Renaissance Themes and Figures in Browning's Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town-Talk and the Cause Célèbre of Robert Browning's the Ring And

Dominican Scholar Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship Faculty and Staff Scholarship 5-2016 Town-Talk and the Cause Célèbre of Robert Browning’s The Ring and the Book Amy R. Wong Department of Literature and Languages, Dominican University of California, [email protected] https://doi.org/10.1086/685427 Survey: Let us know how this paper benefits you. Recommended Citation Wong, Amy R., "Town-Talk and the Cause Célèbre of Robert Browning’s The Ring and the Book" (2016). Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship. 294. https://doi.org/10.1086/685427 DOI http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/685427 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty and Staff Scholarship at Dominican Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Collected Faculty and Staff Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Dominican Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Town Talk and the Cause Célèbre of Robert Browning’s The Ring and the Book AMY R. WONG Dominican University of California There prattled they, discoursed the right and wrong, Turned wrong to right, proved wolves sheep and sheep wolves. (Robert Browning, The Ring and the Book [1868–69])1 These lines from Robert Browning’s ambitious, blank-verse epic, The Ring and the Book, describe the town talkers of late seventeenth-century Rome as they witness the proceedings of a triple-murder trial. Speaking in pro- pria persona, Browning seems disdainful of the relativistic abandon of “prattle” that “proved wolves sheep and sheep wolves.” Yet the explicit premise of The Ring and the Book is to reanimate talkers—from the dead material of print—who fail, more often than not, to provide clear moral judgments. -

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature

A Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor RESEARCH IN MEDIEVAL CULTURE Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Medieval Institute Publications is a program of The Medieval Institute, College of Arts and Sciences Bibliographical Guide to the Study of the Troubadours and Old Occitan Literature Robert A. Taylor MEDIEVAL INSTITUTE PUBLICATIONS Western Michigan University Kalamazoo Copyright © 2015 by the Board of Trustees of Western Michigan University All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Taylor, Robert A. (Robert Allen), 1937- Bibliographical guide to the study of the troubadours and old Occitan literature / Robert A. Taylor. pages cm Includes index. Summary: "This volume provides offers an annotated listing of over two thousand recent books and articles that treat all categories of Occitan literature from the earli- est enigmatic texts to the works of Jordi de Sant Jordi, an Occitano-Catalan poet who died young in 1424. The works chosen for inclusion are intended to provide a rational introduction to the many thousands of studies that have appeared over the last thirty-five years. The listings provide descriptive comments about each contri- bution, with occasional remarks on striking or controversial content and numerous cross-references to identify complementary studies or differing opinions" -- Pro- vided by publisher. ISBN 978-1-58044-207-7 (Paperback : alk. paper) 1. Provençal literature--Bibliography. 2. Occitan literature--Bibliography. 3. Troubadours--Bibliography. 4. Civilization, Medieval, in literature--Bibliography. -

The Armstrong Browning Library Newsletter God Is the Perfect Poet

The Armstrong Browning Library Newsletter God is the perfect poet. – Paracelsus by Robert Browning NUMBER 51 SPRING/SUMMER 2007 WACO, TEXAS Ann Miller to be Honored at ABL For more than half a century, the find inspiration. She wrote to her sister late Professor Ann Vardaman Miller of spending most of the summer there was connected to Baylor’s English in the “monastery like an eagle’s nest Department—first as a student (she . in the midst of mountains, rocks, earned a B.A. in 1949, serving as an precipices, waterfalls, drifts of snow, assistant to Dr. A. J. Armstrong, and a and magnificent chestnut forests.” master’s in 1951) and eventually as a Master Teacher of English herself. So Getting to Vallombrosa was not it is fitting that a former student has easy. First, the Brownings had to stepped forward to provide a tribute obtain permission for the visit from to the legendary Miller in Armstrong the Archbishop of Florence and the Browning Library, the location of her Abbot-General. Then, the trip itself first campus office. was arduous—it involved sitting in a wine basket while being dragged up the An anonymous donor has begun the cliffs by oxen. At the top, the scenery process of dedicating a stained glass was all the Brownings had dreamed window in the Cox Reception Hall, on of, but disappointment awaited Barrett the ground floor of the library, to Miller. Browning. The monks of the monastery The Vallombrosa Window in ABL’s Cox Reception The hall is already home to five windows, could not be persuaded to allow a woman Hall will be dedicated to the late Ann Miller, a Baylor professor and former student of Dr. -

The Elements of Poet :Y

CHAPTER 3 The Elements of Poet :y A Poetry Review Types of Poems 1, Lyric: subjective, reflective poetry with regular rhyme scheme and meter which reveals the poet’s thoughts and feelings to create a single, unique impres- sion. Matthew Arnold, "Dover Beach" William Blake, "The Lamb," "The Tiger" Emily Dickinson, "Because I Could Not Stop for Death" Langston Hughes, "Dream Deferred" Andrew Marvell, "To His Coy Mistress" Walt Whitman, "Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking" 2. Narrative: nondramatic, objective verse with regular rhyme scheme and meter which relates a story or narrative. Samuel Taylor Coleridge, "Kubla Khan" T. S. Eliot, "Journey of the Magi" Gerard Manley Hopkins, "The Wreck of the Deutschland" Alfred, Lord Tennyson, "Ulysses" 3. Sonnet: a rigid 14-line verse form, with variable structure and rhyme scheme according to type: a. Shakespearean (English)--three quatrains and concluding couplet in iambic pentameter, rhyming abab cdcd efe___~f gg or abba cddc effe gg. The Spenserian sonnet is a specialized form with linking rhyme abab bcbc cdcd ee. R-~bert Lowell, "Salem" William Shakespeare, "Shall I Compare Thee?" b. Italian (Petrarchan)--an octave and sestet, between which a break in thought occurs. The traditional rhyme scheme is abba abba cde cde (or, in the sestet, any variation of c, d, e). Elizabeth Barrett Browning, "How Do I Love Thee?" John Milton, "On His Blindness" John Donne, "Death, Be Not Proud" 4. Ode: elaborate lyric verse which deals seriously with a dignified theme. John Keats, "Ode on a Grecian Urn" Percy Bysshe Shelley, "Ode to the West Wind" William Wordsworth, "Ode: Intimations of Immortality" Blank Verse: unrhymed lines of iambic pentameter. -

Gcse English Literature (8702)

GCSE ENGLISH LITERATURE (8702) Past and present: poetry anthology For exams from 2017 Version 1.0 June 2015 AQA_EngLit_GCSE_v08.indd 1 31/07/2015 22:14 AQA GCSE English Literature Past and present: poetry anthology All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing on any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the publisher, except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of the licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Notice to teachers: It is illegal to reproduce any part of this work in material form (including photocopying and electronic storage) except under the following circumstances: i) where you are abiding by a licence granted to your school or institution by the Copyright Licensing Agency; ii) where no such licence exists, or where you wish to exceed the terms of a licence, and you have gained the written permission of The Publishers Licensing Society; iii) where you are allowed to reproduce without permission under the provisions of Chapter 3 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Photo permissions 5 kieferpix / Getty Images, 6 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 8 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 9 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 11 Georgios Kollidas/Fotolia, 12 Photos.com/Thinkstock, 13 Stuart Clarke/REX, 16 culture-images/Lebrecht, 16,© Pictorial Press Ltd/Alamy, 17 Topfoto.co.uk, 18 Schiffer-Fuchs/ullstein -

Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning Was a Romantic Poet in Great Effect When Disclosing a Macabre Or Every Sense of the Word

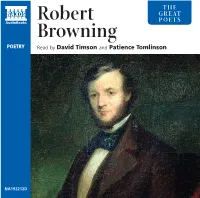

THE GREAT Robert POETS Browning POETRY Read by David Timson and Patience Tomlinson NA192212D 1 How They Brought the Good News from Ghent to Aix 3:49 2 Life in a Love 1:11 3 A Light Woman 3:42 4 The Statue and the Bust 15:16 5 My Last Duchess 3:53 6 The Confessional 4:59 7 A Grammarian’s Funeral 8:09 8 The Pied Piper of Hamelin 7:24 9 ‘You should have heard the Hamelin people…’ 8:22 10 The Lost Leader 2:24 11 Soliloquy of the Spanish Cloister 3:55 12 The Laboratory 3:40 13 Porphyria’s Lover 3:47 14 Evelyn Hope 3:49 15 Home Thoughts from Abroad 1:19 16 Pippa’s Song 0:32 Total time: 76:20 = David Timson = Patience Tomlinson 2 Robert Browning (1812–1889) Robert Browning was a romantic poet in great effect when disclosing a macabre or every sense of the word. He was an ardent evil narrative, as in The Laboratory, or The lover who wooed the poet Elizabeth Confessional or Porphyria’s Lover. Barrett despite fierce opposition from Sometimes Browning uses this matter- her tyrannical father, while as a poet – of-fact approach to reduce a momentous inheriting the mantle of Wordsworth, occasion to the colloquial – in The Keats and Shelley – he sought to show, Grammarian’s Funeral, for instance, in in the Romantic tradition, man’s struggle which a scholar has spent his life pursuing with his own nature and the will of God. knowledge at the expense of actually But Browning was no mere imitator of enjoying life itself. -

Sight and Touch in the Noli Me Tangere

Chapter 1 Sight and Touch in the Noli me tangere Andrea del Sarto painted his Noli me tangere (Fig. 1) at the age of twenty-four.1 He was young, ambitious, and grappling for the first time with the demands of producing an altarpiece. He had his reputation to consider. He had the spiri- tual function of his picture to think about. And he had his patron’s wishes to address. I begin this chapter by discussing this last category of concern, the complex realities of artistic patronage, as a means of emphasizing the broad- er arguments of my book: the altarpiece commissions that Andrea received were learning opportunities, and his artistic decisions serve as indices of the religious knowledge he acquired in the course of completing his professional endeavors. Throughout this particular endeavor—from his first client consultation to the moment he delivered the Noli me tangere to the Augustinian convent lo- cated just outside the San Gallo gate of Florence—Andrea worked closely with other members of his community. We are able to identify those individuals only in a general sense. Andrea received his commission from the Morelli fam- ily, silk merchants who lived in the Santa Croce quarter of the city and who frequently served in the civic government. They owned the rights to one of the most prestigious chapels in the San Gallo church. It was located close to the chancel, second to the left of the apse.2 This was prime real estate. Renaissance churches were communal structures—always visible, frequently visited. They had a natural hierarchy, dominated by the high altar. -

The Strange Art of 16Th –Century Italy

The Strange Art of 16th –century Italy Some thoughts before we start. This course is going to use a seminar format. Each of you will be responsible for an artist. You will be giving reports on- site as we progress, in as close to chronological order as logistics permit. At the end of the course each of you will do a Power Point presentation which will cover the works you treated on-site by fitting them into the rest of the artist’s oeuvre and the historical context.. The readings: You will take home a Frederick Hartt textbook, History of Italian Renaissance Art. For the first part of the course this will be your main background source. For sculpture you will have photocopies of some chapters from Roberta Olsen’s book on Italian Renaissance sculpture. I had you buy Walter Friedlaender’s Mannerism and Anti-Mannerism in Italian Painting, first published in 1925. While recent scholarship does not agree with his whole thesis, many of his observations are still valid about the main changes at the beginning and the end of the 16th century. In addition there will be some articles copied from art history periodicals and a few provided in digital format which you can read on the computer. Each of you will be doing other reading on your individual artists. A major goal of the course will be to see how sixteenth-century art depends on Raphael and Michelangelo, and to a lesser extent on Leonardo. Art seems to develop in cycles. What happens after a moment of great innovations? Vasari, in his Lives of the Artists, seems to ask “where do we go from here?” If Leonardo, Raphael and Michelangelo were perfect, how does one carry on? The same thing occurred after Giotto and Duccio in the early Trecento. -

University Microfilms, a XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan

72- 19,021 NAPRAVNIK, Charles Joseph, 1936- CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OF ROBERT BROWNING. The University of Oklahoma, Ph.D. , 1972 Language and Literature, general University Microfilms, A XERQ\Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan (^Copyrighted by Charles Joseph Napravnlk 1972 THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN MICROFILMED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED THE UNIVERSITY OF OKIAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OP ROBERT BROWNING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY BY CHARLES JOSEPH NAPRAVNIK Norman, Oklahoma 1972 CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OF ROBERT BROWNING PROVED DISSERTATION COMMITTEE PLEASE NOTE: Some pages may have indistinct print. Filmed as received. University Microfilms, A Xerox Education Company TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION...... 1 II. BACKGROUND AND RATIONALE.................. 10 III, THE RING, THE CIRCLE, AND IMAGES OF UNITY..................................... 23 IV. IMAGES OF FLOWERS, INSECTS, AND ROSES..................................... 53 V. THE GARDEN IMAGE......................... ?8 VI. THE LANDSCAPE OF LOVE....... .. ...... 105 FOOTNOTES........................................ 126 BIBLIOGRAPHY.............. ...................... 137 iii CONVENTIONAL AND CREATED IMAGERY IN THE LOVE POEMS OP ROBERT BROWNING CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Since the founding of The Browning Society in London in 1881, eight years before the poet*a death, the poetry of Robert -

To the EDITOR of the CLASSICAL REVIEW

THE CLASSICAL REVIEW. 61 then a few of the by-ways. Mr. Browning ling of Admetus's story, and Ixion (Jocoseria), used to know every inch of one highway with its conversion of the transgressor with all its associated by-ways, and never into a newer and more human Prometheus. set his foot on any other highway in the But also there is a word in Gerard de Loiresse same region. If he had been a zoologist, he {Parleyings) for those who might think that would have known all about lions and no- we must go back to myths for all our poetry. thing about tigers. Of course, this is no dis- Outlying stories that he found in his great paragement to his greatness. His true field researches are worked up in EcJietlos and was not learning but life. Only, why could Pfieidippides. He is still constant to the he not have read some Plato ? Our wistful Aeschylus of his youth, and especially to fancy cannot help framing some shadow of the PrometJieus, and to these he adds Pindar the transformed Republic and interpreted and Homer, quoting all three in Roman P/taedrus, for which we could have spared, letters in the midst of his verse. From perhaps, the refutation of Bubb Doding- Homer he is led to consider the ' Homeric ton and the divagations of the Famille question,' and uses it characteristically to Miranda. show forth in allegory the religious edu- Besides interpreting Greek tragedy, he cation of mankind (Asolando, Developments). translated it. The translations of the Alceslis In this period, for the first time in his life, (in Balaustion) and the Hercules Furens (in he begins to add Latin to Greek. -

Browning's Dilemma in Romantic Inheritance: Dramatic Monologue and the Sense of Poetic Career

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kyutacar : Kyushu Institute of Technology Academic Repository Browning's Dilemma in Romantic Inheritance: Dramatic Monologue and the Sense of Poetic Career 著者 虹林 慶 journal or 九州地区国立大学教育系・文系研究論文集 publication title volume 2 number 1 page range No.2 year 2014-10 URL http://hdl.handle.net/10228/00006684 Browning’s Dilemma in Romantic Inheritance: Dramatic Monologue and the Sense of Poetic Career Kyushu Institute of Technology Kei NIJIBAYASHI Browning is often considered to be one of the major successors of Romanticism, especially in any consideration of his versatile handling of love poetry, as in “Love among the Ruins”, or in his apocalyptic, Gothic poems like “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came” and the long, conceptual poems from early in his career: Pauline, Paracelsus and Sordello. However, as Britta Martens argues in Browning, Victorian Poetic and the Romantic Legacy, his inheritance of Romanticism does not enable a straightforward analysis of the specific techniques, themes and styles he adopted. Martens pays close attention to Browning’s ambivalence towards his poetic and private selves, and describes a fraught artistic struggle in the poet’s attachment to and gradual estrangement from Romanticism. One of the causes for Browning’s ambiguity about Romanticism was his urgent need to establish a professional poetic career, unlike the Romantics. 1 (Wordsworth stands as the major exception.) In the creation of the Romantic universe, the sense of career curiously diverged from the business world in favour of the imagination, and triumphant posthumous visions in which the poets gained their artistic and social apotheosis. -

The Tomb of the Author in Robert Browning's Dramatic Monologues

Előd Pál Csirmaz The Tomb of the Author in Robert Browning’s Dramatic Monologues MA Thesis (for MA in English Language and Literature) Eötvös Loránd University (ELTE), Budapest, Hungary, 2006 Supervisor: Péter Dávidházi, Habil. Docent, DSc. Abstract Even after the death of the Author, its remains, its tomb appears to mark a text it cre- ated. Various readings and my analyses of Robert Browning’s six dramatic mono- logues, My Last Duchess, The Bishop Orders His Tomb at Saint Praxed’s Church, Andrea del Sarto, “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came,” Caliban upon Setebos and Rabbi Ben Ezra, suggest that it is not only possible to trace Authorial presence in dramatic monologues, where the Author is generally supposed to be hidden behind a mask, but often it even appears to be inevitable to consider an Authorial entity. This, while problematizes traditional anti-authorial arguments, do not entail the dreaded consequences of introducing an Author, as various functions of the Author and vari- ous Author-related entities are considered in isolation. This way, the domain of metanarrative-like Authorial control can be limited and the Author is turned from a threat into a useful tool in analyses. My readings are done with the help of notions and suggestions derived from two frameworks I introduce in the course of the argument. They not only help in tracing and investigating the Author and related entities, like the Inscriber or the Speaker, but they also provide an alternative description of the genre of the dramatic monologue. Előd P Csirmaz The Tomb of the Author ii Contents 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 THE THEORY OF THE AUTHOR 1 2.1 A History of the Death of the Author 2 2.2 From the Methodological to the Ontological and Back: The Functions of the Author and its Death 3 A.