7.Phase Diagram 7.1. Definition and Basic Concept Single And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lecture Notes: BCS Theory of Superconductivity

Lecture Notes: BCS theory of superconductivity Prof. Rafael M. Fernandes Here we will discuss a new ground state of the interacting electron gas: the superconducting state. In this macroscopic quantum state, the electrons form coherent bound states called Cooper pairs, which dramatically change the macroscopic properties of the system, giving rise to perfect conductivity and perfect diamagnetism. We will mostly focus on conventional superconductors, where the Cooper pairs originate from a small attractive electron-electron interaction mediated by phonons. However, in the so- called unconventional superconductors - a topic of intense research in current solid state physics - the pairing can originate even from purely repulsive interactions. 1 Phenomenology Superconductivity was discovered by Kamerlingh-Onnes in 1911, when he was studying the transport properties of Hg (mercury) at low temperatures. He found that below the liquifying temperature of helium, at around 4:2 K, the resistivity of Hg would suddenly drop to zero. Although at the time there was not a well established model for the low-temperature behavior of transport in metals, the result was quite surprising, as the expectations were that the resistivity would either go to zero or diverge at T = 0, but not vanish at a finite temperature. In a metal the resistivity at low temperatures has a constant contribution from impurity scattering, a T 2 contribution from electron-electron scattering, and a T 5 contribution from phonon scattering. Thus, the vanishing of the resistivity at low temperatures is a clear indication of a new ground state. Another key property of the superconductor was discovered in 1933 by Meissner. -

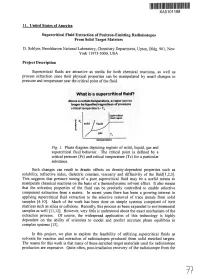

Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Positron-Emitting Radioisotopes from Solid Target Matrices

XA0101188 11. United States of America Supercritical Fluid Extraction of Positron-Emitting Radioisotopes From Solid Target Matrices D. Schlyer, Brookhaven National Laboratory, Chemistry Department, Upton, Bldg. 901, New York 11973-5000, USA Project Description Supercritical fluids are attractive as media for both chemical reactions, as well as process extraction since their physical properties can be manipulated by small changes in pressure and temperature near the critical point of the fluid. What is a supercritical fluid? Above a certain temperature, a vapor can no longer be liquefied regardless of pressure critical temperature - Tc supercritical fluid r«gi on solid a u & temperature Fig. 1. Phase diagram depicting regions of solid, liquid, gas and supercritical fluid behavior. The critical point is defined by a critical pressure (Pc) and critical temperature (Tc) for a particular substance. Such changes can result in drastic effects on density-dependent properties such as solubility, refractive index, dielectric constant, viscosity and diffusivity of the fluid[l,2,3]. This suggests that pressure tuning of a pure supercritical fluid may be a useful means to manipulate chemical reactions on the basis of a thermodynamic solvent effect. It also means that the solvation properties of the fluid can be precisely controlled to enable selective component extraction from a matrix. In recent years there has been a growing interest in applying supercritical fluid extraction to the selective removal of trace metals from solid samples [4-10]. Much of the work has been done on simple systems comprised of inert matrices such as silica or cellulose. Recently, this process as been expanded to environmental samples as well [11,12]. -

Equation of State and Phase Transitions in the Nuclear

National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine Bogolyubov Institute for Theoretical Physics Has the rights of a manuscript Bugaev Kyrill Alekseevich UDC: 532.51; 533.77; 539.125/126; 544.586.6 Equation of State and Phase Transitions in the Nuclear and Hadronic Systems Speciality 01.04.02 - theoretical physics DISSERTATION to receive a scientific degree of the Doctor of Science in physics and mathematics arXiv:1012.3400v1 [nucl-th] 15 Dec 2010 Kiev - 2009 2 Abstract An investigation of strongly interacting matter equation of state remains one of the major tasks of modern high energy nuclear physics for almost a quarter of century. The present work is my doctor of science thesis which contains my contribution (42 works) to this field made between 1993 and 2008. Inhere I mainly discuss the common physical and mathematical features of several exactly solvable statistical models which describe the nuclear liquid-gas phase transition and the deconfinement phase transition. Luckily, in some cases it was possible to rigorously extend the solutions found in thermodynamic limit to finite volumes and to formulate the finite volume analogs of phases directly from the grand canonical partition. It turns out that finite volume (surface) of a system generates also the temporal constraints, i.e. the finite formation/decay time of possible states in this finite system. Among other results I would like to mention the calculation of upper and lower bounds for the surface entropy of physical clusters within the Hills and Dales model; evaluation of the second virial coefficient which accounts for the Lorentz contraction of the hard core repulsing potential between hadrons; inclusion of large width of heavy quark-gluon bags into statistical description. -

Lecture 5 Non-Aqueous Phase Liquid (NAPL) Fate and Transport

Lecture 5 Non-Aqueous Phase Liquid (NAPL) Fate and Transport Factors affecting NAPL movement Fluid properties: Porous medium: 9 Density Permeability 9 Interfacial tension Pore size 9 Residual saturation Structure Partitioning properties Solubility Ground water: Volatility and vapor density Water content 9 Velocity Partitioning processes NAPL can partition between four phases: NAPL Gas Solid (vapor) Aqueous solution Water to gas partitioning (volatilization) Aqueous ↔ gaseous Henry’s Law (for dilute solutions) 3 Dimensionless (CG, CW in moles/m ) C G = H′ CW Dimensional (P = partial pressure in atm) P = H CW Henry’s Law Constant H has dimensions: atm m3 / mol H’ is dimensionless H’ = H/RT R = gas constant = 8.20575 x 10-5 atm m3/mol °K T = temperature in °K NAPL to gas partitioning (volatilization) NAPL ↔ gaseous Raoult’s Law: CG = Xt (P°/RT) Xt = mole fraction of compound in NAPL [-] P° = pure compound vapor pressure [atm] R = universal gas constant [m3-atm/mole/°K] T = temperature [°K] Volatility Vapor pressure P° is measure of volatility P° > 1.3 x 10-3 atm → compound is “volatile” 1.3 x 10-3 > P° > 1.3 x 10-13 atm → compound is “semi-volatile” Example: equilibrium with benzene P° = 76 mm Hg at 20°C = 0.1 atm R = 8.205 x 10-5 m3-atm/mol/°K T = 20°C (assumed) = 293°K Assume 100% benzene, mole fraction Xt = 1 3 CG = Xt P°/(RT) = 4.16 mol/m Molecular weight of benzene, C6H6 = 78 g/mol 3 3 CG = 4.16 mol/m × 78 g/mol = 324 g/m = 0.32 g/L 6 CG = 0.32 g/L x 24 L/mol / (78 g/mol) x 10 = 99,000 ppmv One mole of ideal gas = 22.4 L at STP (1 atm, 0 C), Corrected to 20 C: 293/273*22.4 = 24.0 L/mol Gas concentration in equilibrium with pure benzene NAPL Example: equilibrium with gasoline Gasoline is complex mixture – mole fraction is difficult to determine and varies Benzene = 1 to several percent (Cline et al., 1991) Based on analysis reported by Johnson et al. -

Introduction to Unconventional Superconductivity Manfred Sigrist

Introduction to Unconventional Superconductivity Manfred Sigrist Theoretische Physik, ETH-Hönggerberg, 8093 Zürich, Switzerland Abstract. This lecture gives a basic introduction into some aspects of the unconventionalsupercon- ductivity. First we analyze the conditions to realized unconventional superconductivity in strongly correlated electron systems. Then an introduction of the generalized BCS theory is given and sev- eral key properties of unconventional pairing states are discussed. The phenomenological treatment based on the Ginzburg-Landau formulations provides a view on unconventional superconductivity based on the conceptof symmetry breaking.Finally some aspects of two examples will be discussed: high-temperature superconductivity and spin-triplet superconductivity in Sr2RuO4. Keywords: Unconventional superconductivity, high-temperature superconductivity, Sr2RuO4 INTRODUCTION Superconductivity remains to be one of the most fascinating and intriguing phases of matter even nearly hundred years after its first observation. Owing to the breakthrough in 1957 by Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer we understand superconductivity as a conden- sate of electron pairs, so-called Cooper pairs, which form due to an attractive interaction among electrons. In the superconducting materials known until the mid-seventies this interaction is mediated by electron-phonon coupling which gises rise to Cooper pairs in the most symmetric form, i.e. vanishing relative orbital angular momentum and spin sin- glet configuration (nowadays called s-wave pairing). After the introduction of the BCS concept, also studies of alternative pairing forms started. Early on Anderson and Morel [1] as well as Balian and Werthamer [2] investigated superconducting phases which later would be identified as the A- and the B-phase of superfluid 3He [3]. In contrast to the s-wave superconductors the A- and B-phase are characterized by Cooper pairs with an- gular momentum 1 and spin-triplet configuration. -

Phase Diagrams a Phase Diagram Is Used to Show the Relationship Between Temperature, Pressure and State of Matter

Phase Diagrams A phase diagram is used to show the relationship between temperature, pressure and state of matter. Before moving ahead, let us review some vocabulary and particle diagrams. States of Matter Solid: rigid, has definite volume and definite shape Liquid: flows, has definite volume, but takes the shape of the container Gas: flows, no definite volume or shape, shape and volume are determined by container Plasma: atoms are separated into nuclei (neutrons and protons) and electrons, no definite volume or shape Changes of States of Matter Freezing start as a liquid, end as a solid, slowing particle motion, forming more intermolecular bonds Melting start as a solid, end as a liquid, increasing particle motion, break some intermolecular bonds Condensation start as a gas, end as a liquid, decreasing particle motion, form intermolecular bonds Evaporation/Boiling/Vaporization start as a liquid, end as a gas, increasing particle motion, break intermolecular bonds Sublimation Starts as a solid, ends as a gas, increases particle speed, breaks intermolecular bonds Deposition Starts as a gas, ends as a solid, decreases particle speed, forms intermolecular bonds http://phet.colorado.edu/en/simulation/states- of-matter The flat sections on the graph are the points where a phase change is occurring. Both states of matter are present at the same time. In the flat sections, heat is being removed by the formation of intermolecular bonds. The flat points are phase changes. The heat added to the system are being used to break intermolecular bonds. PHASE DIAGRAMS Phase diagrams are used to show when a specific substance will change its state of matter (alignment of particles and distance between particles). -

States of Matter

States of Matter A Museum of Science Traveling Program Description States of Matter is a 60- minute presentation about the characteristics of solids, liquids, gases, and the temperature- dependent transitions between them. It is designed to build on NGSS-based curricula. NGSS: Next Generation Science Standards Needs We bring all materials and equipment, including a video projector and screen. Access to 110- volt electricity is required. Space Requirements The program can be presented in assembly- suitable spaces like gyms, multipurpose rooms, cafeterias, and auditoriums. Goals: Changing State A major goal is to show that all substances will go through phase changes and that every substance has its own temperatures at which it changes state. Goals: Boiling Liquid nitrogen boils when exposed to room temperature. When used with every day objects, it can lead to unexpected results! Goals: Condensing Placing balloons in liquid nitrogen causes the gas inside to condense, shrinking the balloons before the eyes of the audience! Latex-free balloons are available for schools with allergic students. Goals: Freezing Nitrogen can also be used to flash-freeze a variety of liquids. Students are encouraged to predict the results, and may end up surprised! Goals: Behavior Changes When solids encounter liquid nitrogen, they can no longer change state, but their properties may have drastic—sometimes even shattering— changes. Finale Likewise, the properties of gas can change at extreme temperatures. At the end of the program, a blast of steam is superheated… Finale …incinerating a piece of paper! Additional Content In addition to these core goals, other concepts are taught with a variety of additional demonstrations. -

Superconductivity in Pictures

Superconductivity in pictures Alexey Bezryadin Department of Physics University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Superconductivity observation Electrical resistance of some metals drops to zero below a certain temperature which is called "critical temperature“ (H. K. O. 1911) How to observe superconductivity Heike Kamerling Onnes - Take Nb wire - Connect to a voltmeter and a current source - Put into helium Dewar - Measure electrical resistance R (Ohm) A Rs V Nb wire T (K) 10 300 Dewar with liquid Helium (4.2K) Meissner effect – the key signature of superconductivity Magnetic levitation Magnetic levitation train Fundamental property of superconductors: Little-Parks effect (’62) The basic idea: magnetic field induces non-zero vector-potential, which produces non- zero superfluid velocity, thus reducing the Tc. Proves physical reality of the vector- potential Discovery of the proximity Non-superconductor (normal metal, i.e., Ag) effect: A supercurrent can flow through a thin layers of a non- superconducting metals “sandwitched” between two superconducting metals. tin Superconductor (tin) Explanation of the supercurrent in SNS junctions --- Andreev reflection tin A.F. Andreev, 1964 Superconducting vortices carry magnetic field into the superconductor (type-II superconductivity) Amazing fact: unlike real tornadoes, superconducting vortices (also called Abrikosov vortices) are all exactly the same and carry one quantum of the Magnetic flux, h/(2e). By the way, the factor “2e”, not just “e”, proves that superconducting electrons move in pairs. -

8. Gas-Phase Kinetics

8. Gas-Phase Kinetics The unimolecular decomposition of gaseous di-tert-butyl peroxide is studied by monitoring the increase in the total pressure that results from the formation of three moles of gaseous products for each mole of reactant. The reaction is studied as a function of initial pressure, in the range 30-80 torr, and at two temperatures — ~150˚C and ~165˚C. General Reading 1. Oxtoby, Nachtrieb, and Freeman, Chemistry: Science of Change (2nd edit.); Sections 15.1-15.3 and 15.5-15.6. 2. Shoemaker, Garland, and Nibler, Experiments in Physical Chemistry (6th edit.); pp. 280-290 (Experiment 24); pp. 630-631 (manometers). [See also especially ref. 15 listed on p. 290.] 3. Levine, Physical Chemistry (4th edit.); Section 17.10 (unimolecular reaction theory). Theory Gas-phase decomposition reactions often exhibit first-order kinetics. Yet it is now understood that the mechanisms for these reactions are actually bimolecular in nature. The reaction is initiated by collisional activation (bimolecular) to an energy that is high enough to undergo decomposition, A + A ® A + A* k1 (1) where A* represents the activated molecule. The observed first-order behavior is a consequence of a competition between the reverse of this process (collisional deactivation), A* + A ® A + A k2 (2) and the decay of A* to products, A* ® products kA (3) When the rate of Process (2) is much greater than that of (3), the concentration of A* is maintained essentially at its equilibrium level. Then Process (3) becomes the rate-determining step, and the reaction exhibits first-order kinetics. This qualitative description can also be reached more quantitatively by employing the steady-state approximation, whereby the rates of change for reaction intermediates are set equal to zero. -

Experiment 4-Heat of Fusion and Melting Ice Experiment

Experiment 4-Heat of Fusion and Melting Ice Experiment In this lab, the heat of fusion for water will be determined by monitoring the temperature changes while a known mass of ice melts in a cup of water. The experimentally determined value for heat of fusion will be compared with the accepted standard value. We will also explore the following question regarding the rates of melting for ice cubes is posed: Will ice cubes melt faster in distilled water or in salt water? Part A-Heat of Fusion A phase change is a term physicists use for the conversion of matter from one of its forms (solid, liquid, gas) to another. Examples would be the melting of solid wax to a liquid, the evaporation of liquid water to water vapor, or condensation of a gas to a liquid. The melting of a solid to a liquid is called fusion. As a phase change occurs, say the evaporation of boiling water, the temperature of the material remains constant. Thus, a pot of boiling water on your stove remains at 100 °C until all of the water is gone. Even if the pot is over a big flame that is 900 °C, the water in the pot will only be 100 °C. A tray of water in your freezer will approach 0 °C and remain at that temperature until the water is frozen, no matter how cold the freezer is. In a phase change, heat energy is being absorbed or emitted without changing the temperature of the material. The amount of energy that is absorbed or emitted during a phase change obviously depends on the mass of the material undergoing the change. -

Two-Phase Gas/Liquid Pipe Flow

Two-Phase Gas/Liquid Pipe Flow Ron Darby PhD, PE Professor Emeritus, Chemical Engineering Texas A&M University Types of Two-Phase Flow »Solid-Gas »Solid-Liquid »Gas-Liquid »Liquid-Liquid Gas-Liquid Flow Regimes . Homogeneous . Highly Mixed . “Pseudo Single-Phase” . High Reynolds Number . Dispersed –Many Possibilities . Horizontal Pipe Flow . Vertical Pipe Flow Horizontal Dispersed Flow Regimes Vertical Pipe Flow Regimes Horizontal Pipe Flow Regime Map 1/ 2 G L AW 2 1/ 2 WLW LWL Vertical Pipe Flow Regime Map DEFINITIONS Mass Flow Rate m , Volume Flow Rate (Q) m mLGLLGG m Q Q Mass Flux (G): m m m GGG L G AAA LG Volume Flux (J): G GL GG JJJLG m L G QQ LGV A m Volume Fraction Gas: ε Vol. Fraction Liquid: 1-ε Phase Velocity: J J V,VL G LG1 Slip Ratio (S): Mass Fraction Gas (Quality x): V m S G x G VL mmGL Mass Flow Ratio Gas/Liquid: m x GGS m 1 - x 1 - LL Density of Two-Phase Mixture: m G 1 L where x ε x S 1 x ρGL / ρ is the volume fraction of gas in the mixture Holdup (Volume Fraction Liquid): S 1 x ρGL / ρ φ 1 ε x S 1 x ρGL / ρ Slip (S) . Occurs because the gas expands and speeds up relative to the liquid. It depends upon fluid properties and flow conditions. There are many “models” for slip (or holdup) in the literature. Hughmark (1962) slip correlation Either horizontal or vertical flow: 1 K 1 x / x ρ / ρ S GL K 1 x / x ρ / ρ GL where 19 K 1 0.12 / Z 0.95 1/ 6 1/ 8 1/ 4 Z NRe N Fr / 1 ε HOMOGENEOUS GAS-LIQUID PIPE FLOW Energy Balance (Eng’q Bernoulli Eqn) 2 f G 2 dx dz m G 2ν ρ g dP ρ DGL dL m dL m dL 2 dν 1 xG G dP where νGL ν G ν L 1 / ρ G 1 / ρ L For “frozen” flow (no phase change): dx 0 dL dν If xG 2 G 1 flow is choked. -

Lecture 8 Phases, Evaporation & Latent Heat

LECTURE 8 PHASES, EVAPORATION & LATENT HEAT Lecture Instructor: Kazumi Tolich Lecture 8 2 ¨ Reading chapter 17.4 to 17.5 ¤ Phase equilibrium ¤ Evaporation ¤ Latent heats n Latent heat of fusion n Latent heat of vaporization n Latent heat of sublimation Phase equilibrium & vapor-pressure curve 3 ¨ If a substance has two or more phases that coexist in a steady and stable fashion, the substance is in phase equilibrium. ¨ The pressure of the gas when equilibrium is reached is called equilibrium vapor pressure. ¨ A plot of the equilibrium vapor pressure versus temperature is called vapor-pressure curve. ¨ A liquid boils at the temperature at which its vapor pressure equals the external pressure. Phase diagram 4 ¨ A fusion curve indicates where the solid and liquid phases are in equilibrium. ¨ A sublimation curve indicates where the solid and gas phases are in equilibrium. ¨ A plot showing a vapor-pressure curve, a fusion curve, and a sublimation curve is called a phase diagram. ¨ The vapor-pressure curve comes to an end at the critical point. Beyond the critical point, there is no distinction between liquid and gas. ¨ At triple point, all three phases, solid, liquid, and gas, are in equilibrium. ¤ In water, the triple point occur at T = 273.16 K and P = 611.2 Pa. Quiz: 1 5 ¨ In most substance, as the pressure increases, the melting temperature of the substance also increases because a solid is denser than the corresponding liquid. But in water, ice is less dense than liquid water. Does the fusion curve of water have a positive or negative slope? A.