Irss 40 (2015) 103

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing)

Programme MONDAY 30 JUNE 10.00-11.00 Plenary: Dr Sally Mapstone “Myllar's and Chepman's Prints” (Strand: Early Printing) 11.00-11.30 Coffee 11.30-1.00 Session 1 A) Narrating the Nation: Historiography and Identity in Stewart Scotland (c.1440- 1540): a) „Dream and Vision in the Scotichronicon‟, Kylie Murray, Lincoln College, Oxford. b) „Imagined Histories: Memory and Nation in Hary‟s Wallace‟, Kate Ash, University of Manchester. c) „The Politics of Translation in Bellenden‟s Chronicle of Scotland‟, Ryoko Harikae, St Hilda‟s College, Oxford. B) Script to Print: a) „George Buchanan‟s De jure regni apud Scotos: from Script to Print…‟, Carine Ferradou, University of Aix-en-Provence. b) „To expone strange histories and termis wild‟: the glossing of Douglas‟s Eneados in manuscript and print‟, Jane Griffiths, University of Bristol. c) „Poetry of Alexander Craig of Rosecraig‟, Michael Spiller, University of Aberdeen. 1.00-2.00 Lunch 2.00-3.30 Session 2 A) Gavin Douglas: a) „„Throw owt the ile yclepit Albyon‟ and beyond: tradition and rewriting Gavin Douglas‟, Valentina Bricchi, b) „„The wild fury of Turnus, now lyis slayn‟: Chivalry and Alienation in Gavin Douglas‟ Eneados‟, Anna Caughey, Christ Church College, Oxford. c) „Rereading the „cleaned‟ „Aeneid‟: Gavin Douglas‟ „dirty‟ „Eneados‟, Tom Rutledge, University of East Anglia. B) National Borders: a) „Shades of the East: “Orientalism” and/as Religious Regional “Nationalism” in The Buke of the Howlat and The Flyting of Dunbar and Kennedy‟, Iain Macleod Higgins, University of Victoria . b) „The „theivis of Liddisdaill‟ and the patriotic hero: contrasting perceptions of the „wickit‟ Borderers in late medieval poetry and ballads‟, Anna Groundwater, University of Edinburgh 1 c) „The Literary Contexts of „Scotish Field‟, Thorlac Turville-Petre, University of Nottingham. -

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland

The Culture of Literature and Language in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland 15th International Conference on Medieval and Renaissance Scottish Literature and Language (ICMRSLL) University of Glasgow, Scotland, 25-28 July 2017 Draft list of speakers and abstracts Plenary Lectures: Prof. Alessandra Petrina (Università degli Studi di Padova), ‘From the Margins’ Prof. John J. McGavin (University of Southampton), ‘“Things Indifferent”? Performativity and Calderwood’s History of the Kirk’ Plenary Debate: ‘Literary Culture in Medieval and Renaissance Scotland: Perspectives and Patterns’ Speakers: Prof. Sally Mapstone (Principal and Vice-Chancellor of the University of St Andrews) and Prof. Roger Mason (University of St Andrews and President of the Scottish History Society) Plenary abstracts: Prof. Alessandra Petrina: ‘From the margins’ Sixteenth-century Scottish literature suffers from the superimposition of a European periodization that sorts ill with its historical circumstances, and from the centripetal force of the neighbouring Tudor culture. Thus, in the perception of literary historians, it is often reduced to a marginal phenomenon, that draws its force solely from its powers of receptivity and imitation. Yet, as Philip Sidney writes in his Apology for Poetry, imitation can be transformed into creative appropriation: ‘the diligent imitators of Tully and Demosthenes (most worthy to be imitated) did not so much keep Nizolian paper-books of their figures and phrases, as by attentive translation (as it were) devour them whole, and made them wholly theirs’. The often lamented marginal position of Scottish early modern literature was also the key to its insatiable exploration of continental models and its development of forms that had long exhausted their vitality in Italy or France. -

1427 to 1453

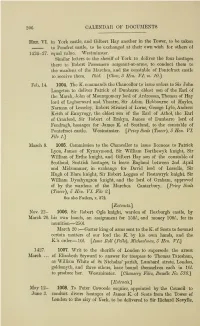

206 CALENDAE OF DOCUMENTS Hen. VI. in York castle, and Gilbert Hay another in the Tower, to be taken to Pomfret castle, to be exchanged at their own wish for others of 1426-27. equal value. Westminster. Similar letters to the sheriff of York to deliver the four hostages there to Eobert Passemere sergeant-at-arms, to conduct them to the wardens of the Marches, and the constable of Pontefract castle to receive them. IMd. {^Closc, 5 Hen. VI. m. JO.] Feb. 14. 1004. The K. commands the Chancellor to issue orders to Sir John Langeton to deliver Patrick of Dunbarre eldest son of the Earl of the March, John of Mountgomery lord of Ardrossan, Thomas of Hay lord of Loghorward and Yhestre, Sir Adam Hebbourne of Hayles, Norman of Lesseley, Eobert Stiward of Lome, George Lyle, Andrew Keith of Ennyrugy, the eldest son of the Earl of Athol, the Earl of Crauford, Sir Eobert of Erskyn, James of Dunbarre lord of Fendragh, hostages for James K. of Scotland, to the constable of Pontefract castle. Westminster. {^Privy Seals (Toiuer), 5 Hen. VI. File I] March 8. 1005. Commission to the Chancellor to issue licences to Patrick Lyon, James of Kynnymond, Sir William Borthewyk knight, Sir William of Erthe knight, and Gilbert Hay son of the constable of Scotland, Scottish hostages, to leave England between 2nd April and Midsummer, in exchange for David lord of Lesselle, Sir Hugh of Blare knight. Sir Eobert Loggan of Eestawryk knight, Sir William Dysshyngton knight, and the lord of Graham, approved of by the wardens of the Marches. -

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series

SCOTTISH TEXT SOCIETY Old Series Skeat, W.W. ed., The kingis quiar: together with A ballad of good counsel: by King James I of Scotland, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 1 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 2 (1883) Gregor, W. ed., Ane treatise callit The court of Venus, deuidit into four buikis. Newlie compylit be Iohne Rolland in Dalkeith, 1575, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 3 (1884) Small, J. ed., The poems of William Dunbar. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 4 (1893) Cody, E.G. ed., The historie of Scotland wrytten first in Latin by the most reuerend and worthy Jhone Leslie, Bishop of Rosse, and translated in Scottish by Father James Dalrymple, religious in the Scottis Cloister of Regensburg, the zeare of God, 1596. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 5 (1888) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 6 (1889) Moir, J. ed., The actis and deisis of the illustere and vailzeand campioun Schir William Wallace, knicht of Ellerslie. By Henry the Minstrel, commonly known ad Blind Harry. Vol. II, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 7 (1889) McNeill, G.P. ed., Sir Tristrem, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 8 (1886) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. I, Scottish Text Society, Old Series, 9 (1887) Cranstoun, J. ed., The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie. Vol. -

Gavin Douglas's Aeneados: Caxton's English and 'Our Scottis Langage' Jacquelyn Hendricks Santa Clara University

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 43 | Issue 2 Article 21 12-15-2017 Gavin Douglas's Aeneados: Caxton's English and 'Our Scottis Langage' Jacquelyn Hendricks Santa Clara University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons, Medieval Studies Commons, and the Other Classics Commons Recommended Citation Hendricks, Jacquelyn (2017) "Gavin Douglas's Aeneados: Caxton's English and 'Our Scottis Langage'," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 43: Iss. 2, 220–236. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol43/iss2/21 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GAVIN DOUGLAS’S AENEADOS: CAXTON’S ENGLISH AND "OUR SCOTTIS LANGAGE" Jacquelyn Hendricks In his 1513 translation of Virgil’s Aeneid, titled Eneados, Gavin Douglas begins with a prologue in which he explicitly attacks William Caxton’s 1490 Eneydos. Douglas exclaims that Caxton’s work has “na thing ado” with Virgil’s poem, but rather Caxton “schamefully that story dyd pervert” (I Prologue 142-145).1 Many scholars have discussed Douglas’s reaction to Caxton via the text’s relationship to the rapidly spreading humanist movement and its significance as the first vernacular version of Virgil’s celebrated epic available to Scottish and English readers that was translated directly from the original Latin.2 This attack on Caxton has been viewed by 1 All Gavin Douglas quotations and parentheical citations (section and line number) are from D.F.C. -

Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 35 | Issue 1 Article 12 2007 Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth- Century Scottish Literature Sally Mapstone St. Hilda's College, Oxford Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Mapstone, Sally (2007) "Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 35: Iss. 1, 131–155. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol35/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sally Mapstone Drunkenness and Ambition in Early Seventeenth-Century Scottish Literature Among the voluminous papers of William Drummond of Hawthomden, not, however with the majority of them in the National Library of Scotland, but in a manuscript identified about thirty years ago and presently in Dundee Uni versity Library, 1 is a small and succinct record kept by the author of significant events and moments in his life; it is entitled "MEMORIALLS." One aspect of this record puzzled Drummond's bibliographer and editor, R. H. MacDonald. This was Drummond's idiosyncratic use of the term "fatall." Drummond first employs this in the "Memorialls" to describe something that happened when he was twenty-five: "Tusday the 21 of Agust [sic] 1610 about Noone by the Death of my father began to be fatall to mee the 25 of my age" (Poems, p. -

Aberdeen and St Andrews Nicola Royan

St Andrews and Aberdeen 20: Aberdeen and St Andrews Nicola Royan (University of Nottingham) Introduction A thousand thre hundreth fourty and nyne Fra lichtare was þe suet Virgyne, lichtare – delivered of a child In Scotland þe first pestilens Begouth, of sa gret violens That it wes said of liffand men liffand - living The third part it distroyit þen; And eftir þat in to Scotland A зere or mare it wes wedand. wedand - raging Before þat tyme wes neuer sene In Scotland pestilens sa keyne: keyne- keen For men, and barnis and wemen, It sparit nocht for to quell then.1 Thus Andrew of Wyntoun (c.1350-c.1422) recorded the first outbreak of the Black Death in Scotland. Modern commentators set the death toll at between a quarter and a third of the population, speculating that Scotland may not have suffered as badly as some other regions of Europe.2 Nevertheless, it had a significant effect. Fordun’s Gesta discusses its symptoms, but its full impact on St Andrews comes to us through Walter Bower’s lament on the high loss among the cathedral’s canons.3 In Aberdeen, in contrast, there survive detailed burgh records regarding the process of isolating sufferers: that these relate to the outbreak of 1498 indicates that the burgesses had learned some epidemiological lessons from previous outbreaks and were willing to act on corporate responsibility.4 These responses nicely differentiate the burghs. On the north-east coast of Fife, St Andrews was a small episcopal burgh. From the top of St Rule’s tower (see above), it is easy to see to the north, the bishops’ castle substantially rebuilt by Bishop Walter Traill (1385-1401), the mouth of the river Eden, and beyond that the Firth of Tay; to the west, away from the sea, the good farmland in the rolling hills and valley of the Howe of Fife; to the east, the present harbour. -

The Private and Public Religion of David II of Scotland, 1329-71

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Stirling Online Research Repository Christian Days and Knights: The Religious Devotions and Court of 1 David II of Scotland, 1329-71. Michael Penman Abstract This article surveys the development of the religious devotions and court life of David II of Scotland (1329- 71). Using contemporary government and chronicle sources it discusses David’s favour to a wide range of chivalric and pious causes, many with special personal resonance for the second Bruce king. This patronage attracted widespread support for his kingship after 1357. However, such interests also had political motivation for David, namely his agenda of securing a peace deal with Edward III of England and overawing his Scottish magnate opponents. His political circumstances meant that his legacy of chivalric and religious patronage were obscured after his early death. Accepted for publication in Historical Research by Wiley-Blackwell. Edward III (1327-77) was celebrated by late medieval writers as a king in the biblical style: as an exemplar of Christian virtue, a warrior and generous patron of the church, founder of several royal chapels and of the knights’ Order of St George. Similarly, Philip VI of France (1328-50) received praise for the time and energy he dedicated to attempting to organise a Pan-European crusade to recover the Holy Land, attracting hundreds of European knights, Counts, Princes and lesser kings to his realm in the 1330s. Meanwhile, Robert I of Scotland (1306-29) -

First Series, 1883-1910 1 the Kingis Quair, Ed. W. W. Skeat 1884 2 The

First Series, 1883-1910 1 The Kingis Quair, ed. W. W. Skeat 1884 2 The Poems of William Dunbar I, ed. John Small 1893 3 The Court of Venus, by John Rolland. 1575, ed. Walter Gregor 1884 4 The Poems of William Dunbar II, ed. John Small 1893 5 Leslie’s Historie of Scotland I, ed. E.G. Cody 1888 6 Schir William Wallace I, ed. James Moir 1889 7 Schir William Wallace II, ed. James Moir 1889 8 Sir Tristrem, ed. G.P. McNeill 1886 9 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie I, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 10 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie II, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 11 The Poems of Alexander Montgomerie III, ed. James Cranstoun 1887 12 The Richt Vay to the Kingdome of Heuine by John Gau, ed. A.F. Mitchell 1888 13 Legends of the Saints I, ed. W.M. Metcalfe 1887 14 Leslie’s History of Scotland II, ed. E.G. Cody 1895 15 Niniane Winzet’s Works I, ed. J. King Hewison 1888 16 The Poems of William Dunbar III, ed. John Small, Introduction by Æ.J.G. Mackay 1893 17 Schir William Wallace III, ed. James Moir 1889 18 Legends of the Saints II, ed. W.M. Metcalfe 1888 19 Leslie’s History of Scotland III, ed. E.G. Cody 1895 20 Satirical Poems of the Time of the Reformation I, ed. James Cranstoun REPRINT 1889 21 The Poems of William Dunbar IV, ed. John Small 1893 22 Niniane Winzet’s Works II, ed. J. King Hewison 1890 23 Legends of the Saints III, ed. -

Makar's Court

Culture and Sport Committee 2.00pm, Monday, 20 March 2017 Makars’ Court: Proposed Additional Inscriptions Item number Report number Executive/routine Wards All Executive Summary Makars’ Court at the Writers’ Museum celebrates the achievements of Scottish writers. This ongoing project to create a Scottish equivalent of Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey was the initiative of the former Culture and Leisure Department, in association with the Saltire Society and Lothian and Edinburgh Enterprise Ltd, as it was then known. It was always the intention that Makars’ Court would grow and develop into a Scottish national literary monument as more writers were commemorated. At its meeting on 10 March 1997 the then Recreation Committee established that the method of selecting writers for commemoration would involve the Writers’ Museum forwarding sponsorship requests for commemorating writers to the Saltire Society, who would in turn make a recommendation to the Council. The Council of the Saltire Society now recommends that two further applications be approved, to commemorate William Soutar (1898-1943) – poet and diarist, and George Campbell Hay (1915-1984) – poet. Links Coalition Pledges P31 Council Priorities CP6 Single Outcome Agreement SO2 Report Makar’s Court: Proposed Additional Inscriptions 1. Recommendations 1.1 It is recommended that the Committee approves the addition of the proposed new inscriptions to Makars’ Court. 2. Background 2.1 Makars’ Court at the Writers’ Museum celebrates the achievements of Scottish writers. This ongoing project to create a Scottish equivalent of Poets’ Corner at Westminster Abbey was the initiative of the former Culture and Leisure Department, in association with the Saltire Society and Lothian and Edinburgh Enterprise Ltd, as it was then known. -

114638654.23.Pdf

SCS ST£S!.lf-lj- ZTbe Scottish ZTcyt Society GILBERT OF THE HAYE’S PROSE MANUSCRIPT I. THE BUKE OF THE LAW OF ARMYS V" GILBERT OF THE HAYE’S PROSE MANUSCRIPT (A.D. 1456) VOLUME I. THE BUKE OF THE LAW OF ARMYS OR BUKE OF BATAILLIS EDITED WITH INTRODUCTION BY J. H. STEVENSON for tlje Societg bg WILLIAM BLACKWOOD AND SONS EDINBURGH AND LONDON 1901 All Rights reserved PREFATORY NOTE. To the courtesy of the Honourable Mrs Maxwell-Scott of Abbotsford, in the first place, the Scottish Text Society is indebted for permission to print the Haye Prose Manuscript. The Dean and Council of the Faculty of Advocates, as trustees of the older Abbotsford Library, of which the volume forms a part, readily added their consent. The making of the transcript for the use of the printer was intrusted to the Rev. Walter MacLeod, but as the editor has carefully collated the transcript with both the print and the MS., he desires to take his full share of the responsibility of any mistakes which may still have crept into the print. J. H. S. CONTENTS OF THE FIRST VOLUME. INTRODUCTION— page 1. DESCRIPTION OF THE MANUSCRIPT . vii 2. THE TRANSLATOR ..... Xxiii 3. THE FORTUNES OF THE MANUSCRIPT . XXXvi 4. THE PLACE OF HAYE’S MS. IN EARLY SCOTTISH PROSE ...... lii 5. THE PRINCIPLES OF THE EDITING . lix HONORS BONET AND HIS ‘ ARBRE DES BATAILLES ’ . Ixiv THE BUKE OF THE LAW OF ARMYS— INTITULACIOUN ..... I RUBRICS OF FIRST PART .... I translator’s INTRODUCTION ... 2 AUTHOR’S PROLOGUE ..... 2 FIRST PART OF THE BOOK ... -

Traditions of King Duncan I Benjamin T

Studies in Scottish Literature Volume 25 | Issue 1 Article 8 1990 From Senchus to histore: Traditions of King Duncan I Benjamin T. Hudson Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hudson, Benjamin T. (1990) "From Senchus to histore: Traditions of King Duncan I," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 25: Iss. 1. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/ssl/vol25/iss1/8 This Article is brought to you by the Scottish Literature Collections at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in Scottish Literature by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Benjamin T. Hudson From Senchus to histore: Traditions of King Duncan I The kings of Scotland prior to the reign of Malcolm III, popularly known as Malcolm Carunore (Malcolm "Bighead") have rarely been con sidered in connection with Scottish historical literature. Macbeth, largely due to Shakespeare's drama, has been the exception. For the medieval period alone, Nora Chadwick's examination of the Macbeth legend showed that a number of literary traditions, both native and foreign, can be detected in later medieval literature. 1 Macbeth was not alone in hav ing a variety of legends cluster about his memory; his historical and liter ary contemporary Duncan earned his share of legends too. This can be seen in a comparison of the accounts about Duncan preserved in historical literature, such as the Chroniea Gentis Seotorum of John of Fordun and the Original Chronicle of Scotland by Andrew of Wyntoun.2 Such a com- INora Chadwick, "The Story of Macbeth," Scottish Gaelic Studies (1949), 187-221; 7 (1951), 1-25.