David Robie-Rainbow Warrior.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frank Zelko Research Fellow, GHI

“MAKE IT A GREEN PEACE”: THE HISTORY OF AN INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL ORGANIZATION Frank Zelko Research Fellow, GHI In the early 1970s, the United States Congress’s House Subcommittee on Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation held a series of hearings on the sub- ject of marine mammal protection. Among those who testified were rep- resentatives of America’s oldest and most established wilderness protec- tion groups, such as the Sierra Club, the Audubon Society, and the National Wildlife Federation. Although it was important to ensure that the world’s populations of whales and seals remained as healthy as pos- sible, these organizations argued, they did not support a policy of abso- lute protection. As long as the survival of the species was ensured, they believed, it was legitimate to use its “surplus” members for the benefit of people. In his testimony before the subcommittee, Thomas Kimball of the National Wildlife Federation employed phrases such as “renewable re- sources,” “stewardship,” and “professional wildlife management.” The “harvesting of surplus wildlife populations,” his organization felt, wasan “important management tool if the continuing long-range well-being of an animal population is the ultimate objective.”1 A few years later, a group of environmental protesters off the coast of California came across a fleet of Soviet whaling boats. Using motorized inflatable dinghies, the activists positioned themselves between a whal- er’s harpoon and a fleeing pod of sperm whales, acting as human shields to protect the defenseless giants. Whaling, these activists insisted, was not merely an issue of wildlife preservation or resource stewardship. Rather, it was an unconscionable act of violence perpetrated against a species whose intelligence and sensitivity put them in the same biological cat- egory as human beings. -

Rainbow Warrior Case

1 Rainbow Warrior Case Rainbow Warrior (NEW ZEALAND v. FRANCE) France-New Zealand Arbitration Tribunal. 30 April 1990 (Jiménez de Aréchaga, Chairman; Sir Kenneth Keith and Professor Bredin, Members) SUMMARY: The facts: - In July 1985 a team of French agents sabotaged and sank the Rainbow Warrior, a vessel belonging to Greenpeace International, while it lay in harbour in New Zealand. One member of the crew was killed. Two of the agents, Major Mafart and Captain Prieur, were subsequently arrested in New Zealand and, having pleaded guilty to charges of manslaughter and criminal damage, were sentenced by a New Zealand court to ten years' imprisonment.1 A dispute arose between France, which demanded the release of the two agents, and New Zealand, which claimed compensation for the incident. New Zealand also complained that France was threatening to disrupt New Zealand trade with the European Communities unless the two agents were released. The two countries requested the Secretary-General of the United Nations to mediate and to propose a solution in the form of a ruling, which both Parties agreed in advance to accept. The Secretary-General's ruling, which was given in 1986, required France to pay US $7 million to New Zealand and to undertake not to take certain defined measures injurious to New Zealand trade with the European Communities.2 The ruling also provided that Major Mafart and Captain Prieur were to be released into French custody but were to spend the next three years on an isolated French military base in the Pacific. The two States concluded an agreement in the form of an exchange of letters on 9 July 1986 ("the First Agreement"),3 which provided for the implementation of the ruling. -

Considering the Creation of a Domestic Intelligence Agency in the United States

HOMELAND SECURITY PROGRAM and the INTELLIGENCE POLICY CENTER THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND Homeland Security Program RAND Intelligence Policy Center View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. -

War Criminals at Large

War Criminals at Large By Dr. Daniele Ganser Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, January 09, 2019 Theme: History, Media Disinformation, US NATO War Agenda It is a common misconception that democracies do not start wars of aggression or carry out terrorist attacks. The historical facts for the period from 1945 to today show a completely different reality: time and again, democratic states in Europe and North America have participated in wars of aggression and terrorist attacks in the past 70 years. There are so many cases that I am not able to list all of them here. As examples, I have selected three events from different decades: the illegal attack by the European democracies Britain and France on Egypt in 1956; the terrorist attack by the democracy France onRainbow Warrior, a ship operated by the environmental organization Greenpeace in 1985; and the illegal attack by US President Donald Trump on Syria on April 7, 2017. Because mass media, neither in the European nor the American democracies, openly address and criticize these crimes and because so far the responsible politicians have not been convicted by a court, a stubborn misconception persists in the populations of these aggressor states that democracies never start wars and also never use terror as a political instrument. But the three examples mentioned show clearly: Democracies, members of the NATO military alliance and with a veto power in the UN Security Council to protect themselves from condemnation, have repeatedly attacked other countries. This is illegal. For the UN Charter of 1945, Article 2 (4), clearly states: All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force..[..] The Charter only allows the use of force if an attacked state defends itself or if the United Nations Security Council has approved the military strike. -

Environmental Organizations Treaties

74 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS Headquarters: Parkring 8, POB 995, A-1011 Vienna, Austria. flagship, Rainbow Warrior, while it was in Auckland Harbour, Website: http://www.ofid.org New Zealand. Email: [email protected] Mission. Greenpeace is an independent global environmental Director-General: Suleiman Jasir al-Herbish (Saudi Arabia). organization that aims to secure a planet ‘that is ecologically healthy and able to nurture life in all its diversity’. It campaigns to: prevent pollution and abuse of the Earth’sland,oceans,air and fresh water; end all nuclear threats; and promote peace, global Environmental Organizations disarmament and non-violence. Organization. Greenpeace International has its headquarters in Friends of the Earth International Amsterdam in the Netherlands, from where it co-ordinates worldwide campaigns and monitors and advises 28 national and Origin. Friends of the Earth was founded in 1971 by a network of regional offices. These provide a presence in over 40 countries. environmental activists from France, Sweden, the UK and the USA. Financial contributions from governments, political parties and Mission. The organization aims to ‘collectively ensure environ- commercial organizations are not accepted. Funding is provided mental and social justice, human dignity, and respect for human by individual supporters and foundation grants. In the 18 months rights and peoples’ rights so as to ensure sustainable societies’. to Jan. 2009, 2·9m. people took out or renewed financial membership. Organization. Friends of the Earth International comprises 74 Headquarters: Ottho Heldringstraat 5, 1066 AZ Amsterdam, national member groups, with a combined membership of Netherlands. individuals exceeding 2m. around the world in some 5,000 local Website: http://www.greenpeace.org activist groups. -

![Eylemcilerden Fransa'ya Nükleer Çağrısı Enerji [D]Evrimi](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2417/eylemcilerden-fransaya-n%C3%BCkleer-%C3%A7a%C4%9Fr%C4%B1s%C4%B1-enerji-d-evrimi-1172417.webp)

Eylemcilerden Fransa'ya Nükleer Çağrısı Enerji [D]Evrimi

SAYI #92 greenpeace.org.tr Özel dosya 30 yıl geçti... Eylemcilerden Gökkuşağını Fransa’ya nükleer batıramazsınız! çağrısı Enerji [D]evrimi TEMMUZ 2015 / 25 TL TEMMUZ 2015 / 25 İçindekiler Gökkuşağını GREENPEACE BÜLTEN batıramazsınız! Yerel Süreli Yayın İlk Rainbow Warrior gemimizin barışçıl bir İmtiyaz Sahibi protesto öncesi Fransız Greenpeace Akdeniz Gizli Servisi tarafından Basım ve Tanıtım bombalanmasının ve Hizmetleri Ltd. Şti. olayda fotoğrafçı Fernando Dilek Aldemir Pereira’nın hayatını kaybetmesinin üzerinden Genel Yayın Merkezi 30 yıl geçti... Asmalı Mescit Mh. Kallavi Sk. No: 1 Kat: 5 Beyoğlu I İstanbul Tel: +90 212 292 76 19 04 Faks: +90 212 292 76 22 Fransız Gizli Servisi bir Genel Yayın Yönetmeni gemiyi batırabileceğine Dilek Aldemir inanmakta haklı olsa da, milyonlarca insanın Sorumlu Yazı İşleri Müdürü cesaretini kırabileceği konusunda yanılıyordu. Ece Ünver Bir Greenpeace Fotoğraflar: © Elsa Palito / Greenpeace destekçisinin çok güzel Editör bir şekilde ifade ettiği gibi: Çağrı Özütürk Gökkuşağını batıramazsınız! Baskı Enerji [D]evrimi raporu Yasin Gedik Greenpeace 10 yayınlandı Printworld Matbaa San. Tic. A.Ş. Türkiye’nin enerji ihtiyacını Grafik Tasarım ve Uygulama karşılamak için kömür ve eylemcilerinden Jargon İstanbul nükleere ihtiyacı olmadığını ortaya koyan yeni Enerji [D]evrimi raporunu Dağıtım yayınladık. Avrupa Birliği PTT Fransa’ya çağrı Yenilenebilir Enerji Konseyi ile ortaklaşa hazırladığımız rapor, Kemal Derviş’in 25 Greenpeace eylemcisi, Fransa önsözü ile sunuluyor. hükümetinin pahalı ve geleceği olmayan nükleer santraller yerine, yenilenebilir enerjilere yatırım yapması için Maliye Bakanlığı’nın girişini kapatarak eylem Yeni Enerji [D]evrimi raporu gerçekleştirdi. Eylemciler girişin önünde Türkiye’nin 2023 yılına kadar yenilenebilir enerji “Nükleer iflas ettirir, yatırımları durdur,” üretimini yaklaşık iki katına yazan bir pankart açtı. -

The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior: Responses to an International Act of Terrorism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NECTAR Journal of Postcolonial Cultures and Societies ISSN No. 1948-1845 (Print); 1948-1853 (Electronic) The sinking of the rainbow warrior: Responses to an international act of terrorism Janet Wilson Introduction: the Rainbow Warrior Affair The Rainbow Warrior affair, an act of sabotage against the flagship of the Greenpeace fleet, the Rainbow Warrior, when berthed at Marsden wharf in Auckland harbour on 10th July 1985, dramatised in unprecedented ways issues of neo-imperialism, national security, eco-politics and postcolonialism in New Zealand. The bombing of the yacht by French secret service agents effectively prevented its participation in a Nuclear Free Pacific campaign in which it was to have headed the Pacific Fleet Flotilla to Moruroa atoll protesting French nuclear testing. Outrage was compounded by tragedy: the vessel’s Portuguese photographer, Fernando Pereira, went back on board to get his camera after the first detonation and was drowned in his cabin following the second one. The evidence of French Secret Service (Direction Generale de la Securite Exterieure or DGSE) involvement which sensationally emerged in the following months, not only enhanced New Zealand’s status as a small nation and wrongful victim of French neo-colonial ambitions, it dramatically magnified Greenpeace’s role as coordinator of New Zealand and Pacific resistance to French bomb-testing. The stand-off in New Zealand –French political relations for almost a decade until French bomb testing in the Pacific ceased in 1995 notwithstanding, this act of terrorism when reviewed after almost 25 years in the context of New Zealand’s strategic and political negotiations of the 1980s, offers a focus for considering the changing composition of national and regional postcolonial alliances during Cold War politics. -

Nuclear Flashback Part

Workers in the Cannikin shaft, Amchitka Island, 1971. (U.S. Department ofEnergy photograph) A quarter-century of Greenpeace nuclear criticism culminates in this report. Greenpeace now spins this work off in two directions: Norm Buske Nuclear-Weapons-Free America 785 20th Street, #3 Boulder, CO 80302 303.415.1504 phonelfax [email protected] Pamela K. Miller Alaska Community Action onToxics 135 Christensen Drive Anchorage, AK 99501 907.222.n14 phone 907.222.n15fax PART TWO : acat @akcf.org TheThreat of the U.S. Nuclear Complex Nuclear-Weapons-Free America aims A report confirming radioactive leakage into the Bering Sea to end U.S. deployment of weapons of from the world's largest underground nuclear explosion mass destruction with their attendant risks of catastrophic planetary losses. Authors: Alaska Community Action of Toxics Norm Buske, Nuclear-Weapons-Free America seeks to protect environmental and Pamela K. Miller, Alaska Community Action on human health by eliminating sources of Toxics toxic and radioactive pollution. February 1998 Table of Contents Summary: Chronicle of a Department of Energy Cover-Up at Amchitka .............................................03 Background: Amchitka Nuclear Blasts and the Public Storm of Protest .............................................04 . Conclusions from the 1997 Sampling Program ........................... ;................. 05 The Truth is Leaking Out: Independent Monitoring of Radiation Leakage at U.S. and French Nuclear Sites .............................................. 07 The Cannikin nuclearbomb is lowered Nuclear Flashback II: Follow-Up DOE into the Earth. Amchitka Island, 1971. Study with Public Oversight .............................................09 Return to Ground Zero: The 1997 ATAG FieldWork ..............................................12 The 1997 ATAG Study Results . The authors wish to thank: . ............................................. 19 Jay Stange, editing and graphics Karen Button, cover design DOE Lab Failures and Delays: Devil in Bev Aleck the Details? Dr. -

Operación Satanique, Un Claro Ejemplo De Operación Encubierta Fallida”

“OPERACIÓN SATANIQUE, UN CLARO EJEMPLO DE OPERACIÓN ENCUBIERTA FALLIDA” Juan Antonio Martínez Sánchez. Ministerio de Defensa. [email protected] Capitán Psicólogo (CMS). Licenciado en Psicología; Máster en Paz, Seguridad y Defensa; Máster Oficial en Sistema Penal, Criminalidad y Políticas de Seguridad y Especialista Universitario en Servicios de Inteligencia. Actualmente realiza estudios de doctorado en el Programa “Ciencias Sociales y Jurídicas” de la Universidad de Cádiz. Autor de varias publicaciones relacionadas con la Psicología Militar Operativa y los Servicios de Inteligencia. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7696-5023 Resumen La presente comunicación analiza la operación Satanique, una operación encubierta orquestada por el gobierno francés y ejecutada por agentes de la Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure (DGSE) en 1985 en Auckland (Nueva Zelanda). Dicha operación consistió en el sabotaje y hundimiento del buque de Greenpeace, Rainbow Warrior, y tuvo graves consecuencias, tanto a nivel nacional como internacional, provocando uno de los mayores escándalos políticos del siglo XX. Al abordar los pormenores de dicha operación nos centraremos en una serie de aspectos claves, como sus antecedentes, en lo que se refiere a su gestación y planificación; su ejecución o puesta en marcha, como claro ejemplo de operación encubierta; los detalles de la investigación realizada por la policía neozelandesa, decisiva para desvelar la implicación del Gobierno francés; y las consecuencias de dicho acto. Palabras claves: operaciones encubiertas, operación Satanique, DGSE, Greenpeace, Rainbow Warrior. Abstract This paper analyzes the operation Satanique, a covert operation orchestrated by the French government and carried out by agents of the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure (DGSE) in 1985, in Auckland (New Zealand). -

Greenpeace International Financial Statements 2014

GREENPEACE INTERNATIONAL AND RELATED ENTITIES COMBINED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Year ended 31 December 2014 Contents Page: 2. Board report Combined Financial Statements 5. Combined Statement of Financial Position 6. Combined Statement of Comprehensive Income for the year 7. Combined Statement of Changes of Equity for the year 8. Combined Statement of Cash Flows for the year 9. Notes to the Combined Financial Statements Stichting Greenpeace Council Financial Statements 32. Stichting Greenpeace Council Statement of Financial Position 33. Stichting Greenpeace Council Statement of Comprehensive Income for the year 34. Stichting Greenpeace Council Statement of Changes of Equity for the year 35. Stichting Greenpeace Council Notes to the Financial Statements Other information 45. Appropriation of result 46. Independent auditors’ report 1 GREENPEACE INTERNATIONAL & RELATED ENTITIES Board report 2014 Board Report The Board of Stichting Greenpeace Council and related entities hereby presents its financial statements for the year ended on 31 December 2014. General Information These financial statements refer to Greenpeace International (GPI) and related entities only. Greenpeace International is an independent, campaigning organisation which uses non-violent, creative confrontation to expose global environmental problems, and to promote the solutions which are essential to a green and peaceful future. Greenpeace's goal is to ensure the ability of the earth to nurture life in all its diversity. Greenpeace International monitors the organisational development of 26 independent Greenpeace organisations, oversees the development and maintenance of our the Greenpeace ships, enables global campaigns, and monitors compliance with core policies. The 26 independent Greenpeace National & Regional organisations are based across the globe. The National & Regional Organisations (NROs) are independent organisations who share common values and campaign together to expose and resolve global environmental problems. -

Issue No. 113, October-November, 1985

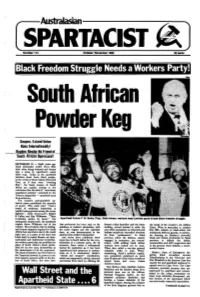

Number 113 October I November 1985 - 30centa Black Freedom Struggle "eeds a Workers Party! I I Deepen, Extend Union Bans Internationally! __"J!~~f!I~~!H~!~! ft!!l!J!!~'!!f, South African Oppressed'! SEPTEMBER 30 - Eight years ago black nationalist leader Steve Bao died, after being tortured and beaten into a coma by apartheid's racist killer cops. Today as the apartheid butchers shoot down black people, in the words of black bishop Desmond Tutu, as if they were "swatting flies", the black masses of South Africa are rapidly coming to the conclusion that the kind of "nonviolent negotiated solution" preached by the Tutus is impossible - apartheid must be overthrown. The massive anti-apartheid up heaval poses pointblank the question of power: Who shall rule? "Tutu's brand of moderate leadership is rapidly losing ground among the street fighters", wrote Newswee/c's Robert B Cullen and Ray Wilkinson. "Their revolution awaits its Lenin. " For Apartheid Fuhrer P W Bothe (Top). Gold mlneri: workers need leninist party to lead black freedom struggle. stating this simple truth, the apartheid regime threw W'tlkinson out of the that proletariat has been kept on the former a fake franchise and the latter the backs of the country's six million country. But precisely what is lacking, sidelines in isolated skirmishes with nothing, served instead to unite the Zulus. What is necessary to combat and is more urgently required in South' the racist regime and the capitalist non-white population as coloureds and this fifth column is trade-union led Africa than anywhere else in the world baas, as was' demonstrated in the Indians massively boycotted elections multiracial defence guards, in particu· right now, is a party of the kind that aborted mine strike in September. -

France in the South Pacific Power and Politics

France in the South Pacific Power and Politics France in the South Pacific Power and Politics Denise Fisher Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fisher, Denise, author. Title: France in the South Pacific : power and politics / Denise Fisher. ISBN: 9781922144942 (paperback) 9781922144959 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: France--Foreign relations--Oceania. Oceania--Foreign relations--France. France--Foreign relations--New Caledonia. New Caledonia--Foreign relations--France. Dewey Number: 327.44095 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2013 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii List of maps, figures and tables . ix Glossary and acronyms . xi Maps . xix Introduction . 1 Part I — France in the Pacific to the 1990s 1. The French Pacific presence to World War II . 13 2. France manages independence demands and nuclear testing 1945–1990s . 47 3 . Regional diplomatic offensive 1980s–1990s . 89 Part II — France in the Pacific: 1990s to present 4. New Caledonia: Implementation of the Noumea Accord and political evolution from 1998 . 99 5. French Polynesia: Autonomy or independence? . 179 6. France’s engagement in the region from the 1990s: France, its collectivities, the European Union and the region .