Children Fall 2011

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020–21 Student Handbook MS Degree Programs Graduate Certificate Programs Students at Large Contents Click on a Section to Navigate

Graduate School in Child Development 2020–21 Student Handbook MS Degree Programs Graduate Certificate Programs Students at Large Contents Click on a section to navigate. Reservation of rights 2 Registration/student records policies and procedures 82 Coronavirus (COVID-19) 3 Academic records 82 Add/drop procedures 82 Academic calendar 2020–21 4 Audited courses 82 Welcome to Erikson Institute 6 Change of address 82 Changing programs 83 Our mission and values 7 Course substitution 83 Holds on registration 83 Admission requirements 9 Immunization records 83 Incomplete policy 84 Master’s degree programs 11 Independent study 84 Leave of absence 85 Master’s degree course descriptions 31 Official Institute communications 85 Preferred-chosen name 86 Graduate certificate programs 51 Readmission 86 Registration 86 Certificate program course descriptions 56 Repeated courses 86 Academic policies and procedures 61 Review of records 86 Transcript requests 88 Academic integrity 61 Transfer credit 88 Academic grievance procedure 63 Withdrawing from Erikson 89 Academic probation and warning: continuing students 64 Academic probation: exiting academic probation 65 Student rights and responsibilities 90 Attendance policy and classroom decorum 65 General 90 Comprehensive examination 66 Finance 90 Conditional admission: new students 67 Registration 90 Conferral of degrees and certificates 67 Student conduct 91 Continuous enrollment policy 67 Student disciplinary process 91 Copyright protection for work created by others 68 Technical standards 93 Copyright protection -

Admiral 11X17 Newsletter (TEMPLATE).Qxd 3/20/13 3:08 PM Page 1

IEJC_Newsletter2013_FINAL_3216 - Admiral 11x17 Newsletter (TEMPLATE).qxd 3/20/13 3:08 PM Page 1 SPRING 2013 CIVIL LEGAL AID PROGRAMS • By obtaining protective orders, divorces, child custody and legal recognition for noncitizens experiencing abuse, providers MEASURE THEIR IMPACT avoided $9.4 million in costs associated with domestic violence Study Shows Economic Benefits of to individuals. • Overall, each dollar spent on Illinois legal aid by governments Civil Legal Aid and private donors was associated with $1.80 in economic benefits for legal aid clients or other Illinoisans. Total economic Local foundations partnered to benefits from cases closed in 2010 in areas considered by the study release a report last May to exceeded spending on legal aid by $32.1 million. 1 0 6 0 6 L I , o g a c i h C inform policymakers and other 0 2 8 e t i u S , . e v A n o s t e t S . N 0 8 1 Across Illinois, nonprofit legal aid providers offer free or low-cost legal stakeholders about the tangible advice and representation to low-income, disadvantaged Illinoisans n o i t a d n u o F e c i t s u J l a u q E economic benefits of legal aid. with civil legal problems who cannot afford a lawyer. These legal aid s i o n i l l I e h t f o t c e j o r P A The report, Legal Aid in Illinois: providers afford access to the justice system for clients facing threats N G I A P M A C S I O N I L L I Selected Social and Economic to the health and safety of themselves and their families. -

Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows Program

Barbara Cohort Bowman Leadership 2017 Fellows The Early Childhood Leadership Academy is pleased to present the policy memos developed by the 2017 Policy Cohort of the Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows Program. Memos SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Support The Early Childhood Leadership Academy at Erikson Institute gratefully acknowledges the support and generosity of The Irving B. Harris Foundation for its support of the Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows program. BARBARA BOWMAN We are honored to have the program named after one of Erikson Institute’s founders, Barbara Taylor Bowman. Barbara’s legacy as an education activist, policy adviser, and early childhood practitioner matches the characteristics of the fellows this program aims to attract. Furthermore, her dedication to ensuring that diversity and equity are mutually reinforced provides the framework that supports the entire program experience. This effort draws from Erikson’s mission-driven work to ensure a future in which all children have equitable opportunities to realize their full potential through leadership and policy influence. Special thanks to President and CEO, Geoffrey A. Nagle for his continuous commitment to the program. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Participating Organizations TABLE OF CONTENTS ACCESS ..........................................................................................................1 CARISA HURLEY ...................................................................................................... 1 CINDY LA .............................................................................................................. -

Chicago College of Performing Arts) Provided the Foundation for Successes I’Ve Enjoyed Both in Life and in Music

FALL 2005 REVIEW RA MAGAZINEO FOR ALUMNI AOND FRIENDS OF RSEVELTOOSEVELT UNIVERSITY Roosevelt’s World class iolinists V page 4 V& iolins AKING A DIFFERENCE M in the lives that follow “My education at Roosevelt’s Chicago Musical College (now The Music Conservatory of Chicago College of Performing Arts) provided the foundation for successes I’ve enjoyed both in life and in music. Because of my strong feelings for the mission of Roosevelt and in appreciation for the skills and musical inspiration I received, I wanted to remember the University.” Humbert “Bert” J. Lucarelli (BM ‘59) Humbert “Bert” J. Lucarelli has distinguished himself of Hartford in West Hartford, Conn, and the founder as one of America’s foremost musicians. He has been and president of Oboe International, Inc., a non-profit hailed as America’s leading oboe recitalist. Bert has foundation whose principal activity has been presenting performed extensively throughout the world with major the New York International Competition for solo oboists. symphony orchestras, and in 2002 he was the first Like many other Roosevelt University alumni, this American oboist to be invited to perform and teach at internationally renowned oboe recitalist has made the Central Conservatory in Beijing, China. Bert is a commitment to his alma mater in his estate plans. professor of oboe at the Hartt School at the University Fred Barney Planned and Major Gifts Office of Institutional Advancement U L T N E I Roosevelt University V V E E 430 S. Michigan Avenue, Rm. 827 R S S O Chicago, IL 60605 I T O Y Phone: (312) 341-6455 R 1 9 4 5 Fireside Circle Fax: (312) 341-6490 Toll-free: 1-888-RU ALUMS E-mail: [email protected] FALL 2005 REVIEW RRA MAGAZINEOO FOR ALUMNI AONDO FRIENDS OF RSSOOSEVELTEVEEVE UNIVERSITY LLTT FOCUS SNAPSHOTS VIOLIN VIRTUOSOS RU PARTNERS WITH SOCIAL TEACH & PERFORM ....................... -

December 2019 Higher Education Cohorts

December 2019 Higher Education Cohorts PD290© 2019 INCCRRA Cohort Pathways in Illinois: Innovative Models Supporting the Early Childhood Workforce Institutions of higher education in Illinois have long implemented collaborative, innovative strategies to support credential and degree attainment. The Illinois Governor’s Office of Early Childhood Development (GOECD) is invested in supporting flexible, responsive pathways to credentials and degree attainment for early childhood practitioners, as early childhood practitioners equipped with appropriate knowledge and skills are critical to developing and implementing high-quality early childhood experiences for young children and their families. At the same time, the State of Illinois is eager to ensure that pathways developed not only support entry into and progression within the field, but also are inclusive of and responsive to programs’ diverse and experienced staff members who have not yet attained new credentials and/or degrees. The purpose of this paper is to highlight the innovative work of Illinois institutions of higher education in creating cohort pathways that are responsive to the needs of the current and future early childhood workforce. Cohort models are commonly defined as a group of students moving through a program in a cohesive fashion with support provided for the overall healthy functioning of the group. In this paper, the highlighted cohort pathways focus on additional supports provided to cohort model participants (social and practical) as well as innovative model designs. Understanding these unique cohort pathways requires a fundamental understanding of existing credential and degree pathways in Illinois, the current early childhood education (ECE) workforce, present challenges in growing an ECE workforce, and research highlighting 1 innovative components of cohort models. -

Sophia Denise Dorsey King Home Address

From: [email protected] To: ward4candidate Subject: City of Chicago - Aldermanic Vacancy Application Form Date: Friday, March 04, 2016 4:40:34 PM Application submitted online Name: Sophia Denise Dorsey King Home Address: Home Phone: Employer: N/A Title/Position: N/A Business Address: N/A Business Phone: N/A Birth Date: Place of Birth: Boulder, Colorado Spouse's Name: Have you ever been a candidate for public office? No If yes, please list office: Education: Northwestern University - Master of Science, Education and Social Policy University of Illinois – Champaign Urbana – Bachelor of Science, Chemistry Government Experience: Appointed by then 4th Ward Alderman Toni Preckwinkle to the Kenwood Park Advisory Council (KPAC) after a conflict arose in the community over Park usage. Community Involvement: TITO (The It’s Time Organization), Founding Board Member and Strategic Plan Leader Mission: To access funds from large public and private sources to invest in programs that will have the greatest short and long term impact on gun violence in the 3rd, 4th, and 5th wards. Harriet’s Daughters, President and Founder Vision: Eliminating all disparities in employment and wealth for African American adults and youth. Mission: Harriet’s Daughters is a group of professional women working collectively with peer organizations to advocate for, create and support policies and processes that secure employment and wealth creation opportunities for African-American communities. Harriet’s Daughters met with the Governor and Mayor on a variety of topics including more parity in procurement and procurement opportunities. We have been particularly focused on the amount of waivers issued. Harriet’s Daughters collaborates with other stakeholders to leverage job opportunities for African Americans on the Southside of Chicago like Skills for Chicagoland’s Future, the Incubator at University of Chicago and North Lawndale Employment Network. -

Illinois Commission on Equitable Early Childhood Education and Care Funding: Member Bios

Illinois Commission on Equitable Early Childhood Education and Care Funding: Member Bios Jesse Ruiz was named Deputy Governor for Education in January 2019. Ruiz came to the Governor’s Office after over 20 years as a corporate lawyer at the firm Drinker, Biddle, and Reath, where he focused on mergers and acquisitions. Throughout his law career, Ruiz also served in many public service roles including Chair of the Illinois State Board of Education, President of the Chicago Park District, and interim CEO of Chicago Public Schools. Ruiz is also the current President of the Chicago Bar Association. He received his Bachelor of Arts in Economics from the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign and his JD from the University of Chicago Law School. Andy Manar represents the 48th Senate district encompassing parts of Sangamon, Christian, Macoupin, Madison, Macon, and Montgomery counties. He was a driving force behind the passage of the K-12 Evidence-Based Funding Formula (EBF). Prior to his tenure in the General Assembly, Manar served as Mayor of Bunker Hill and Chairman of the Macoupin County Board. He received his Bachelor of History from Southern Illinois University Edwardsville, where he also received his teaching license. Barbara Flynn Currie holds the record for the longest serving woman in the Illinois General Assembly, with 40 years of experience, including over 20 years as Majority Leader. She also helped steer the state’s EBF efforts and is known for her tireless advocacy on many progressive issues in Illinois. She received her bachelor’s degree and Master of Political Science at the University of Chicago. -

THE STUDENT ACCESS BILL House Sponsors

SUPPORT SB 2196: THE STUDENT ACCESS BILL House Sponsors: Hern an d ez -Prit ch ard -A m m on s-M ay field -Gu z z ard i Senate Sponsors: M art in ez -M cGu ire -St ean s-San d o v al-Hast in gs Provide Equal Access t o Financial Aid at 4 -Year Public Universities The Student ACCESS bill will provide legal authority to 4-year public universities in Illinois to provide financial aid to undocumented students who already qualify for in-state tuition. Undocumented students are currently ineligible to receive federal student aid, Pell grants, Illinois’ MAP grant and other forms of state-based financial aid. However, federal law allows individual state legislatures to offer undocumented students eligibility for state financial aid. Passage of the Student ACCESS bill would allow 4-year public universities to offer financial aid to every student enrolled at their institution on a competitive basis. The legislation will not, however, make undocumented students eligible to apply for the MAP grant. The Student ACCESS bill is revenue neutral! The legislation does not have a fiscal impact because it does not require the state to appropriate additional resources for higher education or increase spending for state-funded scholarship programs. The bill simply provides 4-year public universities the legal authority to offer financial aid to undocumented students who already qualify for in-state tuition. The legislation does not create an entitlement, a new state scholarship program or provide undocumented students with a competitive advantage when applying for financial aid. How many students would this apply to? The University of Illinois at Chicago estimates that the Student ACCESS bill would provide new scholarship opportunities for roughly 1,500 undocumented students across all 4-year public universities in Illinois. -

2019–20 Student Handbook Phd Program Contents Click on a Section to Navigate

2019–20 Student Handbook PhD Program Contents Click on a section to navigate. Academic calendar 2019–20 2 Registration/student records policies and procedures 33 Welcome to Erikson Institute 3 Academic records 33 Add/drop procedures 33 Our mission and values 4 Audited courses 33 Admission requirements 6 Change of address 34 Change of name 34 Degree requirements 8 Extension of time 34 Holds on registration 35 PhD course descriptions 12 Immunization records 35 Incomplete policy 35 Academic policies and procedures 14 Independent study 36 Academic integrity 14 Leave of absence 36 Academic grievance procedure 16 Official communications 37 Attendance and classroom decorum 17 Preferred/chosen name 37 Conferral of degrees at Loyola 18 Readmission 38 Copyright protection for work created by others 18 Registration 38 Copyright protection for work created by students 18 Repeated courses 38 Course and end-of-year evaluations 19 Review of records — Erikson Institute 38 Credit hour policy at Erikson 19 Review of records — Loyola University Chicago 40 English-language requirement 20 Transcript requests 42 Final examinations 21 Transfer credit 42 Freedom of inquiry 21 Withdrawing from the doctoral program 43 Good academic standing 21 Grading system at Loyola 21 Erikson student rights and responsibilities 44 Internships 21 General 44 Probation 22 Finance 44 Registration 44 Erikson campus policies and procedures 23 Student conduct 44 Building access information 23 Student disciplinary process 45 Concealed carry policy 23 Discrimination and harassment, including -

Lead in Multiple Fields

76129_P18_23_p.22-23 Soldiers Story 9/11/13 10:28 AM Page 1 LAW SCHOOL GRADUATES LEAD IN MULTIPLE FIELDS By Robin I. Mordfin 18 THEUNIVERSITYOFCHICAGOLAWSCHOOL I F A L L 2 0 1 3 76129_P18_23_p.22-23 Soldiers Story 9/11/13 10:28 AM Page 2 s the University of Chicago Law School gets ready to launch two major leadership initiatives—the A Doctoroff Business Leadership Program and the Kapnick Leadership and Professionalism Program—it is an opportune time to reflect on the tremendous role our graduates have played in leading a wide variety of public and private organizations and enterprises. The University of Chicago Law School is much smaller than most of its peer schools and therefore has many fewer alumni. You wouldn’t know that, however, by surveying the top ranks of law, business, and government. Chicago’s groundbreaking commitment to interdisciplinary education has created generations of inventive thinkers and legal trailblazers who lead in countless fields. Our alumni lead in Congress, in the executive branch, and in the Department of Justice. They are judges, philanthropists, educators, reformers, CEOs, and innovators. Chicago’s enthusiasm for the life of the mind, and the belief that ideas matter, fosters graduates who work to solve societal problems in countless ways and in endlessly varied fields. Amy Klobuchar, ’85, became the first woman elected to represent Minnesota in the US Senate in 2006. She is vice chair of the Joint Economic Committee and is a member of both the President’s Export Council and the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation. -

Course / Instructor(S)

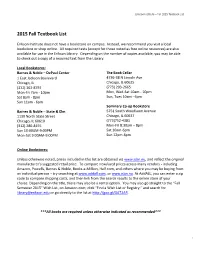

Erikson Institute – Fall 2015 Textbook List 2015 Fall Textbook List Erikson Institute does not have a bookstore on campus. Instead, we recommend you visit a local bookstore or shop online. All required texts (except for those noted as free online resources) are also available for use in the Erikson Library. Depending on the number of copies available, you may be able to check out a copy of a required text from the Library. Local Bookstores: Barnes & Noble – DePaul Center The Book Cellar 1 East Jackson Boulevard 4736-38 N Lincoln Ave Chicago, IL Chicago, IL 60625 (312) 362-8792 (773) 293-2665 Mon-Fri 7am - 10pm Mon, Wed-Sat 10am - 10pm Sat 8am - 8pm Sun, Tues 10am - 6pm Sun 11am - 6pm Seminary Co-op Bookstore Barnes & Noble – State & Elm 5751 South Woodlawn Avenue 1130 North State Street Chicago, IL 60637 Chicago, IL 60610 (773)752-4381 (312) 280-8155 Mon-Fri 8:30am – 8pm Sun 10:00AM-9:00PM Sat 10am-6pm Mon-Sat 9:00AM-9:00PM Sun 12pm-6pm Online Bookstores: Unless otherwise noted, prices included in this list are obtained via www.isbn.nu, and reflect the original manufacturer’s suggested retail price. To compare new/used prices across many vendors - including Amazon, Powells, Barnes & Noble, Books-a-Million, Half.com, and others where you may be buying from an individual person – try searching at www.addall.com, or www.isbn.nu. At AddALL, you can enter a zip code to compare shipping costs, and then link from the search results to the online store of your choice. -

On-Campus Master's Degree Programs 2017–18 Academic Year

On-Campus Master’s Degree Programs 2017–18 Academic Year Tracy Vega M.S.W., 2016 Caregiver Support Team Clinician Association House of Chicago Earning your master’s degree at Erikson Institute is the best preparation you can get for the career that lies ahead of you. The work you’ve chosen—ensuring that the children of today grow up to be the healthy, happy, responsible, and productive adults of tomorrow—is not easy, and it couldn’t be more important. You owe it to yourself to choose an education that’s equal to the task. An education that enables you to • Develop the skills to be a leader in a variety of social service and early childhood fields. • Gain a deep, research-based understanding of child development and family functioning. • Challenge yourself as you examine your knowledge, actions, and assumptions. • Join a close-knit community of professionals passionate about children and families, just like you are. • Have the greatest impact you can on the lives of the children and families you serve. An Erikson education is all of this and more. Brian Puerling M.S. in Early Childhood Education, 2011 Director of Education Technology Catherine Cook School, Chicago Learn how children develop and why it matters At Erikson, whether you choose our master’s degree program in child development, social work, or early childhood education, you’ll learn how children develop and the complex contextual factors that shape development. You’ll learn about specific developmental domains, including physical/motor, cognitive, social, emotional, and communicative/language, and how developmental processes weave these domains together.