ISAS Insights No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kejriwal-Ki-Kahani-Chitron-Ki-Zabani

केजरवाल के कम से परेशां कसी आम आदमी ने उनके ीमखु पर याह फेकं. आम आदमी पाट क सभाओं म# काय$कता$ओं से &यादा 'ेस वाले होते ह). क*मीर +वरोधी और भारत देश को खं.डत करने वाले संगठन2 का साथ इनको श5ु से 6मलता रहा है. Shimrit lee वो म8हला है िजसके ऊपर शक है क वो सी आई ए एज#ट है. इस म8हला ने केजरवाल क एन जी ओ म# कु छ 8दन रह कर भारत के लोकतं> पर शोध कया था. िजंदल ?पु के असल मा6लक एस िजंदल के साथ अAना और केजरवाल. िजंदल ?पु कोयला घोटाले म# शा6मल है. ये है इनके सेकु लCर&म का असल 5प. Dया कभी इAह# साध ू संत2 के साथ भी देखा गया है. मिलमु वोट2 के 6लए ये कु छ भी कर#गे. दंगे के आरो+पय2 तक को गले लगाय#गे. योगेAF यादव पहले कां?ेस के 6लए काम कया करते थे. ये पहले (एन ए सी ) िजसक अIयJ सोKनया गाँधी ह) के 6लए भी काम कया करते थे. भारत के लोकसभा चनावु म# +वदे6शय2 का आम आदमी पाट के Nवारा दखल. ये कोई भी सकते ह). सी आई ए एज#ट भी. केजरवाल मलायमु 6संह के भी बाप ह). उAह# कु छ 6सरफरे 8हAदओंु का वोट पDका है और बाक का 8हसाब मिलमु वोट से चल जायेगा. -

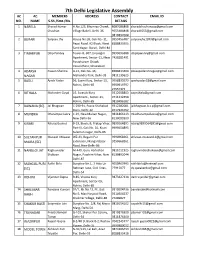

List of MLA Contact Details

7th Delhi Legislative Assembly AC AC MEMBERS ADDRESS CONTACT EMAIL ID NO. NAME S.Sh./Smt./Ms. DETAILS 1 NARELA Sharad Kumar H.No.123, Bhumiya Chowk, 8687686868 [email protected] Chauhan Village Bakoli, Delhi-36 9555484848 [email protected] 9818892004 2 BURARI Sanjeev Jha House No.09, Gali No.-11, 9953456787 [email protected] Pepsi Road, A2 Block, West 8588833505 Sant Nagar, Burari, Delhi-84 3 TIMARPUR Dilip Pandey Tower-B, 607, Dronagiri 9999696388 [email protected] Apartment, Sector-11, Near 7428281491 Parashuram Chowk Vasundhara, Ghaziabad 4 ADARSH Pawan Sharma A-13, Gali No.-36, 8588833404 [email protected] NAGAR Mahendra Park, Delhi-33 9811139625 5 BADLI Ajesh Yadav 56, Laxmi Kunj, Sector-13, 9958833979 [email protected] Rohini, Delhi-85 9990919797 27557375 6 RITHALA Mohinder Goyal 19, Swastik Kunj 9312658803 [email protected] Apartment., Sector-13, 9711332458 Rohini, Delhi-85 9810496182 7 BAWANA (SC) Jai Bhagwan C-290-91, Pucca Shahabad 9312282081 [email protected] Dairy, Delhi-42 9717921052 8 MUNDKA Dharampal Lakra C-29, New Multan Nagar, 9811866113 [email protected] New Delhi-56 8130099300 9 KIRARI Rituraj Govind B-19, Block,-B, Pratap Vihar, 9899564895 [email protected] Part-III, Gali No. 10, Kirari 9999654895 Suleman nagar, Delhi-86 10 SULTANPUR Mukesh Ahlawat WZ-43, Begum Pur 9990968261 [email protected] MAJRA (SC) Extension, Mangal Bazar 9250668261 Road, New Delhi-86 11 NANGLOI JAT Raghuvinder M-449, Guru Harkishan 9811011925 [email protected] -

“The Idea of India Needs to Be Recreated”

#GreatIndiaDebate ABOUT THE EVENT Great India Debate 2.0 brings together 8 of India’s most powerful and articulate intellectuals, who will debate, in a structured format, a motion that is of great relevance today to millions of Indians #GreatIndiaDebate DEBATE TOPIC: “INDIA’s Growth Story Cannot Survive Another Era of Coalition Politics” #GreatIndiaDebate FACT FILE Program: Debate/Panel Duration: 6 PM - 8 PM (Followed By Dinner) Number of Delegates: 250-300 Venue: ITC Maurya, New Delhi Date: 27 February, 2019 Format: Traditional Debate with 5 Speakers Supporting & 5 Opposing the Motion #GreatIndiaDebate SPEAKERS Swapan Dasgupta Sunil Alagh Shazia Ilmi Member of Parliament Former Managing Official Spokesperson Rajya Sabha Director and Chief Aam Aadmi Party Executive Officer, Britannia Industries #GreatIndiaDebate SPEAKERS Arif Mohammad Khan Gurcharan Das Former Cabinet Minister Author, Commentator, The Union of India Thought Leader #GreatIndiaDebate SPEAKERS Kiran Karnik Sanjay Jha Raghav Chadha Former President National Spokesperson Member NASSCOM Indian National Congress Political Affairs Committee Aam Aadmi Party #GreatIndiaDebate CONSULTANT MODERATOR Priyanka Chaturvedi Sonia Singh Bhuvan Lall National Spokesperson Editorial Director Film Producer & Author Indian National Congress NDTV #GreatIndiaDebate LAST GREAT INDIA DEBATE SPEAKERS HARDEEP PURI Dr RAJIV KUMAR SWAPAN DASGUPTA FRANÇOIS GAUTIER Minister of State Vice Chairman Member of Parliament Writer & Journalist Housing & Urban Affairs NITI Aayog #GreatIndiaDebate LAST GREAT INDIA DEBATE SPEAKERS MANI SHANKAR MANISH TEWARI PAVAN VARMA MAROOF RAZA AIYAR Former Indian Former Member of Publisher Indian Diplomat diplomat turned Parliament Salute Magazine turned Politician Politician Rajya Sabha #GreatIndiaDebate 5 REASONS TO PARTCIPATE 1) Exclusive Debate by 8 of India’s most Powerful and Articulate Intellects. -

Delhi Assembly Election 2020 Constituencies

www.gradeup.co 1 www.gradeup.co List of Constituencies, Winners & Runners-up - Download PDF Assembly Winner Runner Up Constituency Margin of Votes Name Candidate Party Candidate Party Neel Daman Narela Sharad Kumar AAP BJP 17429 Khatri Burari Sanjeev Jha AAP Shailendra Kumar JD(U) 88158 Surinder Pal Timarpur Dilip Pandey AAP BJP 24144 Singh Adarsh Nagar Pawan Sharma AAP Raj Kumar Bhatia BJP 1589 Vijay Kumar Badli Ajesh Yadav AAP BJP 29123 Bhagat Manish Rithala Mohinder Goyal AAP BJP 13873 Chaudhary Bawana(SC) Jai Bhagwan AAP Ravinder Kumar BJP 11526 Mundka Dharampla Lakra AAP Azad Singh BJP 19158 Kirari Rituraj Govind AAP Anil Jha Vats BJP 5654 Sultan Pur Mukesh Kumar Ram Chander AAP BJP 48052 Majra(SC) Ahlawat Chawriya Raghuvinder Nangloi Jat AAP Suman Lata BJP 11624 Shokeen Karam Singh Mangol Puri(SC) Rakhi Birla AAP BJP 30116 Karma Rajesh Nama Rohini Vijender Gupta BJP AAP 12648 Bansiwala Shalimar Bagh Bandana Kumari AAP Rekha Gupta BJP 3440 Satyendra Kumar Shakur Basti AAP Dr. S. C. Vats BJP 7592 Jain Tri Nagar Preeti Tomar AAP Tilak Ram Gupta BJP 10710 Dr. Mahender Wazirpur Rajesh Gupta AAP BJP 11690 Nagpal Akhilesh Pati Model Town AAP Kapil Mishra BJP 11133 Tripathi Sadar Bazar Som Dutt AAP Jai Parkash BJP 25644 Parlad Singh Suman Kumar Chandni Chowk AAP BJP 29584 Sawhney Gupta Matia Mahal Shoaib Iqbal AAP Ravinder Gupta BJP 50241 Ballimaran Imran Hussain AAP Lata BJP 36172 2 www.gradeup.co Assembly Winner Runner Up Constituency Margin of Votes Name Candidate Party Candidate Party Yogender Karol Bagh(SC) Vishesh Ravi AAP BJP 31760 -

Elixir Journal

50235 Anupama Verma / Elixir Social Studies 116 (2018) 50235-50239 Available online at www.elixirpublishers.com (Elixir International Journal) Social Studies Elixir Social Studies 116 (2018) 50235-50239 Female Participation in Delhi Assembly Election 2015 Anupama Verma Assistant Professor, Department of Geography, Shaheed Bhagat Singh (Eve) College, University of Delhi, Delhi. ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article history: The term 'political participation' has a broad inclusive meaning. It is not only related to Received: 07 February 2018; 'Right to Vote', but simultaneously relates to participation in: decision making process, Received in revised form: political activism, political consciousness, etc. Political activism and voting are the 12 March 2018; strongest areas of women's political participation. Participation in decision-making Accepted: 23 March 2018; process is the real tool of women empowerment. Women are going to play a crucial role in selecting their political representative. Politicos can no longer ignore these sections of Keywords the society as a large number of youth and women are getting enrolled their names in Political participation, voters list since 2008 assembly election. As per the electoral rolls (2015), a total of 1.33 Women empowerment, crore people are eligible to vote in Delhi of which over 72 lakh are men and around 59 Political parties, lakh are women. Out of the 673 candidates in fray for Delhi Assembly election 2015, Turnout, only 66 are women. While there were assurances galore on women‟s safety in the Voters list. national capital ahead of the polls, the number of tickets given to women candidates by the three leading political parties was in sharp contrast to the population of women voters in Delhi. -

Press Release Delhi Assembly Elections, 2015 Analysis of Criminal

30th January, 2015 Press Release Delhi Assembly Elections, 2015 Analysis of Criminal Background, Financial, Education, Gender and other details of Candidates Association for Democratic Reforms T-95A, C.L. House, 1st Floor, Near Gulmohar Commercial Complex Gautam Nagar, New Delhi-110 049 Phone: +91-011-4165-4200 Fax : +91-11-46094248 Email : [email protected] To report any electoral violations and malpractices during elections download the Election Watch Reporter (Android App) https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.webrosoft.election_watch_reporter Contents DELHI ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS, 2015 ............................................................................................................. 1 ANALYSIS OF CRIMINAL BACKGROUND, FINANCIAL, EDUCATION, GENDER AND OTHER DETAILS OF CANDIDATES .............................................................................................................................. 1 SUMMARY AND HIGHLIGHTS ........................................................................................................................ 3 CRIMINAL BACKGROUND .....................................................................................................................................3 FINANCIAL BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................................5 OTHER BACKGROUND DETAILS ............................................................................................................................8 ANALYSIS BASED -

Press Release Delhi Assembly Elections, 2015 Analysis of Financial Details of Re-Contesting Mlas Association for Democratic Refo

30th January, 2015 Press Release Delhi Assembly Elections, 2015 Analysis of Financial Details of Re-contesting MLAs Association for Democratic Reforms T-95A, C.L. House, 1st Floor, Near Gulmohar Commercial Complex Gautam Nagar, New Delhi-110 049 Phone: +91-011-4165-4200 Fax : +91-11-46094248 Email : [email protected] To report any electoral violations and malpractices during elections download the Election Watch Reporter (Android App) https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.webrosoft.election_watch_reporter Data in this Kit is presented in good faith, with an intention to inform voters.Candidates' affidavit with nomination papers is the source of this analysis. Website:-www.adrindia.org, www.myneta.info Page 1 of 10 Delhi Election Watch (DEW) and Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) have analysed the self-sworn affidavits of 62 re-contesting MLAs contesting in Delhi Assembly Elections in 2015. Executive Summary MLAs Contesting Again: Delhi Election Watch (DEW) and Association for Democratic Reforms (ADR) have analyzed the affidavits of 62 outgoing MLAs who are contesting again in the 2015 Delhi Assembly Elections. Average Assets in 2013 Elections: The average assets of these 62 re-contesting MLAs fielded by various parties including independents in 2013 were Rs 11.66 crores (Rs. 11,66,16,836.83) Average Assets in 2015 Elections: The average assets of these 62 re-contesting MLAs in 2015 are Rs 11.48 crores (Rs. 11,48,39,470.93). Average Asset change from 2013 to 2015: The average assets of these 62 re- contesting MLAs, between the Delhi Elections of 2013 and 2015 decreased by Rs. -

Mla Ratings 2019

A comprehensive & objective rating of the Elected Representatives’ performance DELHI MLA RATINGS 2019 he´pee SkeÀ Dehe#eheeleer mebmLeeve nw pees 1999 mes GÊejoe³eer Meemeve keÀes me#ece yeveeves keÀer efoMee ceW keÀece keÀj jner nw~ he´pee veeieefjkeÀeW keÀes peevekeÀejer Deewj heefjhe´s#³e he´oeve keÀj Meemeve‑efJeefOe ceW Yeeie uesves kesÀ efueS MeefÊeÀ he´oeve keÀjleer nw leeefkeÀ Jes cele‑hesìer lekeÀ ner meerefcele ve jns Deewj jepeveereflekeÀ ªhe mes meef¬eÀ³e Deewj meeqcceefuele nes mekeWÀ~ ³en J³eehekeÀ MeesOekeÀe³e& keÀjleer nw Deewj veeieefjkeÀeW keÀer mecem³eeDeeW keÀes Gpeeiej keÀjleer nw leeefkeÀ Jes GmekesÀ he´efle peeieªkeÀ nes mekeWÀ, Deewj mejkeÀejer Deewj efveJee&ef®ele he´efleefveefOe³eeW kesÀ keÀece keÀes ueeceyebo keÀj mekeWÀ~ mecem³ee he´pee keÀer he´efleef¬eÀ³ee he´pee keÀe ceevevee nw efkeÀ De®íer Meemeve‑efJeefOe keÀer he´pee DeeBkeÀæ[eW hej DeeOeeefjle MeesOekeÀe³e& keÀjleer nw keÀceer kesÀ efueS DeveefYe%e Deewj Deueie‑Leueie heæ[s Deewj veeieefjkeÀeW, ceeref[³ee, Deewj mejkeÀejer he´Meemeve efveJee&ef®ele he´efleefveefOe Deewj he´Meemeve ef]peccesoej keÀes peve mecem³eeDeeW mes mecyebefOele peevekeÀejer he´oeve nQ, ve efkeÀ ceewpetoe mece³e kesÀ leb$e ³ee veerefle³eeB~ keÀjleer nw Deewj ®egves ieS he´efleefveefOe³eeW kesÀ meeLe FmekesÀ DeefleefjÊeÀ, veeieefjkeÀeW Deewj mLeeveer³e efceuekeÀj GvekeÀer keÀe³e&‑he´Ceeefue³eeW ceW DekegÀMeuelee mejkeÀej kesÀ yeer®e he´YeeJeMeeueer Jeeo‑J³eJnej keÀer hen®eeve keÀjves Deewj Gme keÀes otj keÀjves, met®evee keÀes megefJeOeepevekeÀ yeveeves kesÀ GhekeÀjCeeW keÀe Yeer -

Primo.Qxd (Page 1)

THURSDAY, APRIL 10, 2014 (PAGE 4) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU Mahayagyas performed to Bodies of missing councilor’s Stage set for 3rd phase of LS CONDOLENCE The Ganesh Mandir Sabha Ganeshpora culminate Navratra Puja poll covering 11 States, 3 UTs Pahalgam condole the sad demise of Sh Makhan Lal Bhat S/o Late Sh Swaroop Nath Bhat original- Excelsior Correspondent attended by concerned DDC, son, associate recovered NEW DELHI, Apr 9: Lok Dal (RLD) chief Ajit Singh ly resident of Ganeshpora Pahalgam. He was a pitted against former Mumbai Brigadier and various Defence Excelsior Correspondent DL6CH 1158, SSP added. The stage is now set for the man full of good qualities. May God rest his soul in JAMMU, Apr 9: To culmi- Police Commissioner Satyapal peace and give strength to bereaved family to bear Personnel and Heads of various The youth were stopped by first substantial round of polling in nate Navratra Puja, Mahayagyas offices. KARGIL, Apr 9: Sonamarg Singh (BJP) in Baghpat, recent the irreparable loss. the Drass police, but they made the Lok Sabha elections tomorrow From : were performed at various police recovered the bodies of RLD entrant actress-politician Nine-day long Navratra Puja an excuse of going to Machovi, involving nearly 11 crore voters in 1. President ashrams in Srinagar and Jammu, the missing LAHDC councilor’s Jaya Prada (Bijnor), film stars culminated with a Mahayagya at he said. 92 seats spread across 11 States, 2. Secretary Sh Makhan Lal Bhat yesterday. son and his associate at Sarbal Nagma (Meerut) and Raj Babbar 3. Members Sharika Peeth Sanastha, Subash Due to cold weather condi- including Delhi and the national Shri Rama Krishna and Milagarh areas in district (Ghaziabad-both Cong), AAP’s Nagar in Jammu. -

Location Identified by Hon'ble Member of Legislative Assembly, Delhi For

Location identified by Hon'ble Member of Legislative Assembly, Delhi for facilitating distribution of emergency relief coupon S.N Constituency Constituency Candidate Contact Helpdesk Office Address o Number Name Number 1 1 Narela Sharad Kumar 8687686868 H No 123, Bhumiya Chowk, Village Chauhan Bakoli, Delhi-36 2 2 Burari Sanjeev Jha 9953456787 Khasra no 711 Opposite Syndicate Bank Main 100 ft Road Burari, Delhi 3 3 Timarpur Dilip Kumar 7428281491 Delhi Jal Board Office Mukharjee Pandey Nagar Area, Mukharjee Nagar , Delhi 4 4 Adarsh Nagar Pawan Sharma 8588833404 A-13, Gali No.-36, Mahendra Park, Delhi 5 5 Badli Ajesh Yadav 9958833979 Shop No 9 10 main GT karnal road libas pur near jagdamba motors, Delhi 6 6 Rithala Mohinder Goyal 9312658803 MLA Office thane ki tanki ke peche sector 1 avantika rohini, Delhi 7 7 Bawana (Sc) Jai Bhagwan 9312282081 C 25/21 Shabhad Dairy Near Nirankari Bhawan, Delhi 8 8 Mundka Dharampal Lakra 9811866113 khasra no 562/2/3 Main Rohtak Road, Village Munka, Delhi 9 9 Kirari Rituraj Govind 9899564895 MLA Office Near Nithari Puliya Kirari, Delhi 10 10 Sultanpur Majra Mukesh Ahlawat 9990968261 AB Extension 30 Sultanpuri Delhi 11 11 Nangloi Jat Raghuvinder 9811011925 RZ-B 232 Main 50ft road Nihal Vihar, Shokeen Nangloi, Delhi-110041 12 12 Mangol Puri Rakhi Birla 9650907995 S 622-623 Mangolpuri Near Sanjay Gandhi Hospital, Delhi 13 13 Rohini Virender 9873427234 Maharana Pratap Community Gupta Center, Sampurna Kendra, Rajapur Village, Sec-9, Rohini 14 14 Shalimar Bagh Bandana Kumari 9310504236 Plot no 102 Gali no 9 shalimar -

Downloaded for Personal Non‐Commercial Research Or Study, Without Prior Permission Or Charge

Muraleedharan, Sruthi (2019) Symbolic encounters : identity, performativity and democratic subjectivity in contemporary India. PhD thesis. SOAS University of London. http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/30897 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Symbolic Encounters: Identity, Performativity and Democratic Subjectivity in Contemporary India Sruthi Muraleedharan Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD in Politics and International Studies 2019 Department of Politics and International Studies Faculty of Law and Social Sciences SOAS, University of London Abstract This thesis focuses on symbolic politics as ‘meaning-making’ and a ‘co- constitutive’ form of representation. It seeks to analyze subject formation in the context of symbolic political mobilizations in contemporary India. By symbolic politics, I mean political rituals, cultural symbols, commemorative memorials and spectacular performances. Through deploying Bourdieusian idea of symbolic power and Butler’s framework of performativity and subject formation, this thesis contributes to rethinking of the relationship between symbolic politics and subject formation. -

DELHI ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS 2015 Party-Wise Winning Candidates

DELHI ASSEMBLY ELECTIONS 2015 Party-wise Winning Candidates Constituency Const. No. Winning Candidate Leading Party Runner-up Candidate Trailing Party Margin ADARSH NAGAR 4 PAWAN KUMAR SHARMA Aam Aadmi Party RAM KISHAN SINGHAL Bharatiya Janata Party 20741 AMBEDKAR NAGAR 48 AJAY DUTT Aam Aadmi Party ASHOK KUMAR Bharatiya Janata Party 42460 BABARPUR 67 GOPAL RAI Aam Aadmi Party NARESH GAUR Bharatiya Janata Party 35488 BADARPUR 53 NARAYAN DUTT SHARMA Aam Aadmi Party RAMVIR SINGH BIDHURI Bharatiya Janata Party 47583 BADLI 5 AJESH YADAV Aam Aadmi Party DEVENDER YADAV Indian National Congress 35376 BALLIMARAN 22 IMRAN HUSSAIN Aam Aadmi Party SHAYAM LAL MORWAL Bharatiya Janata Party 33877 BAWANA 7 VED PARKASH Aam Aadmi Party GUGAN SINGH Bharatiya Janata Party 50023 BIJWASAN 36 COL DEVINDER SEHRAWAT Aam Aadmi Party SAT PRAKASH RANA Bharatiya Janata Party 19536 BURARI 2 SANJEEV JHA Aam Aadmi Party GOPAL JHA Bharatiya Janata Party 67950 CHANDNI CHOWK 20 ALKA LAMBA Aam Aadmi Party SUMAN KUMAR GUPTA Bharatiya Janata Party 18287 CHHATARPUR 46 KARTAR SINGH TANWAR Aam Aadmi Party BRAHM SINGH TANWAR Bharatiya Janata Party 22240 DELHI CANTT 38 SURENDER SINGH Aam Aadmi Party KARAN SINGH TANWAR Bharatiya Janata Party 11198 DEOLI 47 PRAKASH Aam Aadmi Party ARVIND KUMAR Bharatiya Janata Party 63937 DWARKA 33 ADARSH SHASTRI Aam Aadmi Party PARDUYMN RAJPUT Bharatiya Janata Party 39366 GANDHI NAGAR 61 ANIL KUMAR BAJPAI Aam Aadmi Party JITENDER Bharatiya Janata Party 7482 GHONDA 66 SHRI DUTT SHARMA Aam Aadmi Party SAHAB SINGH CHAUHAN Bharatiya Janata Party 8093 GOKALPUR 68 FATEH SINGH Aam Aadmi Party RANJEET SINGH Bharatiya Janata Party 31968 GREATER KAILASH 50 SAURABH BHARADWAJ Aam Aadmi Party RAKESH KUMAR GULLAIYA Bharatiya Janata Party 14583 HARI NAGAR 28 JAGDEEP SINGH Aam Aadmi Party AVTAR SINGH HIT Bharatiya Janata Party 26496 JANAKPURI 30 RAJESH RISHI Aam Aadmi Party PROF.