Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020–21 Student Handbook MS Degree Programs Graduate Certificate Programs Students at Large Contents Click on a Section to Navigate

Graduate School in Child Development 2020–21 Student Handbook MS Degree Programs Graduate Certificate Programs Students at Large Contents Click on a section to navigate. Reservation of rights 2 Registration/student records policies and procedures 82 Coronavirus (COVID-19) 3 Academic records 82 Add/drop procedures 82 Academic calendar 2020–21 4 Audited courses 82 Welcome to Erikson Institute 6 Change of address 82 Changing programs 83 Our mission and values 7 Course substitution 83 Holds on registration 83 Admission requirements 9 Immunization records 83 Incomplete policy 84 Master’s degree programs 11 Independent study 84 Leave of absence 85 Master’s degree course descriptions 31 Official Institute communications 85 Preferred-chosen name 86 Graduate certificate programs 51 Readmission 86 Registration 86 Certificate program course descriptions 56 Repeated courses 86 Academic policies and procedures 61 Review of records 86 Transcript requests 88 Academic integrity 61 Transfer credit 88 Academic grievance procedure 63 Withdrawing from Erikson 89 Academic probation and warning: continuing students 64 Academic probation: exiting academic probation 65 Student rights and responsibilities 90 Attendance policy and classroom decorum 65 General 90 Comprehensive examination 66 Finance 90 Conditional admission: new students 67 Registration 90 Conferral of degrees and certificates 67 Student conduct 91 Continuous enrollment policy 67 Student disciplinary process 91 Copyright protection for work created by others 68 Technical standards 93 Copyright protection -

Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows Program

Barbara Cohort Bowman Leadership 2017 Fellows The Early Childhood Leadership Academy is pleased to present the policy memos developed by the 2017 Policy Cohort of the Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows Program. Memos SPECIAL ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Support The Early Childhood Leadership Academy at Erikson Institute gratefully acknowledges the support and generosity of The Irving B. Harris Foundation for its support of the Barbara Bowman Leadership Fellows program. BARBARA BOWMAN We are honored to have the program named after one of Erikson Institute’s founders, Barbara Taylor Bowman. Barbara’s legacy as an education activist, policy adviser, and early childhood practitioner matches the characteristics of the fellows this program aims to attract. Furthermore, her dedication to ensuring that diversity and equity are mutually reinforced provides the framework that supports the entire program experience. This effort draws from Erikson’s mission-driven work to ensure a future in which all children have equitable opportunities to realize their full potential through leadership and policy influence. Special thanks to President and CEO, Geoffrey A. Nagle for his continuous commitment to the program. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Participating Organizations TABLE OF CONTENTS ACCESS ..........................................................................................................1 CARISA HURLEY ...................................................................................................... 1 CINDY LA .............................................................................................................. -

Chicago College of Performing Arts) Provided the Foundation for Successes I’Ve Enjoyed Both in Life and in Music

FALL 2005 REVIEW RA MAGAZINEO FOR ALUMNI AOND FRIENDS OF RSEVELTOOSEVELT UNIVERSITY Roosevelt’s World class iolinists V page 4 V& iolins AKING A DIFFERENCE M in the lives that follow “My education at Roosevelt’s Chicago Musical College (now The Music Conservatory of Chicago College of Performing Arts) provided the foundation for successes I’ve enjoyed both in life and in music. Because of my strong feelings for the mission of Roosevelt and in appreciation for the skills and musical inspiration I received, I wanted to remember the University.” Humbert “Bert” J. Lucarelli (BM ‘59) Humbert “Bert” J. Lucarelli has distinguished himself of Hartford in West Hartford, Conn, and the founder as one of America’s foremost musicians. He has been and president of Oboe International, Inc., a non-profit hailed as America’s leading oboe recitalist. Bert has foundation whose principal activity has been presenting performed extensively throughout the world with major the New York International Competition for solo oboists. symphony orchestras, and in 2002 he was the first Like many other Roosevelt University alumni, this American oboist to be invited to perform and teach at internationally renowned oboe recitalist has made the Central Conservatory in Beijing, China. Bert is a commitment to his alma mater in his estate plans. professor of oboe at the Hartt School at the University Fred Barney Planned and Major Gifts Office of Institutional Advancement U L T N E I Roosevelt University V V E E 430 S. Michigan Avenue, Rm. 827 R S S O Chicago, IL 60605 I T O Y Phone: (312) 341-6455 R 1 9 4 5 Fireside Circle Fax: (312) 341-6490 Toll-free: 1-888-RU ALUMS E-mail: [email protected] FALL 2005 REVIEW RRA MAGAZINEOO FOR ALUMNI AONDO FRIENDS OF RSSOOSEVELTEVEEVE UNIVERSITY LLTT FOCUS SNAPSHOTS VIOLIN VIRTUOSOS RU PARTNERS WITH SOCIAL TEACH & PERFORM ....................... -

December 2019 Higher Education Cohorts

December 2019 Higher Education Cohorts PD290© 2019 INCCRRA Cohort Pathways in Illinois: Innovative Models Supporting the Early Childhood Workforce Institutions of higher education in Illinois have long implemented collaborative, innovative strategies to support credential and degree attainment. The Illinois Governor’s Office of Early Childhood Development (GOECD) is invested in supporting flexible, responsive pathways to credentials and degree attainment for early childhood practitioners, as early childhood practitioners equipped with appropriate knowledge and skills are critical to developing and implementing high-quality early childhood experiences for young children and their families. At the same time, the State of Illinois is eager to ensure that pathways developed not only support entry into and progression within the field, but also are inclusive of and responsive to programs’ diverse and experienced staff members who have not yet attained new credentials and/or degrees. The purpose of this paper is to highlight the innovative work of Illinois institutions of higher education in creating cohort pathways that are responsive to the needs of the current and future early childhood workforce. Cohort models are commonly defined as a group of students moving through a program in a cohesive fashion with support provided for the overall healthy functioning of the group. In this paper, the highlighted cohort pathways focus on additional supports provided to cohort model participants (social and practical) as well as innovative model designs. Understanding these unique cohort pathways requires a fundamental understanding of existing credential and degree pathways in Illinois, the current early childhood education (ECE) workforce, present challenges in growing an ECE workforce, and research highlighting 1 innovative components of cohort models. -

2019–20 Student Handbook Phd Program Contents Click on a Section to Navigate

2019–20 Student Handbook PhD Program Contents Click on a section to navigate. Academic calendar 2019–20 2 Registration/student records policies and procedures 33 Welcome to Erikson Institute 3 Academic records 33 Add/drop procedures 33 Our mission and values 4 Audited courses 33 Admission requirements 6 Change of address 34 Change of name 34 Degree requirements 8 Extension of time 34 Holds on registration 35 PhD course descriptions 12 Immunization records 35 Incomplete policy 35 Academic policies and procedures 14 Independent study 36 Academic integrity 14 Leave of absence 36 Academic grievance procedure 16 Official communications 37 Attendance and classroom decorum 17 Preferred/chosen name 37 Conferral of degrees at Loyola 18 Readmission 38 Copyright protection for work created by others 18 Registration 38 Copyright protection for work created by students 18 Repeated courses 38 Course and end-of-year evaluations 19 Review of records — Erikson Institute 38 Credit hour policy at Erikson 19 Review of records — Loyola University Chicago 40 English-language requirement 20 Transcript requests 42 Final examinations 21 Transfer credit 42 Freedom of inquiry 21 Withdrawing from the doctoral program 43 Good academic standing 21 Grading system at Loyola 21 Erikson student rights and responsibilities 44 Internships 21 General 44 Probation 22 Finance 44 Registration 44 Erikson campus policies and procedures 23 Student conduct 44 Building access information 23 Student disciplinary process 45 Concealed carry policy 23 Discrimination and harassment, including -

Course / Instructor(S)

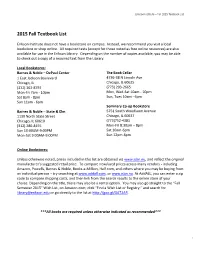

Erikson Institute – Fall 2015 Textbook List 2015 Fall Textbook List Erikson Institute does not have a bookstore on campus. Instead, we recommend you visit a local bookstore or shop online. All required texts (except for those noted as free online resources) are also available for use in the Erikson Library. Depending on the number of copies available, you may be able to check out a copy of a required text from the Library. Local Bookstores: Barnes & Noble – DePaul Center The Book Cellar 1 East Jackson Boulevard 4736-38 N Lincoln Ave Chicago, IL Chicago, IL 60625 (312) 362-8792 (773) 293-2665 Mon-Fri 7am - 10pm Mon, Wed-Sat 10am - 10pm Sat 8am - 8pm Sun, Tues 10am - 6pm Sun 11am - 6pm Seminary Co-op Bookstore Barnes & Noble – State & Elm 5751 South Woodlawn Avenue 1130 North State Street Chicago, IL 60637 Chicago, IL 60610 (773)752-4381 (312) 280-8155 Mon-Fri 8:30am – 8pm Sun 10:00AM-9:00PM Sat 10am-6pm Mon-Sat 9:00AM-9:00PM Sun 12pm-6pm Online Bookstores: Unless otherwise noted, prices included in this list are obtained via www.isbn.nu, and reflect the original manufacturer’s suggested retail price. To compare new/used prices across many vendors - including Amazon, Powells, Barnes & Noble, Books-a-Million, Half.com, and others where you may be buying from an individual person – try searching at www.addall.com, or www.isbn.nu. At AddALL, you can enter a zip code to compare shipping costs, and then link from the search results to the online store of your choice. -

On-Campus Master's Degree Programs 2017–18 Academic Year

On-Campus Master’s Degree Programs 2017–18 Academic Year Tracy Vega M.S.W., 2016 Caregiver Support Team Clinician Association House of Chicago Earning your master’s degree at Erikson Institute is the best preparation you can get for the career that lies ahead of you. The work you’ve chosen—ensuring that the children of today grow up to be the healthy, happy, responsible, and productive adults of tomorrow—is not easy, and it couldn’t be more important. You owe it to yourself to choose an education that’s equal to the task. An education that enables you to • Develop the skills to be a leader in a variety of social service and early childhood fields. • Gain a deep, research-based understanding of child development and family functioning. • Challenge yourself as you examine your knowledge, actions, and assumptions. • Join a close-knit community of professionals passionate about children and families, just like you are. • Have the greatest impact you can on the lives of the children and families you serve. An Erikson education is all of this and more. Brian Puerling M.S. in Early Childhood Education, 2011 Director of Education Technology Catherine Cook School, Chicago Learn how children develop and why it matters At Erikson, whether you choose our master’s degree program in child development, social work, or early childhood education, you’ll learn how children develop and the complex contextual factors that shape development. You’ll learn about specific developmental domains, including physical/motor, cognitive, social, emotional, and communicative/language, and how developmental processes weave these domains together. -

Subsequent College Enrollment After Graduation Traditional Undergraduate Degree Recipients

Dominican University Undergraduate Degree Program Completers AY2009 - AY2018 Subsequent College Enrollment After Graduation Subsequent College Enrollment of Traditional* Undergraduate Program Completers Year No Subsequent Graduated 2-Year Institution 4-Year Institution Enrollment on Record Grand Total AY0809 32 12.4% 107 41.5% 119 46.1% 258 100.0% AY0910 33 9.3% 154 43.5% 167 47.2% 354 100.0% AY1011 29 8.2% 145 41.1% 179 50.7% 353 100.0% AY1112 32 9.2% 121 34.9% 194 55.9% 347 100.0% AY1213 34 8.2% 159 38.1% 224 53.7% 417 100.0% AY1314 32 8.0% 154 38.5% 214 53.5% 400 100.0% AY1415 36 9.0% 135 33.8% 228 57.1% 399 100.0% AY1516 29 7.2% 141 35.0% 233 57.8% 403 100.0% AY1617 30 5.8% 128 25.0% 355 69.2% 513 100.0% AY1718 18 3.4% 92 17.6% 413 79.0% 523 100.0% Subsequent College Enrollment After Graduation Traditional Undergraduate Degree Recipients 100% 90% 80% 46.1% 53.7% 70% 69.2% 60% 79.0% 50% 40% 41.5% 30% 38.1% 20% 25.0% 10% 17.6% 12.4% 8.2% 5.8% 0% 3.4% Class of 2009 Class of 2013- Class of 2017 - Class of 2018 - After 10 Years After 5 Years After 1 Year Fall term after 2-Yr 4-Yr None * Exludes CASS program completers. Source: Student Tracker, National Student Loan Clearinghouse Prepared by the Office of Institutional Effectiveness, January 7, 2019 Dominican University Undergraduate Program Completers AY2009 -AY2018 Subsequent College Enrollment After Graduation College 2-year / Public / Subsequent College: State 4-year Private Count Percent DOMINICAN UNIVERSITY IL 4 Private 323 8.1% TRITON COLLEGE IL 2 Public 92 2.3% DEPAUL UNIVERSITY -

TARGETING TRAUMA Roosevelt Neuropsychologist Develops field Test to See Page 59 for a Baseball Season Measure a Soldier’S Readiness to Return to Battle

NONPROFIT U.S. POSTAGE PAID 430 S. Michigan Ave. ROOSEVELT Chicago, IL 60605-1394 UNIVERSITY Address Service Requested Become a fan at: Facebook.com/RooseveltUniversity TARGETING TRAUMA Roosevelt neuropsychologist develops field test to See page 59 for a baseball season measure a soldier’s readiness to return to battle. schedule, and visit rooseveltlakers.com for the latest news, scores and highlights! ROOSEVELT REVIEW | SPRING2011 CONTENTS HE TRAVELED THE WORLD, BUT NEVER FORGOT ROOSEVELT UNIVERSITY HAROLD S. ALEXANDER | 1938-2008 Roosevelt University is pleased to announce that it has received an $87,000 gift from the estate of alumnus Harold S. Alexander. Alexander began his career as a supervisor for the Internal Revenue Service in Chicago after receiving two business degrees from Roosevelt, a bachelor’s in 1960 and a master’s in 1964. However, he never felt challenged or fulfilled in that job. In what would become a fortunate career change, Alexander transferred to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) as a senior systems analyst, where he thrived. His fascinat- ing career would last 33 years and enable him to travel the globe. The FAA sent him to installations in the United States, Europe and South America. He even spent one Thanksgiv- ing Day in Russia. Although he loved his home in Arlington, Va., Alexander retired to Siesta Key, Fla., where he was an active retiree, volunteering for the Community AIDS Network. He spent hours counseling patients and assisted in the daily admin- istrative tasks of the office. He also supported the Arthritis Foundation, the Eye Clinic and, because of his love for the elephants of Thailand, he contributed to many humane societies throughout the world. -

Matthew A. Shirrell

Matthew A. Shirrell School of Education and Social Policy Northwestern University 2120 Campus Drive Evanston, IL 60208 Phone: 847-467-2820 www.matthewshirrell.com [email protected] Education 2014 Ph.D., Human Development and Social Policy, Northwestern University Dissertation title: School working conditions and teacher attrition: The roles of policy, teacher preparation, and school principals Committee: David N. Figlio (chair), C. Kirabo Jackson, James P. Spillane 2007 M.S., Early Childhood Education, Erikson Institute 1998 B.A. (with Honors), English, Grinnell College Appointments 2014- Postdoctoral Fellow, Distributed Leadership Study, School of Education and Social Policy, Northwestern University Publications Shirrell, M. (in press). New principals, accountability, and commitment in low-performing schools. Journal of Educational Administration. Spillane, J. P., Shirrell, M., & Hopkins, M. (in press). Designing and deploying a Professional Learning Community (PLC) organizational routine: Bureaucratic and collegial structures in tandem. Les Dossiers des Sciences de l’Education. Revise and Resubmit Shirrell, M. (resubmitted). The effects of subgroup-specific accountability on teacher turnover and attrition. Education Finance and Policy. Manuscripts In Preparation Spillane, J. P. & Shirrell, M. (in preparation). Location, location: Physical proximity and teachers’ instructional advice and information networks. Spillane, J. P. & Shirrell, M. (in preparation). What predicts the dissolution of instructional advice and information ties between teachers? Bristol, T. & Shirrell, M. (in preparation). The instructional advice and information networks of African American and Hispanic teachers. Spillane, J. P., & Shirrell, M. (in preparation). Engaging the “black box” of teacher peer effects: Do teachers seek out higher-performing peers for advice and information about teaching? Shirrell CV 1 Shirrell, M. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE GILLIAN DOWLEY McNAMEE Professor Director of Teacher Education Erikson Institute A Graduate School In Child Development 451 North LaSalle Street Chicago, Illinois 60654 (312) 755-2250 EDUCATION 1980 Ph.D. in Education, Reading and Language Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois 1976 Masters in the Science of Teaching University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 1974 – 1977 Three years of graduate study in Education Psychology University of Chicago, Chicago, Illinois 1974 B.A., Culture and Cognition Hampshire College, Amherst, Massachusetts PROFESSIONAL HISTORY 1992 – Present Professor, Director of Teacher Education, Erikson Institute 1987 -92 Associate Professor, Erikson Institute 1979-87 Assistant Professor, Erikson Institute 1981-85 Assistant Professorial Lecturer, Saint Xavier College, Chicago, IL 1980-81 Evaluation Consultant, Museum of Science and Industry, Chicago, IL 1979 Research Consultant, Threshold's Mother's Project, Chicago, IL 1977-80 Research Assistant, Center for Psychosocial Studies, Chicago, IL 1977-79 Substitute teacher, University of Chicago, Laboratory Schools, Chicago, IL 1975-77 Assistant kindergarten teacher, University of Chicago Laboratory Schools, Chicago, IL 1975 Kindergarten teacher, Hyde Park Jewish Community Center, Chicago, IL 1974-75 Preschool language arts teacher, Hyde Park Neighborhood Club, Chicago, IL 1973-74 Research Assistant, Rockefeller University, New York, NY 1972 Field study of kibbutz child-rearing, Kfar Blum, Upper Galilee, Israel 1971 - 72 Fifth grade science assistant teacher, Holyoke Public Schools, Holyoke, MA Gymnastic teacher and tutor in reading and math for 3rd graders, Holyoke, MA 1970 Assistant third grade teacher, Crocker Farm Elementary School, Amherst, MA HONORS AND AWARDS • Fellowship from the University of Chicago Trustees' Unendowed Funds for three years of graduate study in Educational Psychology, 1974-1977. -

ISBE Letterhead Template

MEMORANDUM TO: The Honorable Dan Mc Conchie, Senate Minority Leader The Honorable Don Harmon, Senate President The Honorable Jim Durkin, House Minority Leader The Honorable Chris Welch, Speaker of the House The Honorable JB Pritzker, Governor FROM: Dr. Carmen I. Ayala State Superintendent of Education DATE: August 27, 2021 SUBJECT: Illinois Educator Preparation Tests and Pass Rates Please find attached the Illinois educator preparation content tests and pass rates submitted in compliance with Illinois School Code, 105 ILCS 5/2-3.11d. This report lists all educator preparation providers in the state and the number of licensure content tests taken and passed by candidates at each institution from August 2020-August 2021. This report is a partial report (rather than three years of data) so the agency will be back on course for submission of the 3- year reports in 2024. A report covering August 2017-July 2020 was submitted September 2020. Note that the Test of Academic Proficiency (TAP) exam is not included in this report; this test was eliminated as a licensure requirement in August 2019. If you have any questions regarding this report, please contact Amanda Elliott, executive director of Legislative Affairs, at (217) 782-6510. cc: Secretary of the Senate Clerk of the House Legislative Research Unit State Government Report Center Pursuant to Illinois Administrative Code, 105 ILCS 5/2-3.11d, the report below details Illinois Educator Preparation Providers and content test data. Specific content test data broken down by institution of higher education follows. Community colleges, in addition to Illinois approved educator preparation providers, are included in the data.