Revue D'etudes Tibétaines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mt. Kailash Pilgrimage Kora Grand Tour

MT. KAILASH PILGRIMAGE KORA GRAND TOUR Tashi delek! Tibetan Guide Travel Tours is a small travel agency based in Lhasa. We always work hard and take responsible for our clients by using local services as much as possible. Of course we use Tibetan drivers and tour guides. Who are experienced, have rich knowledge about Tibetan culture and also excellent attitude. We are confident that you would not be disappointed if you choose our services letting us show you our mother land. Proposed itinerary Day 1: Lhasa arrival [3650m] Upon arrival in Lhasa you will be welcomed by your English-speaking Tibetan Guide and Tibetan Driver who will bring you to your hotel. Acclimatization to high altitude: please, drink lots of water and take plenty of rest in order to minimize altitude sickness. Overnight at Shambhala Palace or House of Shambhala Hotel, which are a Tibetan style hotel located in Lhasa city center (Barkhor) Day 2: Lhasa sightseeing We begin visiting Ramoche Temple, built in honor of the image of Jowo Rinpoche that Chinese princess Wencheng brought by marrying Songtsen Gampo, the first king of Buddhist doctrine and who unified the Tibetan empire in the 7th century. Thereafter, we continue with Jokhang Temple, the most sacred monastery in Tibet. It was also founded in the 7th century by Songtsen Gampo. Later you can explore the surrounding Barkhor old quarter and spend time walking around Jokhang Temple following pilgrims from all over the Tibetan plateau. In the afternoon we go to Sera Monastery, one of three great universities of Gelugpa Sect. We will attend the debating session of the monks. -

On Bhutanese and Tibetan Dzongs **

ON BHUTANESE AND TIBETAN DZONGS ** Ingun Bruskeland Amundsen** “Seen from without, it´s a rocky escarpment! Seen from within, it´s all gold and treasure!”1 There used to be impressive dzong complexes in Tibet and areas of the Himalayas with Tibetan influence. Today most of them are lost or in ruins, a few are restored as museums, and it is only in Bhutan that we find the dzongs still alive today as administration centers and monasteries. This paper reviews some of what is known about the historical developments of the dzong type of buildings in Tibet and Bhutan, and I shall thus discuss towers, khars (mkhar) and dzongs (rdzong). The first two are included in this context as they are important in the broad picture of understanding the historical background and typological developments of the later dzongs. The etymological background for the term dzong is also to be elaborated. Backdrop What we call dzongs today have a long history of development through centuries of varying religious and socio-economic conditions. Bhutanese and Tibetan histories describe periods verging on civil and religious war while others were more peaceful. The living conditions were tough, even in peaceful times. Whatever wealth one possessed had to be very well protected, whether one was a layman or a lama, since warfare and strife appear to have been endemic. Security measures * Paper presented at the workshop "The Lhasa valley: History, Conservation and Modernisation of Tibetan Architecture" at CNRS in Paris Nov. 1997, and submitted for publication in 1999. ** Ingun B. Amundsen, architect MNAL, lived and worked in Bhutan from 1987 until 1998. -

Diversity and Co-Occurrence Patterns of Microbial Communities in the Fertilized Eggs of Thitarodes Insect, the Implication on the Occurrence of Chinese Cordyceps

Diversity and Co-Occurrence Patterns of microbial Communities in the Fertilized Eggs of Thitarodes Insect, the Implication on the Occurrence of Chinese cordyceps Lian-Xian Guo Guangdong Medical University Xiao-Shan Liu Guangdong Medical University Zhan-Hua Mai Guangdong Medical University Yue-Hui Hong Guangdong Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine Qi-Jiong Zhu Guangdong Medical University Xu-Ming Guo Guangdong Medical University Huan-Wen Tang ( [email protected] ) Guangdong Medical University Research article Keywords: Bacterial, Fungal, Fertilized Eggs, Thitarodes, Chinese cordyceps, Wolbachia Posted Date: April 28th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-24686/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/20 Abstract Background The large-scale articial cultivation of Chinese cordyceps has not been widely implemented because the crucial factors triggering the occurrence of Chinese cordyceps have not been fully illuminated. Methods In this study, the bacterial and fungal structure of fertilized eggs in the host Thitarodes collected from 3 sampling sites with different occurrence rates of Chinese cordyceps (Sites A, B and C: high, low and null Chinese cordyceps, respectively) were analyzed by performing 16S RNA and ITS sequencing, respectively. And the intra-kingdom and inter-kingdom network were analyzed. Results For bacterial community, totally 4671 bacterial OTUs were obtained. α-diversity analysis revealed that the evenness of the eggs from site A was signicantly higher than that of sites B and C, and the dominance index of site A was signicantly lower than that of sites B and C ( P < 0.05). -

Vidulaku- Mrokkeda-Raga.Html Youtube Class: Audio MP3 Class

Vidhulaku Mrokkedha Ragam: Mayamalavagowlai {15th Melakartha Ragam} https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayamalavagowla ARO: S R1 G3 M1 P D1 N3 S || AVA: A N3 D1 P M1 G3 R1 S || Talam: Adi Composer: Thyagaraja Version: M.S. Subbulakshmi (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=llsETzsGWzU ) Lyrics Courtesy: www.karnatik.com (Rani) and Lakshman Ragde http://www.geocities.com/promiserani2/c2933.html Meaning Courtesy: https://thyagaraja-vaibhavam.blogspot.com/2007/03/thyagaraja-kriti-vidulaku- mrokkeda-raga.html Youtube Class: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hWszTbKSkm0 Audio MP3 Class: http://www.shivkumar.org/music/vidulaku-class.mp3 Pallavi: vidulaku mrokkEda sangIta kO Anupallavi: mudamuna shankara krta sAma nigama vidulaku nAdAtmaka sapta svara Charanam: kamalA gaurI vAgIshvari vidhi garuDa dhvaja shiva nAradulu amarEsha bharata kashyapa caNDIsha AnjanEya guha gajamukhulu su-mrkaNDuja kumbhaja tumburu vara sOmEshvara shArnga dEva nandi pramukhulaku tyAgarAja vandyulaku brahmAnanda sudhAmbudhi marma Meaning Courtesy: https://thyagaraja-vaibhavam.blogspot.com/2007/03/thyagaraja-kriti-vidulaku- mrokkeda-raga.html Pallavi: Sahityam: vidulaku mrokkEda sangIta kO Meaning: I salute (mrokkeda) the maestros (kOvidulaku) of music (sangIta). Sahityam: mudamuna shankara krta sAma nigama vidulaku nAdAtmaka sapta svara Meaning: I joyously (mudamuna) salute - the masters (vidulaku) of sAma vEda (nigama) created (kRta) by Lord Sankara and the maestros (vidulaku) of sapta svara – nAda embodied (Atmaka) (nAdAtmaka). Sahityam:kamalA gaurI vAgIshvari vidhi garuDa dhvaja -

Cordyceps Medicinal Fungus: Harvest and Use in Tibet

HerbalGram 83 • August – October 2009 83 • August HerbalGram Kew’s 250th Anniversary • Reviving Graeco-Arabic Medicine • St. John’s Wort and Birth Control The Journal of the American Botanical Council Number 83 | August – October 2009 Kew’s 250th Anniversary • Reviving Graeco-Arabic Medicine • Lemongrass for Oral Thrush • Hibiscus for Blood Pressure • St. John’s Wort and BirthWort Control • St. John’s Blood Pressure • HibiscusThrush for Oral for 250th Anniversary Medicine • Reviving Graeco-Arabic • Lemongrass Kew’s US/CAN $6.95 Cordyceps Medicinal Fungus: www.herbalgram.org Harvest and Use in Tibet www.herbalgram.org www.herbalgram.org 2009 HerbalGram 83 | 1 STILL HERBAL AFTER ALL THESE YEARS Celebrating 30 Years of Supporting America’s Health The year 2009 marks Herb Pharm’s 30th anniversary as a leading producer and distributor of therapeutic herbal extracts. During this time we have continually emphasized the importance of using the best quality certified organically cultivated and sustainably-wildcrafted herbs to produce our herbal healthcare products. This is why we created the “Pharm Farm” – our certified organic herb farm, and the “Plant Plant” – our modern, FDA-audited production facility. It is here that we integrate the centuries-old, time-proven knowledge and wisdom of traditional herbal medicine with the herbal sciences and technology of the 21st Century. Equally important, Herb Pharm has taken a leadership role in social and environmental responsibility through projects like our use of the Blue Sky renewable energy program, our farm’s streams and Supporting America’s Health creeks conservation program, and the Botanical Sanctuary program Since 1979 whereby we research and develop practical methods for the conser- vation and organic cultivation of endangered wild medicinal herbs. -

He Noble Path

HE NOBLE PATH THE NOBLE PATH TREASURES OF BUDDHISM AT THE CHESTER BEATTY LIBRARY AND GALLERY OF ORIENTAL ART DUBLIN, IRELAND MARCH 1991 Published by the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. 1991 ISBN:0 9517380 0 3 Printed in Ireland by The Criterion Press Photographic Credits: Pieterse Davison International Ltd: Cat. Nos. 5, 9, 12, 16, 17, 18, 21, 22, 25, 26, 27, 29, 32, 36, 37, 43 (cover), 46, 50, 54, 58, 59, 63, 64, 65, 70, 72, 75, 78. Courtesy of the National Museum of Ireland: Cat. Nos. 1, 2 (cover), 52, 81, 83. Front cover reproduced by kind permission of the National Museum of Ireland © Back cover reproduced by courtesy of the Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library © Copyright © Trustees of the Chester Beatty Library and Gallery of Oriental Art, Dublin. Chester Beatty Library 10002780 10002780 Contents Introduction Page 1-3 Buddhism in Burma and Thailand Essay 4 Burma Cat. Nos. 1-14 Cases A B C D 5 - 11 Thailand Cat. Nos. 15 - 18 Case E 12 - 14 Buddhism in China Essay 15 China Cat. Nos. 19-27 Cases F G H I 16 - 19 Buddhism in Tibet and Mongolia Essay 20 Tibet Cat. Nos. 28 - 57 Cases J K L 21 - 30 Mongolia Cat. No. 58 Case L 30 Buddhism in Japan Essay 31 Japan Cat. Nos. 59 - 79 Cases M N O P Q 32 - 39 India Cat. Nos. 80 - 83 Case R 40 Glossary 41 - 48 Suggestions for Further Reading 49 Map 50 ■ '-ie?;- ' . , ^ . h ':'m' ':4^n *r-,:«.ria-,'.:: M.,, i Acknowledgments Much credit for this exhibition goes to the Far Eastern and Japanese Curators at the Chester Beatty Library, who selected the exhibits and collaborated in the design and mounting of the exhibition, and who wrote the text and entries for the catalogue. -

Durchs Ferne Westtibet Mit Lokaler Englischsprechender Reiseleitung 1 20 X Keine 5400 M Von Lhasa Zum Heiligen Berg Kailash Und Weiter Nach Kashgar

Durchs ferne Westtibet mit lokaler englischsprechender Reiseleitung 1 20 x keine 5400 m Von Lhasa zum heiligen Berg Kailash und weiter nach Kashgar 8. – 29. August 2021 Ideale Reisezeit Jan Feb Mär Apr Mai Jun Jul Aug Sep Okt Nov Dez Hinweis: Der Sommer (Juli und August) ist die Hauptreisezeit für die chinesischen Touristen. Es hat aber in der Regel mehr Niederschlag als im Frühling oder Herbst (vergleichbar mit einem durchschnittlichen Schweizer Sommer) und die Bergsicht kann eher eingeschränkt sein. __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Höhepunkte • Auf den Spuren von Sven Hedin durch den Transhimalaya • Potala-Palast in Lhasa • Besuch der Kailash-Region ohne Trekking • Tholing und Tsaparang im ehemaligen Königreich Guge • Selten gefahrene Strecke bis nach Kashgar __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Dies ist die Traumreise für all diejenigen, welche sich eine Kombination von Tibet, Buddhismus und Seidenstrasse wünschen. In Lhasa besuchen wir den mächtigen Potala-Palast und den Jokhang, den heiligsten Tempel Tibets. In Gyantse staunen wir über die eigenartige Architektur des grossen Kumbum-Chörten und während unserer Fahrt zum Kailash geniessen wir das einmalig schöne Panorama der Himalaya-Kette. Nach einigen Tagen erreichen wir den stahlblauen Manasarovar-See, welcher auf einer Höhe von 4500 Metern liegt. Wir umrunden diesen See und geniessen die verschiedenen Anblicke des heiligen Berges Kailash. Anschliessend reisen wir weiter nach Westen in nur wenig besuchte Regionen. Im ehemaligen Königreich Guge stehen einige der ältesten Zeugen der buddhistischen Kunst. Unsere spannende Weiterfahrt bringt uns durch das Kunlun- Gebirge, über das Hochplateau von Aksai Chin und weiter bis zum Karakorum-Gebirge. Wir durchqueren dabei phantastische und archaische Berglandschaften, bis wir schlussendlich die alte Karawanenstadt Kashgar erreichen. -

Vasubandhu's) Commentary on His "Twenty Stanzas" with Appended Glossary of Technical Terms

AN INTRODUCTION AND TRANSLATION OF VINITADEVA'S EXPLANATION OF THE FIRST TEN VERSES OF (VASUBANDHU'S) COMMENTARY ON HIS "TWENTY STANZAS" WITH APPENDED GLOSSARY OF TECHNICAL TERMS Gregory Alexander Hillis Palo Alto, California B.A., University of California, Santa Cruz, 1979 A Thesis Presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Religious Studies University of Virginia May, 1993 ABSTRACT In this thesis I argue that Vasubandhu categorically rejects the position that objects exist external to the mind. To support this interpretation, I engage in a close reading of Vasubandhu's Twenty Stanzas (Vif!lsatika, nyi shu pa), his autocommentary (vif!lsatika- vrtti, nyi shu pa'i 'grel pa), and Vinrtadeva's sub-commentary (prakaraiJa-vif!liaka-f'ika, rab tu byed pa nyi shu pa' i 'grel bshad). I endeavor to show how unambiguous statements in Vasubandhu's root text and autocommentary refuting the existence of external objects are further supported by Vinitadeva's explanantion. I examine two major streams of recent non-traditional scholarship on this topic, one that interprets Vasubandhu to be a realist, and one that interprets him to be an idealist. I argue strenuously against the former position, citing what I consider to be the questionable methodology of reading the thought of later thinkers such as Dignaga and Dharmak:Irti into the works of Vasubandhu, and argue in favor of the latter position with the stipulation that Vasubandhu does accept a plurality of separate minds, and he does not assert the existence of an Absolute Mind. -

7 Days Tibet Cultural Tour with Gyantse Fort and Shigatse

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 7 days Tibet cultural tour with Gyantse Fort and Shigatse https://windhorsetour.com/lhasa-tour/lhasa-yamdrok-lake-gyantse-shigatse-tour Lhasa Gyantse Shigatse Lhasa Get up close and explore Tibet's soul! Learn about the reach culture and history by going straight to Tibet's heart. Stop and visit local families, in their traditional homes as you travel from Lhasa to Shigatse and beyond. Type Private Duration 7 days Theme Winter getaways Trip code TWT-TCH-02 Price From £ 493 per person Itinerary Day 01 : Arrival at Lhasa (3600m) At your arrival your Tibetan guide and driver will pick you up and transfer to the hotel in Lhasa, it is only 68km and two hours from the airport, from 15km which take 20 minutes. Take rest to acclimatize and alleviate jetlag. Overnight at Lhasa. Day 02 : Lhasa city sightseeing (3600m) (B) After breakfast, visit Jokhang temple, the most sacred shrine in Tibet which was built in the 7th century and located at the heart of old town in Lhasa, the circuit around it called Barkhor street, which is a good place to purchase souvenirs. Potala Palace is the worldwide known cardinal landmark of Tibet. The massive structure itself contains a small world within it. Mostly it is renowned as residence of the Dalai Lama lineages (Avalokiteshvara). Both of them are the focal points of pilgrims from the entire Tibetan world, multitudinous pilgrims are circumambulating and prostrating in their strong faith. Overnight at Lhasa. Day 03 : Lhasa City sightseeing, visit Drepung monastery and Sera monastery (3600m)(B) Today you will be arranged to visit Drepung and Sera monasteries. -

Buddhist Backgrounds of the Burmese Revolution Buddhist Backgrounds Ofthe Burmese Revolution

BUDDHIST BACKGROUNDS OF THE BURMESE REVOLUTION BUDDHIST BACKGROUNDS OFTHE BURMESE REVOLUTION by E. SARKISYANZ PH.D. apl. Professor Freiburg University PREFACE BY DR. PAUL MUS Professor at the College de France and Yale University • Springer-Science+Business Media, B.Y. I965 Dedicated to the memory 01 my unlorgettable teacher ARNOLD BERGSTRAESSER ISBN 978-94-017-5830-7 ISBN 978-94-017-6283-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-017-6283-0 Copyright I965 by Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht All rights reserved, including the right to translate or to reproduce this book or parts thereof in any form Originally published by Martinus Nijhoff in 1965. Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover 1st edition 1965 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface by PAUL Mus. VII Foreword ..... XXIII Abbreviations . XXVII I. The Buddhist tradition of Burma's history . I 11. Buddhist traditions about a perfect society, its decline and the origin of the state . .. 10 III. Republican institutions in pre-Buddhist India and in the Buddhist order. .. 17 IV. The Buddhist welfare state of Ashoka. .. 26 v. Survival of Ashokan social and political traditions in Theravada kingship . .. 33 VI. On the problem of social ethics of Theravada Buddhism 37 VII. Emergence of the Bodhisattva ideal of kingship in Theravada Buddhism . .. 43 VIII. Pre-Buddhist fertility elements of the charisma of Burmese kingship . .. 49 IX. Economic implications of the Buddhist ideal of kingship 54 x. The Bodhisattva ideal of Burmese kingship . .. 59 XI. Kamma and Buddhist merit-causality as rationale for medieval Burma's social order . .. 68 XII. Buddhist ethics against the pragmatism of power under the Burmese kings. -

Under Memberships

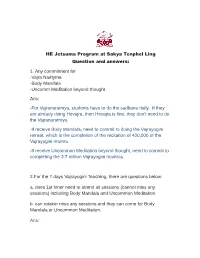

HE Jetsuma Program at Sakya Tenphel Ling Question and answers: 1. Any commitment for -Vajra Nairtyma -Body Mandala -Uncomm Meditation beyond thought Ans: -For Vajranaratmya, students have to do the sadhana daily. If they are already doing Hevajra, then Hevajra is fine, they don’t need to do the Vajranaratmya. -If receive Body Mandala, need to commit to doing the Vajrayogini retreat, which is the completion of the recitation of 400,000 of the Vajrayogini mantra. -If receive Uncommon Meditation beyond thought, need to commit to completing the 3.7 million Vajrayogini mantras. 2.For the 7 days Vajrayogini Teaching, there are questions below: a. does 1st timer need to attend all sessions (cannot miss any sessions) including Body Mandala and Uncommon Meditation. b. can retaker miss any sessions.and they can come for Body Mandala or Uncommon Meditation. Ans: a. Students who want to receive the proper transmission should attend all the sessions. However, if they don’t wish to receive the commitments of retreat and mantra accumulation (3.7 million), as is required if receive the body mandala and uncommon meditation beyond thought, they can skip those relevant sessions. b. For old timers who received the entire set before, it is their choice. However, Jetsun Kushok thinks it is beneficial to receive the teachings in its entirety without selectively choosing and skipping. 3.a For those new ones who.has taken 2 days Vajra Nairatyma empowerment, can they continue to take Vajrayogini Chin Lab and then go to the 7 days teaching? b. For those who.have taken 2 days Hevajra cause empowerment, they can come for Vajra Nairatyma empowerment and no need be one of the 25 new takers. -

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Writings & Speeches Vol. 4

Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar (14th April 1891 - 6th December 1956) BLANK DR. BABASAHEB AMBEDKAR WRITINGS AND SPEECHES VOL. 4 Compiled by VASANT MOON Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar : Writings and Speeches Vol. 4 First Edition by Education Department, Govt. of Maharashtra : October 1987 Re-printed by Dr. Ambedkar Foundation : January, 2014 ISBN (Set) : 978-93-5109-064-9 Courtesy : Monogram used on the Cover page is taken from Babasaheb Dr. Ambedkar’s Letterhead. © Secretary Education Department Government of Maharashtra Price : One Set of 1 to 17 Volumes (20 Books) : Rs. 3000/- Publisher: Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Ministry of Social Justice & Empowerment, Govt. of India 15, Janpath, New Delhi - 110 001 Phone : 011-23357625, 23320571, 23320589 Fax : 011-23320582 Website : www.ambedkarfoundation.nic.in The Education Department Government of Maharashtra, Bombay-400032 for Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Source Material Publication Committee Printer M/s. Tan Prints India Pvt. Ltd., N. H. 10, Village-Rohad, Distt. Jhajjar, Haryana Minister for Social Justice and Empowerment & Chairperson, Dr. Ambedkar Foundation Kumari Selja MESSAGE Babasaheb Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the Chief Architect of Indian Constitution was a scholar par excellence, a philosopher, a visionary, an emancipator and a true nationalist. He led a number of social movements to secure human rights to the oppressed and depressed sections of the society. He stands as a symbol of struggle for social justice. The Government of Maharashtra has done a highly commendable work of publication of volumes of unpublished works of Dr. Ambedkar, which have brought out his ideology and philosophy before the Nation and the world. In pursuance of the recommendations of the Centenary Celebrations Committee of Dr.