Report Lingering Shadows Communal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rail Infrastructure Development Plan and Planning for International Railway Connectivity in Myanmar

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT AND COMMUNICATIONS MYANMA RAILWAYS Expert Group Meeting on the Use of New Technologies for Facilitation of International Railway Transport 9-12 December, 2019 Rail Infrastructure Development Plan and Planning for International Railway Connectivity in Myanmar Ba Myint Managing Director Myanma Railways Ministry of Transport and Communications MYANMAR Contents . Brief Introduction on situation of Transport Infrastructure in Myanmar . Formulation of National Transport Master Plan . Preparation for the National Logistics Master Plan Study (MYL‐Plan) . Status of Myanma Railways and Current Rail Infrastructure Development Projects . Planning for International Railway Connectivity in Myanmar 2 Brief Introduction on situation of Transport Infrastructure in Myanmar Myanma’s Profile . Population – 54.283 Million(March,2018) India . Area ‐676,578 Km² China . Coastal Line ‐ 2800 km . Road Length ‐ approximately 150,000 km . Railways Route Length ‐ 6110.5 Km . GDP per Capita – 1285 USD in 2018 Current Status Lao . Myanmar’s Transport system lags behind ASEAN . 60% of highways and rail lines in poor condition Thailand . 20 million People without basic road access . $45‐60 Billion investments needs (2016‐ 2030) Reduce transport costs by 30% Raise GDP by 13% Provide basic road access to 10 million people and save People’s lives on the roads. 4 Notable Geographical Feature of MYANMAR India China Bangaladesh Lao Thailand . As land ‐ bridge between South Asia and Southeast Asia as well as with China . Steep and long mountain ranges hamper the development of transport links with neighbors. 5 Notable Geographical Feature China 1,340 Mil. India 1,210 mil. Situated at a cross‐road of 3 large economic centers. -

46399E642.Pdf

PGDS in DOS Myanmar Atlas Map Population and Geographic Data Section As of January 2006 Division of Operational Support Email : [email protected] ((( Yüeh-hsi ((( ((( Zayü ((( ((( BANGLADESHBANGLADESH ((( Xichang ((( Zhongdian ((( Ho-pien-tsun Cox'sCox's BazarBazar ((( ((( ((( ((( Dibrugrh ((( ((( ((( (((Meiyu ((( Dechang THIMPHUTHIMPHU ((( ((( ((( Myanmar_Atlas_A3PC.WOR ((( Ningnan ((( ((( Qiaojia ((( Dayan ((( Yongsheng KutupalongKutupalong ((( Huili ((( ((( Golaghat ((( Jianchuan ((( Huize ((( ((( ((( Cooch Behar ((( North Gauhati Nowgong (((( ((( Goalpara (((( Gauhati MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( MYANMARMYANMAR ((( Dinhata ((( ((( Gauripur ((( Dongch ((( ((( ((( Dengchuan ((( Longjie ((( Lalmanir Hat ((( Yanfeng ((( Rangpur ((( ((( ((( ((( Yuanmou ((( Yangbi((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( INDIAINDIA ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Shillong ((((( Xundia ((( ((( Hai-tzu-hsin ((( Yongping ((( Xiangyun ((( ((( ((( Myitkyina ((( ((( ((( Heijing ((( Gaibanda NayaparaNayapara ((((( ((( (Sha-chiao(( ((( ((( ((( ((( Yipinglang ((( Baoshan TeknafTeknaf ButhidaungButhidaung (((TeknafTeknaf ((( ((( Nanjian ((( !! ((( Tengchong KanyinKanyin((( ChaungChaung !! Kunming ((( ((( ((( Anning ((( ((( ((( Changning MaungdawMaungdaw ((( MaungdawMaungdaw ((( ((( Imphal Mymensingh ((( ((( ((( ((( Jiuyingjiang ((( ((( Longling 000 202020 404040 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH((( 000 202020 404040 BANGLADESHBANGLADESH((( ((( ((( ((( ((( Yunxian ((( ((( ((( ((( -

Mimu875v01 120626 3W Livelihoods South East

Myanmar Information Management Unit 3W South East of Myanmar Livelihoods Border and Country Based Organizations Presence by Township Budalin Thantlang 94°23'EKani Wetlet 96°4'E Kyaukme 97°45'E 99°26'E 101°7'E Ayadaw Madaya Pangsang Hakha Nawnghkio Mongyai Yinmabin Hsipaw Tangyan Gangaw SAGAING Monywa Sagaing Mandalay Myinmu Pale .! Pyinoolwin Mongyang Madupi Salingyi .! Matman CHINA Ngazun Sagaing Tilin 1 Tada-U 1 1 2 Monghsu Mongkhet CHIN Myaing Yesagyo Kyaukse Myingyan 1 Mongkaung Kyethi Mongla Mindat Pauk Natogyi Lawksawk Kengtung Myittha Pakokku 1 1 Hopong Mongping Taungtha 1 2 Mongyawng Saw Wundwin Loilen Laihka Ü Nyaung-U Kunhing Seikphyu Mahlaing Ywangan Kanpetlet 1 21°6'N Paletwa 4 21°6'N MANDALAY 1 1 Monghpyak Kyaukpadaung Taunggyi Nansang Meiktila Thazi Pindaya SHAN (EAST) Chauk .! Salin 4 Mongnai Pyawbwe 2 Tachileik Minbya Sidoktaya Kalaw 2 Natmauk Yenangyaung 4 Taunggyi SHAN (SOUTH) Monghsat Yamethin Pwintbyu Nyaungshwe Magway Pinlaung 4 Mawkmai Myothit 1 Mongpan 3 .! Nay Pyi Hsihseng 1 Minbu Taw-Tatkon 3 Mongton Myebon Langkho Ngape Magway 3 Nay Pyi Taw LAOS Ann MAGWAY Taungdwingyi [(!Nay Pyi Taw- Loikaw Minhla Nay Pyi Pyinmana 3 .! 3 3 Sinbaungwe Taw-Lewe Shadaw Pekon 3 3 Loikaw 2 RAKHINE Thayet Demoso Mindon Aunglan 19°25'N Yedashe 1 KAYAH 19°25'N 4 Thandaunggyi Hpruso 2 Ramree Kamma 2 3 Toungup Paukkhaung Taungoo Bawlakhe Pyay Htantabin 2 Oktwin Hpasawng Paungde 1 Mese Padaung Thegon Nattalin BAGOPhyu (EAST) BAGO (WEST) 3 Zigon Thandwe Kyangin Kyaukkyi Okpho Kyauktaga Hpapun 1 Myanaung Shwegyin 5 Minhla Ingapu 3 Gwa Letpadan -

BAGO REGION, PYAY DISTRICT Paukkhaung Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census BAGO REGION, PYAY DISTRICT Paukkhaung Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Bago Region, Pyay District Paukkhaung Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Bago Region, showing the townships Paukkhaung Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 124,856 2 Population males 60,941 (48.8%) Population females 63,915 (51.2%) Percentage of urban population 11.2% Area (Km2) 1,907.6 3 Population density (per Km2) 65.5 persons Median age 30.2 years Number of wards 5 Number of village tracts 53 Number of private households 32,347 Percentage of female headed households 16.5% Mean household size 3.8 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 24.0% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 69.8% Elderly population (65+ years) 6.2% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 43.2 Child dependency ratio 34.4 Old dependency ratio 8.8 Ageing index 25.6 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 95 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 93.5% Male 96.5% Female 90.9% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 5,435 4.4 Walking 2,218 1.8 Seeing 3,001 2.4 Hearing 1,865 1.5 Remembering 2,147 1.7 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 73,352 69.3 Associate -

Desk Review Cover and Contents.Indd

BASELINE ASSESSMENT OF COMMUNITY BASED TB SERVICES IN 8 ENGAGE-TB PRIORITY COUNTRIES WHO/CDS/GTB/THC/18.34 © World Health Organization 2018 Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo). Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”. Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization. Suggested citation. Baseline assessment of community based TB services in 8 WHO ENGAGE-TB priority countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018 (WHO/CDS/GTB/THC/18.34). Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris. -

BAGO REGION, PYAY DISTRICT Pyay Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census BAGO REGION, PYAY DISTRICT Pyay Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Bago Region, Pyay District Pyay Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Bago Region, showing the townships Pyay Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 251,643 2 Population males 119,670 (47.6%) Population females 131,973 (52.4%) Percentage of urban population 53.6% Area (Km2) 788.4 3 Population density (per Km2) 319.2 persons Median age 31.4 years Number of wards 10 Number of village tracts 55 Number of private households 58,557 Percentage of female headed households 24.2% Mean household size 4.0 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 21.1% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 71.9% Elderly population (65+ years) 7.0% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 39.2 Child dependency ratio 29.4 Old dependency ratio 9.8 Ageing index 33.2 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 91 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 96.9% Male 98.5% Female 95.5% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 9,557 3.8 Walking 3,883 1.5 Seeing 5,416 2.2 Hearing 3,011 1.2 Remembering 2,901 1.2 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per cent Citizenship Scrutiny 162,993 74.5 Associate Scrutiny -

Laboratory Aspects in Vpds Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation

Laboratory Aspect of VPD Surveillance and Outbreak Investigation Dr Ommar Swe Tin Consultant Microbiologist In-charge National Measles & Rubella Lab, Arbovirus section, National Influenza Centre NHL Fever with Rash Surveillance Measles and Rubella Achieving elimination of measles and control of rubella/CRS by 2020 – Regional Strategic Plan Key Strategies: 1. Immunization 2. Surveillance 3. Laboratory network 4. Support & Linkages Network of Regional surveillance officers (RSO) and Laboratories NSC Office 16 RSOs Office Subnational Measles & Rubella Lab, Subnational JE lab National Measles/Rubella Lab (NHL, Yangon) • Surveillance began in 2003 • From 2005 onwards, case-based diagnosis was done • Measles virus isolation was done since 2006 • PCR since 2016 Sub-National Measles/Rubella Lab (PHL, Mandalay) • Training 29.8.16 to 2.9.16 • Testing since Nov 2016 • Accredited in Oct 2017 Measles Serology Data Measles Measles IgM Measles IgM Measles IgM Test Done Positive Negative Equivocal 2011 1766 1245 452 69 2012 1420 1182 193 45 2013 328 110 212 6 2014 282 24 254 4 2015 244 6 235 3 2016 531 181 334 16 2017 1589 1023 503 62 Rubella Serology Data Rubella Test Rubella IgM Rubella IgM Rubella IgM Done Positive Negative Equivocal 2011 425 96 308 21 2012 195 20 166 9 2013 211 23 185 3 2014 257 29 224 4 2015 243 34 196 13 2016 535 12 511 12 2017 965 8 948 9 Measles Genotypes circulating in Myanmar 1. Isolation in VERO h SLAM cell line 2. Positive culture shows syncytia formation 3. Isolated MeV or sample by PCR 4. Positive PCR product is sent to RRL for sequencing 5. -

Patterns of Anti-Muslim Violence in Burma: a Call for Accountability and Prevention

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Publications and Research City College of New York 2013 Patterns of Anti-Muslim Violence in Burma: A Call for Accountability and Prevention Andrea Gittleman Physicians for Human Rights Marissa Brodney Physicians for Human Rights Holly G. Atkinson CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_pubs/408 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Physicians for Patterns of Anti-Muslim Human Rights Violence in Burma: A Call for Accountability August 2013 and Prevention A mother looks out from her tent alongside physiciansforhumanrights.org her children at a camp for internally displaced persons on the outskirts of Sittwe, Burma. Photo: Paula Bronstein/Getty Images About Physicians for Human Rights For more than 25 years, PHR’s use of science and medicine has been on the cutting edge of human rights work. 1986 2003 Led investigations of torture in Warned U.S. policymakers on health Chile, gaining freedom for heroic and human rights conditions prior doctors there to and during the invasion of Iraq 1988 2004 First to document the Iraqi use Documented genocide and sexual of chemical weapons on Kurds, violence in Darfur in support of providing evidence for prosecution international prosecutions of war criminals 2010 1996 Investigated the epidemic of Exhumed mass graves -

Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar

Myanmar Development Research (MDR) (Present) Enlightened Myanmar Research (EMR) Wing (3), Room (A-305) Thitsar Garden Housing. 3 Street , 8 Quarter. South Okkalarpa Township. Yangon, Myanmar +951 562439 Acknowledgement of Myanmar Development Research This edition of the “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)” is the first published collection of facts and information of political parties which legally registered at the Union Election Commission since the pre-election period of Myanmar’s milestone 2010 election and the post-election period of the 2012 by-elections. This publication is also an important milestone for Myanmar Development Research (MDR) as it is the organization’s first project that was conducted directly in response to the needs of civil society and different stakeholders who have been putting efforts in the process of the political transition of Myanmar towards a peaceful and developed democratic society. We would like to thank our supporters who made this project possible and those who worked hard from the beginning to the end of publication and launching ceremony. In particular: (1) Heinrich B�ll Stiftung (Southeast Asia) for their support of the project and for providing funding to publish “Fact Book of Political Parties in Myanmar (2010-2012)”. (2) Party leaders, the elected MPs, record keepers of the 56 parties in this book who lent their valuable time to contribute to the project, given the limited time frame and other challenges such as technical and communication problems. (3) The Chairperson of the Union Election Commission and all the members of the Commission for their advice and contributions. -

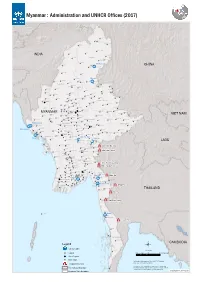

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017)

Myanmar : Administration and UNHCR Offices (2017) Nawngmun Puta-O Machanbaw Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Sumprabum Lahe Tanai INDIA Tsawlaw Hkamti Kachin Chipwi Injangyang Hpakan Myitkyina Lay Shi Myitkyina CHINA Mogaung Waingmaw Homalin Mohnyin Banmauk Bhamo Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Momauk Pinlebu Katha Sagaing Mansi Muse Wuntho Konkyan Kawlin Tigyaing Namhkan Tonzang Mawlaik Laukkaing Mabein Kutkai Hopang Tedim Kyunhla Hseni Manton Kunlong Kale Kalewa Kanbalu Mongmit Namtu Taze Mogoke Namhsan Lashio Mongmao Falam Mingin Thabeikkyin Ye-U Khin-U Shan (North) ThantlangHakha Tabayin Hsipaw Namphan ShweboSingu Kyaukme Tangyan Kani Budalin Mongyai Wetlet Nawnghkio Ayadaw Gangaw Madaya Pangsang Chin Yinmabin Monywa Pyinoolwin Salingyi Matman Pale MyinmuNgazunSagaing Kyethi Monghsu Chaung-U Mongyang MYANMAR Myaung Tada-U Mongkhet Tilin Yesagyo Matupi Myaing Sintgaing Kyaukse Mongkaung VIET NAM Mongla Pauk MyingyanNatogyi Myittha Mindat Pakokku Mongping Paletwa Taungtha Shan (South) Laihka Kunhing Kengtung Kanpetlet Nyaung-U Saw Ywangan Lawksawk Mongyawng MahlaingWundwin Buthidaung Mandalay Seikphyu Pindaya Loilen Shan (East) Buthidaung Kyauktaw Chauk Kyaukpadaung MeiktilaThazi Taunggyi Hopong Nansang Monghpyak Maungdaw Kalaw Nyaungshwe Mrauk-U Salin Pyawbwe Maungdaw Mongnai Monghsat Sidoktaya Yamethin Tachileik Minbya Pwintbyu Magway Langkho Mongpan Mongton Natmauk Mawkmai Sittwe Magway Myothit Tatkon Pinlaung Hsihseng Ngape Minbu Taungdwingyi Rakhine Minhla Nay Pyi Taw Sittwe Ann Loikaw Sinbaungwe Pyinma!^na Nay Pyi Taw City Loikaw LAOS Lewe -

Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine

Urban Development Plan Development Urban The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Ministry of Construction for Regional Cities The Republic of the Union of Myanmar Urban Development Plan for Regional Cities - Mawlamyine and Pathein Mandalay, - Mandalay, Pathein and Mawlamyine - - - REPORT FINAL Data Collection Survey on Urban Development Planning for Regional Cities FINAL REPORT <SUMMARY> August 2016 SUMMARY JICA Study Team: Nippon Koei Co., Ltd. Nine Steps Corporation International Development Center of Japan Inc. 2016 August JICA 1R JR 16-048 Location業務対象地域 Map Pannandin 凡例Legend / Legend � Nawngmun 州都The Capital / Regional City Capitalof Region/State Puta-O Pansaung Machanbaw � その他都市Other City and / O therTown Town Khaunglanhpu Nanyun Don Hee 道路Road / Road � Shin Bway Yang � 海岸線Coast Line / Coast Line Sumprabum Tanai Lahe タウンシップ境Township Bou nd/ Townshipary Boundary Tsawlaw Hkamti ディストリクト境District Boundary / District Boundary INDIA Htan Par Kway � Kachinhin Chipwi Injangyang 管区境Region/S / Statetate/Regi Boundaryon Boundary Hpakan Pang War Kamaing � 国境International / International Boundary Boundary Lay Shi � Myitkyina Sadung Kan Paik Ti � � Mogaung WaingmawミッチMyitkyina� ーナ Mo Paing Lut � Hopin � Homalin Mohnyin Sinbo � Shwe Pyi Aye � Dawthponeyan � CHINA Myothit � Myo Hla Banmauk � BANGLADESH Paungbyin Bhamo Tamu Indaw Shwegu Katha Momauk Lwegel � Pinlebu Monekoe Maw Hteik Mansi � � Muse�Pang Hseng (Kyu Koke) Cikha Wuntho �Manhlyoe (Manhero) � Namhkan Konkyan Kawlin Khampat Tigyaing � Laukkaing Mawlaik Tonzang Tarmoenye Takaung � Mabein -

Page 1 95°15'E 95°30'E Seikphyu Kanpetlet Saw Nyaung-U Laihka

Probable Flood Inundated Area in Okpho, Minhla, Monyo, Ingapu and Hinthada Townships (as of 9 August 2020, 06:15 AM) Kwayt Ma Ku Lar Tet Twin (Ku Lar Tet Htun) San Gyi Dambi Myauk Lut Kone Gon Taw In Taing Pu Nyaung Pin Kone Myo Ka Lay 95°15'E Seik Gyi Za Yat Hla 95°30'E Son Le Ma Me Lay (Ma Me) Myanmar Zee Kone Bon Shey Kone (West) Thit Ta Yar Le Taw Chaung Zauk Shan Su Aung Thu Kha Htan Pin Kone Myo Soe Lel U Su Bone Su Ma Gyi Su Tha Pyay Hla Seikp hyu Lawksawk Laihka Thea Hpyu Pauk Taing Ywar Shey Saw Nyaung-U M ahlaing Y wangan Ma Me Gyi Tha Pyay San Kwayt Gyi Bu Da Let KoneKanp e tlet Pakokku Aung Chan Thar Loilen Thea Hpyu Thu Htay Kone Ywar Thit Pind aya Gway Kyar Su Oe Bo Kone Khun Hnit Tar Tha Khut Tan (West) Ta Man Gyi Kyaukp adaung M e iktila Taunggyi Leik Lut Tar Su Min Su Bu DaThazi Let Kone !. Nansang Thit Seint Kone Tha But Gyi Taw Chauk Hop ong Salin Nyaung Pin BoTaunggyi Ywar Thit Pauk Taing Kyun Gyi Shwedaung Aung Chan Thar Kya Khat War Yon (Ah Shey Su) Kalaw Gway Pin Kone Pwe Thar Kwayt Ka Lay Nyaung Ngoke To Kyoet Kone Tar Kyoe M inb ya Pyawbwe M ongnai Kyauk Sa Yit Kone Ka Nyan Swei TawSidoktaya Kone Ma Gyi Kone Natmauk Let Pan Pin Kan Ka Lay Chaung Thone Gwa Thin Aing Daw Kyaw (West) Y e nangyaungNyaung Zin Pauk Taw Kant Lant Kone Yin Mu Kone Nyaung Waing Kywe Thay Y ame thin Zigon Myay Char GyeikPwintbyu Taw Lay Nyaungshwe Lone La Daw Kyaw (East) Put Su Shar Hpyu Kone Kywe Te Thaung Pyin Kone Koke Ko Myaung Kan Lel Te Gyi Kone Magway M awkm ai M ongp an Kywe Thay (North) Ku Lar !.