Tacoma Historic School Survey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribute to Champions

HLETIC C AT OM M A IS M S O I C O A N T Tribute to Champions May 30th, 2019 McGavick Conference Center, Lakewood, WA FEATURING CONNELLY LAW OFFICES EXCELLENCE IN OFFICIATING AWARD • Boys Basketball–Mike Stephenson • Girls Basketball–Hiram “BJ” Aea • Football–Joe Horn • Soccer–Larry Baughman • Softball–Scott Buser • Volleyball–Peter Thomas • Wrestling–Chris Brayton FROSTY WESTERING EXCELLENCE IN COACHING AWARD Patty Ley, Cross Country Coach, Gig Harbor HS Paul Souza, Softball & Volleyball Coach, Washington HS FIRST FAMILY OF SPORTS AWARD The McPhee Family—Bill and Georgia (parents) and children Kathy, Diane, Scott, Colleen, Brad, Mark, Maureen, Bryce and Jim DOUG MCARTHUR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT AWARD Willie Stewart, Retired Lincoln HS Principal Dan Watson, Retired Lincoln HS Track Coach DICK HANNULA MALE & FEMALE AMATEUR ATHLETE OF THE YEAR AWARD Jamie Lange, Basketball and Soccer, Sumner/Univ. of Puget Sound Kaleb McGary, Football, Fife/Univ. of Washington TACOMA-PIERCE COUNTY SPORTS HALL OF FAME INDUCTEES • Baseball–Tony Barron • Basketball–Jim Black, Jennifer Gray Reiter, Tim Kelly and Bob Niehl • Bowling–Mike Karch • Boxing–Emmett Linton, Jr. and Bobby Pasquale • Football–Singor Mobley • Karate–Steve Curran p • Media–Bruce Larson (photographer) • Snowboarding–Liz Daley • Swimming–Dennis Larsen • Track and Field–Pat Tyson and Joel Wingard • Wrestling–Kylee Bishop 1 2 The Tacoma Athletic Commission—Celebrating COMMITTEE and Supporting Students and Amateur Athletics Chairman ������������������������������Marc Blau for 76 years in Pierce -

Spring 2017 Arches 5 WS V' : •• Mm

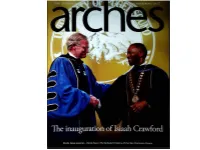

1 a farewell This will be the last issue o/Arches produced by the editorial team of Chuck Luce and Cathy Tollefton. On the cover: President EmeritusThomas transfers the college medal to President Crawford. Conference Women s Basketball Tournament versus Lewis & Clark. After being behind nearly the whole —. game and down by 10 with 3:41 left in the fourth |P^' quarter, the Loggers start chipping away at the lead Visit' and tie the score with a minute to play. On their next possession Jamie Lange '19 gets the ball under the . -oJ hoop, puts it up, and misses. She grabs the rebound, Her second try also misses, but she again gets the : rebound. A third attempt, too, bounces around the rim and out. For the fourth time, Jamie hauls down the rebound. With 10 seconds remaining and two defenders all over her, she muscles up the game winning layup. The crowd, as they say, goes wild. RITE OF SPRING March 18: The annual Puget Sound Women's League flea market fills the field house with bargain-hunting North End neighbors as it has every year since 1968 All proceeds go to student scholarships. photojournal A POST-ELECTRIC PLAY March 4: Associate Professor and Chair of Theatre Arts Sara Freeman '95 directs Anne Washburn's hit play, Mr. Burns, about six people who gather around a fire after a nationwide nuclear plant disaster that has destroyed the country and its electric grid. For comfort they turn to one thing they share: recollections of The Simpsons television series. The incredible costumes and masks you see here were designed by Mishka Navarre, the college's costumer and costume shop supervisor. -

Completed Facilities It Stands As One of the Top College Baseball Parks in the Country

2014 VANDERBILT BASEBALL Introduction 2013 Review 4 . .Media Information 56 . .Season Review 5 . Media Outlets/Broadcast Information 58 . Overall Season Statistics 6 . Quick Facts, Road Headquarters 59 . SEC Statistics 7 . 2014 Roster 60 . Miscellaneous Statistics 8 . Hawkins Field 62 . .Season Results 9 . Hawkins Field Records 63 . .SEC Recap 10 . 2014 Season Preview Vanderbilt History Commodore Coaching Staff 64 . .Commodore Letterwinners 14 . .Tim Corbin, Head Coach 66 . Commodore Coaching Records 18 . .Travis Jewett, Assistant Coach 68 . vs. The Nation 19 . Scott Brown, Assistant Coach 70 . .Yearly Results 20 . .Drew Hedman, Volunteer Assistant Coach 86 . .All-Time Individual Records 20 . Chris Ham, Athletic Trainer 87 . .All-Time Team Records 20 . David Macias, Strength & Conditioning 88 . Single-Season Records 20 . Drew Fann, Keri Richardson & Garrett Walker 89 . Career Records 90 . .Yearly Statistical Leaders 2014 Commodores 92 . .Yearly Team Statistics 21 . .Depth Chart, Roster Breakdown 94 . .SEC Tournament History 22 . Tyler Beede 95 . NCAA Tournament History 23 . Walker Buehler 96 . Commodores in the Majors 24 . Tyler Campbell 99 . Commodores in the Minors 25 . Vince Conde 100 . All-Time Commodores Drafted 26 . Will Cooper 27 . Tyler Ferguson Miscellaneous Information 28 . Carson Fulmer 102 . .SEC Composite Schedule 29 . Chris Harvey 104 . .Opponent Information 30 . .Brian Miller 107 . Nashville Information 31 . Jared Miller 32 . John Norwood 33 . T.J. Pecoraro 34 . .Adam Ravenelle 35 . .Steven Rice 36 . Kyle Smith 37 . .Dansby Swanson 38 . Xavier Turner 39 . Zander Wiel 40 . Rhett Wiseman 41 . Ben Bowden, Ro Coleman, Jason Delay, Karl Ellison 42 . .Tyler Green, Ryan Johnson, John Kilichowski, Aubrey McCarty 43 . Penn Murfee, Drake Parker, Bryan Reynolds, Nolan Rogers 44.......Jordan Sheffield, Luke Stephenson, Hayden Stone 46 . -

Vol. 44, No. 3, Arches Spring 2017

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Arches University Publications Spring 2017 Vol. 44, No. 3, Arches Spring 2017 University of Puget Sound Follow this and additional works at: https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/arches Recommended Citation University of Puget Sound, "Vol. 44, No. 3, Arches Spring 2017" (2017). Arches. 30. https://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/arches/30 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arches by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. a farewell This will be the last issue ofArches produced by the editorial team of Chuck Luce and Cathy Tollefson. On the cover: President Emeritus Thomas transfers the college medal to President Crawford. 4 arches spring 2017 Friends, Let us tell you a story. It’s a story about you. And it’s about a place that is what it is because of you. We hope you will forgive us for address- ing you collectively. There are 41,473 Puget Sound alumni, and while we’ve gotten to know a great many of you in the 18 or so years we’ve been editing this magazine, we still have a few to go. Cathy, you may have observed, is one of you. Class of 1983. She is also the parent of a 2017 graduate (woo-hoo, Olivia!), and will herself complete an M.Ed. this summer, them again, and meeting you for lunch in the and sorority reunions, sports-team reunions, so she’s lived the Logger life. -

Alumni Powwow

6J-n _ :v y, ,. " ~ ee1leae LibtarJ 1_0-;-0-/ 0he "Washington eState College Alumni Powwow 5-lomecoming ct1ssue CChis and CChat By Joe Caraher, '35 1k \Vhat little editorial comment is con tained herewith comes directly from Ta coma, \Vashington; \vhel'e this writer. absentee secretary of the W.S.c. Alumni WashiK9toH. ~tate Association, is doing his stint for Uncle Sam in the Air Corps as in contrast to hustling up a few doings in the interests cf the State College of \Vashington, its graduates and former students. alumKi POWWOW However it is a rare experience to be on the outside looking in, so to speak. be cause that has been the situation here. Getting mixed I,P with alumni activities, Vol: XXX Number 7 of course, is not a contagious proposition and not an interest which may be aband September, 1941 oned recklessly. On the other hand it is refreshing to see what keen enthusiasm is displayed by those Cougar die-hards who long since have departed from the Col Joe F. Caraher, '35, Secretary John Pitman, '39, Editor lege on the Hill. I speak with reference to the Pierce County Alumni club. comprised of some of the most radical backers of the Crimson SEPTEMBER CONTENTS and Gray I yet have had the pleasure of being thrown into direct contact with Page if I make myself clear. " Remember the Eleventh" 3 These folks in the City of Destiny and \Vhat's in store for returning Cougars at Homecoming. the surrounding territory are rabid. as a re!'lort of their wonderful picnic staged 4 with much fanfare on August 14, will Cougar Sports - testify. -

2. Stadium-Seminary Historic District

STADIUM-SEMINARY HISTORIC DISTRICT From the Stadium-Seminary Historic District nomination [Editor note: the following has not been cleaned up from a scan of the original document.} The Stadium-Seminary Historic District in the City of Tacoma is a residential neighborhood of substantial two and three-story homes developed between1888and1930. It is located northwest of the central business district on a high sloping site along a bluff overlooking Commencement Bay. With in the district the rear an early 400 buildings in an area encompassing the equivalent of 50 blocks. This neighborhood is distinguished by its exceptional quality and variety of architecture and its unusual continuity of period that is only rarely interrupted by more modern structures. Lawns and street trees (predominantly Horse Chestnut and Maple) contribute to a pleasing, overall impression of green space. Although his proposal was never used because of unforeseen political and economic considerations, Frederick Law Olmstead was commissioned to prepare a master plan for New Tacoma in 1873. The general concept of the City Beautiful Movement did influence the eventual layout of the Stadium-Seminary district when construction began 15 years later. It was a planned development on a fairly grand scale which is today most apparent in the extensive street plantings, orientation to vistas and distribution of open space. Wright Park and Garfield Park are located on opposite sides of the district, although the former is separated from the neighborhood by a major arterial. Annie Wright Seminary and an undeveloped ravine provide additional landscape features of contrasting texture - one carefully maintained, the other left in its natural state. -

Tacoma Chamber of Commerce

TACOMA CHAMBER OF COMMERCE Ms 40 BACKGROUND: Evolving through many incarnations, the Tacoma Chamber of Commerce has had a tremendous impact on the growth and development of the city. Little has been written on the history of the Tacoma Chamber of Commerce (apparently the chamber never wrote a history). However, this collection contains a wealth of information on the early history of the chamber of commerce. On the evening of January 22, 1884, a group of prominent Tacoma civic leaders and businessmen met at the Pierce County Courthouse to organize a chamber of commerce for the city. They appointed a committee to plan a permanent organization, a second meeting was convened on February 15, 1884, and articles of incorporation and a constitution of the Tacoma Chamber of Commerce Company were adopted. In this meeting a board of trustees was elected and a capital stock of $20,000 was raised with a membership cap of 200. By March, there were 58 members. During its first year, the chamber considered many questions concerning the development of Tacoma. The members recognized that their chief aim was to enhance the trade and commerce of the city. The board authorized the purchase of two lots on the corner of Pacific Avenue and South 12th Street, but the lots remained vacant until the Spring of 1885. On May 12, 1885, the board of trustees appointed a building committee, and ground was broken in July and the building was completed in November of 1885. The first meeting of the chamber in their new building was held in January 1886. -

Accredited Secondary Schools in the United States. Bulletin 1928, No. 26

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF EDUCATION BULLETIN, 1928, No. 26 ACCREDITED SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN THE UNITED STATES PREPARED IN THE DIVISION OF STATISTICS FRANK M. PHILLIPS CHIEF W ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS U.S.GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 20 CENTS PER COPY i L 111 .A6 1928 no.26-29 Bulletin (United States. Bureau of Education) Bulletin CONTENTS Page Letter of transmittal_ v Accredited secondary school defined_ 2 Unit defined_ 2 Variations in requirements of accrediting agencies_ 3 Methods of accrediting___ 4 Divisions of the bulletin_x 7 Part I.—State lists_ 8 Part II.—Lists of schools accredited by various associations-__ 110 Commission of the Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools of the Southern States_ 110 Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools of the Middle States and Maryland___ 117 New England College Entrance Certificate Board_ 121 North Central Association of Colleges and Secondary Schools_ 127 Northwest Association of Secondary and Higher Schools_ 141 in • -Hi ■: ' .= LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL Department of the Interior, Bureau of Education, Washington, D. C., October 26, 1928. Sir: Secondary education continues to grow and expand. The number of high-school graduates increases from year to year, and the percentage of these graduates who go to higher institutions is still on the increase. It is imperative that a list of those secondary schools that do a standard quantity and quality of work be accessible to students who wish to do secondary school work and to those insti¬ tutions to whom secondary school graduates apply for admission. -

Arches-Summer-2008.Pdf

arc contents Summer 2008 people and ideas ! 20 All Loggers On Deck ■Commencement Bay will be bristling with spars during I 'the July 4th weekend, and a number of Puget Sound alumnii I had a part in bringing the grand tall ships here ' 24 The Path Less Paddled Jonathan Blum ’06 and an international team of j (professional kayakers set out to paddle the endangered1 I rivers of South America___ ____ ____ 33 Classmates ■ -'V ,*££. USm news and notes on the cover Close-hauled and Tacoma bound. Story on page 20. Reuters/Corbis. 5 Zeitgeist In this issue: Tacoma’s conflicted relationship with the thispage Audrey Butler '11 and Jeff Uslan '10 of Cirque d'UPS in a May 3 | ! natural beauty that surrounds and defines it; from the' performance based on the Iroquois creation myth. Here they represent (Bus) Pass It Along blog, words to transit by; Tacoma the accumulating earth, upon which the fallen Sky Woman will soon has a poet laureate, and he’s a UPS prof; more campus |find a place to land. Photo by Ross Mulhausen. For more of Ross's * I _news and notes__ _ _ _ _ _ _ — pictures of campus events this past semester, turn to page 10. Alumni Association from the president Currents “I am haunted by waters.” This phrase from one of my favorite books, Norman Maclean’s A River Runs Through It, haunts me. Growing up at the ocean’s edge, the ebb and flow of tides always has both consoled and inspired me. I am drawn by the rhythm of waves, rising, cresting, breaking, and then rising again. -

W R Ight Park to Stadium Distric T

LK WA MA Why Walk? TACO If a daily fitness walk could be put in a pill, it would be one of the most popular prescriptions in the world. Walking can reduce the risk of 253 682 1734 many diseases – from heart attack and stroke to hip fracture and glau- downtownonthego.org coma. And of course, walking has significant positive implications for strength, mood, and weight loss. Downtown On the Go is a partnership of: TO STADIU Calories Burned per Hour* Tacoma-Pierce County Chamber • City of Tacoma • Pierce Transit RK M 110 lbs 125 lbs 150 lbs 175 lbs 200 lbs A D P I Strolling T S 100 cal 114 136 159 182 Sponsors T <2 mph H R Moderate Downtown: On the Go’s 2017 Walk Tacoma Kick-Off G I 175 199 239 278 318 I C 3 mph R Filled with historic places and buildings, the Wright Park walk takes T Brisk 200 227 273 318 364 you through the tranquility of this more than century old park and into W 3.5 mph the Stadium District (the densest residental area in Pierce County). Very Brisk 225 256 307 358 409 The walk returns to Wright Park for one last look at its most important 4.5 mph building, the W.W. Seymour Botanical Conservatory. Enjoy this Moderate relatively easy walk as you learn more about Tacoma’s unique past and Uphill 300 341 409 477 545 exciting present. 3mph *Source: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/physical_activity/index.html D P O A Why Walk Tacoma? W M Getting out of your office, hotel room, home, or car means you get NT G to see Tacoma up close and personal – and there is so much to OW IN see. -

SUMMER 2004 Tate Mmagazinea G a Z I N E

C ONNECTING W ASHINGTON S TATE U NIVERSITY, THE S TATE, AND THE W ORLD • SUMMER 2004 tate mmagazinea g a z i n e COVER Out of the Past, a Perennial Future for Eastern Washington STORY Shakespeare, Alhadeff, and Lewis and Clark SUMMER 2004 VOLUME 3, NUMBER 3 Washington tate magazine features Short Shakespeareans 23 by Pat Caraher • photos by Don Seabrook Sherry Schreck has built her life and reputation CONTENTS on her love of children and Shakespeare and her unbridled imagination. All that Remains 26 by Ken Olsen • photos by Greg MacGregor Nearly two-thirds of the Lewis and Clark Trail is under man-made reservoirs. Another one-quarter is buried under subdivisions, streets, parks, banks, and other modern amenities. Almost none of the original landscape is intact. No one appreciates this contrast like author and historian Martin Plamondon II, who has reconciled the explorers’ maps with the modern landscape. Full Circle 33 by Tim Steury Steve Jones and Tim Murray want to make the immense area of eastern Washington, or at least a good chunk of it, less prone to blow, less often bare, even more unchanging. The way they’ll do this is to convince a plant that is content to die after it sets seed in late summer that it actually wants to live. 38 Listening to His Heart by Beth Luce • photos by Laurence Chen 23 As a student at WSU in the late ’60s, Ken Alhadeff questioned authority with zeal. “I was part of a group of folks that marched down the streets of Pullman to President 33 Terrell’s house with torches, demanding that the Black Studies Program not be eliminated. -

COVER STORY Tacoma's Lincoln High School in 1938, the Choir Was

COLUMBIA THE MAGAZINE OF NORTHWEST HISTORY ■ SPRING 2018 COVER STORY Tacoma’s Lincoln High School In 1938, the choir was Off To St. Louis! Meet the Godfather of the Tri-Cities Washington’s Woodstock of the McCarthy Era The Washington State History Museum offers event rentals tailored to suit your specific needs. From small business meetings and luncheons to auditorium events and receptions suitable for 20 to 350 guests. Visit us online at wWashintonHistory.org/visit/wshm/rentalsashingtonHistory.org/visit/wshm/rentals or call 253-798-5891 for details. ONE-WEEK July 9-13: Museum Mania CAMPS July 16-20: Washington Explorers Each with its own theme! July 23-27: Washington’s History Mysteries Registration is open! www.WashingtonHistory.org/summercamps 1911 Pacific Avenue, Tacoma, WA CONTENTS COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History A quarterly publication of the VOLUME THIRTY-TWO, NUMBER ONE ■ Feliks Banel, Editor Theresa Cummins, Graphic Designer FOUNDING EDITOR 4 John McClelland Jr. (1915–2010) ■ COVER STORY OFFICERS President: Larry Kopp, Tacoma 4 Off to St. Louis! by Kim Davenport & Rafael Saucedo Vice-President: Robert C. Carriker, Spokane A cross-country trip by Tacoma high school students during the Great Vice-President: Ryan Pennington, Woodinville Depression was made possible by a supportive community and a beloved Treasurer: Alex McGregor, Colfax choir director. Secretary/WSHS Director: Jennifer Kilmer EX OFFICIO TRUSTEES Jay Inslee, Governor Chris Reykdal, Superintendent of Public Instruction Kim Wyman, Secretary of State BOARD OF TRUSTEES Sally Barline, Lakewood Natalie Bowman, Tacoma Enrique Cerna, Seattle Senator Jeannie Darneille, Tacoma David Devine, Tacoma Suzie Dicks, Belfair John B.