Reinvestigating Vestium, One of the Spurious Platinum Metals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Osmium(II) Polypyridyl Complexes Wesley R. Browne a Thesis Pres

Probing ground and excited state properties of Ruthenium(II) and Osmium(II) polypyridyl complexes Wesley R. Browne A Thesis presented to Dublin City University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 2002 Probing ground and excited state properties of Ruthenium(II) and Osmium(II) polypyridyl complexes Isotope, pH, solvent and temperature effects. by Wesley R. Browne, BSc.(Hons), AMRSC A Thesis presented to Dublin City University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Supervisor: Professor Johannes G. Vos School of Chemical Sciences Dublin City University August 2002 Dedicated to Matthew & to the memory of Ross and Mick “Caste a cold eye on life, on death. Horseman pass by” Epitaph fo r William Butler Yeats REFERENCE I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Doctor of Philosophy by research and thesis, is entirely my own work and has not been taken from work of others, save and to the extent that such work has been cited within the text of my work. I D. No. 95478965 Date:_______ ( ( / Û / iv Abstract The area of ruthenium(H) and osmium(H) polypyridyl chemistry has been the subject of intense investigation over the last half century. In chapter 1, topics relevant to the studies presented in this thesis are introduced. These areas include the basic principles behind the ground and excited state properties of Ru(II) and Os(II) polypyridyl complexes, complexes incorporating the 1,2,4-triazole moiety and the application of deuteriation to inorganic photophysics. Chapter 2 details experimental and basic synthetic procedures employed in the studies presented in later chapters. -

Historical Development of the Periodic Classification of the Chemical Elements

THE HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE PERIODIC CLASSIFICATION OF THE CHEMICAL ELEMENTS by RONALD LEE FFISTER B. S., Kansas State University, 1962 A MASTER'S REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree FASTER OF SCIENCE Department of Physical Science KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 196A Approved by: Major PrafeLoor ii |c/ TABLE OF CONTENTS t<y THE PROBLEM AND DEFINITION 0? TEH-IS USED 1 The Problem 1 Statement of the Problem 1 Importance of the Study 1 Definition of Terms Used 2 Atomic Number 2 Atomic Weight 2 Element 2 Periodic Classification 2 Periodic Lav • • 3 BRIEF RtiVJiM OF THE LITERATURE 3 Books .3 Other References. .A BACKGROUND HISTORY A Purpose A Early Attempts at Classification A Early "Elements" A Attempts by Aristotle 6 Other Attempts 7 DOBEREBIER'S TRIADS AND SUBSEQUENT INVESTIGATIONS. 8 The Triad Theory of Dobereiner 10 Investigations by Others. ... .10 Dumas 10 Pettehkofer 10 Odling 11 iii TEE TELLURIC EELIX OF DE CHANCOURTOIS H Development of the Telluric Helix 11 Acceptance of the Helix 12 NEWLANDS' LAW OF THE OCTAVES 12 Newlands' Chemical Background 12 The Law of the Octaves. .........' 13 Acceptance and Significance of Newlands' Work 15 THE CONTRIBUTIONS OF LOTHAR MEYER ' 16 Chemical Background of Meyer 16 Lothar Meyer's Arrangement of the Elements. 17 THE WORK OF MENDELEEV AND ITS CONSEQUENCES 19 Mendeleev's Scientific Background .19 Development of the Periodic Law . .19 Significance of Mendeleev's Table 21 Atomic Weight Corrections. 21 Prediction of Hew Elements . .22 Influence -

The Development of the Periodic Table and Its Consequences Citation: J

Firenze University Press www.fupress.com/substantia The Development of the Periodic Table and its Consequences Citation: J. Emsley (2019) The Devel- opment of the Periodic Table and its Consequences. Substantia 3(2) Suppl. 5: 15-27. doi: 10.13128/Substantia-297 John Emsley Copyright: © 2019 J. Emsley. This is Alameda Lodge, 23a Alameda Road, Ampthill, MK45 2LA, UK an open access, peer-reviewed article E-mail: [email protected] published by Firenze University Press (http://www.fupress.com/substantia) and distributed under the terms of the Abstract. Chemistry is fortunate among the sciences in having an icon that is instant- Creative Commons Attribution License, ly recognisable around the world: the periodic table. The United Nations has deemed which permits unrestricted use, distri- 2019 to be the International Year of the Periodic Table, in commemoration of the 150th bution, and reproduction in any medi- anniversary of the first paper in which it appeared. That had been written by a Russian um, provided the original author and chemist, Dmitri Mendeleev, and was published in May 1869. Since then, there have source are credited. been many versions of the table, but one format has come to be the most widely used Data Availability Statement: All rel- and is to be seen everywhere. The route to this preferred form of the table makes an evant data are within the paper and its interesting story. Supporting Information files. Keywords. Periodic table, Mendeleev, Newlands, Deming, Seaborg. Competing Interests: The Author(s) declare(s) no conflict of interest. INTRODUCTION There are hundreds of periodic tables but the one that is widely repro- duced has the approval of the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) and is shown in Fig.1. -

The Periodic Table of Elements

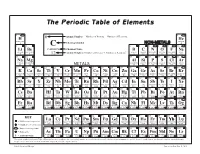

The Periodic Table of Elements 1 2 6 Atomic Number = Number of Protons = Number of Electrons HYDROGENH HELIUMHe 1 Chemical Symbol NON-METALS 4 3 4 C 5 6 7 8 9 10 Li Be CARBON Chemical Name B C N O F Ne LITHIUM BERYLLIUM = Number of Protons + Number of Neutrons* BORON CARBON NITROGEN OXYGEN FLUORINE NEON 7 9 12 Atomic Weight 11 12 14 16 19 20 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 SODIUMNa MAGNESIUMMg ALUMINUMAl SILICONSi PHOSPHORUSP SULFURS CHLORINECl ARGONAr 23 24 METALS 27 28 31 32 35 40 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 POTASSIUMK CALCIUMCa SCANDIUMSc TITANIUMTi VANADIUMV CHROMIUMCr MANGANESEMn FeIRON COBALTCo NICKELNi CuCOPPER ZnZINC GALLIUMGa GERMANIUMGe ARSENICAs SELENIUMSe BROMINEBr KRYPTONKr 39 40 45 48 51 52 55 56 59 59 64 65 70 73 75 79 80 84 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 RUBIDIUMRb STRONTIUMSr YTTRIUMY ZIRCONIUMZr NIOBIUMNb MOLYBDENUMMo TECHNETIUMTc RUTHENIUMRu RHODIUMRh PALLADIUMPd AgSILVER CADMIUMCd INDIUMIn SnTIN ANTIMONYSb TELLURIUMTe IODINEI XeXENON 85 88 89 91 93 96 98 101 103 106 108 112 115 119 122 128 127 131 55 56 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 CESIUMCs BARIUMBa HAFNIUMHf TANTALUMTa TUNGSTENW RHENIUMRe OSMIUMOs IRIDIUMIr PLATINUMPt AuGOLD MERCURYHg THALLIUMTl PbLEAD BISMUTHBi POLONIUMPo ASTATINEAt RnRADON 133 137 178 181 184 186 190 192 195 197 201 204 207 209 209 210 222 87 88 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 FRANCIUMFr RADIUMRa RUTHERFORDIUMRf DUBNIUMDb SEABORGIUMSg BOHRIUMBh HASSIUMHs MEITNERIUMMt DARMSTADTIUMDs ROENTGENIUMRg COPERNICIUMCn NIHONIUMNh -

Hjalmar Fors, the Limits of Matter—Chemistry, Mining & Enlightenment

Miner Econ (2015) 28:131–132 DOI 10.1007/s13563-015-0071-2 BOOK REVIEW Hjalmar Fors, The Limits of Matter—Chemistry, mining & enlightenment The University of Chicago Press Chicago USA 2015 Magnus Ericsson1 Published online: 15 September 2015 # Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2015 Swedish chemists have discovered more elements than scien- though at that time not united into one yet), France and tists from any other nation. Over more than 100 years, from England? Part of the answer is surprisingly bureaucratisation the early 18th century to the end of the 19th century, 20 ele- or the creation of an administrative institution called ments of which 18 metals or non-metals and 2 gases, nitrogen Bergskollegium in Swedish or English Bureau of Mines as and chlorine were independently isolated and described. Some Hjalmar Fors calls it in his new and path-breaking study of these are as follows: The Limits of Matter—Chemistry, mining & enlightenment. Another part is the need of improved processes and better Element Name Year of discovery yields in Swedish mines, which played such a vital role in Cobalt Brandt 1735 the Swedish economy during this period. The Swedish ruling Nickel Cronstedt 1751 groups saw these demands and founded the Bureau of Mines, Manganese Gahn 1774 which acted in several ways to solve problems, that had arisen in the mining industry. R&D in those days was highly Molybdenum Hjelm 1781 applied but nevertheless led to important purely scientific Yttrium Gadolin 1794 results. Tantalum Ekeberg 1802 The Bureau was set up in 1634 based on a predecessor, Cerium Berzelius 1803 which was started already in 1630. -

Iron-Catalyzed Reactions and X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopic Studies

Arnar Guðmundsson Iron-Catalyzed Reactions and X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopic Studies of Palladium- and Iron-Catalyzed Reactions and X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopic Studies of Palladium- and Ruthenium-Catalyzed Reactions and Ruthenium-Catalyzed Studies of Palladium- Absorption Spectroscopic Reactions and X-Ray Iron-Catalyzed Ruthenium-Catalyzed Reactions Arnar Guðmundsson Arnar Guðmundsson was born in Reykjavík, Iceland. After finishing his bachelor studies in biochemistry at the University of Iceland, he moved to Sweden to pursue his masters and doctoral studies under the guidance of Prof. Jan-Erling Bäckvall. ISBN 978-91-7911-264-6 Department of Organic Chemistry Doctoral Thesis in Organic Chemistry at Stockholm University, Sweden 2020 Iron-Catalyzed Reactions and X-Ray Absorption Spectroscopic Studies of Palladium- and Ruthenium-Catalyzed Reactions Arnar Guðmundsson Academic dissertation for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Organic Chemistry at Stockholm University to be publicly defended on Friday 22 January 2021 at 10.00 in Magnélisalen, Kemiska övningslaboratoriet, Svante Arrhenius väg 16 B. Abstract The focus of this thesis is twofold: The first is on the application of iron catalysis for organic transformations. The second is on the use of in situ X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS) to investigate the mechanisms of a heterogeneous palladium- catalyzed reaction and a homogeneous ruthenium-catalyzed reaction. In chapters two, three and four, the use of iron catalyst VI, or its analog X, is described for (I) the DKR of sec-alcohols to produce enantiomerically pure acetates; (II) the cycloisomerization of α-allenols and α-allenic sulfonamides, giving 2,3-dihydrofuran or 2,3-dihydropyrrole products, respectively, with excellent diastereoselectivity; and (III) the aerobic biomimetic oxidation of primary- and secondary alcohols to their respective aldehydes or ketones. -

The Separation and Determination of Osmium and Ruthenium

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1969 The epS aration and Determination of Osmium and Ruthenium. Harry Edward Moseley Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Moseley, Harry Edward, "The eS paration and Determination of Osmium and Ruthenium." (1969). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1559. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1559 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ThU dissertation has been 69-17,123 microfilmsd exactly as received MOSELEY, Harry Edward, 1929- THE SEPARATION AND DETERMINATION OF OSMIUM AND RUTHENIUM. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, PhJ>., 1969 Chemistry, analytical University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan THE SEPARATION AND DETERMINATION OF OSMIUM AND RUTHENIUM A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Chemistry Harry Edward Moseley B.S., Lpuisiana State University, 1951 M.S., Louisiana State University, 1952 J anuary, 1969 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Thanks are due to Dr. Eugene W. Berg under whose direction this work was performed, to Dr. A. D. Shendrikar for his help in the tracer studies, and to Mr. J. H. R. Streiffer for his help in writing the com puter program. -

Cavendish the Experimental Life

Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge Series Editors Ian T. Baldwin, Gerd Graßhoff, Jürgen Renn, Dagmar Schäfer, Robert Schlögl, Bernard F. Schutz Edition Open Access Development Team Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Klaus Thoden, Dirk Wintergrün. The Edition Open Access (EOA) platform was founded to bring together publi- cation initiatives seeking to disseminate the results of scholarly work in a format that combines traditional publications with the digital medium. It currently hosts the open-access publications of the “Max Planck Research Library for the History and Development of Knowledge” (MPRL) and “Edition Open Sources” (EOS). EOA is open to host other open access initiatives similar in conception and spirit, in accordance with the Berlin Declaration on Open Access to Knowledge in the sciences and humanities, which was launched by the Max Planck Society in 2003. By combining the advantages of traditional publications and the digital medium, the platform offers a new way of publishing research and of studying historical topics or current issues in relation to primary materials that are otherwise not easily available. The volumes are available both as printed books and as online open access publications. They are directed at scholars and students of various disciplines, and at a broader public interested in how science shapes our world. Cavendish The Experimental Life Revised Second Edition Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach Studies 7 Studies 7 Communicated by Jed Z. Buchwald Editorial Team: Lindy Divarci, Georg Pflanz, Bendix Düker, Caroline Frank, Beatrice Hermann, Beatrice Hilke Image Processing: Digitization Group of the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover Image: Chemical Laboratory. -

Back Matter (PDF)

INDEX TO THE PHILOSOPHICAL TRANSACTIONS (A) FOR THE YEAR 1894. A. Arc spectrum of electrolytic ,iron on the photographic, 983 (see Lockyer). B. Bakerian L ecture.—On the Relations between the Viscosity (Internal 1 riction) of Liquids and then Chemical Nature, 397 (see T iiorpe and R odger). Bessemer process, the spectroscopic phenomena and thermo-chemistry of the, 1041 IIarimo). C. Capstick (J. W.). On the Ratio of the Specific Heats of the Paraffins, and their Monohalogei.. Derivatives, 1. Carbon dioxide, on the specific heat of, at constant volume, 943 (sec ). Carbon dioxide, the specific heat of, as a function of temperatuie, ddl (mo I j . , , Crystals, an instrument of precision for producing monochromatic light of any desire. ua\e- eng », * its use in the investigation of the optical properties of, did (see it MDCCCXCIV.— A. ^ <'rystals of artificial preparations, an instrument for grinding section-plates and prisms of, 887 (see Tutton). Cubic surface, on a special form of the general equation of a, and on a diagram representing the twenty- seven lines on the surface, 37 (see Taylor). •Cables, on plane, 247 (see Scott). D. D unkeelky (S.). On the Whirling and Vibration of Shafts, 279. Dynamical theory of the electric and luminifei’ous medium, a, 719 (see Larmor). E. Eclipse of the sun, April 16, 1893, preliminary report on the results obtained with the prismatic cameras during the total, 711 (see Lockyer). Electric and luminiferous medium, a dynamical theory of the, 719 (see Larmor). Electrolytic iron, on the photographic arc spectrum of, 983 (see Lockyer). Equation of the general cubic surface, 37 (see Taylor). -

RBRC-32 BNL-6835.4 PARITY ODD BUBBLES in HOT QCD D. KHARZEEV in This ~A~Er We Give a Pedawwicalintroduction~0 Recent Work Of

RBRC-32 BNL-6835.4 PARITY ODD BUBBLES IN HOT QCD D. KHARZEEV RIKEN BNL Research Center, Br$ookhauenNational Laboratory, . Upton, New York 11973-5000, USA R.D. PISARSKI Department of Physics, Brookhaven National Laboratoy, Upton, New York 11973-5000, USA M.H.G. TYTGAT Seruice de Physique Th&orique, (7P 225, Uniuersitc4Libre de Bruzelles, B[ud. du !t%iomphe, 1050 Bruxelles, Belgium We consider the topological susceptibility for an SU(N) gauge theory in the limit of a large number of colors, N + m. At nonzero temperature, the behavior of the topological susceptibility depends upon the order of the reconfining phrrse transition. The meet interesting possibility is if the reconfining transition, at T = Td, is of second order. Then we argue that Witten’s relation implies that the topological suscepti~lfity vanishes in a calculable fdion at Td. Ae noted by Witten, this implies that for sufficiently light quark messes, metaetable etates which act like regions of nonzero O — parity odd bubbles — can arise at temperatures just below Td. Experimentally, parity odd bubbles have dramatic signature% the rI’ meson, and especially the q meson, become light, and are copiously produced. Further, in parity odd bubbles, processes which are normally forbidden, such as q + rr”ro, are allowed. The most direct way to detect parity violation is by measuring a parity odd global seymmetry for charged pions, which we define. 1 Introduction In this .-~a~er we give a Pedawwicalintroduction~0 recent work of ours? We I consider an SU(IV) gau”ge t~e~ry in the limit of a large number of colors, N + co, This is, of course, a familiar limit? We use the large N expansion I to investigate the behavior of the theory at nonzero temperature, especially for the topological susceptibility. -

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town Cl740-Cl820

The Economic Development of Sheffield and the Growth of the Town cl740-cl820 Neville Flavell PhD The Division of Adult Continuing Education University of Sheffield February 1996 Volume One THE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF SHEFFIELD AND THE GROWTH OF THE TOWN cl740-c 1820 Neville Flavell February 1996 SUMMARY In the early eighteenth century Sheffield was a modest industrial town with an established reputation for cutlery and hardware. It was, however, far inland, off the main highway network and twenty miles from the nearest navigation. One might say that with those disadvantages its future looked distinctly unpromising. A century later, Sheffield was a maker of plated goods and silverware of international repute, was en route to world supremacy in steel, and had already become the world's greatest producer of cutlery and edge tools. How did it happen? Internal economies of scale vastly outweighed deficiencies. Skills, innovations and discoveries, entrepreneurs, investment, key local resources (water power, coal, wood and iron), and a rapidly growing labour force swelled largely by immigrants from the region were paramount. Each of these, together with external credit, improved transport and ever-widening markets, played a significant part in the town's metamorphosis. Economic and population growth were accompanied by a series of urban developments which first pushed outward the existing boundaries. Considerable infill of gardens and orchards followed, with further peripheral expansion overspilling into adjacent townships. New industrial, commercial and civic building, most of it within the central area, reinforced this second phase. A period of retrenchment coincided with the French and Napoleonic wars, before a renewed surge of construction restored the impetus. -

Hexagon Fall

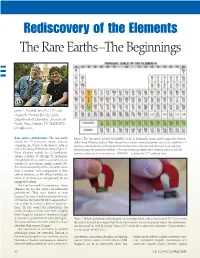

Redis co very of the Elements The Rare Earth s–The Beginnings I I I James L. Marshall, Beta Eta 1971 , and Virginia R. Marshall, Beta Eta 2003 , Department of Chemistry, University of North Texas, Denton, TX 76203-5070, [email protected] 1 Rare earths —introduction. The rare earths Figure 1. The “rare earths” are defined by IUPAC as the 15 lanthanides (green) and the upper two elements include the 17 chemically similar elements of the Group III family (yellow). These elements have similar chemical properties and all can exhibit the +3 occupying the f-block of the Periodic Table as oxidation state by the loss of the highest three electrons (two s electrons and either a d or an f electron, well as the Group III chemical family (Figure 1). depending upon the particular element). A few rare earths can exhibit other oxidation states as well; for These elements include the 15 lanthanides example, cerium can lose four electrons —4f15d 16s 2—to attain the Ce +4 oxidation state. (atomic numbers 57 through 71, lanthanum through lutetium), as well as scandium (atomic number 21) and yttrium (atomic number 39). The chemical similarity of the rare earths arises from a common ionic configuration of their valence electrons, as the filling f-orbitals are buried in an inner core and generally do not engage in bonding. The term “rare earths” is a misnome r—these elements are not rare (except for radioactive promethium). They were named as such because they were found in unusual minerals, and because they were difficult to separate from one another by ordinary chemical manipula - tions.