Milan (1888-2000)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Lambro River Valley Greenways System Alessandro Toccolini∗, Natalia Fumagalli, Giulio Senes

Landscape and Urban Planning 76 (2006) 98–111 Greenways planning in Italy: the Lambro River Valley Greenways System Alessandro Toccolini∗, Natalia Fumagalli, Giulio Senes Institute of Agricultural Engineering, University of Milan, Via Celoria 2, 20133 Milano, Italy Available online 11 November 2004 Abstract The greenways movement in Europe developed differently to its counterpart in the USA, influenced by geographical, economic and cultural differences as well as differences in social and urban development. Europe has seen a discontinuous and fragmented process, diversified in the various countries. The explosion of the greenway concept in Europe is a very recent phenomenon: the European Greenways Association and the Italian Greenways Association both date back only as far as 1998. Clearly, before this date the European countries did see a degree of activity both cultural and operational, but it is equally clear that there was a lack of commonality. Specifically, greenway planning in Italy while on the one hand work has been underway on green trails for many years, on the other there is a clear lack of methodology that allows for the planning of a broader network. This paper has two objectives; firstly to define a methodology useful for greenways planning in Italy at regional level, and secondly, to demonstrate the application of this methodology to a case study. The methodology adopted derives from an approach to planning inspired principally by the work of Ian McHarg and Julius Fabos and already applied by the authors to protected areas in Italy. The methodology is structured in four phases: analysis of the landscape resources, the existing green trail and historical route networks; assessment of each element; composite assessment; and definition of the Greenways Plan. -

LE MEMORIE DI TRENNO. (Raccolte Da Silvano Acquani)

LE MEMORIE DI TRENNO. (raccolte da Silvano Acquani). In epoca romana era consuetudine dare agli agglomerati urbani, che si insediavano lungo le grandi arterie, che congiungevano tra loro centri di importanza strategica, commerciale e/o militare, una denominazione corrispondente alla loro distanza, misurata in miglia, dal “municipium” romano, nel nostro caso Mediolanum – Milano. La distanza incisa su cippi in sasso ( le pietre miliari ) è, quindi, testimonianza, sia della presenza dei romani, che di centri abitati. Nella cintura milanese questo fatto è testimoniato da un gran numero di “miliaria”. La grande arteria consolare, che da Mediolanum conduceva ad “Augusta Taurinorum” (Torino) e che oggi corrisponde grosso modo alla via Novara, rappresentava per i traffici romani una importante via di comunicazione. Su questa strada si trovavano Trenno (Trebennius = 3° miglio); Quarto (quarta lapide = 4° miglio); Quinto romano e Settimo milanese, che forse inizialmente erano solo insediamenti militari, stazioni di posta per il cambio di cavalli. Segmento della Tabula Peutingeriana con Mediolanum. CARTE E PERGAMENE TARDOMEDIOEVALI CHE MENZIONANO TRENNO. La prima memoria storica di Trenno porta la data del 17 marzo 877 e risulta in un rogito fra Leone e Sigifrido, preti officiali della chiesa di S. Ambrogio di Milano per un possesso “ in vico et fundo Triennum” nel villaggio e territorio di Trenno. Nel marzo 1017 i decumani, ufficiali e custodi della Basilica di S. Ambrogio, cedono ad Arivaldo di Baggio un campo nel luogo e fondo di Figino, di proprietà della Basilica, ricevendo in cambio un campo nel luogo e fondo di Trenno. Nelle coerenze del campo è nominata la “ chiesa di S. -

Malpensa Airport North Railway Link: Impact of Expected Traffic Onto the Existing Network

Malpensa Airport North Railway Link: impact of expected traffic onto the existing network Faculty of Civil and Industrial Engineering Department of Civil Constructional and Environmental Engineering Master Degree in Transport Systems Engineering Candidate: Filippo Zanzarin - 1746819 Supervisor Co-supervisor Prof. Stefano Ricci Ing. Emmanuele Vaghi A.A. 2017-2018 ABSTRACT This work presents an analysis about the performances of the lines and the nodes involved in the upgrade process of Malpensa International Airport accessibility. This study is developed throughout a new complete analysis model consisting of the rational integration of existing methods. The methodology proposed and applied for the evaluation of the railway infrastructural upgrade solutions for the development of the connections between Milan and its airport is conveniently developed and improved according to the study requirements. The evaluation of line and node capacity is carried out considering the actual and future layouts of the railway network at a regional level and the actual and planned services offered by the railway supplier. The results obtained recommend infrastructural upgrades in order to make available the matching network capacity. The analysis of the lines and the nodes involved in this process, as well as the effectiveness of the proposed infrastructural improvements, is strengthened by a scheduling analysis and the application of a simulation method. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .............................................................................................................................................. -

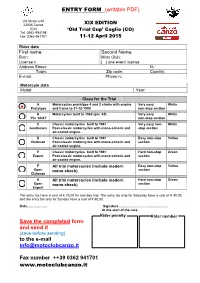

ENTRY FORM (Writable PDF) Save the Completed

ENTRY FORM (writable PDF) Via Meda n.40 22035 Canzo XIX EDITION (Co) ‘Old Trial Cup’ Caglio (CO) Tel. 0362-994198 Fax. 0362-941701 11-12 April 2015 Rider data First name: Second Name: Born: Moto Club: License n. [ ] one event license Address Street: N.: Town: Zip code: Country: E-mail: Phone n.: Motorcyle data Model: Year: Class for the Trial A Motorcycles prototype 4 and 2 stroke with engine Very easy White Prototype and frame to 31-12-1990 non-stop section B Motorcycles built to 1965 (pre ’65) Very easy White Pre ‘65/4T non-stop section C Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Ver y easy non - White Gentlemen Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and stop section air-cooled engine. D Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Easy non -stop Yellow Clubman Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and section air-cooled engine. E Classic motorcycles built to 1991 Hard non -stop Green Expert Post-classic motorcycles with mono-schock and section air-cooled engine. F All trial motorcycles (include modern Easy non -stop Yellow Open mono shock) section Clubman G All trial motorcycles (include modern Hard non -stop Green Open mono shock) section Expert The entry tax have a cost of € 75,00 for two day trial. The entry tax only for Saturday have a cost of € 40,00 and the entry tax only for Sunday have a cost of € 40,00. Data……………… Signature……………………………………… At the start of the race Rider penalty Rider number Save the completed form and send it (save before sending) to the e-mail [email protected] Fax number ++39 0362 941701 www.motoclubcanzo.it How reach the trial in Caglio (CO) From Turin : Highway Turin-Milan following on the west ring of Milan to direction Venice and exit to Cinisello Balsamo toward the highway Milan-Lecco direction Lecco. -

Lo Spazio Urbano Della Piazza D'armi Di Milano: Relazione Storica

Lo spazio urbano della Piazza d’Armi di Milano: relazione storica Dott. Giorgio Uberti1 Lo spazio urbano oggi occupato dalla Piazza d’Armi, dalla Caserma Santa Barbara e dall’Ospedale Militare di Milano si estende su una superficie che confina a nord con Via Novara e che comprende Via delle Forze Armate. Queste due strade, la cui esistenza è testimoniata da secoli, avvalorano la rilevanza storica dell’area in oggetto. 1. STORIA ANTICA Via Novara, sebbene disposta lungo un tracciato leggermente diverso da quello attuale, era ed è una delle più importanti strade di collegamento da e per la città, già utilizzata nell’età tardo-imperiale (III - IV secolo dopo Cristo) quando Milano, allora Mediolanum, era una delle due capitali dell’Impero Romano d’Occidente2. Si trattava della via Mediolanum – Novaria – Vercellae, grazie alla quale era possibile raggiungere Aosta, il passo del gran San Bernardo e la Gallia Transalpina3. Nella toponomastica di alcune vicine località milanesi è ancora possibile riconoscere il sistema miliare di questa strada: Quarto Cagnino, Quinto Romano e Settimo Milanese4. Via Forze Armate era una delle strade minori, dettagliatamente descritte all’interno degli Statuti delle strade e delle acque del contado di Milano5 del 1346. Anticamente era chiamata Strada de Bagio, dal nome di un villaggio distante circa sette chilometri dalle mura di Milano, già presente nel X secolo dopo Cristo6. Questa strada si distaccava dall’antica via per Novara presso l’attuale piazza De Angeli, località nella quale, ancora nella prima metà del XX secolo, era presente un ponte sul fiume Olona. È possibile ipotizzare che questa strada fosse già utilizzata in epoca tardo-imperiale per collegare Mediolanum con la località di Cesano Boscone, qui infatti sono stati effettuati svariati rinvenimenti archeologici in grado di dimostrare la presenza di un insediamento pagano del IV secolo dopo Cristo. -

Cycling Between Lodi and Milan 10 CYCLING ROUTES from PUNTO PARCO CASA DELL’ACQUA in PAULLO

Provincia Comune di Lodi di Paullo Cycling between Lodi and Milan 10 CYCLING ROUTES FROM PUNTO PARCO CASA DELL’ACQUA IN PAULLO > INTRODUCTION _ Translated by: Daniela Paraboschi PAULLO, LAND OF BOUNDARIES he history of Paullo is strongly con- nected to water. A vast water basin, the legendary and mysterious Lake Cycling between Lodi and Milan TGerundo, extended in the past from Truc- 10 CYCLING ROUTES FROM PUNTO PARCO CASA DELL’ACQUA IN PAULLO cazzano southwards, flooding most of that land that today is called the “Lodigiano” north from Lodi. Floods of the rivers Adda and Serio formed an area of morasses and marshes, and it is from the Latin word for marsh, “palus” (in Ital- ian “palude”) that the name Paullo is derived. The existence of Lake Gerundo is men- tioned in chronicles and documents until year 1000. Later on, the work of land recla- mation performed throughout Milanese and Lodigiano drained the lake away. Today the remains of this lake can be seen in Mignete (see Routes 1, 4 and 9) hamlet of Zelo Buon Persico, where a vast grove of reeds and wetlands (the famous “Mortone”) can be observed from the morphological terrace near the cycling route towards Lodi, along the Provincial Street SP16. Here it is common to see grey herons, pheasants and other rare birds that have found their ideal View of the Muzza towpath habitat in this environment. 1 Today the names of the places bring back to wetlands was reduced, merging the waters 1965 to make room for an ugly building in memory the legend of Lake Gerundo, with into the «Mutia» (ancient name of the Muzza reinforced concrete. -

Il Passante Ferroviario Trasporto Metropolitano E Regionale

Edited by Foxit PDF Editor Copyright (c) by Foxit Software Company, 2004 For Evaluation Only. L’Assessorato allo Sviluppo del Territorio del Comune di Milano ha aperto nel luglio 2001 il primo Urban Center d’Italia nel centro istituzionale e culturale della città. Urban Center ha l’obiettivo di comunicare ai cittadini le grandi trasformazioni del territorio, le politiche urbanistiche e le loro forme attuative. Si AIM rivolge ad un pubblico esteso, italiano ed internazionale, che comprende operatori Associazione economici di settore e non, studenti, turisti, amministratori pubblici, ai quali fornisce dati e informazioni sull’assetto territoriale della città, sulle sue potenzialità evolutive e Interessi Metropolitani sulle sue eccellenze. Urban Center è inoltre centro di dibattito e approfondimento per le tematiche che, sotto vari profili, riguardano il progetto di sviluppo urbano. Svolge la sua attività attraverso esposizione di progetti, conferenze e workshop negli spazi in Galleria Vittorio Emanuele, organizza itinerari di visita tematizzati, edizione di dossier e documenti illustrativi di progetti e temi urbanistici. Il programma d’iniziativa comunitaria Urban II Milano 2000- 2006 ha per obiettivo la riqualificazione della periferia nord-ovest di Milano. L’area d’intervento comprende i quartieri di Bovisa, Bovisasca, Certosa, Garegnano, Musocco, Quarto Oggiaro, Vialba e Villapizzone e riguarda una superficie di 12 kmq con una popolazione di 53.000 abitanti. Urban si propone di valorizzare le risorse ambientali, sociali ed economiche di questa zona sulla base di quattro grandi priorità strategiche: miglioramenti ecocompatibili dell'ambiente urbano; imprenditorialità e patti per l'occupazione volti a creare iniziative sociali; sistemi di trasporto intelligenti; gestione integrata e comunicazione. -

Aem Ing Sem Cop Ok

Half-yearly report at June 30, 2007 Contents The AEM Group at June 30, 2007 3 Key figures of the AEM Group 4 AEM on the Stock Exchange 6 Corporate bodies 8 Significant events during the period of the AEM Group 9 Directors’ report on operations 21 Summary of results, assets and liabilities and financial position of the AEM Group 22 Significant events after June 30, 2007 29 Outlook for operations 31 Condensed interim consolidated financial statements 33 Consolidated balance sheet 34 Consolidated income statement 36 Consolidated statement of cash flows 38 Statement of changes in Group consolidated shareholders’ equity 40 Consolidated Balance sheet pursuant to CONSOB Resolution no. 15519 of July 27, 2006 42 Consolidated Income statement pursuant to CONSOB Resolutio no. 15519 of July 27, 2006 44 General information 46 Changes in international accounting standards 48 Interpretation of IFRS and IFRIC not yet approved by the European Union 49 Scope of consolidation 50 Consolidation policies and procedures 53 Seasonal nature of the business 62 AEM Group - Areas of activity 63 Results sector by sector 64 Notes to the balance sheet items 66 Net financial debt 96 Notes to the statement of income items 97 Earnings per share 118 Notes on related party transactions 119 Consob communication no. DEM/6064293 of July 28, 2006 122 Guarantees and commitments with third parties 123 Other information 128 Half-yearly report at June 30, 2007 1 Contents Attachments to the notes to the consolidated interim financial statements 187 1. Statement of changes in property, plant and equipment 188 2. Statement of changes in intangible assets 190 3. -

Welcome to Milan

WELCOME TO MILAN WHAT MILAN IS ALL ABOUT MEGLIOMILANO MEGLIOMILANO The brochure WELCOME TO MILAN marks the attention paid to those who come to Milan either for business or for study. A fi rst welcome approach which helps to improve the image of the city perceived from outside and to describe the city in all its various aspects. The brochure takes the visitor to the historical, cultural and artistic heritage of the city and indicates the services and opportunities off ered in a vivid and dynamic context as is the case of Milan. MeglioMilano, which is deeply involved in the “hosting fi eld” as from its birth in 1987, off ers this brochure to the city and its visitors thanks to the attention and the contribution of important Institutions at a local level, but not only: Edison SpA, Expo CTS and Politecnico of Milan. The cooperation between the public and private sectors underlines the fact that the city is ever more aiming at off ering better and useable services in order to improve the quality of life in the city for its inhabitants and visitors. Wishing that WELCOME TO MILAN may be a good travel companion during your stay in Milan, I thank all the readers. Marco Bono Chairman This brochure has been prepared by MeglioMilano, a non-profi t- making association set up by Automobile Club Milan, Chamber of Commerce and the Union of Commerce, along with the Universities Bocconi, Cattolica, Politecnico, Statale, the scope being to improve the quality of life in the city. Milan Bicocca University, IULM University and companies of diff erent sectors have subsequently joined. -

Breve Storia Di Una Comunità Dalle Radici Profonde. Quarto Oggiaro È

Quarto Oggiaro: Breve storia di una Comunità dalle radici profonde. Quarto Oggiaro è un quartiere di Milano che porta con se ancora una cattiva nomea dagli anni ’80, dovuta al degrado e alle fragilità socio-economiche che hanno contraddistinto non solo la storia del dopoguerra del nostro quartiere ma l’intera narrazione delle periferie italiane. Molti conoscono la storia di Quarto come di un quartiere popolare sorto, a partire dal 1956, per accogliere la migrazione interna proveniente dal sud, impiantando palazzi di edilizia popolare su terreni che componevano la cintura agricola della città di Milano. Di fatto questa è la genesi del quartiere, come la conoscono tutti, pochi conoscono invece la fortissima identità storica di questo luogo e la sua strategica connessione con la città di Milano. In questo articolo proverò a tracciare il filo d’Arianna che unisce la storia del nostro quartiere con quella di Milano, della Lombardia e della penisola Italiana. Quarto Oggiaro è un toponimo abbastanza chiaro, con Quarto si indica le miglia romane dal centro città mentre si è poco discusso sul termine Oggiaro/Uglè/Uglerio così come è riportato dalle fonti storiche. Un analisi dei toponomi vicini a Quarto e della sua composizione ambientale ci proietta direttamente nel VI secolo A.C, quando secondo il cronista Romano Tito Livio, il principe celtico Belloveso a capo di una coalizione di popoli varca le Alpi, sconfigge gli Etruschi nella pianura Padana e fonda la sua città, su una collina che si ergeva su una vasta terra di paludi e acquitrini: la chiamerà Medh-lan , cioè “la terra sopra le acque” , che con il tempo prenderà il nome di Mesiolanum, Mediolanum e infine Milano. -

Il Futuro Della Valle Dei Monaci Allegato

Osservatorio per lo studio e la valorizzazione dei territori attraversati dai percorsi lenti Il futuro della Valle dei Monaci Proposte per l’Amministrazione Comunale di Milano e la Città Metropolitana milanese da parte delle Associazioni della Rete Valle dei Monaci Allegato “A” Relazione estesa Milano, luglio 2018 1 Il futuro della Valle dei Monaci: Proposte per l’Amministrazione comunale di Milano e la Città metropolitana milanese da parte delle Associazioni della Rete Valle dei Monaci. Premessa Questo documento vuole fornire alle Amministrazioni competenti e a tutti gli attori del territorio della Valle dei Monaci un supporto di analisi e di proposte per un possibile “Piano d’Area” orientato agli obiettivi di integrazione urbana, territoriale, sociale ed economica. Tali obiettivi sono già perseguiti nell’azione quotidiana degli attuali soggetti costituenti la Rete Valle dei Monaci, i quali ritengono che la loro quotidiana azione necessiti, a questo punto, anche di un impegno pubblico più deciso per questo territorio che, dopo lunghi decenni di indeterminazione e di degrado, ha cominciato a muoversi verso nuove e promettenti direzioni di sviluppo. Prima di dettagliare i temi ritenuti importanti per il Piano d’Area è però necessario trattare due punti prioritari: 1) spiegare che cos’è la Valle dei Monaci; 2) riportare, spiegandoli brevemente, i progetti pubblici e privati che già interessano il territorio del sud-Milano; ovverosia quelli che già intervengono direttamente sul destino della Valle dei Monaci e quelli di contesto urbano più ampio che sono destinati a influire sulle dinamiche locali. Il presente documento non ha pretese di essere esaustivo e può essere integrato in qualsiasi momento, sia da parte dei proponenti che da parte delle Amministrazioni, se queste lo riterranno una base utile per il loro lavoro. -

Schema Della Rete Metropolitana E Suburbana Dal 15 Luglio 2019 Metro and Suburban Lines As from 15 July 2019

Schema della rete Metropolitana e Suburbana dal 15 luglio 2019 Metro and Suburban lines as from 15 July 2019 S7 S8 Lecco Chiasso S11 Valmadrera S10 S40 Civate Sala al Barro Lecco Maggianico Como S. Giovanni Oggiono Molteno Calolziocorte Albate (Como Sud) Costa Masnaga S40 Cassago Airuno Cucciago Renate Mi8 S5 Varese Cantù Besana S2 Olgiate M. Mi7 Mariano Villa Raverio Gazzada Carimate Cabiate Carate-Calò Cernusco L. Orio al Serio Camnago Meda Castronno Triuggio Mi7 S4 Osnago Seveso Macherio Canonica Mi7 Mi6 Albizzate Cesano M. Groane Biassono (Parco) Carnate Cesano M. Baruccana Seregno S1 S3 S9 Ceriano L. Groane Buttafava Bovisio M. Arcore Cavaria Mi6 Mi5 Villasanta Saronno Desio MXP Ceriano L. Malpensa Varedo Saronno Sud Lissone Monza Sobborghi Gallarate S30 Caronno P. Palazzolo M. Mi5 Cesate Monza Paderno D. Busto Arsizio (FS) Garbagnate S30 Mi9 MXP M1 Garbagnate P. Groane Cormano-C. Sesto I° Maggio (FS) Bignami M5 Sesto Rondò Mi4 Mi8 Legnano Bollate Nord M3 Bruzzano Comasina Ponale Mi5 Bollate Centro Sesto Marelli Canegrate Mi4 Novate Affori (FN) Bicocca Mi7 Mi3 Villa S. Giovanni Parabiago Quarto Oggiaro Ca’ Granda Greco Mi3 M2 Affori Centro Precotto Cologno Nord Mi6 MXP S2 Istria Vanzago Bovisa Rho Fiera Certosa Villapizzone Rho S13 Cologno Centro Dergano Gorla ecchi ea Marche rona o ita ola onietta Cologno Sud one o te Urbano dr ur ior omp Pregnana M. Maciachini nusc gonz S11 M1 imo er illa F assina de' Pusser illa P or essa Turro (Mi1) V C.na B C V C B V G C.na Ant G Urbano Lancetti Pero MXP C.na Gobba Vittuone (Mi1) P.