December 2019 Higher Education Cohorts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Fall 2019 Enrollments in Illinois Higher Education

Item #I-1 December 10, 2019 PRELIMINARY FALL 2019 ENROLLMENTS IN ILLINOIS HIGHER EDUCATION Submitted for: Information. Summary: This report summarizes preliminary fall-term 2019 headcount and full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollments at degree-granting colleges and universities in Illinois. The report also summarizes enrollments in remedial/developmental courses during the 2018- 2019 academic year. Fall 2019 preliminary headcount enrollments at degree-granting institutions total 720,215 and preliminary FTE enrollments total 541,187. Brisk Rabbinical College did not respond to the survey and therefore was excluded from the report. Action Requested: None 323 Item #I-1 December 10, 2019 PRELIMINARY FALL 2019 ENROLLMENTS IN ILLINOIS HIGHER EDUCATION This report summarizes preliminary fall-term 2019 headcount and full-time-equivalent (FTE) enrollments at colleges and universities in Illinois. It also includes enrollments in remedial/developmental courses for Academic Year 2018-2019. Fall-term enrollments provide a “snapshot” of Illinois higher education enrollments on the 10th day, or census date, of the fall term. It should be noted that two colleges, Brisk Rabbinical College did not respond to the survey and was therefore excluded from the report. Preliminary fall 2018 enrollments by sector Including enrollments at out-of-state institutions authorized to operate in Illinois, fall 2019 preliminary headcount enrollments at degree-granting institutions total 720,215 (see Table 4 for institutional level data). Fall 2019 FTE enrollments total 541,187. -

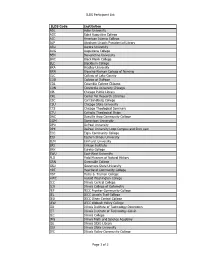

ILDS Participant List ILDS Code Institution ADL Adler University

ILDS Participant List ILDS Code Institution ADL Adler University AGC Saint Augustine College AIC American Islamic College ALP Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library ARU Aurora University AUG Augustana College BEN Benedictine University BHC Black Hawk College BLC Blackburn College BRA Bradley University BRN Blessing-Rieman College of Nursing CLC College of Lake County COD College of DuPage COL Columbia College Chicago CON Concordia University Chicago CPL Chicago Public Library CRL Center for Research Libraries CSC Carl Sandburg College CSU Chicago State University CTS Chicago Theological Seminary CTU Catholic Theological Union DAC Danville Area Community College DOM Dominican University DPU DePaul University DPX DePaul University Loop Campus and Rinn Law ECC Elgin Community College EIU Eastern Illinois University ELM Elmhurst University ERI Erikson Institute ERK Eureka College EWU East-West University FLD Field Museum of Natural History GRN Greenville College GSU Governors State University HRT Heartland Community College HST Harry S. Truman College HWC Harold Washington College ICC Illinois Central College ICO Illinois College of Optometry IEF IECC Frontier Community College IEL IECC Lincoln Trail College IEO IECC Olney Central College IEW IECC Wabash Valley College IID Illinois Institute of Technology-Downtown IIT Illinois Institute of Technology-Galvin ILC Illinois College IMS Illinois Math and Science Academy ISL Illinois State Library ISU Illinois State University IVC Illinois Valley Community College Page 1 of 3 ILDS Participant List -

2020–21 Student Handbook MS Degree Programs Graduate Certificate Programs Students at Large Contents Click on a Section to Navigate

Graduate School in Child Development 2020–21 Student Handbook MS Degree Programs Graduate Certificate Programs Students at Large Contents Click on a section to navigate. Reservation of rights 2 Registration/student records policies and procedures 82 Coronavirus (COVID-19) 3 Academic records 82 Add/drop procedures 82 Academic calendar 2020–21 4 Audited courses 82 Welcome to Erikson Institute 6 Change of address 82 Changing programs 83 Our mission and values 7 Course substitution 83 Holds on registration 83 Admission requirements 9 Immunization records 83 Incomplete policy 84 Master’s degree programs 11 Independent study 84 Leave of absence 85 Master’s degree course descriptions 31 Official Institute communications 85 Preferred-chosen name 86 Graduate certificate programs 51 Readmission 86 Registration 86 Certificate program course descriptions 56 Repeated courses 86 Academic policies and procedures 61 Review of records 86 Transcript requests 88 Academic integrity 61 Transfer credit 88 Academic grievance procedure 63 Withdrawing from Erikson 89 Academic probation and warning: continuing students 64 Academic probation: exiting academic probation 65 Student rights and responsibilities 90 Attendance policy and classroom decorum 65 General 90 Comprehensive examination 66 Finance 90 Conditional admission: new students 67 Registration 90 Conferral of degrees and certificates 67 Student conduct 91 Continuous enrollment policy 67 Student disciplinary process 91 Copyright protection for work created by others 68 Technical standards 93 Copyright protection -

Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows Program

Barbara Cohort Bowman Leadership 2017 Fellows The Early Childhood Leadership Academy is pleased to present the policy memos developed by the 2017 Policy Cohort of the Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows Program. Memos SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Support The Early Childhood Leadership Academy at Erikson Institute gratefully acknowledges the support and generosity of The Irving B. Harris Foundation for its support of the Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows program. BARBARA BOWMAN We are honored to have the program named after one of Erikson Institute’s founders, Barbara Taylor Bowman. Barbara’s legacy as an education activist, policy adviser, and early childhood practitioner matches the characteristics of the fellows this program aims to attract. Furthermore, her dedication to ensuring that diversity and equity are mutually reinforced provides the framework that supports the entire program experience. This effort draws from Erikson’s mission-driven work to ensure a future in which all children have equitable opportunities to realize their full potential through leadership and policy influence. Special thanks to President and CEO, Geoffrey A. Nagle for his continuous commitment to the program. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Participating Organizations TABLE OF CONTENTS ACCESS ..........................................................................................................1 CARISA HURLEY ...................................................................................................... 1 CINDY LA .............................................................................................................. -

Chicago: North Park Garage Overview North Park Garage

Chicago: North Park Garage Overview North Park Garage Bus routes operating out of the North Park Garage run primarily throughout the Loop/CBD and Near Northside areas, into the city’s Northeast Side as well as Evanston and Skokie. Buses from this garage provide access to multiple rail lines in the CTA system. 2 North Park Garage North Park bus routes are some busiest in the CTA system. North Park buses travel through some of Chicago’s most upscale neighborhoods. ● 280+ total buses ● 22 routes Available Media Interior Cards Fullbacks Brand Buses Fullwraps Kings Ultra Super Kings Queens Window Clings Tails Headlights Headliners Presentation Template June 2017 Confidential. Do not share North Park Garage Commuter Profile Gender Age Female 60.0% 18-24 12.5% Male 40.0% 25-44 49.2% 45-64 28.3% Employment Status 65+ 9.8% Residence Status Full-Time 47.0% White Collar 50.1% Own 28.9% 0 25 50 Management, Business Financial 13.3% Rent 67.8% HHI Professional 23.7% Neither 3.4% Service 14.0% <$25k 23.6% Sales, Office 13.2% Race/Ethnicity $25-$34 11.3% White 65.1% Education Level Attained $35-$49 24.1% African American 22.4% High School 24.8% Hispanic 24.1% $50-$74 14.9% Some College (1-3 years) 21.2% Asian 5.8% >$75k 26.1% College Graduate or more 43.3% Other 6.8% 0 15 30 Source: Scarborough Chicago Routes # Route Name # Route Name 11 Lincoln 135 Clarendon/LaSalle Express 22 Clark 136 Sheridan/LaSalle Express 36 Broadway 146 Inner Drive/Michigan Express 49 Western 147 Outer Drive Express 49B North Western 148 Clarendon/Michigan Express X49 Western Express 151 Sheridan 50 Damen 152 Addison 56 Milwaukee 155 Devon 82 Kimball-Homan 201 Central/Ridge 92 Foster 205 Chicago/Golf 93 California/Dodge 206 Evanston Circulator 96 Lunt Presentation Template June 2017 Confidential. -

Chicago College of Performing Arts) Provided the Foundation for Successes I’Ve Enjoyed Both in Life and in Music

FALL 2005 REVIEW RA MAGAZINEO FOR ALUMNI AOND FRIENDS OF RSEVELTOOSEVELT UNIVERSITY Roosevelt’s World class iolinists V page 4 V& iolins AKING A DIFFERENCE M in the lives that follow “My education at Roosevelt’s Chicago Musical College (now The Music Conservatory of Chicago College of Performing Arts) provided the foundation for successes I’ve enjoyed both in life and in music. Because of my strong feelings for the mission of Roosevelt and in appreciation for the skills and musical inspiration I received, I wanted to remember the University.” Humbert “Bert” J. Lucarelli (BM ‘59) Humbert “Bert” J. Lucarelli has distinguished himself of Hartford in West Hartford, Conn, and the founder as one of America’s foremost musicians. He has been and president of Oboe International, Inc., a non-profit hailed as America’s leading oboe recitalist. Bert has foundation whose principal activity has been presenting performed extensively throughout the world with major the New York International Competition for solo oboists. symphony orchestras, and in 2002 he was the first Like many other Roosevelt University alumni, this American oboist to be invited to perform and teach at internationally renowned oboe recitalist has made the Central Conservatory in Beijing, China. Bert is a commitment to his alma mater in his estate plans. professor of oboe at the Hartt School at the University Fred Barney Planned and Major Gifts Office of Institutional Advancement U L T N E I Roosevelt University V V E E 430 S. Michigan Avenue, Rm. 827 R S S O Chicago, IL 60605 I T O Y Phone: (312) 341-6455 R 1 9 4 5 Fireside Circle Fax: (312) 341-6490 Toll-free: 1-888-RU ALUMS E-mail: [email protected] FALL 2005 REVIEW RRA MAGAZINEOO FOR ALUMNI AONDO FRIENDS OF RSSOOSEVELTEVEEVE UNIVERSITY LLTT FOCUS SNAPSHOTS VIOLIN VIRTUOSOS RU PARTNERS WITH SOCIAL TEACH & PERFORM ....................... -

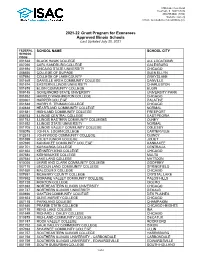

2021-22 Grant Program for Exonerees Approved Illinois Schools Last Updated July 20, 2021

1755 Lake Cook Road Deerfield, IL 60015-5209 800.899.ISAC (4722) Website: isac.org E-mail: [email protected] 2021-22 Grant Program for Exonerees Approved Illinois Schools Last Updated July 20, 2021 FEDERAL SCHOOL NAME SCHOOL CITY SCHOOL CODE 001638 BLACK HAWK COLLEGE ALL LOCATIONS 007265 CARL SANDBURG COLLEGE GALESBURG 001694 CHICAGO STATE UNIVERSITY CHICAGO 006656 COLLEGE OF DUPAGE GLEN ELLYN 007694 COLLEGE OF LAKE COUNTY GRAYSLAKE 001669 DANVILLE AREA COMMUNITY COLLEGE DANVILLE 001674 EASTERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY CHARLESTON 001675 ELGIN COMMUNITY COLLEGE ELGIN 009145 GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY UNIVERSITY PARK 001652 HAROLD WASHINGTON COLLEGE CHICAGO 003961 HARPER COLLEGE PALATINE 001648 HARRY S. TRUMAN COLLEGE CHICAGO 030838 HEARTLAND COMMUNITY COLLEGE NORMAL 001681 HIGHLAND COMMUNITY COLLEGE FREEPORT 006753 ILLINOIS CENTRAL COLLEGE EAST PEORIA 001742 ILLINOIS EASTERN COMMUNITY COLLEGES OLNEY 001692 ILLINOIS STATE UNIVERSITY NORMAL 001705 ILLINOIS VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE OGLESBY 008076 JOHN A. LOGAN COLLEGE CARTERVILLE 012813 JOHN WOOD COMMUNITY COLLEGE QUINCY 001699 JOLIET JUNIOR COLLEGE JOLIET 007690 KANKAKEE COMMUNITY COLLEGE KANKAKEE 001701 KASKASKIA COLLEGE CENTRALIA 001654 KENNEDY-KING COLLEGE CHICAGO 007684 KISHWAUKEE COLLEGE MALTA 007644 LAKE LAND COLLEGE MATTOON 010020 LEWIS AND CLARK COMMUNITY COLLEGE GODFREY 007170 LINCOLN LAND COMMUNITY COLLEGE SPRINGFIELD 001650 MALCOLM X COLLEGE CHICAGO 007691 MCHENRY COUNTY COLLEGE CRYSTAL LAKE 007692 MORAINE VALLEY COMMUNITY COLLEGE PALOS HILLS 001728 MORTON COLLEGE CICERO -

Columbia College Alumni Association Columbia College Chicago

Columbia College Chicago Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago Alumni Newsletters Alumni Winter 1988 Columbia College Alumni Association Columbia College Chicago Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/alumnae_news This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Columbia College Alumni Association (Winter 1988), Alumni Magazine, College Archives & Special Collections, Columbia College Chicago. http://digitalcommons.colum.edu/alumnae_news/35 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Alumni at Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. It has been accepted for inclusion in Alumni Newsletters by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Columbia College Chicago. 600 SOUTH MICHIGAN AVENUE CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60605-1996 Hokin is Hoppin' The aroma of cinnamon walnut cookies and freshly brewed espresso rips the unsuspecting right out of the elevator, but it's the live music, film, spectacular student artwork and photography-or friends in side-that keeps students coming back to the new Myron Hokin Student Center. ((The center is new for Columbia and provides students with the opportunity to experience the diverse energies here. n Located on the first floor of Columbia's Wabash Avenue campus, the new center was underwritten by Columbia Board Trustee Myron Hokin. Since it opened this fall, the center has been buzzing with activity, Lively and inviting, the new Myron Hokin Student Center is a very popular spot. and a quick peek inside at any time during the day shows clearly how welcome it is! "When I was in grad school here, there was no place to get together," says readings; an Australian musical group; student musical groups; and a saree center director and 1986 Interdisciplinary Arts Education grad Bobbie Stuart. -

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 435 282 HE 032 500 TITLE Illinois Directory of Higher Education, 1999. INSTITUTION Illinois State Board of Higher Education, Springfield. PUB DATE 1999-10-00 NOTE 48p. AVAILABLE FROM State of Illinois Board of Higher Education, 431 EastAdams, Second Floor, Springfield, IL 62701-1418. Tel: 217-782-2551; Fax: 217-782-8548; Web site: <http://www.ibhe.state.il.us>. PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Directories/Catalogs (132) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Agencies; Boards of Education; Community Colleges; Higher Education; Organizations (Groups); *Private Colleges; Proprietary Schools; *Public Colleges; State Universities IDENTIFIERS *Illinois ABSTRACT This directory of higher education in Illinois includes information on the Illinois Board of Higher Education, state publiccolleges and universities, independent institutions, and other stateagencies and educational organizations. The section on the Illinois Board ofHigher Education lists board members and staff, and includes an organizationchart. The section on public institutions lists board members andkey executives for the state's nine state universities, the Illinois CommunityCollege Board, and each of the state's community colleges. The section onindependent institutions provides the names, addresses, and presidents ofnot-for-profit colleges and universities and for-profit institutions. The section onother state agencies and educational organizations provides contactinformation and lists key personnel of eight other state agencies and educational organizations, including the State Board of Education, the Illinois Student Assistance Commission, and the State Universities Civil Service System.The directory concludes with maps keyed to indicate the geographic locationof both public and independent institutions in the state.(DB) Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. -

2019–20 Student Handbook Phd Program Contents Click on a Section to Navigate

2019–20 Student Handbook PhD Program Contents Click on a section to navigate. Academic calendar 2019–20 2 Registration/student records policies and procedures 33 Welcome to Erikson Institute 3 Academic records 33 Add/drop procedures 33 Our mission and values 4 Audited courses 33 Admission requirements 6 Change of address 34 Change of name 34 Degree requirements 8 Extension of time 34 Holds on registration 35 PhD course descriptions 12 Immunization records 35 Incomplete policy 35 Academic policies and procedures 14 Independent study 36 Academic integrity 14 Leave of absence 36 Academic grievance procedure 16 Official communications 37 Attendance and classroom decorum 17 Preferred/chosen name 37 Conferral of degrees at Loyola 18 Readmission 38 Copyright protection for work created by others 18 Registration 38 Copyright protection for work created by students 18 Repeated courses 38 Course and end-of-year evaluations 19 Review of records — Erikson Institute 38 Credit hour policy at Erikson 19 Review of records — Loyola University Chicago 40 English-language requirement 20 Transcript requests 42 Final examinations 21 Transfer credit 42 Freedom of inquiry 21 Withdrawing from the doctoral program 43 Good academic standing 21 Grading system at Loyola 21 Erikson student rights and responsibilities 44 Internships 21 General 44 Probation 22 Finance 44 Registration 44 Erikson campus policies and procedures 23 Student conduct 44 Building access information 23 Student disciplinary process 45 Concealed carry policy 23 Discrimination and harassment, including -

Course / Instructor(S)

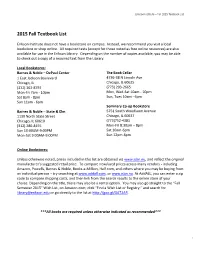

Erikson Institute – Fall 2015 Textbook List 2015 Fall Textbook List Erikson Institute does not have a bookstore on campus. Instead, we recommend you visit a local bookstore or shop online. All required texts (except for those noted as free online resources) are also available for use in the Erikson Library. Depending on the number of copies available, you may be able to check out a copy of a required text from the Library. Local Bookstores: Barnes & Noble – DePaul Center The Book Cellar 1 East Jackson Boulevard 4736-38 N Lincoln Ave Chicago, IL Chicago, IL 60625 (312) 362-8792 (773) 293-2665 Mon-Fri 7am - 10pm Mon, Wed-Sat 10am - 10pm Sat 8am - 8pm Sun, Tues 10am - 6pm Sun 11am - 6pm Seminary Co-op Bookstore Barnes & Noble – State & Elm 5751 South Woodlawn Avenue 1130 North State Street Chicago, IL 60637 Chicago, IL 60610 (773)752-4381 (312) 280-8155 Mon-Fri 8:30am – 8pm Sun 10:00AM-9:00PM Sat 10am-6pm Mon-Sat 9:00AM-9:00PM Sun 12pm-6pm Online Bookstores: Unless otherwise noted, prices included in this list are obtained via www.isbn.nu, and reflect the original manufacturer’s suggested retail price. To compare new/used prices across many vendors - including Amazon, Powells, Barnes & Noble, Books-a-Million, Half.com, and others where you may be buying from an individual person – try searching at www.addall.com, or www.isbn.nu. At AddALL, you can enter a zip code to compare shipping costs, and then link from the search results to the online store of your choice. -

On-Campus Master's Degree Programs 2017–18 Academic Year

On-Campus Master’s Degree Programs 2017–18 Academic Year Tracy Vega M.S.W., 2016 Caregiver Support Team Clinician Association House of Chicago Earning your master’s degree at Erikson Institute is the best preparation you can get for the career that lies ahead of you. The work you’ve chosen—ensuring that the children of today grow up to be the healthy, happy, responsible, and productive adults of tomorrow—is not easy, and it couldn’t be more important. You owe it to yourself to choose an education that’s equal to the task. An education that enables you to • Develop the skills to be a leader in a variety of social service and early childhood fields. • Gain a deep, research-based understanding of child development and family functioning. • Challenge yourself as you examine your knowledge, actions, and assumptions. • Join a close-knit community of professionals passionate about children and families, just like you are. • Have the greatest impact you can on the lives of the children and families you serve. An Erikson education is all of this and more. Brian Puerling M.S. in Early Childhood Education, 2011 Director of Education Technology Catherine Cook School, Chicago Learn how children develop and why it matters At Erikson, whether you choose our master’s degree program in child development, social work, or early childhood education, you’ll learn how children develop and the complex contextual factors that shape development. You’ll learn about specific developmental domains, including physical/motor, cognitive, social, emotional, and communicative/language, and how developmental processes weave these domains together.