Radioactivity Under the Sand – Analysis with Regard to the Treaty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frank Zelko Research Fellow, GHI

“MAKE IT A GREEN PEACE”: THE HISTORY OF AN INTERNATIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL ORGANIZATION Frank Zelko Research Fellow, GHI In the early 1970s, the United States Congress’s House Subcommittee on Fisheries and Wildlife Conservation held a series of hearings on the sub- ject of marine mammal protection. Among those who testified were rep- resentatives of America’s oldest and most established wilderness protec- tion groups, such as the Sierra Club, the Audubon Society, and the National Wildlife Federation. Although it was important to ensure that the world’s populations of whales and seals remained as healthy as pos- sible, these organizations argued, they did not support a policy of abso- lute protection. As long as the survival of the species was ensured, they believed, it was legitimate to use its “surplus” members for the benefit of people. In his testimony before the subcommittee, Thomas Kimball of the National Wildlife Federation employed phrases such as “renewable re- sources,” “stewardship,” and “professional wildlife management.” The “harvesting of surplus wildlife populations,” his organization felt, wasan “important management tool if the continuing long-range well-being of an animal population is the ultimate objective.”1 A few years later, a group of environmental protesters off the coast of California came across a fleet of Soviet whaling boats. Using motorized inflatable dinghies, the activists positioned themselves between a whal- er’s harpoon and a fleeing pod of sperm whales, acting as human shields to protect the defenseless giants. Whaling, these activists insisted, was not merely an issue of wildlife preservation or resource stewardship. Rather, it was an unconscionable act of violence perpetrated against a species whose intelligence and sensitivity put them in the same biological cat- egory as human beings. -

From Wilderness to the Toxic Environment: Health in American Environmental Politics, 1945-Present

From Wilderness to the Toxic Environment: Health in American Environmental Politics, 1945-Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Thomson, Jennifer Christine. 2013. From Wilderness to the Toxic Environment: Health in American Environmental Politics, 1945- Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11125030 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA From Wilderness to the Toxic Environment: Health in American Environmental Politics, 1945-Present A dissertation presented by Jennifer Christine Thomson to The Department of the History of Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Science Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2013 @ 2013 Jennifer Christine Thomson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Charles Rosenberg Jennifer Christine Thomson From Wilderness to the Toxic Environment: Health in American Environmental Politics, 1945-Present Abstract This dissertation joins the history of science and medicine with environmental history to explore the language of health in environmental politics. Today, in government policy briefs and mission statements of environmental non-profits, newspaper editorials and activist journals, claims about the health of the planet and its human and non-human inhabitants abound. Yet despite this rhetorical ubiquity, modern environmental politics are ideologically and organizationally fractured along the themes of whose health is at stake and how that health should be protected. -

The Electoral Consequences of Nuclear Fallout: Evidence from Chernobyl

Working Paper 2020:23 Department of Economics School of Economics and Management The Electoral Consequences of Nuclear Fallout: Evidence from Chernobyl Adrian Mehic November 2020 The electoral consequences of nuclear fallout: Evidence from Chernobyl Adrian Mehic ∗ This version: November 19, 2020 Abstract What are the political effects of a nuclear accident? Following the 1986 Chernobyl disaster, environmentalist parties were elected to parliaments in several nations. This paper uses Chernobyl as a natural experiment creating variation in radioactive fallout exposure over Sweden. I match municipality-level data on cesium ground contamination with election results for the anti-nuclear Green Party, which was elected to parliament in 1988. After adjusting for pre-Chernobyl views on nuclear power, the results show that voters in high-fallout areas were more likely to vote for the Greens. Additionally, using the exponential decay property of radioactive isotopes, I show a persistent, long-term effect of fallout on the green vote. However, the Chernobyl-related premium in the green vote has decreased substantially since the 1980s. Detailed individual-level survey data further suggests that the results are driven by a gradually decreasing resistance to nuclear energy in fallout-affected municipalities. JEL classification codes: D72, P16, Q48, Q53 Keywords: Chernobyl; pollution; voting ∗Department of Economics, Lund University, Sweden. This work has benefited from discus- sions with Andreas Bergh, Matz Dahlberg, Karin Edmark, Henrik Ekengren Oscarsson, Emelie Theobald, and Joakim Westerlund, as well as numerous seminar participants. 1. Introduction Nuclear energy is a widely debated topic. Advocates of nuclear power argue that it provides high power output combined with virtually zero emissions. -

Andrew S. Burrows, Robert S. Norris William M

0?1' ¥t Andrew S. Burrows, Robert S. Norris William M. Arkin, and Thomas B. Cochran GREENPKACZ Damocles 28 rue des Petites Ecuries B.P. 1027 75010 Paris 6920 1 Lyon Cedex 01 Tel. (1) 47 70 46 89 TO. 78 36 93 03 no 3 - septembre 1989 no 3809 - maWaoOt 1989 Directeur de publication, Philippe Lequenne CCP lyon 3305 96 S CPPAP no en cours Directeur de publication, Palrtee Bouveret CPPAP no6701 0 Composition/Maquette : P. Bouverei Imprime sur papier blanchi sans chlore par Atelier 26 / Tel. 75 85 51 00 Depot legal S date de parution Avant-propos a ['edition fran~aise La traduction fran~aisede cette etude sur les essais nucleaires fran~aisentre dans Ie cadre d'une carnpagne mondiale de GREENPEACEpour la denuclearisation du Pacifique. Les chercheurs americains du NRDC sont parvenus a percer Ie secret qui couvre en France tout ce qui touche au nucleaire militaire. Ainsi, la France : - a effectub 172 essais nucleaires de 1960 a 1988. soil environ 10 % du nornbre total d'essais effectues depuis 1945 ; - doit effectuer 20 essais pour la rnise au point d'une t6te d'ame nuclhaire ; - effectual! 8 essais annuels depuis quelques annees et ces essais ont permis la mise au point de la bombe a neutrons des 1985 ; - a produit, depuis 1963, environ 800 tetes nuclbaires et pres de 500 sont actusllement deployees ; - a effectue pks de 110 essais souterrains a Mururoa. Les degats causes a I'atatI sont tres importants. La rbcente decision oflicielle du regroupement des essais en une seule carnpagne de tirs annuelle n'a probablement pas ete prise uniquernent pour des imperatifs econamiques ou de conjoncture internationale. -

SPECIAL PUBLICATION 6 the Effects of Marine Debris Caused by the Great Japan Tsunami of 2011

PICES SPECIAL PUBLICATION 6 The Effects of Marine Debris Caused by the Great Japan Tsunami of 2011 Editors: Cathryn Clarke Murray, Thomas W. Therriault, Hideaki Maki, and Nancy Wallace Authors: Stephen Ambagis, Rebecca Barnard, Alexander Bychkov, Deborah A. Carlton, James T. Carlton, Miguel Castrence, Andrew Chang, John W. Chapman, Anne Chung, Kristine Davidson, Ruth DiMaria, Jonathan B. Geller, Reva Gillman, Jan Hafner, Gayle I. Hansen, Takeaki Hanyuda, Stacey Havard, Hirofumi Hinata, Vanessa Hodes, Atsuhiko Isobe, Shin’ichiro Kako, Masafumi Kamachi, Tomoya Kataoka, Hisatsugu Kato, Hiroshi Kawai, Erica Keppel, Kristen Larson, Lauran Liggan, Sandra Lindstrom, Sherry Lippiatt, Katrina Lohan, Amy MacFadyen, Hideaki Maki, Michelle Marraffini, Nikolai Maximenko, Megan I. McCuller, Amber Meadows, Jessica A. Miller, Kirsten Moy, Cathryn Clarke Murray, Brian Neilson, Jocelyn C. Nelson, Katherine Newcomer, Michio Otani, Gregory M. Ruiz, Danielle Scriven, Brian P. Steves, Thomas W. Therriault, Brianna Tracy, Nancy C. Treneman, Nancy Wallace, and Taichi Yonezawa. Technical Editor: Rosalie Rutka Please cite this publication as: The views expressed in this volume are those of the participating scientists. Contributions were edited for Clarke Murray, C., Therriault, T.W., Maki, H., and Wallace, N. brevity, relevance, language, and style and any errors that [Eds.] 2019. The Effects of Marine Debris Caused by the were introduced were done so inadvertently. Great Japan Tsunami of 2011, PICES Special Publication 6, 278 pp. Published by: Project Designer: North Pacific Marine Science Organization (PICES) Lori Waters, Waters Biomedical Communications c/o Institute of Ocean Sciences Victoria, BC, Canada P.O. Box 6000, Sidney, BC, Canada V8L 4B2 Feedback: www.pices.int Comments on this volume are welcome and can be sent This publication is based on a report submitted to the via email to: [email protected] Ministry of the Environment, Government of Japan, in June 2017. -

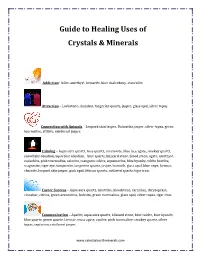

Guide to Healing Uses of Crystals & Minerals

Guide to Healing Uses of Crystals & Minerals Addiction- Iolite, amethyst, hematite, blue chalcedony, staurolite. Attraction – Lodestone, cinnabar, tangerine quartz, jasper, glass opal, silver topaz. Connection with Animals – Leopard skin Jasper, Dalmatian jasper, silver topaz, green tourmaline, stilbite, rainforest jasper. Calming – Aqua aura quartz, rose quartz, amazonite, blue lace agate, smokey quartz, snowflake obsidian, aqua blue obsidian, blue quartz, blizzard stone, blood stone, agate, amethyst, malachite, pink tourmaline, selenite, mangano calcite, aquamarine, blue kyanite, white howlite, magnesite, tiger eye, turquonite, tangerine quartz, jasper, bismuth, glass opal, blue onyx, larimar, charoite, leopard skin jasper, pink opal, lithium quartz, rutilated quartz, tiger iron. Career Success – Aqua aura quartz, ametrine, bloodstone, carnelian, chrysoprase, cinnabar, citrine, green aventurine, fuchsite, green tourmaline, glass opal, silver topaz, tiger iron. Communication – Apatite, aqua aura quartz, blizzard stone, blue calcite, blue kyanite, blue quartz, green quartz, larimar, moss agate, opalite, pink tourmaline, smokey quartz, silver topaz, septarian, rainforest jasper. www.celestialearthminerals.com Creativity – Ametrine, azurite, agatized coral, chiastolite, chrysocolla, black amethyst, carnelian, fluorite, green aventurine, fire agate, moonstone, celestite, black obsidian, sodalite, cat’s eye, larimar, rhodochrosite, magnesite, orange calcite, ruby, pink opal, blue chalcedony, abalone shell, silver topaz, green tourmaline, -

NIOSH Mining Program Strategic Plan

NIOSH Mining Program Strategic Plan 2019–2023 A roadmap for reducing and eliminating illnesses, injuries, and fatalities for the mining workforce Letter from the Associate Director for Mining The Office of Mine Safety and Health Research (OMSHR) is an Office within the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) that is tasked with developing knowledge and technology advances for ensuring the well-being of mine workers. We perform this important work in close collaboration with many stakeholders including mine workers, industry, labor organizations, trade associations, academia, government, and other public and private organizations as well as the occupational health and safety community at large. These relationships ensure that the NIOSH Mining Program focuses taxpayer dollars on solving the highest priority mine worker health and safety challenges. In order to inform our stakeholders and the public about our current and future plans, we have written an updated five-year Strategic Plan (2019–2023). As in the previous version of the Plan, we remain stakeholder-driven with a mining subsector approach that includes coal, crushed stone, sand and gravel, metal, and industrial minerals. This approach allows us to focus our program to better address the health and safety challenges that are unique to each subsector. Our research is driven by both our mission—“To eliminate mining fatalities, injuries, and illnesses through relevant research and impactful solutions”—and our core values of relevance, impact, innovation, integrity, collaboration, and excellence. With this focus on our mission and our core values, we are dedicated to achieving our overall vision of safe mines and healthy workers. -

The Sinking of the Rainbow Warrior: Responses to an International Act of Terrorism

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NECTAR Journal of Postcolonial Cultures and Societies ISSN No. 1948-1845 (Print); 1948-1853 (Electronic) The sinking of the rainbow warrior: Responses to an international act of terrorism Janet Wilson Introduction: the Rainbow Warrior Affair The Rainbow Warrior affair, an act of sabotage against the flagship of the Greenpeace fleet, the Rainbow Warrior, when berthed at Marsden wharf in Auckland harbour on 10th July 1985, dramatised in unprecedented ways issues of neo-imperialism, national security, eco-politics and postcolonialism in New Zealand. The bombing of the yacht by French secret service agents effectively prevented its participation in a Nuclear Free Pacific campaign in which it was to have headed the Pacific Fleet Flotilla to Moruroa atoll protesting French nuclear testing. Outrage was compounded by tragedy: the vessel’s Portuguese photographer, Fernando Pereira, went back on board to get his camera after the first detonation and was drowned in his cabin following the second one. The evidence of French Secret Service (Direction Generale de la Securite Exterieure or DGSE) involvement which sensationally emerged in the following months, not only enhanced New Zealand’s status as a small nation and wrongful victim of French neo-colonial ambitions, it dramatically magnified Greenpeace’s role as coordinator of New Zealand and Pacific resistance to French bomb-testing. The stand-off in New Zealand –French political relations for almost a decade until French bomb testing in the Pacific ceased in 1995 notwithstanding, this act of terrorism when reviewed after almost 25 years in the context of New Zealand’s strategic and political negotiations of the 1980s, offers a focus for considering the changing composition of national and regional postcolonial alliances during Cold War politics. -

Arctic Pollution 2009 Arctic Pollution 2009

Arctic Pollution 2009 Arctic Pollution Arctic Pollution 2009 Arctic Monitoring and Assessment Programme (AMAP) ISBN 978-82-7971-050-9 Arctic Pollution 2009 Contents Preface .................................................................................................................................................... iii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................. v I. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Climate patterns affect contaminant transport II. Persistent Organic Pollutants ...................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction Brominated flame retardants Fluorinated compounds Polychlorinated naphthalenes (PCNs) High-volume chemicals with POP characteristics Endosulfan and other current use pesticides Legacy POPs Effects in Arctic wildlife Chapter summary III. International treaties and actions to limit the use and emission of POPs and heavy metals .................... 34 IV. Contaminants and Human Health ............................................................................................................. 37 Factors influencing human exposure to contaminants Food, diet, nutrition, and contaminants Levels and trends Contaminants and metabolism Effects and public health Demographic data show different patterns for many -

Moruroa, La Bombe Et Nous a Été Conçu Par L a D É L É G a Ti O N P O U R Le Suivi Des Conséquences Des Essais Nucléaires

Bruno BARRILLOT Heinui LE CAILL DSCEN Délégation pour le suivi des conséquences des essais nucléaires “Dans le monde tel qu’il devient, Tahiti jusqu’à présent lointaine, isolée au milieu des mers, Tahiti tout à coup voit s’ouvrir un rôle important, un rôle nouveau sur le globe terrestre (...) Tahiti peut être demain un refuge et un centre d’action pour la civilisation toute entière.” Général de Gaulle à Papeete, 1956 SOMMAIRE p.2 Hiroshima, 1945 p.4 Les essais nucléaires français p.6 Les chantiers du CEP p.8 Le CEP dans les îles p.10 Le 2 juillet 1966, une bombe comment ça marche ? p.16 Le courageux discours du député John Teariki p.18 Histoire de Tureia (1967 – 1968) p.22 La contestation p.24 Bouleversement économique et social de la Polynésie p.26 Les essais souterrains à Moruroa p.28 1995 : La reprise des essais Hiroshima, 1945 Dans la première moitié du XXe siècle, de grands savants, comme Albert Einstein, Pierre et Marie Curie découvrent la radioactivité et ses applications. Au cours de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale, les États-Unis mettent en place un grand programme secret pour transformer l’énorme puissance explosive de l’atome en arme de guerre. Des milliers de scientifiques et de militaires furent engagés dans le cadre du « Manhattan Project » pour mettre au point la bombe atomique. Albert Einstein Pierre et Marie Curie 2 En 1945, pour mettre un terme à la guerre contre le Japon, le prési- dent américain Harry Truman décida de larguer une première bombe atomique nommée « Little Boy » sur la ville d’Hiroshima le 6 août et une seconde nommée « Fat Man » sur la ville de Nagasaki le 9 août. -

[email protected] Available Pacific Flights by Country Updated 9 March 2021

Please note, although we endeavour to provide you with the most up to date information derived from various third parties an d sources, we cannot be held accountable for any inaccuracies or changes to this information. Inclusion of company information in this matrix does no t imply any business relationship between the supplier and WFP / Logistics Cluster, and is used solely as a determinant of services, and capacitie s. Logistics Cluster /WFP maintain complete impartiality and are not in a position to endorse, comment on any company's suitability as a reputable serv ice provider. If you have any updates to share, please email them to: [email protected] Available Pacific Flights by Country Updated 9 March 2021 Region Pacific Island Country Served Airline Type of flight Origin Destination Frequency Dep Day Comments South Pacific American Samoa - South Pacific Cook Islands Air New Zealand Passenger / Cargo Auckland Rarotonga 2 per week Wed & Sat Available until 27 March 2021. South Pacific Cook Islands Air New Zealand Passenger / Cargo Rarotonga Auckland 2 per week Wed & Sat Available until 27 March 2021. South Pacific Fiji Air New Zealand Passenger Auckland Nadi 1 per week TBC Available until 27 March 2021. South Pacific Fiji Fiji Airways Cargo Auckland Nadi 1 per week Fri Fiji Airways will operate the repatriation flights allowing citizens as South Pacific Fiji Fiji Airways Passenger Auckland Nadi 1 per 2 weeks Thu well as approved non-citizens to travel to their respective destinations until 29 April 2021. Fiji Airways will operate the following repatriation flights allowing citizens as well as approved non-citizens to travel South Pacific Fiji Fiji Airways Passenger Brisbane Nadi 1 per 2 weeks Fri to their respective destinations until 23 April as indicated except on 12 & 26 February and with an extra flight on Monday 22 February. -

[email protected] Available Pacific Flights by Country Updated 13 October 2020

Please note, although we endeavour to provide you with the most up to date information derived from various third parties and sources, we cannot be held accountable for any inaccuracies or changes to this information. Inclusion of company information in this matrix does not imply any business relationship between the supplier and WFP / Logistics Cluster, and is used solely as a determinant of services, and capacities. Logistics Cluster /WFP maintain complete impartiality and are not in a position to endorse, comment on any company's suitability as a reputable service provider. If you have any updates to share, please email them to: [email protected] Available Pacific Flights by Country Updated 13 October 2020 Region Pacific Island Country Served Airline Type of flight Origin Destination Frequency Dep Day Comments This flight info is based on the weekly South Pacific American Samoa Asia Pacific Airlines Cargo Honolulu Pagopago 1 per week Fri schedule last published by Asia Pacific on 1 August 2020. This flight info is based on the weekly South Pacific American Samoa Asia Pacific Airlines Cargo Pagopago Honolulu 1 per week Fri schedule last published by Asia Pacific on 1 August 2020. South Pacific Cook Islands Air New Zealand Passenger / Cargo Auckland Rarotonga 1 per week TBC Available until 24 October 2020. South Pacific Cook Islands Air New Zealand Passenger / Cargo Rarotonga Auckland 1 per week TBC Available until 24 October 2020. Available from 5 September to 7 South Pacific Cook Islands Air Tahiti Passenger Papeete Rarotonga 1 per week Sat November 2020. South Pacific Fiji Air New Zealand Passenger Auckland Nadi 1 per week TBC Available until 24 October 2020.