The Buddha at Eranos

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revue D'etudes Tibétaines

Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines Perspectives on Tibetan Culture A Small Garland of Forget-me-nots Offered to Elena De Rossi Filibeck Edited by Michela Clemente, Oscar Nalesini and Federica Venturi numéro cinquante-et-un — Juillet 2019 PERSPECTIVES ON TIBETAN CULTURE PERSPECTIVES ON TIBETAN CULTURE A Small Garland of Forget-me-nots Offered to Elena De Rossi Filibeck Edited by MICHELA CLEMENTE, OSCAR NALESINI AND FEDERICA VENTURI Perspectives on Tibetan Culture. A Small Garland of Forget-me-nots Offered to Elena De Rossi Filibeck Edited by Michela Clemente, Oscar Nalesini and Federica Venturi Copyright © 2019: each author holds the copyright of her/his contribution to this book All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the authors. Elena De Rossi Filibeck in Ladakh, 2005. Photo: Courtesy of Beatrice Filibeck Table of Contents Introduction 1 Tabula Gratulatoria 3 Elena De Rossi Filibeck’s Publications 5 1. Alessandro Boesi “dByar rtswa dgun ’bu is a Marvellous Thing”. Some Notes on the Concept of Ophiocordyceps sinensis among Tibetan People and its Significance in Tibetan Medicine 15 2. John Bray Ladakhi Knowledge and Western Learning: A. H. Francke’s Teachers, Guides and Friends in the Western Himalaya 39 3. Michela Clemente A Condensed Catalogue of 16th Century Tibetan Xylographs from South- Western Tibet 73 4. Mauro Crocenzi The Historical Development of Tibetan “Minzu” Identity through Chinese Eyes: A Preliminary Analysis 99 5. Franz Karl Ehrhard and Marta Sernesi Apropos a Recent Collection of Tibetan Xylographs from the 15th to the 17th Centuries 119 6. -

Preparatory Document

Preparatory document Please notice that we recommend that you read the first ten pages of the first three documents, the last document is optional. • International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, Recognizing and Countering Holocaust Distortion: Recommendations for Policy and Decision Makers (Berlin: International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, 2021), read esp. pp. 14-24 • Deborah Lipstadt, "Holocaust Denial: An Antisemitic Fantasy," Modern Judaism 40:1 (2020): 71-86 • Keith Kahn Harris, "Denialism: What Drives People to Reject the Truth," The Guardian, 3 August 2018, as at https://www.theguardian.com/news/2018/aug/03/denialism-what-drives- people-to-reject-the-truth (attached as pdf) • Optional reading: Giorgio Resta and Vincenzo Zeno-Zencovich, "Judicial 'Truth' and Historical 'Truth': The Case of the Ardeatine Caves Massacre," Law and History Review 31:4 (2013): 843- 886 Holocaust Denial: An Antisemitic Fantasy Deborah Lipstadt Modern Judaism, Volume 40, Number 1, February 2020, pp. 71-86 (Article) Published by Oxford University Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/750387 [ Access provided at 15 Feb 2021 12:42 GMT from U S Holocaust Memorial Museum ] Deborah Lipstadt HOLOCAUST DENIAL: AN ANTISEMITIC FANTASY* *** When I first began working on the topic of Holocaust deniers, colleagues would frequently tell me I was wasting my time. “These people are dolts. They are the equivalent of flat-earth theorists,” they would insist. “Forget about them.” In truth, I thought the same thing. In fact, when I first heard of Holocaust deniers, I laughed and dismissed them as not worthy of serious analysis. Then I looked more closely and I changed my mind. -

SYMPOSIUM Moving Borders: Tibet in Interaction with Its Neighbors

SYMPOSIUM Moving Borders: Tibet in Interaction with Its Neighbors Symposium participants and abstracts: Karl Debreczeny is Senior Curator of Collections and Research at the Rubin Museum of Art. He completed his PhD in Art History at the University of Chicago in 2007. He was a Fulbright‐Hays Fellow (2003–2004) and a National Gallery of Art CASVA Ittleson Fellow (2004–2006). His research focuses on exchanges between Tibetan and Chinese artistic traditions. His publications include The Tenth Karmapa and Tibet’s Turbulent Seventeenth Century (ed. with Tuttle, 2016); The All‐Knowing Buddha: A Secret Guide (with Pakhoutova, Luczanits, and van Alphen, 2014); Situ Panchen: Creation and Cultural Engagement in Eighteenth‐Century Tibet (ed., 2013); The Black Hat Eccentric: Artistic Visions of the Tenth Karmapa (2012); and Wutaishan: Pilgrimage to Five Peak Mountain (2011). His current projects include an exhibition which explores the intersection of politics, religion, and art in Tibetan Buddhism across ethnicities and empires from the seventh to nineteenth century. Art, Politics, and Tibet’s Eastern Neighbors Tibetan Buddhism’s dynamic political role was a major catalyst in moving the religion beyond Tibet’s borders east to its Tangut, Mongol, Chinese, and Manchu neighbors. Tibetan Buddhism was especially attractive to conquest dynasties as it offered both a legitimizing model of universal sacral kingship that transcended ethnic and clan divisions—which could unite disparate people—and also promised esoteric means to physical power (ritual magic) that could be harnessed to expand empires. By the twelfth century Tibetan masters became renowned across northern Asia as bestowers of this anointed rule and occult power. -

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

John Cage's Entanglement with the Ideas Of

JOHN CAGE’S ENTANGLEMENT WITH THE IDEAS OF COOMARASWAMY Edward James Crooks PhD University of York Music July 2011 John Cage’s Entanglement with the Ideas of Coomaraswamy by Edward Crooks Abstract The American composer John Cage was famous for the expansiveness of his thought. In particular, his borrowings from ‘Oriental philosophy’ have directed the critical and popular reception of his works. But what is the reality of such claims? In the twenty years since his death, Cage scholars have started to discover the significant gap between Cage’s presentation of theories he claimed he borrowed from India, China, and Japan, and the presentation of the same theories in the sources he referenced. The present study delves into the circumstances and contexts of Cage’s Asian influences, specifically as related to Cage’s borrowings from the British-Ceylonese art historian and metaphysician Ananda K. Coomaraswamy. In addition, Cage’s friendship with the Jungian mythologist Joseph Campbell is detailed, as are Cage’s borrowings from the theories of Jung. Particular attention is paid to the conservative ideology integral to the theories of all three thinkers. After a new analysis of the life and work of Coomaraswamy, the investigation focuses on the metaphysics of Coomaraswamy’s philosophy of art. The phrase ‘art is the imitation of nature in her manner of operation’ opens the doors to a wide- ranging exploration of the mimesis of intelligible and sensible forms. Comparing Coomaraswamy’s ‘Traditional’ idealism to Cage’s radical epistemological realism demonstrates the extent of the lack of congruity between the two thinkers. In a second chapter on Coomaraswamy, the extent of the differences between Cage and Coomaraswamy are revealed through investigating their differing approaches to rasa , the Renaissance, tradition, ‘art and life’, and museums. -

Tantra As Experimental Science in the Works of John Woodroffe

Julian Strube Tantra as Experimental Science in the Works of John Woodroffe Abstract: John Woodroffe (1865–1936) can be counted among the most influential authors on Indian religious traditions in the twentieth century. He is credited with almost single-handedly founding the academic study of Tantra, for which he served as a main reference well into the 1970s. Up to that point, it is practically impossible to divide his influence between esoteric and academic audiences – in fact, borders between them were almost non-existent. Woodroffe collaborated and exchangedthoughtswithscholarssuchasSylvainLévi,PaulMasson-Oursel,Moriz Winternitz, or Walter Evans-Wentz. His works exerted a significant influence on, among many others, Heinrich Zimmer, Jakob Wilhelm Hauer, Mircea Eliade, Carl Gustav Jung, Agehananda Bharati or Lilian Silburn, as they did on a wide range of esotericists such as Julius Evola. In this light, it is remarkable that Woodroffe did not only distance himself from missionary and orientalist approaches to Tantra, buthealsoidentifiedTantrawithCatholicism and occultism, introducing a univer- salist, traditionalist perspective. This was not simply a “Western” perspective, since Woodroffe echoed Bengali intellectuals who praised Tantra as the most appropriate and authen- tic religious tradition of India. In doing so, they stressed the rational, empiri- cal, scientific nature of Tantra that was allegedly based on practical spiritual experience. As Woodroffe would later do, they identified the practice of Tantra with New Thought, spiritualism, and occultism – sciences that were only re-discovering the ancient truths that had always formed an integral part of “Tantrik occultism.” This chapter situates this claim within the context of global debates about modernity and religion, demonstrating how scholarly approaches to religion did not only parallel, but were inherently intertwined with, occultist discourses. -

Alexandra David-Neel in Sikkim and the Making of Global Buddhism

Transcultural Studies 2016.1 149 On the Threshold of the “Land of Marvels:” Alexandra David-Neel in Sikkim and the Making of Global Buddhism Samuel Thévoz, Fellow, The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation I look around and I see these giant mountains and my hermit hut. All of this is too fantastic to be true. I look into the past and watch things that happened to me and to others; […] I am giving lectures at the Sorbonne, I am an artist, a reporter, a writer; images of backstages, newsrooms, boats, railways unfold like in a movie. […] All of this is a show produced by shallow ghosts, all of this is brought into play by the imagination. There is no “self” or “others,” there is only an eternal dream that goes on, giving birth to transient characters, fictional adventures.1 An icon: Alexandra David-Neel in the global public sphere Alexandra David-Neel (Paris, 1868–Digne-les-bains, 1969)2 certainly ranks among the most celebrated of the Western Buddhist pioneers who popularized the modern perception of Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism at large.3 As is well known, it is her illegal trip from Eastern Tibet to Lhasa in 1924 that made her famous. Her global success as an intrepid explorer started with her first published travel narrative, My Journey to Lhasa, which was published in 1927 1 Alexandra David-Néel, Correspondance avec son mari, 1904–1941 (Paris: Plon, 2000), 392. Translations of all quoted letters are mine. 2 This work was supported by the Swiss National Foundation for Scientific Research under grant PA00P1_145398: http://p3.snf.ch/project-145398. -

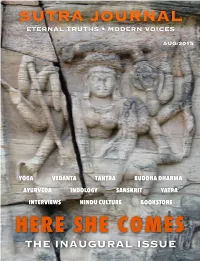

The Inaugural Issue Sutra Journal • Aug/2015 • Issue 1

SUTRA JOURNAL ETERNAL TRUTHS • MODERN VOICES AUG/2015 YOGA VEDANTA TANTRA BUDDHA DHARMA AYURVEDA INDOLOGY SANSKRIT YATRA INTERVIEWS HINDU CULTURE BOOKSTORE HERE SHE COMES THE INAUGURAL ISSUE SUTRA JOURNAL • AUG/2015 • ISSUE 1 Invocation 2 Editorial 3 What is Dharma? Pankaj Seth 9 Fritjof Capra and the Dharmic worldview Aravindan Neelakandan 15 Vedanta is self study Chris Almond 32 Yoga and four aims of life Pankaj Seth 37 The Gita and me Phil Goldberg 41 Interview: Anneke Lucas - Liberation Prison Yoga 45 Mantra: Sthaneshwar Timalsina 56 Yatra: India and the sacred • multimedia presentation 67 If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him Vikram Zutshi 69 Buddha: Nibbana Sutta 78 Who is a Hindu? Jeffery D. Long 79 An introduction to the Yoga Vasistha Mary Hicks 90 Sankalpa Molly Birkholm 97 Developing a continuity of practice Virochana Khalsa 101 In appreciation of the Gita Jeffery D. Long 109 The role of devotion in yoga Bill Francis Barry 113 Road to Dharma Brandon Fulbrook 120 Ayurveda: The list of foremost things 125 Critics corner: Yoga as the colonized subject Sri Louise 129 Meditation: When the thunderbolt strikes Kathleen Reynolds 137 Devata: What is deity worship? 141 Ganesha 143 1 All rights reserved INVOCATION O LIGHT, ILLUMINATE ME RG VEDA Tree shrine at Vijaynagar EDITORIAL Welcome to the inaugural issue of Sutra Journal, a free, monthly online magazine with a Dharmic focus, fea- turing articles on Yoga, Vedanta, Tantra, Buddhism, Ayurveda, and Indology. Yoga arose and exists within the Dharma, which is a set of timeless teachings, holistic in nature, covering the gamut from the worldly to the metaphysical, from science to art to ritual, incorporating Vedanta, Tantra, Bud- dhism, Ayurveda, and other dimensions of what has been brought forward by the Indian civilization. -

The Japanese Warrior in the Cultural Production of Fascist Italy

Revista de Artes Marciales Asiáticas Volumen 12(2), 82100 ~ JulioDiciembre 2017 DOI: 10.18002/rama.v12i2.5157 RAMA I.S.S.N. 2174‐0747 http://revpubli.unileon.es/ojs/index.php/artesmarciales Bushido as allied: The Japanese warrior in the cultural production of Fascist Italy (19401943) Sergio RAIMONDO*1,2, Valentina DE FORTUNA3, & Giulia CECCARELLI3 1 University of Cassino and South Lazio (Italy) 2 Area Discipline Orientali Unione Italiana Sport per Tutti (Italy) 3 Free Lance Translator (Italy) Recepción: 17/10/2017; Aceptación: 19/12/2017; Publicación: 27/12/2017. ORIGINAL PAPER Abstract Introduction: After the signing of the alliance among Japan, Germany and Italy’s governments in September 1940, several journals arose in order to spread the Japanese culture among people who knew very little about Italy’s new allied. Some documentaries also had the same function. Methods: The numerous textual and iconographical references concerning the Japanese warriors’ anthropology published in some Italian magazines during the 1940s have been compared, as well as to the few Italian monographs on the same theme and to some documentaries by Istituto Nazionale Luce, government propaganda organ. This subject has also been compared to the first Italian cultural production, concerning Japan, which dated back to the first decades of the 20th century. Moreover different intellectuals’ biographies of those times have been deeply analyzed. Results: Comparing to each other the anthropological references about Japan in the Italian cultural production during the Second World War, we can notice a significant ideological homogeneity. This can be explained through their writers’ common sharing of the militaristic, hierarchical and totalitarian doctrine of the Fascist Regime. -

Nonattachment and Ethics in Yoga Traditions

This is a repository copy of "A petrification of one's own humanity"? Nonattachment and ethics in yoga traditions. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/85285/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Burley, M (2014) "A petrification of one's own humanity"? Nonattachment and ethics in yoga traditions. Journal of Religion, 94 (2). 204 - 228. ISSN 0022-4189 https://doi.org/10.1086/674955 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ “A Petrification of One’s Own Humanity”? Nonattachment and Ethics in Yoga Traditions* Mikel Burley / University of Leeds In this yogi-ridden age, it is too readily assumed that ‘non-attachment’ is not only better than a full acceptance of earthly life, but that the ordinary man only rejects it because it is too difficult: in other words, that the average human being is a failed saint. -

Review of the Great Awakening

The sociological implications for contemporary Buddhism in the UK: socially engaged Buddhism, a case study Item Type Article Authors Henry, Philip M. Citation Henry, Philip M. (2006) 'The sociological implications for contemporary Buddhism in the UK: socially engaged Buddhism, a case study', Journal of Buddhist Ethics, Vol. 13 Publisher Dickinson Blogs Journal Journal of Buddhist Ethics Download date 25/09/2021 17:20:16 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10545/335908 Journal of Buddhist Ethics ISSN 1076-9005 http://jbe.gold.ac.uk/ The Sociological Implications for Contemporary Buddhism in the United Kingdom: Socially Engaged Buddhism, a Case Study Phil Henry University of Derby Email: [email protected] Copyright Notice: Digital copies of this work may be made and dis- tributed provided no change is made and no alteration is made to the content. Reproduction in any other format, with the exception of a single copy for private study, requires the written permission of the au- thor. All enquiries to: [email protected] The Sociological Implications for Contemporary Buddhism in the United Kingdom: Socially Engaged Buddhism, a Case Study Phil Henry University of Derby Email: [email protected] Introduction Buddhist Studies has, for well over a century, been seen by many in the acad- emy as the domain of philologists and others whose skills are essentially in the translation and interpretation of texts derived from ancient languages like classical Chinese, Pāli, Sanskrit, and its hybrid variations, together with the commentarial tradition that developed alongside it. Only in the last thirty-five years has there been an increasing number of theses, journal articles, and other academic texts that have seriously addressed the developments of a Western Buddhism as opposed to Buddhism in the West. -

From Padmasambhava to Gö Tsangpa: Rethinking Religious Patronage in the Indian Himalayas Between the 8Th and 13Th Centuries

_full_alt_author_running_head (neem stramien B2 voor dit chapter en dubbelklik nul hierna en zet 2 auteursnamen neer op die plek met and): Mein- ert and Sørensen _full_articletitle_deel (kopregel rechts, vul hierna in): Rethinking Religious Patronage in the Indian Himalayas, 8th–13th c. _full_article_language: en indien anders: engelse articletitle: 0 Rethinking Religious Patronage in the Indian Himalayas, 8th–13th c. 151 Chapter 6 From Padmasambhava to Gö Tsangpa: Rethinking Religious Patronage in the Indian Himalayas between the 8th and 13th Centuries Verena Widorn 1 Introduction1 Authenticity—in all its various aspects2—seems to be one of the most re- quired criterions when analysing an object of art. The questions of authentic- ity of provenance and originality in particular are of major importance for western art historians. The interest in genuine workmanship, the knowledge of an exact date, and chronology keep scholars occupied in their search for prop- er timelines and the artistic lineages of monuments and artefacts. The time of 1 I especially wish to express my gratitude to Carmen Meinert and her team for the generous invitation to the start-up conference of her ERC project BuddhistRoad, which gave me the opportunity to present and now to publish a topic that has been on my mind for several years and was supported through several field trips to pilgrimage sites in Himachal Pradesh. Still, this study is just a first attempt to express my uneasiness with the manner in which academic studies forces western concepts of authenticity onto otherwise hagiographic ideals. I am also thankful to Max Deeg and Lewis Doney for their critical and efficient comments on my paper during the conference.