The Strange Art of 16Th –Century Italy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

March 27, 2018 RESTORATION of CAPPONI CHAPEL in CHURCH of SANTA FELICITA in FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS to SUPPORT FROM

Media Contact: For additional information, Libby Mark or Heather Meltzer at Bow Bridge Communications, LLC, New York City; +1 347-460-5566; [email protected]. March 27, 2018 RESTORATION OF CAPPONI CHAPEL IN CHURCH OF SANTA FELICITA IN FLORENCE, ITALY, COMPLETED THANKS TO SUPPORT FROM FRIENDS OF FLORENCE Yearlong project celebrated with the reopening of the Renaissance architectural masterpiece on March 28, 2018: press conference 10:30 am and public event 6:00 pm Washington, DC....Friends of Florence celebrates the completion of a comprehensive restoration of the Capponi Chapel in the 16th-century church Santa Felicita on March 28, 2018. The restoration project, initiated in March 2017, included all the artworks and decorative elements in the Chapel, including Jacopo Pontormo's majestic altarpiece, a large-scale painting depicting the Deposition from the Cross (1525‒28). Enabled by a major donation to Friends of Florence from Kathe and John Dyson of New York, the project was approved by the Soprintendenza Archeologia Belle Arti e Paesaggio di Firenze, Pistoia, e Prato, entrusted to the restorer Daniele Rossi, and monitored by Daniele Rapino, the Pontormo’s Deposition after restoration. Soprintendenza officer responsible for the Santo Spirito neighborhood. The Capponi Chapel was designed by Filippo Brunelleschi for the Barbadori family around 1422. Lodovico di Gino Capponi, a nobleman and wealthy banker, purchased the chapel in 1525 to serve as his family’s mausoleum. In 1526, Capponi commissioned Capponi Chapel, Church of St. Felicita Pontormo to decorate it. Pontormo is considered one of the most before restoration. innovative and original figures of the first half of the 16th century and the Chapel one of his greatest masterpieces. -

The Exhibit at Palazzo Strozzi “Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino

Issue no. 18 - April 2014 CHAMPIONS OF THE “MODERN MANNER” The exhibit at Palazzo Strozzi “Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. Diverging Paths of Mannerism”, points out the different vocations of the two great artist of the Cinquecento, both trained under Andrea del Sarto. Palazzo Strozzi will be hosting from March 8 to July 20, 2014 a major exhibition entitled Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino. Diverging Paths of Mannerism. The exhibit is devoted to these two painters, the most original and unconventional adepts of the innovative interpretive motif in the season of the Italian Cinquecento named “modern manner” by Vasari. Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino both were born in 1494; Pontormo in Florence and Rosso in nearby Empoli, Tuscany. They trained under Andrea del Sarto. Despite their similarities, the two artists, as the title of the exhibition suggests, exhibited strongly independent artistic approaches. They were “twins”, but hardly identical. An abridgement of the article “I campioni della “maniera moderna” by Antonio Natali - Il Giornale degli Uffizi no. 59, April 2014. Issue no. 18 -April 2014 PONTORMO ACCORDING TO BILL VIOLA The exhibit at Palazzo Strozzi includes American artist Bill Viola’s video installation “The Greeting”, a intensely poetic interpretation of The Visitation by Jacopo Carrucci Through video art and the technique of slow motion, Bill Viola’s richly poetic vision of Pontormo’s painting “Visitazione” brings to the fore the happiness of the two women at their coming together, representing with the same—yet different—poetic sensitivity, the vibrancy achieved by Pontormo, but with a vital, so to speak carnal immediacy of the sense of life, “translated” into the here-and- now of the present. -

He Was More Than a Mannerist - WSJ

9/22/2018 He Was More Than a Mannerist - WSJ DOW JONES, A NEWS CORP COMPANY DJIA 26743.50 0.32% ▲ S&P 500 2929.67 -0.04% ▼ Nasdaq 7986.96 -0.51% ▼ U.S. 10 Yr 032 Yield 3.064% ▼ Crude Oil 70.71 0.55% ▲ This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. To order presentationready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit http://www.djreprints.com. https://www.wsj.com/articles/hewasmorethanamannerist1537614000 ART REVIEW He Was More Than a Mannerist Two Jacopo Pontormo masterpieces at the Morgan Library & Museum provide an opportunity to reassess his work. Pontormo’s ‘Visitation’ (c. 152829) PHOTO: CARMIGNANO, PIEVE DI SAN MICHELE ARCANGELO By Cammy Brothers Sept. 22, 2018 700 a.m. ET New York Jacopo Pontormo (1494-1557), one of the most accomplished and intriguing painters Florence ever produced, has been maligned by history on at least two fronts. First, by the great artist biographer Giorgio Vasari, who recognized Pontormo’s gifts but depicted him as a solitary eccentric who imitated the manner of the German painter and printmaker Albrecht Dürer to a fault. And second, by art historians quick to label him as a “Mannerist,” a term that has often carried negative associations, broadly used to mean excessive artifice and often associated with a period of decline. The term isn’t wrong for Pontormo, but it’s a dead end, explaining away Pontormo’s distinctiveness while sidelining him at the same time. It’s not hard to understand how Pontormo got his Pontormo: Miraculous Encounters reputation. -

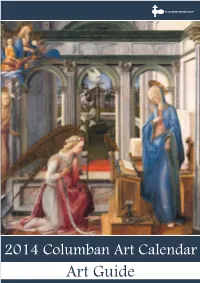

2014 Art Guide

2014 Columban Art Calendar Art Guide Front Cover The Annunciation, Verkuendigung Mariae (detail) Lippi, Fra Filippo (c.1406-1469) In Florence during the late middle ages and Renaissance the story of the Annunciation took on a special meaning. Citizens of this wealthy and pious city dated the beginning of the New Year at the feast day of the Annunciation, March 25th. In this city as elsewhere in Europe, where the cathedral was dedicated to her, the Virgin naturally held a special place in religious life. To emphasize this, Fra Filippo sets the moment of Gabriel’s visit to Mary in stately yet graceful surrounds which recede into unfathomable depths. Unlike Gabriel or Mary, the viewer can detect in the upper left-hand corner the figure of God the Father, who has just released the dove of the Holy Spirit. The dove, a traditional symbol of the third person of the Trinity, descends towards Mary in order to affirm the Trinitarian character of the Incarnation. The angel kneels reverently to deliver astounding news, which Mary accepts with surprising equanimity. Her eyes focus not on her angelic visitor, but rather on the open book before her. Although Luke’s gospel does not describe Mary reading, this detail, derived from apocryphal writings, hints at a profound understanding of Mary’s role in salvation history. Historically Mary almost certainly would not have known how to read. Moreover books like the one we see in Fra Filippo’s painting came into use only in the first centuries CE. Might the artist and the original owner of this painting have greeted the Virgin’s demeanour as a model of complete openness to God’s invitation? The capacity to respond with such inner freedom demanded of Mary and us what Saint Benedict calls “a listening heart”. -

Sight and Touch in the Noli Me Tangere

Chapter 1 Sight and Touch in the Noli me tangere Andrea del Sarto painted his Noli me tangere (Fig. 1) at the age of twenty-four.1 He was young, ambitious, and grappling for the first time with the demands of producing an altarpiece. He had his reputation to consider. He had the spiri- tual function of his picture to think about. And he had his patron’s wishes to address. I begin this chapter by discussing this last category of concern, the complex realities of artistic patronage, as a means of emphasizing the broad- er arguments of my book: the altarpiece commissions that Andrea received were learning opportunities, and his artistic decisions serve as indices of the religious knowledge he acquired in the course of completing his professional endeavors. Throughout this particular endeavor—from his first client consultation to the moment he delivered the Noli me tangere to the Augustinian convent lo- cated just outside the San Gallo gate of Florence—Andrea worked closely with other members of his community. We are able to identify those individuals only in a general sense. Andrea received his commission from the Morelli fam- ily, silk merchants who lived in the Santa Croce quarter of the city and who frequently served in the civic government. They owned the rights to one of the most prestigious chapels in the San Gallo church. It was located close to the chancel, second to the left of the apse.2 This was prime real estate. Renaissance churches were communal structures—always visible, frequently visited. They had a natural hierarchy, dominated by the high altar. -

1 Santo Spirito in Florence: Brunelleschi, the Opera, the Quartiere and the Cantiere Submitted by Rocky Ruggiero to the Universi

Santo Spirito in Florence: Brunelleschi, the Opera, the Quartiere and the Cantiere Submitted by Rocky Ruggiero to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Art History and Visual Culture In March 2017. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. (Signature)…………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Abstract The church of Santo Spirito in Florence is universally accepted as one of the architectural works of Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446). It is nevertheless surprising that contrary to such buildings as San Lorenzo or the Old Sacristy, the church has received relatively little scholarly attention. Most scholarship continues to rely upon the testimony of Brunelleschi’s earliest biographer, Antonio di Tuccio Manetti, to establish an administrative and artistic initiation date for the project in the middle of Brunelleschi’s career, around 1428. Through an exhaustive analysis of the biographer’s account, and subsequent comparison to the extant documentary evidence from the period, I have been able to establish that construction actually began at a considerably later date, around 1440. It is specifically during the two and half decades after Brunelleschi’s death in 1446 that very little is known about the proceedings of the project. A largely unpublished archival source which records the machinations of the Opera (works committee) of Santo Spirito from 1446-1461, sheds considerable light on the progress of construction during this period, as well as on the role of the Opera in the realization of the church. -

The Decoration of the Chapel of Eleonora Di Toledo in the Palazzo Vecchio, Flor

PREFACE The decoration of the Chapel of Eleonora di Toledo in the Palazzo Vecchio, Flor- ence, is a masterpiece of the art of Agnolo Bronzino (1503-1572), painter to the Medici court in Florence in the sixteenth century. Indeed, as the only com- plex ensemble of frescoes and panels he painted, it could be deemed the central work of his career. It is also a primary monument of the religious painting of cinquecento Florence. Just as Bronzino's splendid portraits and erotic allegories established new modes of secular painting that expressed the ideals of mid- sixteenth-century court life, so his innovative chapel paintings transformed tradi- tional biblical narratives and devotional themes according to a new aesthetic. The chapel is also the locus of the emerging personal imagery of its patron, Duke Cosimo I de' Medici (1519-1574), and its decorations adumbrate many of the metaphors of rule, as they have been called, that would be programmatically developed in his more overtly propagandistic later art. There has been no comprehensive, documented, and illustrated study of this central work of Florentine Renaissance art. It was the subject of a short article by Andrea Emiliani (1961) and of my own essays, one on Bronzino's preparatory studies for the decoration (1971) and two others on individual paintings in the chapel (1987, 1989). These were prolegomena to this full-scale study, in which the recently restored frescoes are also illustrated for the first time. X X V 11 I began this book in 1986 at the Getty Center for Art History and the Human- ities, whose staff and director, Kurt W. -

The Renaissance Workshop in Action

The Renaissance Workshop in Action Andrea del Sarto (Italian, 1486–1530) ran the most successful and productive workshop in Florence in the 1510s and 1520s. Moving beyond the graceful harmony and elegance of elders and peers such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, and Fra Bartolommeo, he brought unprecedented naturalism and immediacy to his art through the rough and rustic use of red chalk. This exhibition looks behind the scenes and examines the artist’s entire creative process. The latest technology allows us to see beneath the surface of his paintings in order to appreciate the workshop activity involved. The exhibition also demonstrates studio tricks such as the reuse of drawings and motifs, while highlighting Andrea’s constant dazzling inventiveness. All works in the exhibition are by Andrea del Sarto. This exhibition has been co-organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Frick Collection, New York, in association with the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe, Gallerie degli Uffizi, Florence. We acknowledge the generous support provided by an anonymous donation in memory of Melvin R. Seiden and by the Italian Cultural Institute. The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2014 J. Paul Getty Trust Rendering Reality In this room we focus on Andrea’s much-lauded naturalism and how his powerful drawn studies enabled him to transform everyday people into saints and Madonnas, and smirking children into angels. With the example of The Madonna of the Steps, we see his constant return to life drawing on paper—even after he had started painting—to ensure truth to nature. The J. Paul Getty Museum © 2014 J. -

La Santissima Annunziata Di Firenze-Storia

LA SS. ANNUNZIATA LA STORIA DEL SANTUARIO MARIANO DI FIRENZE di p. Eugenio M. Casalini, osm LE ORIGINI, LE VICENDE, I MONUMENTI ATTRAVERSO I SECOLI. 1. Il Convento e le sue origini. Del convento della SS. Annunziata oggi è visibile, dalla piazza omonima e guardando a sinistra del loggiato della basilica, solo qual tanto del suo insieme che si affaccia, con i sesti acuti di sei bifore tamponate, sopra un caseggiato seicentesco, dove attualmente si apre la monumentale entrata disegnata e costruita da un frate, figlio dello stesso convento, il pittore fra Arsenio Mascagni, nel 1636. Questo è tutto quello che è possibile vedere dell’area occupata nel Cafaggio del Vescovo fin dal secolo XIII dai frati Servi di Maria, l’Ordine fondato secondo la tradizione nel 1233, da sette mercanti fiorentini in onore della Madre di Dio. Frammenti di storia e di archeologia ci assicurano che l’area era già attraversata dal Mugnone, il torrente che, secondo il Villani, scendendo dai poggi di Fiesole, avvolto per Cafaggio, giungeva con le sue anse verso le mura cittadine e le seguiva ad ovest per raggiungere l’Arno (1). In questa zona si dice che si accampasse inutilmente nell’assedio alla città Arrigo IV nel 1082, ed è probabile che in seguito, a memoria della battaglia vinta dai fiorentini proprio nell’angolo in cui sorgerà il convento dei Servi, fosse edificato un oratorio (2). É certo però che alcuni appartenenti alla Societas laica dei Servi di Maria avevano case, corti, poderi in questa zona, e che l’Ordine regolare dei Servi di Maria, nel febbraio del 1250, scendendo dal Monte Senario pose la prima pietra del convento e della chiesa in questa parte della campagna presso le mura cittadine in fundo proprio come ci attestano i documenti (3). -

Santo Spirito Neighborhood Crawl

florence for free free walks and work-arounds for rich italian adventures neighborhood crawl: santo spirito Distance: 2 km (about 1.2 miles) Time: 25 minute walk in total, plus time (up to a day!) for leisurely exploring Cost: $0 Directions: Start out by crossing the Ponte Vecchio. At the bridge’s end, walk straight ahead, looking for a small piazza on your left with a church tucked in the back corner (Sant Felicita). Venture further down Via de’ Guicciardini, past Palazzo Pitti, onto Via Romana, until you reach Via del Campuccio. Turn right, and then make the next right again at Via Caldaie. Walk up to Santo Spirito, head out at the far right of the piazza and turn left on Via Maggio. Walk down to St. Mark’s Church, cross the street and take that right on Via dei Vellutini down to Piazza della Passera. Take Via dello Sprone back out and follow it until you reach Ponte Santa Trinita. Places to see: • Santa Felicita – One of the oldest worship sites in the city, although the current structure mostly dates back to the 18th century. Head here when open in the early morning and venture in under the Vasari Corridor (the arch-shaped interruption in the church’s facade), which also doubled as a private balcony the Medici could worship from without mingling with ordinary plebs. The inside is certainly inspired by the style of Renaissance heavyweight Brunelleschi – the man who solved the riddle of the cathedral dome. He even designed the chapel immediately to the entrance’s right, today known as the Capponi Chapel, which features two masterpieces by Mannerist favorite Jacopo Pontormo. -

Exploring the Path of Del Sarto, Pontormo, and Rosso Fiorentino Thursday, June 11Th Through Monday, June 15Th

- SUMMER 2015 FLORENCE PROGRAM Michelangelo and His Revolutionary Legacy: Exploring the Path of Del Sarto, Pontormo, and Rosso Fiorentino Thursday, June 11th through Monday, June 15th PRELIMINARY ITINERARY (as of January 2015) Program Costs: Program Fee: $4,000 per person (not tax deductible) Charitable Contribution: $2,500 per person (100% tax deductible) Historians: William Wallace, Ph.D. - Barbara Murphy Bryant Distinguished Professor of Art History, Washington University in St. Louis William Cook, Ph.D. - Distinguished Teaching Professor of History, SUNY Geneseo (Emeritus) For additional program and cost details, please see the "Reservation Form," "Terms and Conditions," and "Hotel Lungarno Reservation Form" Thursday, June 11th Afternoon Welcome Lecture by historians Bill Wallace and Bill Cook, followed by private visits to the Medici Chapels. Dinner in an historic landmark of the city. Friday, June 12th Special visit to the church of Santa Felicità to view the extraordinary Pontormo masterpieces, then follow the path across Florence of a selection of frescoes from the Last Supper cycle. The morning will end with a viewing of the Last Supper by Andrea del Sarto in San Salvi. Lunch will be enjoyed on the hillsides of Florence. Later-afternoon private visit to the Bargello Museum, followed by cocktails and dinner in a private palace. Saturday, June 13th Morning departure via fast train to Rome. View Michelangelo's Moses and Risen Christ, followed by lunch. Private visit to the magnificent Palazzo Colonna to view their collection of works by Pontormo, Ridolfo da Ghirlandaio, and other artists. Later afternoon private visit to the Vatican to view the unique masterpieces by Michelangelo in both the Pauline Chapel and the Sistine Chapel, kindly arranged by the Papal offices and the Director of the Vatican Museums. -

Giorgio Vasari at 500: an Homage

Giorgio Vasari at 500: An Homage Liana De Girolami Cheney iorgio Vasari (1511-74), Tuscan painter, architect, art collector and writer, is best known for his Le Vile de' piu eccellenti architetti, Gpittori e scultori italiani, da Cimabue insino a' tempi nostri (Lives if the Most Excellent Architects, Painters and Sculptors if Italy, from Cimabue to the present time).! This first volume published in 1550 was followed in 1568 by an enlarged edition illustrated with woodcuts of artists' portraits. 2 By virtue of this text, Vasari is known as "the first art historian" (Rud 1 and 11)3 since the time of Pliny the Elder's Naturalis Historiae (Natural History, c. 79). It is almost impossible to imagine the history ofItalian art without Vasari, so fundamental is his Lives. It is the first real and autonomous history of art both because of its monumental scope and because of the integration of the individual biographies into a whole. According to his own account, Vasari, as a young man, was an apprentice to Andrea del Sarto, Rosso Fiorentino, and Baccio Bandinelli in Florence. Vasari's career is well documented, the fullest source of information being the autobiography or vita added to the 1568 edition of his Lives (Vasari, Vite, ed. Bettarini and Barocchi 369-413).4 Vasari had an extremely active artistic career, but much of his time was spent as an impresario devising decorations for courtly festivals and similar ephemera. He praised the Medici family for promoting his career from childhood, and much of his work was done for Cosimo I, Duke of Tuscany.