The Physical Structure of Tabriz in Shah Tahmasp Safavid's Era Based on Matrakci Miniature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14 Days Persia Classic Tour Overview

Tour Name: 14 Days Persia Classic Tour Tour Code: OT1114001 Tour Duration: 14 Days and 13 Nights Tour Category: Discovery / Cultural Tour Difficulty: 2 Tour Tags: Classic Tour Tour Best Date: 12 months Tour Services Type: 3*/4* / All-inclusive Tour Destinations: Tehran/Kashan/Esfahan/Yazd/Shiraz/Kerman Related tours code: Number ticket limits: 2-16 Overview: Landing to Persia, Iran is a country with endless history and tradition and you explore both ancient Persia and modern Iran. Our Persia Classic Tour program includes the natural and historical attractions old central parts of Iran. In this route, we will visit cities like Tehran, Kashan, Isfahan, Yazd, Shiraz and finally Kerman. Actually, in most of these areas, living in warm and dry areas has been linked with history and has shaped the lifestyle that is specific to these areas. Highlights: . It’s a 14 days Iran classic discovery and cultural tour. The tour starts and ends in Tehran. In between, we visit 6 main cities and 17 amazing UNESCO world heritage site in Iran. Visit amazing UNESCO world heritage sites in Iran Tour Map: Tour Itinerary: Landing to PERSIA Welcome to Iran. To be met by your tour guide at the airport (IKA airport), you will be transferred to your hotel. We will visit Golestan Palace* (one of Iran UNESCO World Heritage site) and grand old bazaar of Tehran (depends on arrival time). O/N Tehran Magic of Desert (Kashan) Leaving Tehran behind, on our way to Kashan, we visit Ouyi underground city. Then continue to Kashan to visit Tabatabayi historical house, Borujerdiha/Abbasian historical house, Fin Persian garden*, a relaxing and visually impressive Persian garden with water channels all passing through a central pavilion. -

A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today

Volume: 8 Issue: 2 Year: 2011 A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today Ercan Karakoç Abstract After initiation of the glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring) policies in the USSR by Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union started to crumble, and old, forgotten, suppressed problems especially regarding territorial claims between Azerbaijanis and Armenians reemerged. Although Mountainous (Nagorno) Karabakh is officially part of Azerbaijan Republic, after fierce and bloody clashes between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, the entire Nagorno Karabakh region and seven additional surrounding districts of Lachin, Kelbajar, Agdam, Jabrail, Fizuli, Khubadly and Zengilan, it means over 20 per cent of Azerbaijan, were occupied by Armenians, and because of serious war situations, many Azerbaijanis living in these areas had to migrate from their homeland to Azerbaijan and they have been living under miserable conditions since the early 1990s. Keywords: Karabakh, Caucasia, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Ottoman Empire, Safavid Empire, Russia and Soviet Union Assistant Professor of Modern Turkish History, Yıldız Technical University, [email protected] 1003 Karakoç, E. (2011). A Brief Overview on Karabakh History from Past to Today. International Journal of Human Sciences [Online]. 8:2. Available: http://www.insanbilimleri.com/en Geçmişten günümüze Karabağ tarihi üzerine bir değerlendirme Ercan Karakoç Özet Mihail Gorbaçov tarafından başlatılan glasnost (açıklık) ve perestroyka (yeniden inşa) politikalarından sonra Sovyetler Birliği parçalanma sürecine girdi ve birlik coğrafyasındaki unutulmuş ve bastırılmış olan eski problemler, özellikle Azerbaycan Türkleri ve Ermeniler arasındaki sınır sorunları yeniden gün yüzüne çıktı. Bu bağlamda, hukuken Azerbaycan devletinin bir parçası olan Dağlık Karabağ bölgesi ve çevresindeki Laçin, Kelbecer, Cebrail, Agdam, Fizuli, Zengilan ve Kubatlı gibi yedi semt, yani yaklaşık olarak Azerbaycan‟ın yüzde yirmiye yakın toprağı, her iki toplum arasındaki şiddetli ve kanlı çarpışmalardan sonra Ermeniler tarafından işgal edildi. -

Treasures of Iran

Treasures of Iran 15 Days Treasures of Iran Home to some of the world's most renowned and best-preserved archaeological sites, Iran is a mecca for art, history, and culture. This 15-day itinerary explores the fascinating cities of Tehran, Shiraz, Yazd, and Isfahan, and showcases Iran's rich, textured past while visiting ancient ruins, palaces, and world-class museums. Wander vibrant bazaars, behold Iran's crown jewels, and visit dazzling mosques adorned with blue and aqua tile mosaics. With your local guide who has led trips here for over 23 years, be one of the few lucky travelers to discover this unique destination! Details Testimonials Arrive: Tehran, Iran “I have taken 12 trips with MT Sobek. Each has left a positive imprint on me Depart: Tehran, Iran —widening my view of the world and its peoples.” Duration: 15 Days Jane B. Group Size: 6-16 Guests "Our trip to Iran was an outstanding Minimum Age: 16 Years Old success! Both of our guides were knowledgeable and well prepared, and Activity Level: Level 2 played off of each other, incorporating . lectures, poetry, literature, music, and historical sights. They were generous with their time and answered questions non-stop. Iran is an important country, strategically situated, with 3,000+ years of culture and history." Joseph V. REASON #01 REASON #02 REASON #03 MT Sobek is an expert in Iran Our team of local guides are true This journey exposes travelers travel, with over five years' experts, including Saeid Haji- to the hospitality of Iranian experience taking small Hadi (aka Hadi), who has been people, while offering groups into the country. -

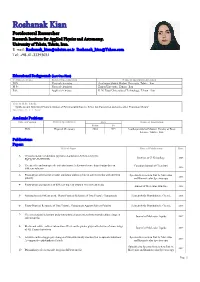

Roshanak Kian Postdoctoral Researcher Research Institute for Applied Physics and Astronomy, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran

Roshanak Kian Postdoctoral Researcher Research Institute for Applied Physics and Astronomy, University of Tabriz, Tabriz, Iran. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Tel: +98-41-33393031 Educational Background: (Last One First) Certificate Degree Field of Specialization Name of Institution Attended PhD Physical chemistry Azarbaijan Shahid Madani University, Tabriz - Iran M.Sc. Physical chemistry Zanjan University, Zanjan - Iran B.Sc. Applied chemistry K. N. Toosi University of Technology, Tehran - Iran Title of M.Sc. Thesis: “ Synthesis and Structural Characterization of Pyridinocalix(4)arene Silver Ion Complexes and some other Transition Metals” Supervisors: Dr. A. A. Torabi Academic Positions: Title of Position Field of Specialization Date Name of Institution From To PhD Physical Chemistry 2010 2015 Azarbaijan Shahid Madani- Faculty of Basic Science, Tabriz - Iran. Publications: Papers: Title of Paper Place of Publication Date 1- Crystal structure of dichloro (pyridine-2-aldoxime-N,N)mercury(II): JOURNAL OF Z. Kristallogr 2005 HgCl2(NC5H4CHNOH) 2- The specific and non-specific solvatochromic behavior of some diazo Sudan dyes in Canadian Journal of Chemistry 2015 different solvents 3- Photo-physical behavior of some antitumor anthracycline in solvent media with different Spectrochimica Acta Part A: Molecular 2014 polarity and Biomolecular Spectroscopy 4- Photo-physical properties of different types of vitamin A in solvent media Journal of Molecular Structure 2015 5- Solvatochromic Effects on the Photo-Physical -

Resumes-RS-04 AB

Awards and Achievements • Winner of the Farabi International Festival (on Humanities And Islamic Studies), Third prize in education and psychology division (2012) • Outstanding Researcher at Tarbiat Modarres University (2012) • Winner of National Outstanding Thesis/Doctoral Dissertation Advisor Award by Academic Center for Education, Culture and Research (ACEVR) /Iran (2010) • Translator of the Worthy of Appreciation book on 8th National Quarterly Best Book award and 7th Annual Islamic Republic of Iran Best Book Award for the: Forms of Curriculum Inquiry (2009) • Outstanding Faculty Award at the Humanities Department of Tarbiat Modarres University (2009) • Outstanding Faculty Award, Ministry of Science, Research and Technology/Iran (2008) • Outstanding Faculty Award at Tarbiat Modarres University/Iran (2004) • Outstanding dissertation advisor award, 5th National Ferdowsi Festival, Ferdowsi University, Mashhad, Iran (2002) Publications I. Books 1. Mehrmohammadi, M.; Kian, M. (2018). Art Curriculum and Teaching in Education. Tehran: SAMT Publishing House. 2. Mehrmohammadi, M. et al. (2014). Curriculum: Theories, Approaches and Perspectives (3rd Edicion). Tehran: SAMT Publishing House. 3. Joseph, P. B. (2014). Cultures of Curriculum. Translated into Farsi by Mahmoud Mehrmohammadi. Tehran: SAMT Publishing House. 4. Mehrmohammadi, M. et al. (2013). An introduction to Teaching in higher education; Towards Faculties as pedagogic researchers. Tehran: Tarbiat Modarres University Publishing. 5. Mehrmohammadi, M. (2013). Speculative Essays in Education. Tehran: Tarbiat Modarres University Publishing House. 6. Mehrmohammadi, M. (2008). Rethinking Teaching – Learning Process and Teacher Education, with Revisions. Tehran: Madrese Publishing House. 7. Mehrmohammadi, M. (Chief Editor) et al. (2008) Forms of Curriculum Inquiry (New Edition). Tehran: Translated into Farsi. SAMT Publishing House. 8. Mehrmohammadi, M. (2004). Arts Education as General Education. -

Peyman Ghobadi-Azbari

Peyman Ghobadi-Azbari - Ph.D candidate of Biomedical Engineering, Shahed University, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Tehran, Iran. - Iranian National Center for Addiction Studies (INCAS), Neurocognitive Laboratory (NCL), Tehran, Iran. Phone: +98 911 9371985 Date and Place of Birth: 1986, Tehran Nationality: Iranian Email: [email protected] [email protected] Languages: Persian, English Personal Statement: I was admitted to the Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) in 2011 as a biomedical engineering student after passing the MSc national university entrance exam with a rank of 8. I became interested in the neuronavigation systems in general and computational modelling and brain image processing in particular. I received my first grant as a biomedical engineering student in 2012 and published my first paper on the “Design a new hybrid system for patient dose reduction in image-guided surgery using a tracked mobile C-arm”. I graduated from TUMS with honors in 2014. My dissertation was on the design a novel structure “Stereo-C-arm”. Immediately, I started to work at the Research Center for Science and Technology in Medicine (RCSTIM). As the researcher of Intelligent Surgical System lab, I found great opportunities to explore the neuronavigation systems in order to improve clinical outcomes for neurosurgical procedures and therapies. To extend my knowledge, I was admitted to the Shahed University in 2015 as a biomedical engineering student after passing the PhD national university entrance exam with a rank of 23 and do my thesis project on the development and integration of non-invasive transcranial brain stimulation techniques with neuroimaging approaches for use in the domain of obesity and addiction. -

Turkomans Between Two Empires

TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) A Ph.D. Dissertation by RIZA YILDIRIM Department of History Bilkent University Ankara February 2008 To Sufis of Lāhijan TURKOMANS BETWEEN TWO EMPIRES: THE ORIGINS OF THE QIZILBASH IDENTITY IN ANATOLIA (1447-1514) The Institute of Economics and Social Sciences of Bilkent University by RIZA YILDIRIM In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY BILKENT UNIVERSITY ANKARA February 2008 I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Oktay Özel Supervisor I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Halil Đnalcık Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Yaşar Ocak Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. …………………….. Assist. Prof. Evgeni Radushev Examining Committee Member I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. -

| | | | | | Naslefardanews Naslfarda

واد اتاد ور هان صبا با م ﺟﻨ ﺳﺎ ﺑﺪﺑﯿﻨﻰ ﺮ ﻪ ﺑﺎ و ﺑﺎ ﮔﺖ ﻣﺸ ﻣﯿﺪان اﻣﺎ ﻠ ﻰ ﺗﺎ اواﯾ ﺳﺎل آﯾﻨﺪ ﯿﺰ را ﻧﺎﺑﻮد ﮐﺮد ﺗﺎﺷﺎﮔﺮى ﮐﻪ ﯾﺎر ﻮاﺪ ﺷﺪ دﯾﮕﺮ ﺗﺤﻤﻞ ﺑﺪﮔﻤﺎﻧﻰ ﻫﺎ و ﺳــﻮءﻇﻦ او ﻣﻨﻄﻘﻪ 3 ﺷــﻬﺮدارى اﺻﻔﻬﺎن ﯾﮑﻰ از را ﻧﺪارم و اﺻﻼ ﻓﮑﺮ ﻣﻰ ﮐﻨﻢ ﺑﺎ ﮐﺴﯽ ﮐﻪ دوازد ﻧﯿﺖ ﺳﻪ ﻣﻨﻄ ﻘﻪ ﺑﺎ ﺑﯿﺸﺘﺮﯾﻦ ﺑﺎﻓﺖ ﺗﺎرﯾﺨﻰ، ﺳﻮء ﻇﻦ داﺷﺘﻪ ﺑﺎﺷﺪ، ﻧﻤﻰ ﺷﻮد زﻧﺪﮔﯽ ﺷــﻬﺮآورد ﻓﻮﺗﺒﺎل اﺻﻔﻬﺎن در ﺣﺎﻟﻰ ﺑﺎ رﺳﺎﻧ ﻪﺎ ﻣﺎﺋ ﺗﻰ ﺑﺎﻓﺖ ﻓﺮﺳﻮده، ﮔﻠﻮﮔ ﺎهﻫﺎ و ﭘﺎرﮐﯿﻨﮓ ﻫﺎ ﮐﺮد؛ ﭼﻨﺎن ﻣﻬﺮ او از دﻟﻢ رﻓﺘﻪ اﺳﺖ ﮐﻪ ﺎد ﻣﺎﻟﻰ ﺮ ﻟﻨﮕﺎن ﺑﺮﺗﺮى ﺳــﭙﺎﻫﺎن ﺑﻪ ﭘﺎﯾﺎن رﺳﯿﺪ ﮐﻪ ﺑﻌﺪ در اﺻﻔﻬﺎن اﺳﺖ و ﻧﯿﺰ ﻣﺤﻞ داد و ﺳﺘﺪ در آﻣﻮزش و ﭘﺮورش را ﺑﻪ ﺣﺎﻟﺖ ﺗﻨﻔﺮ رﺳﯿﺪه ام ،ﭼﻮن ﻣﻦ ﻫﯿﭻ اﺎد در ﺷﻬﺮ از 11 ﺳﺎل ﺑﺎز ﻫﻢ اﺳﺘﺎدﯾﻮم ﻧﻘ ﺶﺟﻬﺎن ﺗﺠﺎرى ﺑﺮاى 350 اﻟﻰ 400 ﻫﺰار ﻧﻔﺮ در راﺑﻄﻪاى ﺑﺎ ﻣﺮد دﯾﮕﺮى... 14 15 ﻣﯿﺰﺑﺎن رﻗﺎﺑﺖ دو ﺗﯿﻢ اﺻﻔﻬﺎﻧﻰ... 18 ﺮاﻣﻮش ﮐﺮد اﻧﺪ 14 ﻃﻰ روز اﺳﺖ... 16 ﭼﻬﺎرﺷﻨﺒﻪ| 18 اﺳﻔﻨﺪ 1395| 8 ﻣﺎرس 2017 | 9 ﺟﻤﺎدى اﻟﺜﺎﻧﻰ 1438 | ﺳﺎل ﺑﯿﺴﺖ و ﺷﺸﻢ| ﺷﻤﺎره 5356| ﺻﻔﺤﻪ WWW. NASLEFARDA.NET naslefardanews naslfarda 30007232 13 ﯾﺎاﺷﺖ ی ﺮ روزﻣﺎن ﻧﻮروز عی مهی در اصفهان ف ﭘﯿﺸﻨﻬﺎد اﻣﺮوز اﻣﯿﺮﺣﺴﯿﻦ ﭼﯿ ﺖﺳﺎززاده دم دﻣــﺎى ﻋﯿﺪ ﻧﻮروز ﮐﻪ ﻣﯿﺸــﻪ ﻋﺎم و ﺧﺎ ﯾﺎدﺷﻮن ﻣﯿﺎد ﺑﻪ ﺗﯿﯿﺮ و ﺗﺤﻮل دﺳﺖ ﺑﺰﻧﻦ؛ ﺣﺎﻻ از ﻣﺪﯾﺮﯾﺖ ﯾﮏ ﻓﻌﺎﻟﯿﺖ اﻗﺘﺼﺎدى ﺑﺎ اﺷــﮑﺎﻟﻰ ﻫﻤﭽﻮن ﻧﻮ ﻧﻮار ﮐــﺮدن ﻣﺤﺼﻮﻻت و ﺧﺪﻣﺎت اراﺋﻪ ﺷــﺪه و رﺳــﯿﺪﮔﻰ ﺑﻪ اﻣﻮر ﻣﺸﺘﺮﯾﺎن و ﯿﻠﺮ ﯾﻨ ﯾﻨﻰ دﮐﻮرﻫﺎى ﺟﺪﯾﺪﺗــﺮ و... ﮔﺮﻓﺘﻪ ﺗــﺎ ﻣﺪﯾﺮان و ﺧﺎدﻣﯿﻦ ﻣﺮدم ﮐﻪ ﺑﻪ ﯾﺎد رﺳــﯿﺪﮔﻰ ﺑﻪ ﻇﻮاﻫﺮ ﺷــﻬﺮى و آﻣﺎرى ﻣﻰاﻓﺘﻦ. -

ACM/ICPC 2016 - Tehran Site

ACM/ICPC 2016 - Tehran Site ID Institution Team Name 1 Urmia University Promotion 2 Islamic Azad University of Mashhad Ashkan Esfand Mere : '( 3 Ferdowsi University of Mashhad O__o 4 Sharif University of Technology mruxim 5 Semnan University grand master 6000 6 University of Isfahan smarties 7 Isfahan University of Technology TiZi Remembers 8 Sadjad University of Technology Why Do We Fall? 9 Kharazmi University Golabi 10 University of Tabriz Immortal Euler 11 Khaje Nasir Toosi University of Technology MSA 12 Tehran Technical College of Shariaty Shariaty 13 Shahab Danesh University bradders 14 Shahid Beheshti University Dog nine 15 Ferdowsi University of Mashhad Gharch Sokhari 16 Fasa University Sharp 17 Sheikhbahaee Universtity Ooo... 18 Isfahan University of Technology Team 47 19 University of Sistan and Baluchestan Makoran-USB 20 University of Tehran The Last One ? 21 Shahid Bahonar University of Kerman kerms 22 Shiraz University Sleepies :-Z 23 Sharif University of Technology KMJ Fans 24 Birjand University DeadLock 25 Isfahan University of Technology TRIO 26 University of Tehran NesheTeam 27 Shiraz University AYA? 28 Karaj Sama University Pioneer Sama 29 Somayeh Najaf Abad Technical College Team94 30 Payame Noor University of Mashhad Hamure Belad Nistom 31 Shiraz University AZINAA 32 Shahid Beheshti University Disqualified 33 Pasargad University of Shiraz The_Last_ACM 34 Gonbad Kavoos University ProMinu 35 Shahid Beheshti University uniVerse 36 Urmia University B.I.Z. 37 Isfahan University of Technology Iutbax 38 Sharif University -

Jnasci-2015-1195-1202

Journal of Novel Applied Sciences Available online at www.jnasci.org ©2015 JNAS Journal-2015-4-11/1195-1202 ISSN 2322-5149 ©2015 JNAS Relationships between Timurid Empire and Qara Qoyunlu & Aq Qoyunlu Turkmens Jamshid Norouzi1 and Wirya Azizi2* 1- Assistant Professor of History Department of Payame Noor University 2- M.A of Iran’s Islamic Era History of Payame Noor University Corresponding author: Wirya Azizi ABSTRACT: Following Abu Saeed Ilkhan’s death (from Mongol Empire), for half a century, Iranian lands were reigned by local rules. Finally, lately in the 8th century, Amir Timur thrived from Transoxiana in northeastern Iran, and gradually made obedient Iran and surrounding countries. However, in the Northwest of Iran, Turkmen tribes reigned but during the Timurid raids they had returned to obedience, and just as withdrawal of the Timurid troops, they were quickly back their former power. These clans and tribes sometimes were troublesome to the Ottoman Empires and Mamluk Sultanate of Egypt. Due to the remoteness of these regions of Timurid Capital and, more importantly, lack of permanent government administrations and organizations of the Timurid capital, following Amir Timur’s death, because of dynastic struggles among his Sons and Grandsons, the Turkmens under these conditions were increasing their power and then they had challenged the Timurid princes. The most important goals of this study has focused on investigation of their relationships and struggles. How and why Timurid Empire has begun to combat against Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu Turkmens; what were the reasons for the failure of the Timurid deal with them, these are the questions that we try to find the answers in our study. -

See the Document

IN THE NAME OF GOD IRAN NAMA RAILWAY TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN List of Content Preamble ....................................................................... 6 History ............................................................................. 7 Tehran Station ................................................................ 8 Tehran - Mashhad Route .............................................. 12 IRAN NRAILWAYAMA TOURISM GUIDE OF IRAN Tehran - Jolfa Route ..................................................... 32 Collection and Edition: Public Relations (RAI) Tourism Content Collection: Abdollah Abbaszadeh Design and Graphics: Reza Hozzar Moghaddam Photos: Siamak Iman Pour, Benyamin Tehran - Bandarabbas Route 48 Khodadadi, Hatef Homaei, Saeed Mahmoodi Aznaveh, javad Najaf ...................................... Alizadeh, Caspian Makak, Ocean Zakarian, Davood Vakilzadeh, Arash Simaei, Abbas Jafari, Mohammadreza Baharnaz, Homayoun Amir yeganeh, Kianush Jafari Producer: Public Relations (RAI) Tehran - Goragn Route 64 Translation: Seyed Ebrahim Fazli Zenooz - ................................................ International Affairs Bureau (RAI) Address: Public Relations, Central Building of Railways, Africa Blvd., Argentina Sq., Tehran- Iran. www.rai.ir Tehran - Shiraz Route................................................... 80 First Edition January 2016 All rights reserved. Tehran - Khorramshahr Route .................................... 96 Tehran - Kerman Route .............................................114 Islamic Republic of Iran The Railways -

Somayeh Vandghanooni, Medical Nanotechnology (Doctor of Philosophy) H-Index: 10 RG Score: 20.17 Research Items: 18 Citation: 350

Tabriz University of Medical [email protected] Sciences Phone: +98 41 33347054 University Street, Tabriz, Iran Fax: +98 41 33373919 https://orcid.org/0000-0003- 3400-4109 Scopus Author ID: 36955821200 Researcher ID: S-6166-2018 Google scholar Somayeh Vandghanooni, Medical Nanotechnology (Doctor of Philosophy) H-Index: 10 RG Score: 20.17 Research items: 18 Citation: 350 Education ........................................................................................................................................ 2 Thesis ............................................................................................................................................... 2 Employments ................................................................................................................................. 3 Grants .............................................................................................................................................. 3 Journal publications ...................................................................................................................... 4 Selected Conference Proceedings ................................................................................................ 6 Workshops ...................................................................................................................................... 6 Awards ............................................................................................................................................ 6 Gene registration