Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charter Petition Review While Ensuring Ready Access to the DRL for Any Given Section of the Charter

PUC Triumph Charter Academy and PUC Triumph Charter High School A School of Partnerships to Uplift Communities (PUC) Valley Dr. Jacqueline Elliot Adriana Abich Partnerships to Uplift Communities (PUC) - Valley 1405 N. San Fernando Blvd. Suite 303 Burbank, CA 91502 818-559-7699 Voice 818-559-8641 Fax Submitted: September 14, 2015 PUC Triumph Charter Academy and PUC Triumph Charter High School Table of Contents ASSURANCES AND AFFIRMATION 4 ELEMENT 1 – THE EDUCATIONAL PROGRAM 6 GENERAL INFORMATION 6 1.1 COMMUNITY NEED FOR CHARTER SCHOOL 10 1.2 STUDENT POPULATION TO BE SERVED 32 1.3 Five Year Enrollment Plan 42 1.4 Surrounding Schools Demographic and Performance Data 43 1.5 VISION & MISSION 44 1.6 EDUCATED PERSON OF THE 21ST CENTURY 44 1.7 HOW LEARNING BEST OCCURS 46 1.8 HOW THE GOALS ENABLE SELF‐MOTIVATED, COMPETENT LIFE‐LONG LEARNERS 49 1.9 REQUIREMENTS OF CALIFORNIA EDUCATION CODE § 47605(B)(5)(A)(II) 52 1.10 INSTRUCTIONAL DESIGN 61 1.11 CURRICULUM 71 1.12 GRADUATION REQUIREMENTS 91 1.13 INSTRUCTIONAL METHODOLOGIES AND STRATEGIES 94 1.14 STUDENT MASTERY OF CA CCSS AND OTHER STATE CONTENT STANDARDS 96 1.15 DEVELOPMENT OF TECHNOLOGY‐RELATED SKILLS 100 1.16 ACADEMIC CALENDAR 102 1.17 DAILY SCHEDULES 103 1.18 INSTRUCTIONAL DAYS AND MINUTES 109 1.19 TEACHER RECRUITMENT 109 1.20 PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT 111 1.21 MEETING THE NEEDS OF ENGLISH LEARNERS 117 1.22 MEETING THE NEEDS OF GIFTED STUDENTS 122 1.23 MEETING THE NEEDS OF STUDENTS ACHIEVING BELOW GRADE LEVEL 124 1.24 MEETING THE NEEDS OF SOCIO‐ECONOMICALLY DISADVANTAGED STUDENTS 132 1.25 MEETING -

2020–21 Student Handbook MS Degree Programs Graduate Certificate Programs Students at Large Contents Click on a Section to Navigate

Graduate School in Child Development 2020–21 Student Handbook MS Degree Programs Graduate Certificate Programs Students at Large Contents Click on a section to navigate. Reservation of rights 2 Registration/student records policies and procedures 82 Coronavirus (COVID-19) 3 Academic records 82 Add/drop procedures 82 Academic calendar 2020–21 4 Audited courses 82 Welcome to Erikson Institute 6 Change of address 82 Changing programs 83 Our mission and values 7 Course substitution 83 Holds on registration 83 Admission requirements 9 Immunization records 83 Incomplete policy 84 Master’s degree programs 11 Independent study 84 Leave of absence 85 Master’s degree course descriptions 31 Official Institute communications 85 Preferred-chosen name 86 Graduate certificate programs 51 Readmission 86 Registration 86 Certificate program course descriptions 56 Repeated courses 86 Academic policies and procedures 61 Review of records 86 Transcript requests 88 Academic integrity 61 Transfer credit 88 Academic grievance procedure 63 Withdrawing from Erikson 89 Academic probation and warning: continuing students 64 Academic probation: exiting academic probation 65 Student rights and responsibilities 90 Attendance policy and classroom decorum 65 General 90 Comprehensive examination 66 Finance 90 Conditional admission: new students 67 Registration 90 Conferral of degrees and certificates 67 Student conduct 91 Continuous enrollment policy 67 Student disciplinary process 91 Copyright protection for work created by others 68 Technical standards 93 Copyright protection -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93493042019134 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947 (a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code ( except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2012 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Service 1-The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements A For the 2012 calendar year, or tax year beginning 07-01-2012 , 2012, and ending 06-30-2013 C Name of organization B Check if applicable D Employer identification number PEER HEALTH EXCHANGE INC F Address change 56-2374305 Doing Business As F Name change fl Initial return Number and street (or P 0 box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite E Telephone number 70 GOLD STREET p Terminated (415)684-1230 (- Amended return City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 SAN FRANCISCO, CA 94133 I Application pending G Gross receipts $ 8,773,516 F Name and address of principal officer H(a) Is this a group return for LOUISE D LANGHEIER affiliates? (-Yes No 70 GOLD STREET SAN FRANCISCO,CA 94133 H(b) Are all affiliates included? F Yes F_ No If "No," attach a list (see instructions) I Tax-exempt status F 501(c)(3) 1 501(c) ( ) I (insert no ) (- 4947(a)(1) or F_ 527 H(c) Group exemption number - J Website :1- WWW PEERHEALTHEXCHANGE ORG K Form of organization F Corporation 1 Trust F_ Association (- Other 0- L Year of formation 2003 M State of legal domicile NY Summary 1 Briefly describe the organization's mission or most significant activities TO GIVE TEENAGERS THE KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS THEY NEED TO MAKE HEALTHY DECISIONS w 2 Check this box if the organization discontinued its operations or disposed of more than 25% of its net assets 3 Number of voting members of the governing body (Part VI, line 1a) . -

The Blue and White

THE UNDERGRADUATE MAGAZINE OF COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY, EST. 1890 THE BLUE AND WHITE Vol. XIX No. III May 2013 Lies My Teacher Told Me What you need to know before you teach for America Paying it Forward Pervasive debt at Columbia's nontraditional college ALS O INSIDE: CULTURE! AND SUB-CULTURE! Conor Skelding, CC ’14, Editor in Chief ANNA BAHR, BC ’14, Managing Editor ALLIE CURRY, CC ’13, Senior Editor Will Holt, CC ’15, Senior Editor TORSTEN ODLAND, CC ’15, Senior Editor CLAIRE SABEL, CC ’13, Senior Editor JESSIE CHASAN-TABer, CC ’16, Layout Editor LEILA MGALOBLISHVILI, CC ’16, Senior Illustrator ZUZANA GIERTLOVA, BC ’14, Publisher SOMER OMAR, CC ’16, Public Editor Staff Writers NAOMI SHArp, CC ’15 ALEXANDER PINES, CC ’16 Contributors NAOMI COHen, CC ’15 KATIE DONAHoe, BC ’16 BRITT FOSSUM, CC ’16 LUCA MARZORAti, CC ’15 MATTHEW SCHANTZ, CC ’13 DANIEL STONE, CC ’16 ALEXANDRA SVOKOS, CC ’14 HALLIE NELL SWANSON, CC ’16 Artists JULIETTE CHEN, CC ’16 BRITT FOSSUM, CC ’16 JIYOON HAN, CC ’13 ANGEL JIANG, CC ’15 KATHARINE LIN, CC ’16 ELISA MIRKIL, CC ’16 ALEXANDER PINES, CC ’16 ANNE SCOTTI, CC ’16 HANK SHORB, CC ’16 Editors Emeriti SYLVIE KREKOW, BC ’13 BRIAN WAGNER, SEAS ’13 THE BLUE & WHITE Vol. XIX FAMAM EXTENDIMUS FACTIS No. III COLUMNS FEATURES 4 BLUEBOOK Sylvie Krekow & 10 AT TWO SWORDS’ LENGTH: SHOULD YOU GRADUATE? 6 BLUE NOTES Brian Wagner Our monthly prose and cons 8 CAMPUS CHARACTERS 12 VERILY VERITAS Will Holt 13 ALL BROOKLYN BEER TASTES THE SAME 27 CURIO COLUMBIANA A B&W editor hops to Brooklyn to see what’s brewing 28 SKETCHBOOK 34 MEASURE -

Chicago College of Performing Arts) Provided the Foundation for Successes I’Ve Enjoyed Both in Life and in Music

FALL 2005 REVIEW RA MAGAZINEO FOR ALUMNI AOND FRIENDS OF RSEVELTOOSEVELT UNIVERSITY Roosevelt’s World class iolinists V page 4 V& iolins AKING A DIFFERENCE M in the lives that follow “My education at Roosevelt’s Chicago Musical College (now The Music Conservatory of Chicago College of Performing Arts) provided the foundation for successes I’ve enjoyed both in life and in music. Because of my strong feelings for the mission of Roosevelt and in appreciation for the skills and musical inspiration I received, I wanted to remember the University.” Humbert “Bert” J. Lucarelli (BM ‘59) Humbert “Bert” J. Lucarelli has distinguished himself of Hartford in West Hartford, Conn, and the founder as one of America’s foremost musicians. He has been and president of Oboe International, Inc., a non-profit hailed as America’s leading oboe recitalist. Bert has foundation whose principal activity has been presenting performed extensively throughout the world with major the New York International Competition for solo oboists. symphony orchestras, and in 2002 he was the first Like many other Roosevelt University alumni, this American oboist to be invited to perform and teach at internationally renowned oboe recitalist has made the Central Conservatory in Beijing, China. Bert is a commitment to his alma mater in his estate plans. professor of oboe at the Hartt School at the University Fred Barney Planned and Major Gifts Office of Institutional Advancement U L T N E I Roosevelt University V V E E 430 S. Michigan Avenue, Rm. 827 R S S O Chicago, IL 60605 I T O Y Phone: (312) 341-6455 R 1 9 4 5 Fireside Circle Fax: (312) 341-6490 Toll-free: 1-888-RU ALUMS E-mail: [email protected] FALL 2005 REVIEW RRA MAGAZINEOO FOR ALUMNI AONDO FRIENDS OF RSSOOSEVELTEVEEVE UNIVERSITY LLTT FOCUS SNAPSHOTS VIOLIN VIRTUOSOS RU PARTNERS WITH SOCIAL TEACH & PERFORM ....................... -

December 2019 Higher Education Cohorts

December 2019 Higher Education Cohorts PD290© 2019 INCCRRA Cohort Pathways in Illinois: Innovative Models Supporting the Early Childhood Workforce Institutions of higher education in Illinois have long implemented collaborative, innovative strategies to support credential and degree attainment. The Illinois Governor’s Office of Early Childhood Development (GOECD) is invested in supporting flexible, responsive pathways to credentials and degree attainment for early childhood practitioners, as early childhood practitioners equipped with appropriate knowledge and skills are critical to developing and implementing high-quality early childhood experiences for young children and their families. At the same time, the State of Illinois is eager to ensure that pathways developed not only support entry into and progression within the field, but also are inclusive of and responsive to programs’ diverse and experienced staff members who have not yet attained new credentials and/or degrees. The purpose of this paper is to highlight the innovative work of Illinois institutions of higher education in creating cohort pathways that are responsive to the needs of the current and future early childhood workforce. Cohort models are commonly defined as a group of students moving through a program in a cohesive fashion with support provided for the overall healthy functioning of the group. In this paper, the highlighted cohort pathways focus on additional supports provided to cohort model participants (social and practical) as well as innovative model designs. Understanding these unique cohort pathways requires a fundamental understanding of existing credential and degree pathways in Illinois, the current early childhood education (ECE) workforce, present challenges in growing an ECE workforce, and research highlighting 1 innovative components of cohort models. -

March 3, 2017 the Honorable Donald J. Trump President of the United States of America the White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue

March 3, 2017 The Honorable Donald J. Trump President of the United States of America The White House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, NW Washington, DC 20500 Dear President Trump: On behalf of the more than 500 undersigned organizations, we are writing to warn of the dire consequences of repealing the Prevention and Public Health Fund (the Prevention Fund), authorized under the Affordable Care Act. Repealing the Prevention Fund without a corresponding increase in the allocation for the Labor-Health and Human Services-Education appropriations bill would leave a funding gap for essential public health programs, and could also foretell deep cuts for other critical programs funded in the bill. Today, more than 12 percent of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) budget is supplied through Prevention Fund investments. This includes core public health programs that provide essential funds to help states keep communities healthy and safe, such as the 317 immunization program, epidemiology and laboratory capacity grants, the entire Preventive Health and Health Services (Prevent) Block Grant program, cancer screenings, chronic disease prevention and other critically important programs. For example, the Prevent Block Grant provides all 50 states, the District of Columbia, two American Indian tribes, and eight U.S. territories with flexible funding to address their unique public health issues at the state and community level. Despite the growing and geographically disparate burden of largely preventable diseases, health threats such as the opioid epidemic, and emerging infectious disease outbreaks such as the Zika virus, federal disease prevention and public health programs remain critically underfunded. Public health spending is still below pre-recession levels, having remained relatively flat for years. -

Student, Family, and Staff Perspectives on a New School

RESEARCHARTICLE ‘‘Can’t We Just Have Some Sazon?’’´ Student, Family, and Staff Perspectives on a New School Food Program at a Boston High School a b c d e f AVIK CHATTERJEE, MD, MPH GENEVIEVE DAFTARY, MD, MPH MEG CAMPBELL,MA LENWARD GATISON,BA LIAM DAY,MA KIBRET RAMSEY, g h ROBERTA GOLDMAN, PhD, MA MATTHEW W. GILLMAN,MD,SM ABSTRACT BACKGROUND: In September 2013, a Massachusetts high school launched a nutrition program in line with 2013 United States Department of Agriculture requirements. We sought to understand attitudes of stakeholders toward the new program. METHODS: We employed community-based participatory research methods in a qualitative evaluation of the food program at the school, where 98% of students are students of color and 86% qualify for free/reduced lunch. We conducted 4 student (N = 32), 2 parent (N = 10), 1 faculty/staff focus group (N = 14), and interviews with school leadership (N = 3). RESULTS: A total of 10 themes emerged from focus groups and interviews, in 3 categories—impressions of the food (insufficient portion size, dislike of the taste, appreciation of the freshness, increased unhealthy food consumption outside school), impact on learning (learning what’s healthy, the program’s innovativeness, control versus choice), and concerns about stakeholder engagement (lack of student/family engagement, culturally incompatible foods). A representative comment was: ‘‘You need something to hold them from 9 to 5, because if they are hungry, McDonald’s is right there.’’ CONCLUSION: Stakeholders appreciated the educational value of the program but stakeholder dissatisfaction may jeopardize its success. Action steps could include incorporating culturally appropriate recipes in the school’s menus and working with local restaurants to promote healthier offerings. -

Peer Health Exchange -.Hub | Opportunities and Events from USC

Hey USC undergraduates! Are you someone who wants to get involved and… Loves working with youth and is looking for real classroom teaching experience? Is passionate about delivering presentations on health issues facing communities in Los Angeles? Seeks to be a part of the solution to health disparities? Peer Health Exchange (PHE) is looking for dedicated USC undergrads to teach health workshops in local public high schools. **apply today at www.peerhealthexchange.org/apply applications accepted on a rolling basis** Peer Health Exchange (PHE) is a non-profit organization that gives teenagers the knowledge and skills they need to make healthy decisions. We do this by training college students to teach a comprehensive health curriculum in public high schools that lack health education. This year, USC undergraduate volunteers will gain direct teaching experience in public high school classrooms by leading workshops about sexual health, relationships, communication, sexual violence, mental health and more. Join Peer Health Exchange TODAY to make a difference in the lives of Los Angeles teenagers! Apply NOW at www.peerhealthexchange.org/apply What will YOU do as a PHE volunteer? o Devote 4-6 hours a week for the entire 2012-2013 academic year to become a health workshop teacher in one of the following topics: · ● Sexual Decision-Making ● Tobacco · ● STIs & HIV ● Alcohol · ● Pregnancy Prevention ● Drugs · ● Healthy Relationships ● Nutrition & Physical Activity · ● Abusive Relationships ● Mental Health · ● Rape and Sexual Assault Attend the -

Entire Issue (PDF)

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 114 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 162 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, DECEMBER 5, 2016 No. 174 House of Representatives The House met at noon and was sion III football player of the year. Car- tral Minnesota Builders Association, called to order by the Speaker pro tem- ter Hanson has started every season for working to represent his and other pore (Mr. DENHAM). 4 years, was a preseason All-American, companies throughout the St. Cloud f and this year led his team in tackles. community and our State. Carter doesn’t just excel on the foot- Mike always goes above and beyond DESIGNATION OF SPEAKER PRO ball field, but in the classroom and the by hosting job site tours, advocating TEMPORE community as well. He has maintained for the building industry at the State The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- a 4.0 grade point average for 4 years, capitol, as well as educating elected of- fore the House the following commu- and this year, he has been selected as ficials on the issues and concerns of his nication from the Speaker: the only Division III finalist for the field. He even recently represented his WASHINGTON, DC, National Football Foundation’s Camp- company and industry at a roundtable December 5, 2016. bell Trophy, which is given to the best we hosted to explain their concerns I hereby appoint the Honorable JEFF student athlete in football. about our Nation’s failing healthcare DENHAM to act as Speaker pro tempore on Carter is a global business leadership system. -

2019–20 Student Handbook Phd Program Contents Click on a Section to Navigate

2019–20 Student Handbook PhD Program Contents Click on a section to navigate. Academic calendar 2019–20 2 Registration/student records policies and procedures 33 Welcome to Erikson Institute 3 Academic records 33 Add/drop procedures 33 Our mission and values 4 Audited courses 33 Admission requirements 6 Change of address 34 Change of name 34 Degree requirements 8 Extension of time 34 Holds on registration 35 PhD course descriptions 12 Immunization records 35 Incomplete policy 35 Academic policies and procedures 14 Independent study 36 Academic integrity 14 Leave of absence 36 Academic grievance procedure 16 Official communications 37 Attendance and classroom decorum 17 Preferred/chosen name 37 Conferral of degrees at Loyola 18 Readmission 38 Copyright protection for work created by others 18 Registration 38 Copyright protection for work created by students 18 Repeated courses 38 Course and end-of-year evaluations 19 Review of records — Erikson Institute 38 Credit hour policy at Erikson 19 Review of records — Loyola University Chicago 40 English-language requirement 20 Transcript requests 42 Final examinations 21 Transfer credit 42 Freedom of inquiry 21 Withdrawing from the doctoral program 43 Good academic standing 21 Grading system at Loyola 21 Erikson student rights and responsibilities 44 Internships 21 General 44 Probation 22 Finance 44 Registration 44 Erikson campus policies and procedures 23 Student conduct 44 Building access information 23 Student disciplinary process 45 Concealed carry policy 23 Discrimination and harassment, including -

Course / Instructor(S)

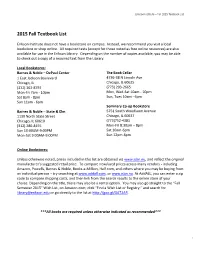

Erikson Institute – Fall 2015 Textbook List 2015 Fall Textbook List Erikson Institute does not have a bookstore on campus. Instead, we recommend you visit a local bookstore or shop online. All required texts (except for those noted as free online resources) are also available for use in the Erikson Library. Depending on the number of copies available, you may be able to check out a copy of a required text from the Library. Local Bookstores: Barnes & Noble – DePaul Center The Book Cellar 1 East Jackson Boulevard 4736-38 N Lincoln Ave Chicago, IL Chicago, IL 60625 (312) 362-8792 (773) 293-2665 Mon-Fri 7am - 10pm Mon, Wed-Sat 10am - 10pm Sat 8am - 8pm Sun, Tues 10am - 6pm Sun 11am - 6pm Seminary Co-op Bookstore Barnes & Noble – State & Elm 5751 South Woodlawn Avenue 1130 North State Street Chicago, IL 60637 Chicago, IL 60610 (773)752-4381 (312) 280-8155 Mon-Fri 8:30am – 8pm Sun 10:00AM-9:00PM Sat 10am-6pm Mon-Sat 9:00AM-9:00PM Sun 12pm-6pm Online Bookstores: Unless otherwise noted, prices included in this list are obtained via www.isbn.nu, and reflect the original manufacturer’s suggested retail price. To compare new/used prices across many vendors - including Amazon, Powells, Barnes & Noble, Books-a-Million, Half.com, and others where you may be buying from an individual person – try searching at www.addall.com, or www.isbn.nu. At AddALL, you can enter a zip code to compare shipping costs, and then link from the search results to the online store of your choice.