COMMEMORATION Reflections on the Meaning of a Tragedy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Intervention De Mme La Maire De Paris Suite À L'attentat Perpétré Le 7 Janvier 2015

Intervention de Mme la Maire de Paris suite à l'attentat perpétré le 7 janvier 2015. 09/01/2015 Par Mme Anne HIDALGO - Maire de Paris Seul le prononcé fait foi Monsieur le maire honoraire de Paris, Mesdames et Messieurs les présidents de groupe, Mes chers collègues, Mesdames et Messieurs les journalistes, les familles, les amis et collègues des victimes, Messieurs les représentants de l’État, Dans des circonstances d’une extrême gravité, nous sommes réunis ce matin pour témoigner de l’union sacrée des Parisiens - union sacrée pour honorer nos morts, union sacrée pour défendre notre liberté, et union sacrée pour assurer notre sécurité. Je veux remercier mes collègues maires de France et du monde entier qui nous ont manifesté leur affection et leur solidarité. Mes premiers mots vont aux douze femme et hommes qui ont payé de leur vie le prix de notre liberté. Frédéric Boisseau Franck Brinsolaro Jean Cabu Elsa Cayat Stéphane Charbonnier alias Charb Philippe Honoré Bernard Maris alias oncle Bernard Ahmed Merabet Mustapha Ourrad Michel Renaud Bernard Verlhac alias Tignous Georges Wolinski Ces noms font dorénavant partie de la mémoire vivante de Paris. Chacun d’entre eux est celui d’un homme et d’une femme de paix et en même temps d’un partisan de la liberté. Chacun d’entre eux est celui d’un héros tombé en défendant les valeurs les plus profondes et les plus essentielles de notre humanité. Chacun d’entre eux enfin est celui d’un fils, d’un père, d’un frère, d’un ou d’une amie, d’un ou d’une collègue. -

Du Sel À L'huître

Du sel à l’huître BULLETIN MUNICIPAL PRINTEMPS 2015 Transition énergétique > p 7 dans ce numéro... Le mot du maire .................................p. 3 Terre de maraîchage > p 9 Vie municipale ............................p. 4 à 16 Comment ça marche : la délibération ....p. 4 Le Fief Melon, où en est-on ? ..............p. 5 Urbanisme : La place des défunts .........p. 6 Finances .........................................p. 6 Économie : transition énergétique ........p. 7 Éducation ........................................p. 8 Agriculture ......................................p. 9 Travaux ......................................... p. 10 Arboristes grimpeurs Arboristes grimpeurs ................ p. 10 et 11 > p 10 et 11 Sentier des naissances ..................... p. 12 Affaires sociales ..................... p. 13 et 14 Retour en images sur Noël ................ p. 15 La page de l’opposition .................... p. 16 Marche blanche pour Charle Hebdo ................cahier central Retour en images > p 15 Vie locale ................................. p. 17 à 23 Parcours de vie : Carla Arbez ............. p. 17 La migration des cabanes ................. p. 18 L’office de tourisme du futur ............. p. 19 Dolusiens du monde ........................ p. 19 Économie .............................. p. 20 et 21 Les eaux pluviales ........................... p. 21 Zoom sur Jonathan Musereau ..... p. 22 à 23 Directeur de la publication : Vie intercommunale ................... p. 24 à 26 Grégory Gendre Le «non-hommage» à Charlie Hebdo La recette de -

Minute of Silence for the Victims of the Attacks Against the Charlie Hebdo Magazine, France's Police Forces and the Jewish Supermarket

European Parliament President Martin Schulz Minute of silence for the victims of the attacks against the Charlie Hebdo magazine, France's police forces and the Jewish supermarket Speeches Strasbourg 12-01-2015 Martin Schulz Dear Colleagues, Philip Braham Franck Brinsolaro Frédéric Boisseau Jean Cabut Elsa Cayat Stephane Charbonnier Yohan Cohen Yoav Hattab Philippe Honoré Clarissa Jean-Philippe Bernard Maris Ahmed Merabet Mustapha Ourrad Michel Renaud François-Michel Saada Bernard Verlhac and Georges Wolinski. These are the names of the seventeen victims of the attack against Charlie Hebdo, against the police and against the Jewish supermarket last week. On behalf of the European Parliament, I express our sincere condolences to their families and their friends. I also wish the injured a speedy recovery. Dear Colleagues, Seventeen people died. These cartoonists, these journalists, these policemen, these employees, these Jewish citizens died because they defended and because they embodied what fanatics do not want: Criticism. Humor. Satire. Freedom of expression. Our life in a single community, irrespective of different opinions and confessions. Our right to live together and in safety. To put it simply: Our freedom. Minute of silence for the victims of the attacks against the Charlie Hebdo magazine, France's police forces and the 1/ Jewish supermarket 2 European Parliament President Martin Schulz These attacks are an attack against all of us. It is up to us to respond. There are many dangers: We must not minimise our freedom of thought or revise downward our European values in the face of violence and Kalashnikovs. We must not let fear, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and hatred of others eat away the values that define us: the freedom of the press and freedom of expression, tolerance and mutual respect. -

Le 11-Septembre Français

Vendredi 9 janvier 2015 71e année No 21766 2,20 € France métropolitaine www.lemonde.fr ― Fondateur : Hubert BeuveMéry LE 11-SEPTEMBRE FRANÇAIS ENQUÊTE ÉMOTION CARICATURES DÉBATS RÉCIT 100 000 personnes LA TRAQUE DEUIL NATIONAL ET L’HOMMAGE BHL, VILLEPIN : « ILS ONT TUÉ ont participé à des manifestations (ici à DES DEUX FRÈRES RASSEMBLEMENTS DES DESSINATEURS RÉSISTER À L’ESPRIT “CHARLIE HEBDO” » Toulouse, mercredi). ULRICH LEBEUF/MYOP DJIHADISTES SPONTANÉS DU MONDE ENTIER DE GUERRE POUR « LE MONDE » LE REGARD DE PLANTU sassiné lâchement des journalis teurs » qui osaient moquer leur tes, des dessinateurs, des em Prophète. L’équipe de Charlie ployés ainsi que des policiers Hebdo n’avait pas reculé, pas LIBRES, chargés de leur protection. cédé, pas cillé. Chaque semaine, Douze morts, exécutés au fusil armée de ses seuls crayons, elle DEBOUT, d’assaut, pour la plupart dans les continuait son combat pour la li ENSEMBLE locaux mêmes de ce journal libre berté de penser et de s’exprimer. et indépendant. Certains ne cachaient pas leur par gilles van kote Et, au milieu du carnage, victi peur, mais tous la surmontaient. mes de cette infamie, des collè Soldats de la liberté, de notre li gues, des camarades : Cabu, berté, ils en sont morts. Morts Charb, Honoré, Tignous, Wo pour des dessins. motion, sidération, mais linski, ainsi que l’économiste A travers eux, c’est bien la li aussi révolte et détermi Bernard Maris. Depuis des an berté d’expression – celle de la E nation : les mots peinent nées, des décennies, ils résis presse comme celle de tous les à exprimer l’ampleur de l’onde taient par la caricature, l’hu citoyens – qui était la cible des de choc qui traverse la France, au mour et l’insolence à tous les fa assassins. -

Junger to Give Keynote at Annual Scholars Luncheon

THE MONTHLY NEWSLETTER OF THE OVERSEAS PRESS CLUB OF AMERICA, NEW YORK, NY • January 2015 Junger to Give Keynote at Annual Scholars Luncheon be, a former Wall Street EVENT PREVIEW lawyer who, as acting By Jane Reilly CEO for the Wash- Award-winning journalist, film- ington Post Company, maker and author Sebastian Junger had a special apprecia- will be the keynote speaker at the tion for journalism and annual OPC Foundation Scholarship journalists. (See page 8 Luncheon on Friday, Feb. 20, 2015, for more details.) at the Yale Club. At the event, the “In my 20 years of Foundation will award a combina- serving as president of tion of scholarships and fellowships the Foundation,” said Hetherington Tim to 15 graduate and undergraduate OPC Foundation Presi- Sebastian Junger poses for a photo taken by his college students aspiring to become dent Bill Holstein, “I friend Tim Hetherington, who was killed while on foreign correspondents. have seen the impor- assignment in Libya in 2011. The winning recipients are from tance of our mission be- we have seen in Syria and Yemen.” Columbia University, New York come more critical with each passing Given the perilous climate, Hol- University, Northwestern Univer- year. News media organizations have stein said that Junger’s selection sity, Oxford University (England), pulled back on maintaining their own as keynote speaker is “the perfect Tufts University, University of Cal- networks of seasoned correspondents choice for these troubled times.” ifornia-Berkeley, University of Tul- and are relying more heavily than Besides being among the foremost sa, and Yale University. For the first ever on young correspondents like freelance foreign correspondents of time this year, the Foundation will our winners. -

Procès Des Attentats Des 7, 8 Et 9 Janvier 2015 Devant La Cour D’Assises Spéciale, Au Tribunal Judiciaire De Paris

Procès des attentats des 7, 8 et 9 janvier 2015 Devant la cour d’assises spéciale, au Tribunal judiciaire de Paris ****** Le mercredi 2 septembre 2020, s’ouvre devant la cour d’assises spécialement composée de Paris, le procès des attentats de janvier 2015. Les accusés sont poursuivis sous différentes qualifications criminelles telles que « complicité d’entreprise terroriste », « association de malfaiteurs terroriste criminelle », « association de malfaiteurs criminelle » et « acquisition, détention et cession d’armes de catégorie A et B » pour les faits commis les 7, 8 et 9 janvier 2015 à Paris, Montrouge et Dammartin-en-Goële. Les terroristes auteurs des attaques, Saïd KOUACHI, Mohamed KOUACHI et Amedy COULIBALY, sont décédés lors d’assauts des forces de l’ordre. Les accusés sont poursuivis pour leurs responsabilités dans la préparation et la réalisation de ces attentats ayant marqué la société française par leur violence et leur envergure. ****** En raison de la durée de l’audience et de l’intérêt des débats pour les victimes et le public, l’AfVT propose un compte rendu hebdomadaire exhaustif afin de connaitre la teneur du procès chaque semaine. Ce compte rendu est élaboré à partir des notes prises par l’AfVT, association de victimes et d’aide aux victimes, partie civile au procès. Eu égard au débit de parole, la prise de notes ne saurait refléter l’intégralité des propos. Seul le prononcé fait foi. 1 Evènements marquants de la semaine Compte rendu de la semaine du 7 au 11 septembre 2020 – Semaine n°2 ♦ Le témoignage des victimes et des Lundi 7 septembre 2020 – Jour 4 : proches du 7 janvier : Des déclarations fortes et justes dans un Cette journée concernera l’enquête ainsi que la description but d’hommage et de vérité. -

TALLINN UNIVERSITY of TECHNOLOGY School of Business

TALLINN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY School of Business and Governance Department of Law Xhensila Gjaci CHARLIE HEBDO CARTOONS CASE IN EUROPE: DANGEROUS JOURNEYS AT THE EDGES OF FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION Master Thesis LAW, European Union and International Law Supervisor: EvhenTsybulenko, Senior Lecturer Tallinn 2020 I hereby declare that I have compiled the thesis/paper independently and all works, important standpoints and data by other authors have been properly referenced and the same paper has not been previously presented for grading. The document length is 19094 words from the introduction to the end of the conclusion. Xhensila Gjaci …………………………… (signature, date) Student code: 146963HAJM Student e-mail address: [email protected] Supervisor: Evhen Tsybulenko, Senior Lecturer: The paper conforms to requirements in force …………………………………………… (signature, date) Chairman of the Defence Committee: Permitted to the defence ………………………………… (name, signature, date) TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 5 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 6 INTRODUCTION 7 1. ROOTS OF A TRAGEDY 10 1.1. Charlie Hebdo Attack 10 1.1. Genesis of the case 13 1.2. Charlie Hebdo and it place in French Journalism 19 1.3. The nature of the published cartoons of Prophet Muhammed 22 2. FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION 25 2.1. Short history 25 2.2. Instruments regulating freedom of expression 26 2.3. Article 10 of European Convention on Human Rights 29 2.3.1. More about the categories of expression 30 2.3.2. States obligation 32 2.3.3. Special role of media and press 34 2.3.4. Second paragraph of Article 10 36 3. ANALYSING OF THE CASE IN THE LIGHT OF THE PRINCIPLES OF DEMOCRACY 38 3.1. -

Antisemitism in France

Service de Protection de la Communauté Juive Jewish Community Security Service ! 2014 Report on Antisemitism in France Source of statistical data : Ministry of Interior and SPCJ" www.antisemitisme.fr This report can be downloaded in French, English and Hebrew at www.antisemitisme.fr This report was written with the support of# the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah (FMS) ! " The 2014 report on# Antisemitism in France# is dedicated to the memory# of the victims of the terror# attacks on January 7, 8,# and 9, 2015. ! Victims of the attacks committed on 7 January 2015 in Paris # in the Charlie Hebdo newsroom Frédéric Boisseau ; Franck Brinsolaro ; Jean Cabut, aka Cabu ; Elsa Cayat ; Stéphane Charbonnier, aka Charb ; Philippe Honoré, aka Honoré ; Bernard Maris ; Ahmed Merabet ; Mustapha Ourrad ; Michel Renaud ; Bernard Verlhac, aka Tignous ; Georges Wolinski ! Victim of the attack committed on 8 January 2015# in Montrouge (92) Clarissa Jean-Philippe ! Victims of the attack committed on 9 January 2015# in the kosher supermarket at the Porte de Vincennes Philippe Braham ; Yohan Cohen ; Yoav Hattab ; François-Michel Saada REPORT ON ANTISEMITISM# IN FRANCE IN 2014" ANTISEMITISM IN FRANCE IN 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents 7 SPCJ 9 Eric de Rothschild, SPCJ President 11 Our methodology 13 1. Assessment and analyses 15 1.1 Assessment and analyses 17 1.2 Recap chart of Antisemitic acts recorded in 2014 19 1.3 Antisemitism In France in 2014 21 1.4 Antisemitic acts recorded in France from 1998 to 2014 27 1.5 Racism and antisemitism in 2014 31 1.6 Geographic breakdown of antisemitic acts in 2014 37 2. -

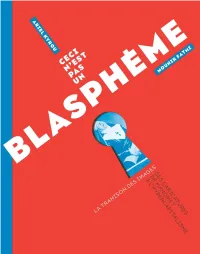

Ceci N'est Pas Un Blasphème

« as touche au prophète. Pas touche au Coran. Pas touche à la Bible. Pas touche au Christ en croix. pPas touche à la famille. Pas touche au cache-sexe. Pas touche aux marques. Pas touche à la mémoire sanctiiée. Ceci n’est pas un blasphème est né d’un mélange d’incompréhension et de colère, du sentiment d’un relux : comme si la société répondait à la vague de libertés du net, à l’évolution des mœurs et aux prouesses médicales de la technoscience par une marée réactionnaire inédite. » Artiste, mounir fatmi Ceci n’est pas un blaphème interroge le blasphème a exposé dans des musées, biennales, sous toutes ses coutures, partant de ses dimensions galeries et centres historiques pour mieux explorer sa réalité contem- d’art du monde entier. Certaines de ses œuvres poraine, de la religion au capitalisme en passant par à portée politique la science. Il est né d’un dialogue entre un artiste et symbolique ont été censurées, en particulier parfois accusé de blasphème, mounir fatmi, et à l’Institut du monde un essayiste hérétique de notre nouveau monde arabe ou au Printemps de Septembre à numérique, Ariel Kyrou. Toulouse. Se croisent ainsi : Dieudonné et les acteurs Ariel Kyrou est l’auteur de la Manif pour tous, mais aussi Charlie Hebdo, de plusieurs essais, parmi lesquels Révolutions le Caravage, ORLAN, Nike, Daesh, Michel-Ange, du Net, Google God, les Pussy Riot, Brian Eno, sainte Julie de Corse, ABC-Dick (inculte) et Paranoictions les alévis, Apple, Toscani, les frères du Libre-Esprit, (Climats). le Coran, Michel Houellebecq, Salman Rushdie, les Yes Men, Oreet Ashery, George Grosz, la lapine luo Alba, Alain Soral, la PMA, Marcel Duchamp, Laibach, Andres Serrano et bien d’autres. -

Organization for Security and Co-Operation in Europe the Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe The Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović Communique 01/2015 Communique on freedom of expression and freedom of the media as a vital condition for tolerance and nondiscrimination The world is mourning the horrific terrorist attack on the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in which 12 people were murdered and several people wounded. Eight of the victims were Charlie Hebdo staff: Stéphane Charbonnier aka Charb, Jean Cabut aka Cabu, Bernard Verlhac, aka Tignous, Georges Wolinski, Bernard Maris, aka Oncle Bernard, Philippe Honoré, aka Honoré, Elsa Cayat and Mustapha Ourrad. This is the worst single attack against journalists in the OSCE region since the establishment of this Office. It is encouraging that the political leaders from all corners of the world and leaders of major religious communities condemned this brutal cold-blooded murder. Condemnation is not sufficient. Action speaks louder than words. I call on all political leaders to honor the memory of the victims by improving the safety of journalists and ensuring that freedom prevail. The conclusions from the roundtable “Freedom of expression for tolerance and non- discrimination,” organized by my Office on 18 December 2014, have unfortunately become even more relevant today. I hereby reiterate some of the main issues: The space for discussion and debate has transcended national boundaries and become global. Speech is also more abundant than ever. Opinions and thoughts that were expressed only within small communities and walled gardens now can reach a global audience in a matter of seconds. We need to avoid a vision of free speech as something opposite to the prevention of intolerance or other threats to social cohesion. -

Début De L'avant-Propos "Pourquoi Rééditer Ce Livre ?"

Voici venu le temps d'affirmer, contre les économistes, que l'inutile crée de l'utilité, que “ la gratuité crée de la richesse, que l'intérêt ne peut exister sans le désintéressement. Bernard Maris, Antimanuel d’économie – 2. Les cigales (Bréal, 2006)” Le jour où la souffrance ne sera plus vue comme une obscénité et que la violence ne “ sera plus vue comme une toute-puissance fascinante là où elle n'est que le témoignage d'une impuissance, alors se profilera l'horizon de la liberté. Elsa Cayat, Noël, ça fait vraiment chier ”! – Sur le divan de Charlie Hebdo (Les Échappés-Charlie Hebdo, 2015) Pourquoi rééditer ce livre ? Le 7 janvier 2015, alors que je fais le tour des nouvelles de la mi-journée, quelques mots font irruption sur mon écran : Wolinski, Cabu… assassinés ! Ces impertinents débonnaires, ces rieurs impénitents que j’avais laissé vieillir en les perdant un peu de vue, comme s’il serait toujours temps de les lire et de rire avec eux… Ma sidération est telle que, d’abord, je ne vois pas les autres noms, mais seulement ce fait brutal, impensable. Plus tard, j’interrogerai des artistes et ils me décriront le même choc. Ils me diront aussi que leur seul recours pour surmonter l’insupportable fut de sortir dans la rue pour y peindre, alors même qu’au fil des heures l’horreur s’ajoutait à l’horreur : on nommait d’autres morts, une policière était abattue dans une rue de Montrouge, des juifs à leur tour étaient pris en otage et tués, alors qu’ils faisaient tranquillement leurs courses… Mémorial de la rue Nicolas- Appert, Paris 11e, janvier 2015. -

Research Report Establish International Cooperation to Stop The

Ferney-Voltaire Model United Nations 2021 Research Report COMMITTEE : Security Council ISSUE : Establish international cooperation to stop the development of terrorist networks on the Internet. CHAIRS : Galileo GREY, Leta JAGOE Establish international cooperation to stop the development of terrorist networks on the Internet. INTRODUCTION The relationship between terrorism and the internet is significant. Indeed, the use of the Internet has immensely benefited modern society, especially in the aspect of facilitated communication and effortless access to numerous sources of information. However, terrorist groups worldwide have taken advantage of this effective means of communication to spread their messages to wider audiences across the globe. The manipulation of the Internet to recruit terrorists and incite them to commit acts of terrorism has allowed terrorists to strengthen their movements internationally. The mass media’s coverage of acts of terrorism plays a part in the effectiveness of the use of the Internet as a tool used to spread terrorism. The censorship of acts of terrorism by the mass media may encourage more drastic acts, but mass media coverage of these acts is also the primary goal of many terrorist organizations. KEY WORDS Terrorism : Terrorism is the illegal use of violence and intimidation during peacetime, or hostility towards non-combatants in the case of a war, commonly with religious or political aims. Radicalism : Radicalism consists of views and opinions that are extreme, and beyond the norm of their era. Cyberterrorism : Cyberterrorism is the use of the Internet with the goal of organizing acts of violence that engender injuries or deaths. Its purpose is to obtain political or religious achievements.