Ashes to Kailash, 1999

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Example from the Himalaya

Three-dimensional strain accumulation and partitioning in an arcuate orogenic wedge: An example from the Himalaya Suoya Fan†, and Michael A. Murphy Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Houston, Houston, Texas 77204, USA ABSTRACT high-elevation, low-relief surface in the 1939; Gansser, 1964; Le Fort, 1975; Burg and Mugu-Dolpa region of west Nepal. We pro- Chen, 1984; Pêcher, 1989). This suggests along- In this study, we use published geologic pose that these results can be explained by strike continuity in the structural architecture, maps and cross-sections to construct a three- oblique convergence along a megathrust with tectonostratigraphy, and possible evolution. dimensional geologic model of major shear an along-strike and down-dip heterogeneous However, several studies have since observed zones that make up the Himalayan orogenic coupling pattern infuenced by frontal and and better understand that signifcant differences wedge. The model incorporates microseis- oblique ramps along the megathrust. exist (e.g., Paudel and Arita, 2002; Thiede et al., micity, megathrust coupling, and various de- 2006; Yin, 2006; Murphy, 2007; Hintersberger rivatives of the topography to address several INTRODUCTION et al., 2010; Webb et al., 2011; Carosi et al., questions regarding observed crustal strain 2013). In the western and central Himalaya, patterns and how they are expressed in the Studies on the growth of orogenic wedges geologic features indicative of different along- landscape. These questions include: (1) How usually focus on processes normal to the strike strike structural styles and histories comprise does vertical thickening vary along strike of of the orogen by assuming plane strain defor- thrust duplexes, gneiss domes, and intermontane the orogen? (2) What is the role of oblique mation. -

Syncollisional Extension Along the India–Asia Suture Zone, South-Central Tibet: Implications for Crustal Deformation of Tibet

ARTICLE IN PRESS EPSL-10123; No of Pages 11 Earth and Planetary Science Letters xxx (2010) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Earth and Planetary Science Letters journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Syncollisional extension along the India–Asia suture zone, south-central Tibet: Implications for crustal deformation of Tibet M.A. Murphy a,⁎, V. Sanchez a, M.H. Taylor b a University of Houston, 312 Science and Research Bldg. 1, Houston, TX 772004-5007, United States b Department of Geology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS 66045, United States article info abstract Article history: Crustal deformation models of the Tibetan plateau are assessed by investigating the nature of Neogene Received 15 October 2009 deformation along the India–Asia suture zone through geologic mapping in south-central Tibet (84°30′E). Received in revised form 18 November 2009 Our mapping shows that the suture zone is dominated by a system of 3 to 4 ENE-striking, south-dipping Accepted 20 November 2009 thrust faults, rather than strike-slip faults as predicted by models calling upon eastward extrusion of the Available online xxxx Tibetan plateau. Faults along the suture zone are not active, as they are cut by a system of NNW-striking Editor: T.M. Harrison oblique slip normal faults, referred to herein as the Lopukangri fault system. Fault-slip data from the Lopukangri fault system shows that the mean slip direction of its hanging wall is N36W. We estimate the net Keywords: slip on the Lopukangri fault by restoring components of the thrust system. We estimate that the fault has Himalaya accommodated ∼7 km of right-slip and ∼8 km of normal dip-slip, yielding a net slip of ∼10.5 km, and 6 km Tibet of horizontal east–west extension. -

This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached Copy Is Furnished to the Author for Internal Non-Commerci

This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier’s archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright Author's personal copy Tectonophysics 501 (2011) 28–40 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Tectonophysics journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto Cenozoic anatexis and exhumation of Tethyan Sequence rocks in the Xiao Gurla Range, Southwest Tibet Alex Pullen a,⁎, Paul Kapp a, Peter G. DeCelles a, George E. Gehrels a, Lin Ding b a Department of Geosciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA b Institute of Tibetan Plateau Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100029, China article info abstract Article history: In order to advance our understanding of the suturing process between continental landmasses, a geologic Received 5 March 2010 and geochronologic investigation was undertaken just south of the India–Asia suture in southwestern Tibet. Received in revised form 30 December 2010 The focus of this study, the Xiao Gurla Range, is located near the southeastern terminus of the active, right- Accepted 5 January 2011 lateral strike-slip Karakoram fault in southwestern Tibet. -

The Pundits: British Exploration of Tibet and Central Asia

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Asian History History 1990 The Pundits: British Exploration of Tibet and Central Asia Derek Waller Vanderbilt University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Waller, Derek, "The Pundits: British Exploration of Tibet and Central Asia" (1990). Asian History. 1. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_asian_history/1 THE PUNDITS For Penny THE PUNDITS British Exploration of Tibet and Central Asia DEREK WALLER THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright© 1990 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2004 The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Maps in this book were created by Lawrence Brence. Relief rendering from The New International Atlas © 1988 by Rand McNally & Co., R.L. -

Quaternary Glaciation of Gurla Mandhata (Naimon’Anyi) 57 3 58 4 A,* B C a 59 5 Lewis A

Our reference: JQSR 2724 P-authorquery-v7 AUTHOR QUERY FORM Journal: JQSR Please e-mail or fax your responses and any corrections to: E-mail: [email protected] Article Number: 2724 Fax: +31 2048 52789 Dear Author, Any queries or remarks that have arisen during the processing of your manuscript are listed below and highlighted by flags in the proof. Please check your proof carefully and mark all corrections at the appropriate place in the proof (e.g., by using on-screen annotation in the PDF file) or compile them in a separate list. For correction or revision of any artwork, please consult http://www.elsevier.com/artworkinstructions. Articles in Special Issues: Please ensure that the words ‘this issue’ are added (in the list and text) to any references to other articles in this Special Issue. Uncited references: References that occur in the reference list but not in the text e please position each reference in the text or delete it from the list. Missing references: References listed below were noted in the text but are missing from the reference list e please make the list complete or remove the references from the text. Location in Query / remark article Please insert your reply or correction at the corresponding line in the proof Q1 Please update the reference Dortch et al., in press Electronic file usage Sometimes we are unable to process the electronic file of your article and/or artwork. If this is the case, we have proceeded by: , Scanning (parts of) your article , Rekeying (parts of) your article , Scanning the artwork Thank you for your assistance. -

Feasibility Assessment Report

Chapter 2 – Description of Target Landscape Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative Feasibility Assessment Report 1 Kang Rinpoche གངས་རིན་པོ་ཆེ – Gangrénboqí Feng 冈仁波齐峰 – Kaila´sa Parvata s}nfz kj{t Kailash Sacred Landscape Conservation Initiative Feasibility Assessment Report Editors Robert Zomer Krishna Prasad Oli International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Kathmandu, Nepal, July 2011 Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal Copyright © 2011 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) All rights reserved. Published 2011 ISBN 978 92 9115 209 4 (printed) 978 92 9115 211 7 (electronic) LCCN 2011-312010 Photos: p 6, Sally Walkerman; p 38, Govinda Basnet; all others, Robert Zomer Printed and bound in Nepal by Sewa Printing Press, Kathmandu, Nepal Production team Isabella Bassignana-Khadka (Consultant editor) Susan Sellars-Shrestha (Consultant editor) Andrea Perlis (Senior editor) A Beatrice Murray (Senior editor) Dharma R Maharjan (Layout and design) Asha Kaji Thaku (Editorial assistant) Note This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. ICIMOD would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from ICIMOD. The views and interpretations in this publication are those of the author(s). They are not attributable to ICIMOD and do not imply the expression of any opinion concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or the endorsement of any product. -

Destination Himalaya Sacred Mountains & Lakes of Tibet

Destination Himalaya Tours For The Adventurous Traveler Sacred Mountains & Lakes of Tibet In the Footsteps of the Early Explorers Sunset on the North Face of Mt. Everest © Jeff Davis Guge Kingdom Pangong & Manasarovar Lakes Kailash, Shishapangma & Everest May 5th – 20, 2014 (Sagadawa Festival) September 13th – 28th, 2014 October 4th – 19th, 2014 16 Days, Moderate High Altitude Touring 807 Grant Ave. Suite A • Novato, CA 94945 • Ph: 1.415.895.5283 or 1.800.694.6342 • Fax: 1.415-895-5284 www.DestinationHimalaya.net • [email protected] "The center of high snow mountains; The source of great rivers; a lofty country, a pure land." - Unknown Tibetan poet Roof of the Potala Palace n the Roof of the World. Locked away for centuries, Tibet has always held a unique place in the human imagination, conjuring an unearthly realm beyond our reach. What causes our enduring fascination with Tibet? Surely its inaccessibility, mysterious gimps, lunar Olandscape and tenacious people transfix us. In this isolated land cut off from the world for all but the last century, beauty and strangeness appear in equal measure. Frozen peaks and windy flatlands constitute the landscape of this high desert plateau. Beneath an often crystal-blue sky, the Tibetan people exist in a medieval world. Since the occupation by the Chinese, their endurance has been tested both physically and spiritually. Yet despite the hardships of their daily lives, Tibetans remain tolerant and good-humored. Your encounters with these hardy people will leave you with a profound respect for the culture that binds man and women to the cosmos with such generosity of spirit. -

Thermochronologic Constraints on the Late Cenozoic Exhumation History of the Gurla Mandhata Metamorphic Core Complex, Southwestern Tibet

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. Thermochronologic constraints on the late Cenozoic exhumation history of the Gurla Mandhata metamorphic core complex, Southwestern Tibet by A. T. McCallister et al. 2013 This is the published version of the article, made available with the permission of the publisher. The original published version can be found at the link below. A. T. McCallister et al. (2013). Thermochronologic constraints on the late Cenozoic exhumation history of the Gurla Mandhata metamorphic core complex, Southwestern Tibet. Tectonics Published version: http://www.dx.doi.org/10.1002/2013TC003302 Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml KU ScholarWorks is a service provided by the KU Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication & Copyright. PUBLICATIONS Tectonics RESEARCH ARTICLE Thermochronologic constraints on the late Cenozoic 10.1002/2013TC003302 exhumation history of the Gurla Mandhata Key Points: metamorphic core complex, • Fast Exhumation (4-5 mm/yr) since 12 Ma Southwestern Tibet • Similar timing, rate and fault slip as the Karakoram Fault A. T. McCallister1, M. H. Taylor1, M. A. Murphy2, R. H. Styron1, and D. F. Stockli1,3 • ~8 Ma Zr (U-Th)/He Thermochronometic ages across the 1Department of Geology, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas, USA, 2Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, range University of Houston, Houston, Texas, USA, 3Now at Jackson School of Geosciences, University of Texas-Austin, Austin, Texas, USA Correspondence to: M. H. Taylor, Abstract How the Tibetan plateau is geodynamically linked to the Himalayas is a topic receiving [email protected] considerable attention. -

The Late Cenozoic Tectonic Evolution of Gurla Mandhata, Southwest Tibet

The Late Cenozoic tectonic evolution of Gurla Mandhata, Southwest Tibet By Andrew T. McCallister B.S., University of Arizona, 2010 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Geology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. ________________________________ Chairperson: Michael H. Taylor ________________________________ Andreas Mӧller ________________________________ Leigh A. Stearns ________________________________ Daniel F. Stockli Date Defended: October 10/10/2012 The Thesis Committee for Andrew T. McCallister certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Late Cenozoic tectonic evolution of Gurla Mandhata, Southwest Tibet ________________________________ Chairperson: Michael H. Taylor Date approved: 12/3/1012 ii Abstract How strain within the Tibetan plateau is geodynamically linked to that within the Himalayan thrust belt is a topic receiving considerable attention. The right-lateral Karakoram fault plays key roles in models describing the structural relationship between southern Tibet and the Himalaya. Considerable debate exists at the southeastern end of the Karakoram fault, where the role of the Karakoram fault is interpreted in two very different ways. One interpretation states that slip along the Karakoram fault extends eastward along the Indus-Yalu suture zone, thereby bypassing the Himalayan thrust belt to its north. The other, interprets that a significant component of the slip is fed southward into the Himalayan thrust belt along the Gurla Mandhata detachment. To evaluate this debate, the late Miocene fault slip rate history of the Gurla Mandhata detachment system is reconstructed from thermokinematic modeling with Pecube of zircon (U-Th)/He and biotite and muscovite 40Ar/39Ar thermochronometric ages. -

Structural Evolution of the Gurla Mandhata Detachment System, Southwest Tibet: Implications for the Eastward Extent of the Karakoram Fault System

Structural evolution of the Gurla Mandhata detachment system, southwest Tibet: Implications for the eastward extent of the Karakoram fault system M.A. Murphy* An Yin P. Kapp² T.M. Harrison C.E. Manning Department of Earth and Space Sciences and Institute of Geophysics and Planetary Physics, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90095-1567, USA F.J. Ryerson Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, Livermore, California 94550, USA Ding Lin Guo Jinghui Institute of Geology and Geophysics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China ABSTRACT that they represent an evolving low-angle boundaries between tectonically distinct do- normal-fault system. 40Ar/39Ar data from mains are de®ned. Although several insightful Field mapping and geochronologic and muscovite and biotite from the footwall studies have been conducted to understand the thermobarometric analyses of the Gurla rocks indicate that it cooled below 400 8C processes controlling contemporaneous east- Mandhata area, in southwest Tibet, reveal by ca. 9 Ma. Consideration of the original west extension and distributed strike-slip major middle to late Miocene, east-west ex- depth and dip angle of the detachment fault faulting within the Tibetan plateau and north- tension along a normal-fault system, prior to exhumation of the footwall yields south shortening in the Himalayan thrust belt termed the Gurla Mandhata detachment total slip estimates between 66 and 35 km (Armijo et al., 1989; Molnar and Lyon-Caen, system. The maximum fault slip occurs across the Gurla Mandhata detachment -

Small Group Holiday Itinerary

Mount Kailash Trek, Tibet Journey from Nepal to Tibet, across the roof of the world, and trek with pilgrims on the famous Kailash Kora. Group departures See overleaf for departure dates Holiday overview Style Trek Accommodation Hotel, Tea Houses, Camping Grade Strenuous Duration 23 days from London to London Trekking / Walking days On trek: 12 days Min/Max group size 5 / 12. Guaranteed to run for 5 Trip Leader Local Leader Tibet Land only Joining in Chengdu, China Max altitude 5,630m/18,472ft, the Dolma La Pass, Day 17 Private Departures & Tailor Made itineraries available Watch related videos online: Mount Kailash Trek tel: +44 (0)1453 844400 fax: +44 (0)1453 844422 [email protected] www.mountainkingdoms.com Mountain Kingdoms Ltd, 20 Long Street, Wotton-under-Edge, Gloucestershire GL12 7BT UK Managing Director: Steven Berry. Registered in England No. 2118433. VAT No. 496 6511 08 Last updated: 17 March 2021 Departures Group departures 2021 Dates: Sat 17 Jul - Sun 08 Aug 2022 Dates: Sat 16 Jul – Sun 07 Aug 2023 Dates: Sat 15 Jul – Sun 06 Aug Group prices and optional supplements Please contact us on +44 (0)1453 844400 or visit our website for our land only and flight inclusive prices and single supplement options. No Surcharge Guarantee The flight inclusive or land only price will be confirmed to you at the time you make your booking. There will be no surcharges after your booking has been confirmed. Will the trip run? This trip is guaranteed to run for 5 people and for a maximum of 12. In the rare event that we cancel a holiday, we will refund you in full and give you at least 6 weeks warning. -

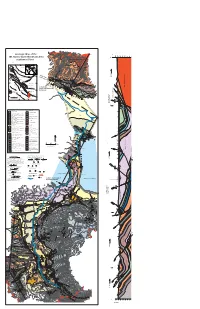

Geologic Map of the Mt. Kailas-Gurla Mandhata Area, Southwest Tibet

A'''' km Geologic Map of the 6 5 4 3 2 1 K-Tg 0 -1 -2 -3 -4 -5 -6 -7 -8 -9 -10 -11 -12 -13 -14 5600 Mt. Kailas-Gurla Mandhata Area, A'''' Kailas Magmatic Complex southwest Tibet 5400 5000 5800 K-Tg 78 E 81 E Mt. Kailas 6638 m Karakoram fault Kongur Shan Tibet Aksu-Rangkul Tarim Basin HIMALAYATIBET 30N fault 30N 5600 Muztagh Ata 38 N EPF Western IndochinaS. China INDOCHINA Karasu fault INDIA 5600 20N 5600 Kun Lun India Aksu-Mugab 12 strike-slip zone K-Tg Shan Tash Tv Karakoram Gurgan Tcg2 Batholith 70E 90E Q Karakax Fault Indus-Yalu 5800 36 N Tcg2 K2 36 N N 30 E Suture Zone 10 Gangdese Thrust Karakoram fault system Altyn Tagh Fault MKT reat Co Nanga Kc G u 5200 Karakoram n er Th 5400 Parbat 75 t rus Indus Molasse Batholith 18 t ISZ Kc Tcg2 Longmu Co-Gozha Co Fault sch Qal 34 N Tangtse sch Qal Tibetan Plateau 34 N High Himalaya 32 Domar-Wuijiang Thrust ss Mandong-Cuobei thrust northernmost Kailas Magmatic Complex Tso Morari Shiquanhe Tcg2 Shiquanhe Fault strand of the Karakoram 42 65 32 N Kc South Kailas 32 N fault system Ladakh-Gangdese STDS Thrust Kailas Conglomerate Batholith 50 40 30 Indus-Tsangpo Suture Zone Darchan Mt. Kailas 60 Main Boundary Thrust AWC South Kailas Thrust Lm Tcg1 Gurla Kc A''' Accretionary Wedge Complex 30 N Mandhata lm 0 100 200 30 N Qal sch Great Counter Thrust km Map Location 78 E 81 E ss AWC Yiema Fm.