Rapid Urban Diagnostic Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

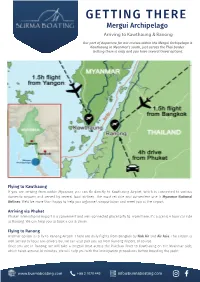

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong

GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Arriving to Kawthaung & Ranong Our port of departure for our cruises within the Mergui Archipelago is Kawthaung in Myanmar’s south, just across the Thai border. Getting there is easy and you have several travel options. Flying to Kawthaung If you are arriving from within Myanmar, you can fly directly to Kawthaung Airport, which is connected to various domestic airports and served by several local airlines. The most reliable and convenient one is Myanmar National Airlines. We’d be more than happy to help you organise transportation and meet you at the airport. Arriving via Phuket Phuket International Airport is a convenient and well-connected place to fly to. From there, it’s a scenic 4 hour car ride to Ranong. We can help you to book a car & driver. Flying to Ranong Another option is to fly to Ranong Airport. There are daily flights from Bangkok by Nok Air and Air Asia. The airport is well served by local taxi drivers but we can also pick you up from Ranong Airport, of course. Once you are in Ranong, we will take a longtail boat across the Pakchan River to Kawthaung on the Myanmar side, which takes around 30 minutes. We will help you with the immigration procedures before boarding the yacht. www.burmaboating.com +66 2 1070 445 [email protected] GETTING THERE Mergui Archipelago Crossing the Thai-Myanmar border In the case you arrive through the Thailand side and doesn’t want our assistance, here is a quick step by step instruction to cross the border between the 2 countries. -

TRENDS in MANDALAY Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY Photo credits Paul van Hoof Mithulina Chatterjee Myanmar Survey Research The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN MANDALAY UNDP MYANMAR Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 11 2. Methodology 14 2.1 Objectives 15 2.2 Research tools 15 3. Introduction to Mandalay region and participating townships 18 3.1 Socio-economic context 20 3.2 Demographics 22 3.3 Historical context 23 3.4 Governance institutions 26 3.5 Introduction to the three townships participating in the mapping 33 4. Governance at the frontline: Participation in planning, responsiveness for local service provision and accountability 38 4.1 Recent developments in Mandalay region from a citizen’s perspective 39 4.1.1 Citizens views on improvements in their village tract or ward 39 4.1.2 Citizens views on challenges in their village tract or ward 40 4.1.3 Perceptions on safety and security in Mandalay Region 43 4.2 Development planning and citizen participation 46 4.2.1 Planning, implementation and monitoring of development fund projects 48 4.2.2 Participation of citizens in decision-making regarding the utilisation of the development funds 52 4.3 Access to services 58 4.3.1 Basic healthcare service 62 4.3.2 Primary education 74 4.3.3 Drinking water 83 4.4 Information, transparency and accountability 94 4.4.1 Aspects of institutional and social accountability 95 4.4.2 Transparency and access to information 102 4.4.3 Civil society’s role in enhancing transparency and accountability 106 5. -

MANDALAY REGION, PYIN OO LWIN DISTRICT Pyin Oo Lwin Township Report

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census MANDALAY REGION, PYIN OO LWIN DISTRICT Pyin Oo Lwin Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population October 2017 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Mandalay Region, Pyin Oo Lwin District Pyin Oo Lwin Township Report Department of Population Ministry of Labour, Immigration and Population Office No.48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431062 www.dop.gov.mm October 2017 Figure 1 : Map of Mandalay Region, showing the townships Pyin Oo Lwin Township Figures at a Glance 1 Total Population 255,508 2 Population males 128,027 (50.1%) Population females 127,481 (49.9%) Percentage of urban population 62.1% Area (Km2) 1,978.1 3 Population density (per Km2) 129.2 persons Median age 26.8 years Number of wards 21 Number of village tracts 37 Number of private households 53,382 Percentage of female headed households 22.6% Mean household size 4.3 persons 4 Percentage of population by age group Children (0 – 14 years) 24.7% Economically productive (15 – 64 years) 70.7% Elderly population (65+ years) 4.6% Dependency ratios Total dependency ratio 41.3 Child dependency ratio 34.9 Old dependency ratio 6.4 Ageing index 18.5 Sex ratio (males per 100 females) 100 Literacy rate (persons aged 15 and over) 95.4% Male 97.5% Female 93.4% People with disability Number Per cent Any form of disability 5,334 2.1 Walking 2,190 0.9 Seeing 2,633 1.0 Hearing 1,334 0.5 Remembering 1,454 0.6 Type of Identity Card (persons aged 10 and over) Number Per -

Improvement of Meteorological

IMPROVEMENT OF METEOROLOGICAL OBSERVATION SYSTEM IN MYANMAR By Hla Tun Office No (5), Ministry of Transport and Communications, Department of Meteorology and Hydrology, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar Tel. +95 67 411 250, +95 9 860 1162, Mobile Phone: +95 250 954 642, Fax : (+95) 67 411 526 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Department of Meteorology and Hydrology (DMH) is under the administration of the Ministry of Transport and Communications. Main works performed by DMH are routine observation and analysis of meteorological phenomena, and providing of timely and accurate weather and climate information through acquisition of weather monitoring and dissemination systems for the general public. DMH also provides meteorological and hydrological information for shipping and aviation as well as agricultural and environment activities. Before Cyclonic Storm "Nargis", (103) surface weather observation stations in Myanmar used manual observing system. As at then, we are improved on installation of Automated Weather Observing Systems at 14 stations including at former Headquarter of National Meteorological Center (NMCs) namely Yangon (Kaba-aye) and new Headquarter of National Meteorological Center (NMCs) namely Nay Pyi Taw. Early months of this year (2016), regarding the Grant Aid Project of Japan, we installed additional Surface Automated Weather Observing Systems (AWS) at existing 30 Meteorological observation stations such as Nay Pyi Taw (Early Warning Center), Yangon (Kaba-aye), Mandalay, Putao, Myitkyina, Bhamo, Lashio, Taunggyi, Kengtung, Namsam, Hakha, Hkamti, Kalay, Monywa, Meikhtila, Magway, Sittwe, Kyauk-phyu, Thandwe, Gwa, Taungu, Bago, Hmawbi, Pathein, Laputta, Loikaw, Hpa-an, Mawlamyine, Dawei and Kawthong. Furthermore, one of the three (3) new Doppler Weather Radars, it is already installed in 2015 and remaining two radars we expected to be completed middle of this year and the project will be complete by next year of 2017. -

Mandalay Region Census Report Volume 3 – L

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Mandalay Region Census Report Volume 3 – l Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census Mandalay Region Report Census Report Volume 3 – I For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 2: Map of Mandalay Region, Districts and Townships ii Census Report Volume 3–I (Mandalay) Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is now my hope that the main results both Union and each of the State and Region reports will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national and sub-national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and officers at the State/Region, District and Township levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

Military Brotherhood Between Thailand and Myanmar: from Ruling to Governing the Borderlands

1 Military Brotherhood between Thailand and Myanmar: From Ruling to Governing the Borderlands Naruemon Thabchumphon, Carl Middleton, Zaw Aung, Surada Chundasutathanakul, and Fransiskus Adrian Tarmedi1, 2 Paper presented at the 4th Conference of the Asian Borderlands Research Network conference “Activated Borders: Re-openings, Ruptures and Relationships”, 8-10 December 2014 Southeast Asia Research Centre, City University of Hong Kong 1. Introduction Signaling a new phase of cooperation between Thailand and Myanmar, on 9 October 2014, Thailand’s new Prime Minister, General Prayuth Chan-o-cha took a two-day trip to Myanmar where he met with high-ranked officials in the capital Nay Pi Taw, including President Thein Sein. That this was Prime Minister Prayuth’s first overseas visit since becoming Prime Minister underscored the significance of Thailand’s relationship with Myanmar. During their meeting, Prime Minister Prayuth and President Thein Sein agreed to better regulate border areas and deepen their cooperation on border related issues, including on illicit drugs, formal and illegal migrant labor, including how to more efficiently regulate labor and make Myanmar migrant registration processes more efficient in Thailand, human trafficking, and plans to develop economic zones along border areas – for example, in Mae 3 Sot district of Tak province - to boost trade, investment and create jobs in the areas . With a stated goal of facilitating border trade, 3 pairs of adjacent provinces were named as “sister provinces” under Memorandums of Understanding between Myanmar and Thailand signed by the respective Provincial governors during the trip.4 Sharing more than 2000 kilometer of border, both leaders reportedly understood these issues as “partnership matters for security and development” (Bangkok Post, 2014). -

Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State

A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State ASIA PAPER May 2018 EUROPEAN UNION A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State © Institute for Security and Development Policy V. Finnbodavägen 2, Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden www.isdp.eu “A Return to War: Militarized Conflicts in Northern Shan State” is an Asia Paper published by the published by the Institute for Security and Development Policy. The Asia Paper Series is the Occasional Paper series of the Institute’s Asia Program, and addresses topical and timely subjects. The Institute is based in Stockholm, Sweden, and cooperates closely with research centers worldwide. The Institute serves a large and diverse community of analysts, scholars, policy-watchers, business leaders, and journalists. It is at the forefront of research on issues of conflict, security, and development. Through its applied research, publications, research cooperation, public lectures, and seminars, it functions as a focal point for academic, policy, and public discussion. This publication has been produced with funding by the European Union. The content of this publication does not reflect the official opinion of the European Union. Responsibility for the information and views expressed in the paper lies entirely with the authors. No third-party textual or artistic material is included in the publication without the copyright holder’s prior consent to further dissemination by other third parties. Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. © European Union and ISDP, 2018 Printed in Lithuania ISBN: 978-91-88551-11-5 Cover photo: Patrick Brown patrickbrownphoto.com Distributed in Europe by: Institute for Security and Development Policy Västra Finnbodavägen 2, 131 30 Stockholm-Nacka, Sweden Tel. -

A Case Study from Myanmar How to Inform, Empower, and Impact Communities

INFORMATION ECOSYSTEMS in transition: A case stUDY from myanmar HOW to inform, emPOWer, anD imPact commUnities Mon State, Myanmar Pilot Study PART ONE: RESEARCH FINDINGS ABOUT THE AUTHORS ABOUT THE RESEARCH TEAM EXecUtiVE SUmmary Andrew Wasuwongse is a graduate of the Johns Hopkins Established in 1995, Myanmar Survey Research (MSR) University’s School of Advanced International Studies in is a market and social research company based in Washington, DC. He holds a master’s degree in International Yangon, Myanmar. MSR has produced over 650 Relations and International Economics, with a concentration research reports in the fields of social, market, and in Southeast Asia Studies. While a research assistant for environmental research over the past 16 years for UN the SAIS Burma Study Group, he supported visits by three agencies, INGOs, and business organizations. Burmese government delegations to Washington, DC, including officials from Myanmar’s Union Parliament, ABOUT INTERNEWS in MYANMAR Ministry of Health, and Ministry of Industry. He has worked as a consultant for World Vision Myanmar, where he led an Internews is an international nonprofit organization whose assessment of education programs in six regions across mission is to empower local media worldwide to give people Myanmar, and has served as an English teacher in Kachin the news and information they need, the ability to connect State, Myanmar, and in Thailand on the Thai-Myanmar border. and the means to make their voices heard. Internews He speaks Thai and Burmese. provides communities with the resources to produce local news and information with integrity and independence. Alison Campbell is currently Internews’ Senior Director With global expertise and reach, Internews trains both media for Global Initiatives based in Washington, DC, overseeing professionals and citizen journalists, introduces innovative Internews’ environmental, health and humanitarian media solutions, increases coverage of vital issues and helps programs. -

Gulf of Mottama Management Plan

GULF OF MOTTAMA MANAGEMENT PLAN PROJECT IMPLEMTATION AND COORDINATION UNIT – PCIU COVER DESIGN: 29, MYO SHAUNG RD, TAUNG SHAN SU WARD, MAWLAMYINE, NYANSEIK RARMARN MON STATE, MYANMAR KNOWLEDGE MANAGEMENT AND COMMUNICATION OFFICER GULF OF MOTTAMA PROJECT (GOMP) Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 GULF OF MOTTAMA MANAGEMENT PLAN Published: 16 May 2019 This management plan is endorsed by Mon State and Bago Regional Governments, to be adopted as a guidance document for natural resource management and sustainable development for resilient communities in the Gulf of Mottama. 1 Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 This page is intentionally left blank 2 Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 Gulf of Mottama Project (GoMP) GoMP is a project of Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) and is implemented by HELVETAS Myanmar, Network Activities Group (NAG), International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and Biodiversity and Nature Conservation Association(BANCA). 3 Gulf of Mottama Management Plan, May 2019 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The drafting of this Gulf of Mottama Management Plan started early 2016 with an integrated meeting on May 31 to draft the first concept. After this initial workshop, a series of consultations were organized attended by different people from several sectors. Many individuals and groups actively participated in the development of this management plan. We would like to acknowledge the support of the Ministries and Departments who have been actively involved at the Union level which more specifically were Ministry of Natural Resource and Environmental Conservation, Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock and Irrigation, Forest Department, Department of Agriculture, Department of Fisheries, Department of Rural Development and Environmental Conservation Department. -

Evaluation of the Myanmar Coc Dossier and MTLAS

Evaluation of the Myanmar CoC Dossier and MTLAS By Christian Sloth and Kyaw Htun 19 February 2020 Report developed on behalf of European Timber Trade Federation Blank page 2 Contents Contents .............................................................................................................. 3 Acronyms ............................................................................................................. 4 Acknowledgements ................................................................................................ 5 1 Introduction .................................................................................................... 6 1.1 About this report........................................................................................... 6 2 Background .................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Forest governance and legality – a perspective on current situation .................... 9 2.2 Forest resources ......................................................................................... 10 2.3 Forest management and harvesting .............................................................. 14 2.3 Timber trade .............................................................................................. 20 2.4 Applicable forest laws and regulations ........................................................... 24 2.5 Timber sources in Myanmar ......................................................................... 28 2.6 Timber tracking ......................................................................................... -

Myanmar Public Disclosure Authorized

SFG1932 REV Republic of the Union of Myanmar Public Disclosure Authorized Myanmar Flood and Landslides Emergency Recovery Project Environmental and Social Management Framework (ESMF) Public Disclosure Authorized May 23rd, 2016 [Revised Draft] Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Table of Contents Abbreviations _____________________________________________________________________ 3 I. Background ______________________________________________________________ 4 II. Project Development Objective ______________________________________________ 7 III. Project Description ________________________________________________________ 7 IV. Project Locations and Some Salient Social and Environmental Characteristics ______ 9 V. Possible Social and Environmental Impacts/Risks ______________________________ 11 VI. Legal Framework ______________________________________________________ 13 VII. National Legal Framework ______________________________________________ 13 VIII. Categorization and World Bank Safeguard Policies Triggered __________________ 17 IX. Project approach to Addressing Environmental and Social Safeguard issues _______ 21 X. Institutional Arrangements ________________________________________________ 25 XI. Project Monitoring and Grievance Mechanism (GRM) _________________________ 30 XII. Capacity Development Plan ______________________________________________ 32 XIII. Estimated Cost ________________________________________________________ 33 XIV. Consultation and Disclosure _____________________________________________