technique, with some attention to biographical parallels. The first three chapters establish a background for the analysis and criticism sections. Chapter 1 provides a biographi cal sketch and places each story in relation to Baldwin's novels, plays and essays. Chapter 2 summarizes the author's theory of fiction and presents his image of the creative writer. Chapter 3 surveys critical opinions to determine Baldwin's reputation as an artist. The survey concludes that the author is a superior essayist, but is uneven as a creator of imaginative literature. Critics, in general, have not judged Baldwin's fiction by his own aesthetic criteria. The next three chapters provide a close thematic analysis of Baldwin's short stories. Chapter 4 discusses "The Rockpile," "The Outing," "Roy's Wound," and "The Death of the Prophet," a Bi 1 dungsroman about the tension and ambivalence between a black minister-father and his sons. In contrast, Chapter 5 treats the theme of affection between white fathers and sons and their ambivalence toward social outcasts—the white homosexual and black demonstrator—in "The Man Child" and "Going to Meet the Man." Chapter 6 explores the theme of escape from the black community and the conseauences of estrangement and identity crises in "Previous Condition," "Sonny's Blues," "Come Out the Wilderness" and "This Morning, This Evening, So Soon." The last chapter attempts to apply Baldwin's aesthetic principles to his short fiction. -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

How Bigger Was Born Anew

Fall 2020 29 ow Bier as Born new datation Reuration and Double Consciousness in Nambi E elle’s Native Son Isaiah Matthew Wooden This essay analyzes Nambi E. Kelley’s stage adaptation of Native Son to consider the ways tt Aicn Aeicn is itlie by n constitte to cts o etion t sharpens particular focus on how Kelley reinvigorates Wright’s novel’s searing social and cil cities by ctiely ein te oisin etpo o oble consciosness n iin ne o, enin, n se to te etpo, elleys Native Son extends the debates about “the problem of the color line” that Du Bois’s writing helped engender at te beinnin o te tentiet centy into te tentyst n, in so oin, opens citicl space to reckon with the persistent and pernicious problem of anti-Black racism. ewords adaptation, refguration, double consciousness, Native Son, Nambi E. Kelley This essay takes as a central point of departure the claim that African American drama is vitalized by and, indeed, constituted through acts of refguration. It is such acts that endow the remarkably capacious genre with any sense or semblance of coherence. Retion is notably a word with multiple signifcations. It calls to mind processes of representation and recalculation. It also points to matters of meaning-making and modifcation. The pref re does important work here, suggesting change, alteration, or even improvement. For the purposes of this essay, I use etion to refer to the strategies, practices, methods, and techniques that African American dramatists deploy to transform or give new meaning to certain ideas, concepts, artifacts, and histories, thereby opening up fresh interpretive and defnitional possibilities and, when appropriate, prompting much-needed reckonings. -

Family Law Section Commentator

The Florida Bar FAMILY LAW SECTION COMMENTATOR Spring 2019 Anya Cintron Stern, Esq. – Co-Editor Volume 1, No. 2 Anastasia Garcia, Esq. – Co-Editor The Commentator is prepared and published by the Family Law Section of The Florida Bar ABIGAIL BEEBE, WEST PALM BEACH – Chair AMY C. HAMLIN, ALTAMONTE SPRINGS – Chair-Elect DOUGLAS A. GREENBAUM, FORT LAUDERDALE – Treasurer HEATHER L. APICELLA, BOCA RATON – Secretary NICOLE L. GOETZ – Immediate Past Chair LAURA DAVIS SMITH, CORAL GABLES and SONJA JEAN, CORAL GABLES – Publications Committee Co-Chairs WILLE MAE SHEPHERD, TALLAHASSEE — Administrator DONNA RICHARDSON, TALLAHASSEE — Design & Layout Statements of opinion or comments appearing herein are those of the authors and contributors and not of The Florida Bar or the Family Law Section. Articles and cover photos to be considered for publication may be submitted to Anya Cintron Stern, Esq. ([email protected]), or Anastasia Garcia, Esq. ([email protected]), Co-Chairs of the Commentator. MS Word format is preferred for documents, and jpeg images for photos. ON THE COVER: Photograph courtesy Heather Apicella INSIDE THIS ISSUE 3 Message from the Chair 17 Addicition and Its Impact on Our Cases and Our Profession: First Article of Three 6 Comments from the Co-Chairs of the Publications Committee 21 Navigating Turbulent Waters: Dealing with Domestic Violence in a Divorce 7 Message from the Co-Chairs of the Commentator 26 Family Law Section In-State Retreat (Photos) 7 Section Calendar 31 Crafting Developmentally Appropriate Parenting Plans for Infants and Toddlers 8 Guest Editor's Corner 36 Psychosexual Evaluations in Family Law 11 Stress in Family Law Practice-Is There A Better Way For Families and 47 Shifting Gears: Making The Most of Life’s Practitioners Not-So-Little Changes Family Law Commentator 2 Spring 2019 Message from the Chair Abigail M. -

Television Shows

Libraries TELEVISION SHOWS The Media and Reserve Library, located on the lower level west wing, has over 9,000 videotapes, DVDs and audiobooks covering a multitude of subjects. For more information on these titles, consult the Libraries' online catalog. 1950s TV's Greatest Shows DVD-6687 Age and Attitudes VHS-4872 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-2780 Discs Age of AIDS DVD-1721 24 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6678 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-2780 Discs Age of Kings, Volume 2 (Discs 4-5) DVD-6679 Discs 24 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-2780 Discs Alfred Hitchcock Presents Season 1 DVD-7782 24 Season 2 (Discs 1-4) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6165 Discs 24 Season 2 (Discs 5-7) DVD-2282 Discs Alias Season 1 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6165 Discs 30 Days Season 1 DVD-4981 Alias Season 2 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 2 DVD-4982 Alias Season 2 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6171 Discs 30 Days Season 3 DVD-3708 Alias Season 3 (Discs 1-4) DVD-7355 Discs 30 Rock Season 1 DVD-7976 Alias Season 3 (Discs 5-6) DVD-7355 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 1-3) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 1-3) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 4 (Discs 4-6) DVD-6177 Discs 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-5) c.1 DVD-5583 Discs Alias Season 5 DVD-6183 90210 Season 1 (Discs 4-6) c.2 DVD-5583 Discs All American Girl DVD-3363 Abnormal and Clinical Psychology VHS-3068 All in the Family Season One DVD-2382 Abolitionists DVD-7362 Alternative Fix DVD-0793 Abraham and Mary Lincoln: A House -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

Simply Folk Sing-Along 2018 If I Had a Hammer If I Had a Hammer, I'd Hammer in the Morning, I'd Hammer in the Evening, All Over

Simply Folk Sing-Along 2018 If I Had a Hammer If I had a hammer, I'd hammer in the morning, I'd hammer in the evening, all over this land I'd hammer out danger, I'd hammer out a warning I'd hammer out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land If I had a bell, I'd ring it in the morning, I'd ring it in the evening, all over this land I'd ring out danger, I'd ring out a warning I'd ring out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land If I had a song, I'd sing it in the morning, I'd sing it in the evening, all over this land I'd sing out danger, I'd sing out a warning I'd sing out love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land Well I've got a hammer, and I've got a bell, and I've got a song to sing, all over this land It's the hammer of justice, it's the bell of freedom It's the song about love between my brothers and my sisters, all over this land You Are My Sunshine The other night dear as I lay sleeping, I dreamed I held you in my arms, But when I woke dear I was mistaken, and I hung my head and I cried You are my sunshine, my only sunshine, you make me happy when skies are gray, You'll never know dear, how much I love you, please don't take my sunshine away I'll always love you and make you happy, if you will only say the same, But if you leave me and love another, you’ll regret it all someday You told me once dear, you really loved me, and no one could come between, But now you've left me to love another, you have shattered all of my dreams In all my dreams, dear, you seem to leave me; when I awake my poor heart pains So won’t you come back and make me happy, I’ll forgive, dear, I’ll take all the blame City of New Orleans Riding on the City of New Orleans, Illinois Central Monday morning rail Fifteen cars and fifteen restless riders, three conductors and twenty-five sacks of mail. -

Pritchett K.D

Pritchett k.d. lang Volume 4, Number 1, January 5, 1994 FREE PHOTO: JEFF HELBERG Why the -.;:. legislator as the "yuppie ninjas" - have passed Chozen-ji Zen through the dojo's gates temple and martial to "talk story" with artsdojo in upper Tanouye, including the governor, a number of Kalihi Valley just legislators, at least one might be one of the Bishop Estate trustee, developer Herbert most important Horita, big-gun lawyer places you've never Wally Fujiyama, banking CEO Uonel Tokioka and a heard of couple of men known widely as behind-the scenes "arrangers." A couple of notorious underworld figures have also been known to go to Chozen-ji, and even the FBl's curiosity has appar ently been stirred by rumors of the dojo's powerconnections. From one perspective, it looks like a conspiracy theorist's dream. But f there's one thing this press. Chozen-ji is a Zen talk to a dojo follower town has a reputation Buddhist temple and and you'll get quite a dif.. Iforbesides mai tais somewhat exclusive cen ferent picture, one of an and hula girls, it's secre ter for the martial, fine angel network of tive power cliques that and healing arts headed dedicated people, as cut back-room deals far by locally born archbishop well intentioned as they from the public eye. The Tanouye Tenshin Roshi are connected, nurturing kinds of "hot spots" (roshiisan hope with the Story by where the influential con honorific title DEREK FERRAR guidance of gregate are many: the used for Tanouye. From golflinks, the Pacific heads of Zen temples), this perspective, the Club, reunions of the who teaches the samurai activities of the roshi 442nd Regiment, Vegas. -

Paul Green Foundation

Paul Green Foundation NEWS – October 2017 Native Son’s New Adaptation PAUL GREEN ANNUAL MEETING Playwright Nambi Kelley NOVEMBER 4, 2017 has written plays for NC BOTANICAL GARDEN Steppenwolf, Goodman Theatre and Lincoln Center CHAPEL HILL, NC and most recently was named playwright-in-residence at The 2017 the National Black Theatre in New York. Kelley’s adaptation of Native Son was National Theatre Conference presented to critical acclaim for the premiere December 1-3 in New York City production at the Court Theatre/American Blues Each year the National Theatre Conference Festival. Since that first production it has been Person of the Year names the Paul Green produced in New York, California, Georgia and Award winner. This year’s Person of the Year – Arizona, and published by Samuel French in 2016. Molly Smith selected June Schreiner, a highly The Green Foundation joined with the Wright acclaimed young actor. Since 1989, the Paul Estate to sanction these productions. Green Foundation has honored a “young theatre professional” with this Paul Green Award. A bit of history: Paul Green and Richard Wright’s Native Son that opened on March 24, Founded in 1925, the National Theatre 1941, at the St. James Theatre in New York City, Conference is a not-for-profit organization made was produced by Orson Welles and John up of distinguished members of the American Houseman. Of the very serious disagreement that Theatre Community; Green was instrumental in ensued between Green and Wright, Dr. Laurence the founding the organization and served as Avery, Professor Emeritus, UNC-Chapel Hill president in the early years. -

Scriptedpifc-01 Banijay Aprmay20.Indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights Presents… Bäckström the Hunt for a Killer We Got This Thin Ice

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | April/May 2020 Television e Interview Virtual thinking The Crown's Andy Online rights Business Harries on what's companies eye next for drama digital disruption TBI International Page 10 Page 12 pOFC TBI AprMay20.indd 1 20/03/2020 20:25 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. sadistic murder case that had remained unsolved for 16 years. most infamous unsolved murder case? climate change, geo-politics and Arctic exploitation. Bang The Gulf GR5: Into The Wilderness Rebecka Martinsson When a young woman vanishes without a trace In a brand new second season, a serial killer targets Set on New Zealand’s Waiheke Island, Detective Jess Savage hiking the famous GR5 trail, her friends set out to Return of the riveting crime thriller based on a group of men connected to a historic sexual assault. investigates cases while battling her own inner demons. solve the mystery of her disappearance. the best-selling novels by Asa Larsson. banijayrights.com ScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay AprMay20.indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Citizen Kane Ebook, Epub

CITIZEN KANE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Harlan Lebo | 368 pages | 01 May 2016 | Thomas Dunne Books | 9781250077530 | English | United States Citizen Kane () - IMDb Mankiewicz , who had been writing Mercury radio scripts. One of the long-standing controversies about Citizen Kane has been the authorship of the screenplay. In February Welles supplied Mankiewicz with pages of notes and put him under contract to write the first draft screenplay under the supervision of John Houseman , Welles's former partner in the Mercury Theatre. Welles later explained, "I left him on his own finally, because we'd started to waste too much time haggling. So, after mutual agreements on storyline and character, Mank went off with Houseman and did his version, while I stayed in Hollywood and wrote mine. The industry accused Welles of underplaying Mankiewicz's contribution to the script, but Welles countered the attacks by saying, "At the end, naturally, I was the one making the picture, after all—who had to make the decisions. I used what I wanted of Mank's and, rightly or wrongly, kept what I liked of my own. The terms of the contract stated that Mankiewicz was to receive no credit for his work, as he was hired as a script doctor. Mankiewicz also threatened to go to the Screen Writers Guild and claim full credit for writing the entire script by himself. After lodging a protest with the Screen Writers Guild, Mankiewicz withdrew it, then vacillated. The guild credit form listed Welles first, Mankiewicz second. Welles's assistant Richard Wilson said that the person who circled Mankiewicz's name in pencil, then drew an arrow that put it in first place, was Welles. -

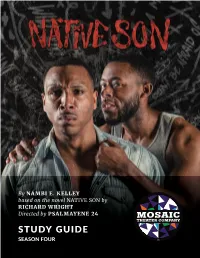

STUDY GUIDE SEASON FOUR Introduction

By NAMBI E. KELLEY based on the novel NATIVE SON by RICHARD WRIGHT Directed by PSALMAYENE 24 STUDY GUIDE SEASON FOUR Introduction “Theatre is a form of knowledge; it should and can also be a means of transforming society. Theatre can help us build our future, rather than just waiting for it.”—Augusto Boal The purpose and goal of Mosaic’s education department is simple. Our program aims to further and cultivate students’ knowledge and passion for theatre and theatre education. We strive for complete and exciting arts engagement for educators, artists, our community, and all learners in the classroom. Mosaic’s education program yearns to be a conduit for open discussion and connection to help students understand how theatre can make a profound impact in their lives, in society, and in their communities. Mosaic Theater Company of DC is thrilled to have your interest and support! Catherine Chmura Arts Education Apprentice—Mosaic Theater Company of DC Written by Catherine Chmura, Khalid Y. Long, and Isaiah M. Wooden 2 NATIVE SON MOSAIC THEATER COMPANY of DC PRESENTS NATIVE SON By Nambi E. Kelley based on the novel NATIVE SON by Richard Wright Directed by Psalmayene 24 Set Designer: Ethan Sinnott Lighting Designer: William K. D’Eugenio Costume Designer: Katie Touart Projections Designer: Dylan Uremovich Sound Designer: Nick Hernandez Properties Designer: Willow Watson Movement Specialist: Tony Thomas* Production Stage Manager: Simone Baskerville* Dramaturg: Isaiah M. Wooden & Khalid Yaya Long Table of Contents Curriculum Connections: DC Public