(De)Psychologizing Shangri-La: Recognizing and Reconsidering C.G

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum Vitae

Candidate for the Standing Committee Name Gabriela FREY Countries Germany, France Contact [email protected] Mobile 0033 609 77 29 85 Age born in 1962 Languages German, French, English, (Tibetan) • 2008 - Introducing the participatory status for the EBU and attending the Council sessions as official representative since then. of Europe • Contributing 4 years in the Human Rights Committee and the report on Human Rights & Religion. Conference • Participating regularly in the CM-Exchanges on the religious dimension of of INGOs intercultural dialogue until 2017. • Joining the GPPP working group (Gender Perspectives in Political Processes). • Co-Organising a side Event in the CoE: are Religions a place for emancipation for women? Progress and setbacks (2016) • Participating in the WG democratic decision making processes, concerning the school project “Religious education for all” in Hamburg • Since 2019 coordinator of the WG Intercultural Cities (Education Committee), aimed to research & report on "Reducing anxiety and exclusion through developing emotional balance and communication skills". • From 1988 until 2017 assistant to several German MEPs (i.a. in the areas European of transport, tourism, regional affairs, development, budget, foreign affairs) Parliament • Head of the Strasbourg office, organising, managing & supervising official visitor groups, delegation trips, industry panels, journalist campaigns, etc. • 16 years Secretary of the E.P.’s Tibet Intergroup (TIG), coordination monthly meetings and activities with relevant NGOs and specialists, organising exhibitions & charity sales. Coordinating visits of the Dalai Lama to Strasbourg and Brussels. Organising 4 delegations journeys of the TIG to Dharamsala (India) for exchanges with the Tibetan government in exile. • 2019 First guest speaker on Buddhism in Europe in the Interreligious Dialogue Unit of the EPP Group. -

Dharma Kings and Flying Women: Buddhist

DHARMA KINGS AND FLYING WOMEN: BUDDHIST EPISTEMOLOGIES IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY INDIAN AND BRITISH WRITING by CYNTHIA BETH DRAKE B.A., University of California at Berkeley, 1984 M.A.T., Oregon State University, 1992 M.A. Georgetown University, 1999 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English 2017 This thesis entitled: Dharma Kings and Flying Women: Buddhist Epistemologies in Early Twentieth-Century Indian and British Writing written by Cynthia Beth Drake has been approved for the Department of English ________________________________________ Dr. Laura Winkiel __________________________________________ Dr. Janice Ho Date ________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Drake, Cynthia Beth (Ph.D., English) Dharma Kings and Flying Women: Buddhist Epistemologies in Early Twentieth-Century Indian and British Writing Thesis directed by Associate Professor Laura Winkiel The British fascination with Buddhism and India’s Buddhist roots gave birth to an epistemological framework combining non-dual awareness, compassion, and liberational praxis in early twentieth-century Indian and British writing. Four writers—E.M. Forster, Jiddu Krishnamurti, Lama Yongden, and P.L. Travers—chart a transnational cartography that mark points of location in the flow and emergence of this epistemological framework. To Forster, non- duality is a terrifying rupture and an echo of not merely gross mismanagement, but gross misunderstanding by the British of India and its spiritual legacy. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

Tantra As Experimental Science in the Works of John Woodroffe

Julian Strube Tantra as Experimental Science in the Works of John Woodroffe Abstract: John Woodroffe (1865–1936) can be counted among the most influential authors on Indian religious traditions in the twentieth century. He is credited with almost single-handedly founding the academic study of Tantra, for which he served as a main reference well into the 1970s. Up to that point, it is practically impossible to divide his influence between esoteric and academic audiences – in fact, borders between them were almost non-existent. Woodroffe collaborated and exchangedthoughtswithscholarssuchasSylvainLévi,PaulMasson-Oursel,Moriz Winternitz, or Walter Evans-Wentz. His works exerted a significant influence on, among many others, Heinrich Zimmer, Jakob Wilhelm Hauer, Mircea Eliade, Carl Gustav Jung, Agehananda Bharati or Lilian Silburn, as they did on a wide range of esotericists such as Julius Evola. In this light, it is remarkable that Woodroffe did not only distance himself from missionary and orientalist approaches to Tantra, buthealsoidentifiedTantrawithCatholicism and occultism, introducing a univer- salist, traditionalist perspective. This was not simply a “Western” perspective, since Woodroffe echoed Bengali intellectuals who praised Tantra as the most appropriate and authen- tic religious tradition of India. In doing so, they stressed the rational, empiri- cal, scientific nature of Tantra that was allegedly based on practical spiritual experience. As Woodroffe would later do, they identified the practice of Tantra with New Thought, spiritualism, and occultism – sciences that were only re-discovering the ancient truths that had always formed an integral part of “Tantrik occultism.” This chapter situates this claim within the context of global debates about modernity and religion, demonstrating how scholarly approaches to religion did not only parallel, but were inherently intertwined with, occultist discourses. -

The Wild Irish Girl and the "Dalai Lama of Little Thibet": the Long Encounter Between Ireland and Asian Buddhism1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by MURAL - Maynooth University Research Archive Library The Wild Irish Girl and the "dalai lama of little Thibet": 1 the long encounter between Ireland and Asian Buddhism Laurence Cox and Maria Griffin Introduction Ireland lies on the margins of the Buddhist world, far from its homeland in northern India and Nepal and the traditionally Buddhist parts of Asia. It is also in various ways "peripheral" to core capitalist societies, and Irish encounters with Buddhism are structured by both facts. Buddhism, for its part, has been a central feature of major Eurasian societies for over two millennia. During this period, Irish people and Asian Buddhists have repeatedly encountered or heard about each other, in ways structured by many different kinds of global relations – from the Roman Empire and the medieval church via capitalist exploration, imperial expansion and finally contemporary capitalism. These different relationships have conditioned different kinds of encounters and outcomes. At the same time, as succeeding tides of empire, trade and knowledge have crossed Eurasia, each tide has left its traces. In 1859, Fermanagh-born James Tennent's best-selling History of Ceylon could devote four chapters to what was already known about the island in ancient and medieval times – by Greeks and Romans, by "Moors, Genoese and Venetians", by Indian, Arabic and Persian authors and in China. Similarly, the Catholic missionary D Nugent, speaking in Dublin's Mansion House in 1924, could discuss encounters with China from 1291 via the Jesuits to the present. -

{Download PDF} the Life of Milarepa

THE LIFE OF MILAREPA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Tsangnyon Heruka,Andrew Quintman | 304 pages | 05 May 2011 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780143106227 | English | London, United Kingdom The Life of Milarepa by Tsangnyön Heruka, Paperback | Barnes & Noble® Marpa, being aware that Milarepa had first of all to purify himself from the negative karma he had accumulated, exposed him to an extremely hard apprenticeship. But finally, Marpa gave Milarepa full transmissions of all the Mahamudra teachings from Naropa, Maitripa and other Indian masters. Practicing these teachings for many years in isolated mountain retreats, Milarepa attained enlightenment. He gained fame for his incredible perseverance in practice and for his spontaneous songs of realisation. Of his many students, Gampopa became his main lineage holder. The life of Milarepa From the Gungthang province of Western Tibet, close to Nepal, Milarepa had a hard childhood and a dark youth. Follow Karmapa on social media , Friends. As teacher Judy Lief, who edited this volume, put it:. Translations of many of Milarepa's songs are included in Rain of Wisdom , a collection of the songs of the Kagyu. There is a wonderful story that follows the song included here:. Milarepa called him back again. So I will teach it to you. Here it is! The qualities in my mind stream have arisen through my having meditated so persistently that my buttocks have become like this. You must also give rise to such heartfelt perseverance and meditate! In volume V of his Collected Works, he has three pieces:. The writing is quite vivid, however. Although it was impossible to definitively confirm this, it is likely that this article is actually an early treatment prepared by Chogyam Trungpa for a movie on the life of Milarepa, which he began filming in the early s. -

Alexandra David-Neel in Sikkim and the Making of Global Buddhism

Transcultural Studies 2016.1 149 On the Threshold of the “Land of Marvels:” Alexandra David-Neel in Sikkim and the Making of Global Buddhism Samuel Thévoz, Fellow, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation I look around and I see these giant mountains and my hermit hut. All of this is too fantastic to be true. I look into the past and watch things that happened to me and to others; […] I am giving lectures at the Sorbonne, I am an artist, a reporter, a writer; images of backstages, newsrooms, boats, railways unfold like in a movie. […] All of this is a show produced by shallow ghosts, all of this is brought into play by the imagination. There is no “self” or “others,” there is only an eternal dream that goes on, giving birth to transient characters, fictional adventures.1 An icon: Alexandra David-Neel in the global public sphere Alexandra David-Neel (Paris, 1868–Digne-les-bains, 1969)2 certainly ranks among the most celebrated of the Western Buddhist pioneers who popularized the modern perception of Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism at large.3 As is well known, it is her illegal trip from Eastern Tibet to Lhasa in 1924 that made her famous. Her global success as an intrepid explorer started with her first published travel narrative, My Journey to Lhasa, which was published in 1927 1 Alexandra David-Néel, Correspondance avec son mari, 1904–1941 (Paris: Plon, 2000), 392. Translations of all quoted letters are mine. 2 This work was supported by the Swiss National Foundation for Scientific Research under grant PA00P1_145398: http://p3.snf.ch/project-145398. -

Japanese Buddhism in Austria

Journal of Religion in Japan 10 (2021) 222–242 brill.com/jrj Japanese Buddhism in Austria Lukas Pokorny | orcid: 0000-0002-3498-0612 University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria [email protected] Abstract Drawing on archival research and interview data, this paper discusses the historical development as well as the present configuration of the Japanese Buddhist panorama in Austria, which includes Zen, Pure Land, and Nichiren Buddhism. It traces the early beginnings, highlights the key stages and activities in the expansion process, and sheds light on both denominational complexity and international entanglement. Fifteen years before any other European country (Portugal in 1998; Italy in 2000), Austria for- mally acknowledged Buddhism as a legally recognised religious society in 1983. Hence, the paper also explores the larger organisational context of the Österreichische Bud- dhistische Religionsgesellschaft (Austrian Buddhist Religious Society) with a focus on its Japanese Buddhist actors. Additionally, it briefly outlines the non-Buddhist Japanese religious landscape in Austria. Keywords Japanese Buddhism – Austria – Zen – Nichirenism – Pure Land Buddhism 1 A Brief Historical Panorama The humble beginnings of Buddhism in Austria go back to Vienna-based Karl Eugen Neumann (1865–1915), who, inspired by his readings of Arthur Schopen- hauer (1788–1860), like many others after him, turned to Buddhism in 1884. A trained Indologist with a doctoral degree from the University of Leipzig (1891), his translations from the Pāli Canon posthumously gained seminal sta- tus within the nascent Austrian Buddhist community over the next decades. His knowledge of (Indian) Mahāyāna thought was sparse and his assessment thereof was polemically negative (Hecker 1986: 109–111). -

European Buddhist Traditions Laurence Cox, National University

European Buddhist Traditions Laurence Cox, National University of Ireland Maynooth Abstract: This chapter covers those Buddhist traditions which are largely based in Europe, noting some of the specificities of this history as against the North American with which it is sometimes conflated. While the reception history of Buddhism in Europe stretches back to Alexander, Buddhist organization in Europe begins in the later nineteenth century, with the partial exception of indigenous Buddhisms in the Russian Empire. The chapter discusses Asian- oriented Buddhisms with a strong European base; European neo-traditionalisms founded by charismatic individuals; explicitly new beginnings; and the broader world of “fuzzy religion” with Buddhist components, including New Age, “night-stand Buddhists”, Christian creolizations, secular mindfulness and engaged Buddhism. In general terms European Buddhist traditions reproduce the wider decline of religious institutionalization and boundary formation that shapes much of European religion generally. Keywords: Buddhism, Buddhist modernism, creolization, Europe, immigration, meditation, night-stand Buddhists, Western Buddhism In 1908, the London investigative weekly Truth hosted a debate between two Burmese- ordained European bhikkhus (monks), U Dhammaloka (Laurence Carroll?) and Ananda Metteyya (Allan Bennett). Objecting to newspaper reports presenting the latter, recently arrived in Britain, as the first bhikkhu in Europe, Dhammaloka argued on July 8th that Ananda Metteyya had not been properly ordained, citing the Upasampada-Kammavacana to show that ordinands must state their freedom from various diseases, including asthma (which Bennett suffered from). Ananda Metteyya replied on July 15th with a discussion of the Burmese Kammavacana and the Mahavagga and stated that he had believed himself cured at the time of ordination. -

The Tibetan Tetralogy of W.Y. Evans-Wentz

Winter 2015 The Tibetan Tetralogy of W. Y. Evans-Wentz: A Retrospective Assessment - Part I Iván Kovács 1 The Dharma-Kaya of thine own mind thou shalt see; and seeing That, thou shalt have seen the All – The Vision Infinite, the Round of Death and Birth and the State of Freedom. Milarepa, Jetsun-Khabum2 Abstract Woodroffe, and W. Y. Evans-Wentz’s own comments. When appropriate, excerpts from his article is part of a series of articles the texts of the translations are themselves th T dealing with four early 20 century Tibet- sampled and discussed, and often comparisons ologists. The first article of the series dealt and parallels drawn between various schools of with the life and work of the French Tibetolo- thinking, so that the texts are thereby more gist, Alexandra David-Néel, and was published colorfully elucidated. The conclusion briefly in the Winter 2014 issue of the Esoteric Quar- discusses the merits and sincerity of Evans- terly. The present article takes a closer look at the life and work of the American Tibetologist, _____________________________________ W. Y. Evans-Wentz. It begins with his biog- About the Author raphy, which mainly deals with his travels and Iván Kovács is qualified as a fine artist. As a writer the circumstances of his scholarship and writ- he has published art criticism, short stories and po- ing. This is followed by a short summary of his ems, and more recently, articles of an esoteric na- Tibetan tetralogy. Then each of his four books ture. He is a reader of the classics and modern clas- is discussed in greater detail, including the sics, a lover of world cinema, as well as classical commentaries and forewords by scholars and and contemporary music. -

Buddhism from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation, Search

Buddhism From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search A statue of Gautama Buddha in Bodhgaya, India. Bodhgaya is traditionally considered the place of his awakening[1] Part of a series on Buddhism Outline · Portal History Timeline · Councils Gautama Buddha Disciples Later Buddhists Dharma or Concepts Four Noble Truths Dependent Origination Impermanence Suffering · Middle Way Non-self · Emptiness Five Aggregates Karma · Rebirth Samsara · Cosmology Practices Three Jewels Precepts · Perfections Meditation · Wisdom Noble Eightfold Path Wings to Awakening Monasticism · Laity Nirvāṇa Four Stages · Arhat Buddha · Bodhisattva Schools · Canons Theravāda · Pali Mahāyāna · Chinese Vajrayāna · Tibetan Countries and Regions Related topics Comparative studies Cultural elements Criticism v • d • e Buddhism (Pali/Sanskrit: बौद धमर Buddh Dharma) is a religion and philosophy encompassing a variety of traditions, beliefs and practices, largely based on teachings attributed to Siddhartha Gautama, commonly known as the Buddha (Pāli/Sanskrit "the awakened one"). The Buddha lived and taught in the northeastern Indian subcontinent some time between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE.[2] He is recognized by adherents as an awakened teacher who shared his insights to help sentient beings end suffering (or dukkha), achieve nirvana, and escape what is seen as a cycle of suffering and rebirth. Two major branches of Buddhism are recognized: Theravada ("The School of the Elders") and Mahayana ("The Great Vehicle"). Theravada—the oldest surviving branch—has a widespread following in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, and Mahayana is found throughout East Asia and includes the traditions of Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren Buddhism, Tibetan Buddhism, Shingon, Tendai and Shinnyo-en. In some classifications Vajrayana, a subcategory of Mahayana, is recognized as a third branch. -

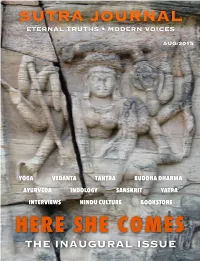

The Inaugural Issue Sutra Journal • Aug/2015 • Issue 1

SUTRA JOURNAL ETERNAL TRUTHS • MODERN VOICES AUG/2015 YOGA VEDANTA TANTRA BUDDHA DHARMA AYURVEDA INDOLOGY SANSKRIT YATRA INTERVIEWS HINDU CULTURE BOOKSTORE HERE SHE COMES THE INAUGURAL ISSUE SUTRA JOURNAL • AUG/2015 • ISSUE 1 Invocation 2 Editorial 3 What is Dharma? Pankaj Seth 9 Fritjof Capra and the Dharmic worldview Aravindan Neelakandan 15 Vedanta is self study Chris Almond 32 Yoga and four aims of life Pankaj Seth 37 The Gita and me Phil Goldberg 41 Interview: Anneke Lucas - Liberation Prison Yoga 45 Mantra: Sthaneshwar Timalsina 56 Yatra: India and the sacred • multimedia presentation 67 If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him Vikram Zutshi 69 Buddha: Nibbana Sutta 78 Who is a Hindu? Jeffery D. Long 79 An introduction to the Yoga Vasistha Mary Hicks 90 Sankalpa Molly Birkholm 97 Developing a continuity of practice Virochana Khalsa 101 In appreciation of the Gita Jeffery D. Long 109 The role of devotion in yoga Bill Francis Barry 113 Road to Dharma Brandon Fulbrook 120 Ayurveda: The list of foremost things 125 Critics corner: Yoga as the colonized subject Sri Louise 129 Meditation: When the thunderbolt strikes Kathleen Reynolds 137 Devata: What is deity worship? 141 Ganesha 143 1 All rights reserved INVOCATION O LIGHT, ILLUMINATE ME RG VEDA Tree shrine at Vijaynagar EDITORIAL Welcome to the inaugural issue of Sutra Journal, a free, monthly online magazine with a Dharmic focus, fea- turing articles on Yoga, Vedanta, Tantra, Buddhism, Ayurveda, and Indology. Yoga arose and exists within the Dharma, which is a set of timeless teachings, holistic in nature, covering the gamut from the worldly to the metaphysical, from science to art to ritual, incorporating Vedanta, Tantra, Bud- dhism, Ayurveda, and other dimensions of what has been brought forward by the Indian civilization.