International Air Services Inquiry Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Annual Report 2004/05

ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES Annual Report 2004-05 WWW.ETHIOPIANAIRLINES.COM ANNUAL REPORT 2004-05 building CONTENTS on the FUTURE Management Board of Ethiopian Airlines .................................. 2 CEO’s Message............................................................................................. 3 Ethiopian Airlines Management Team ......................................... 4 Embarking on a long-range reform I. Investing for the future Continent .................................... 5 II. Continuous Change .............................................................. 5 III. Operations Review ............................................................... 5 IV. Measures to Enhance Profitability .................................. 7 V. Human Resource Development ....................................... 10 VI. Fleet Planning and Financing .......................................... 11 VII. Information Systems .......................................................... 11 VIII. Tourism Promotion ............................................................ 11 IX. Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Measures ....... 12 Finance ............................................................................................................. 13 Auditors Report and Financial Statements ................................ 22 Domestic Route Map .............................................................................. 40 Ethiopian Airlines Offices ...................................................................... 41 International Route Map ...................................................................... -

Qantas' Future As a Strong National Carrier Supporting Jobs in Australia

Coalition Senators' Dissenting Report 1.1 As a nation we are increasingly reliant on efficient, inexpensive and convenient aviation services. This is hardly surprising when you consider that our population is spread over such a vast land mass. 1.2 Aviation is a dynamic industry that has faced many challenges over the past decades since the introduction of the QSA in 1992. In Australia the market is highly competitive and presently capacity is saturated which has resulted in lower yields and affected the profitability of our carriers. 1.3 From a passenger’s perspective, the competitive tension between Qantas and Virgin Australia has resulted in a high quality product being delivered at a lower price with increased destinations and often with more convenient schedules. 1.4 Both Virgin Australia and Qantas are clearly excellent Australian airlines which contribute significantly to the economy, regional communities and tourism and have both shown a willingness to assist Australians in times of crisis. 1.5 Airlines also operate in an environment of increasing higher fuel costs, a relatively high Australian dollar compared to previous decades and significant capital expenditure requirements in an effort to operate the most modern and fuel efficient aircraft fleets. 1.6 Additionally, the carbon tax has added significantly to the costs of operating Australian domestic airlines. In the 2013-14 financial year the carbon tax drove up operating expenses at Qantas by $106 million and $48 million at Virgin Australia. It also cost Regional Express (Rex) $2.4 million. 1.7 The cumulative effect of all of these factors has led to an environment where both Australia’s major domestic carriers have announced first half losses; Qantas of $252 million and Virgin Australia of $84 million. -

My Personal Callsign List This List Was Not Designed for Publication However Due to Several Requests I Have Decided to Make It Downloadable

- www.egxwinfogroup.co.uk - The EGXWinfo Group of Twitter Accounts - @EGXWinfoGroup on Twitter - My Personal Callsign List This list was not designed for publication however due to several requests I have decided to make it downloadable. It is a mixture of listed callsigns and logged callsigns so some have numbers after the callsign as they were heard. Use CTL+F in Adobe Reader to search for your callsign Callsign ICAO/PRI IATA Unit Type Based Country Type ABG AAB W9 Abelag Aviation Belgium Civil ARMYAIR AAC Army Air Corps United Kingdom Civil AgustaWestland Lynx AH.9A/AW159 Wildcat ARMYAIR 200# AAC 2Regt | AAC AH.1 AAC Middle Wallop United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 300# AAC 3Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 400# AAC 4Regt | AAC AgustaWestland AH-64 Apache AH.1 RAF Wattisham United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 500# AAC 5Regt AAC/RAF Britten-Norman Islander/Defender JHCFS Aldergrove United Kingdom Military ARMYAIR 600# AAC 657Sqn | JSFAW | AAC Various RAF Odiham United Kingdom Military Ambassador AAD Mann Air Ltd United Kingdom Civil AIGLE AZUR AAF ZI Aigle Azur France Civil ATLANTIC AAG KI Air Atlantique United Kingdom Civil ATLANTIC AAG Atlantic Flight Training United Kingdom Civil ALOHA AAH KH Aloha Air Cargo United States Civil BOREALIS AAI Air Aurora United States Civil ALFA SUDAN AAJ Alfa Airlines Sudan Civil ALASKA ISLAND AAK Alaska Island Air United States Civil AMERICAN AAL AA American Airlines United States Civil AM CORP AAM Aviation Management Corporation United States Civil -

IT Travel Group Has Operated As a HOST TRAVEL AGENCY Since June of 1989

Dear Travel Entrepreneur: IT Travel Group has operated as a HOST TRAVEL AGENCY since June of 1989. The management of IT Travel Group would like to share with you the following information about our unique support system offered Independent Contractors (IC) via our HOST AGENCY operating divisions: A Host Agency’s responsibilities include holding travel industry conference appointments with Domestic (ARC) and International (IATAN) airlines for ticket issuance capabilities, and Cruise line appointments (CLIA) for earning commissions from cruise sales. International Tours of Houston (ITH) is bonded and holds conference appointments with the following travel industry organizations: ARC – Airline Reporting Corporation – This conference appoints travel agent business entities on behalf of the Domestic Air Lines and controls the issuance of ticket stock and payment for tickets issued by travel agencies. Minimum appointment criteria: $20,000 Surety Bond or LOC and agent qualifier with 18 to 24 months agency work experience and Certified ARC Specialist (CAS) certificate. IATAN – International Airline Travel Agency Network - This conference also appoints travel agent entities for the International Air Carriers and administers the travel agent eligibility list for reduced rate travel benefits. CLIA – Cruise Lines International Association – This conference represents the majority of the world’s cruise lines and administers the appointment process for travel entities to earn commission from their cruise sales. ITH and staff hold individual and Host -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

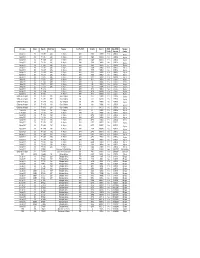

Final AFI RVSM Approvals 05 June 08

Mfr & Type Variant Reg. No. Build Year Operator Acft Op ICAO Serial No Mode S RVSM Date RVSM Operator Yes/No Approval Country Boeing 737 800 7T - VJK 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30203 0A0019 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJL 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30204 0A001A Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJM 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30205 0A001B Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJN 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30206 0A0020 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJQ 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30207 0A0021 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJP 2001 Air Algérie DAH 30208 0A0022 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJR 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30545 0A0025 Yes 01/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJS 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30210 0A0026 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJT 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30546 0A0027 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJU 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30211 0A0028 Yes 06/07/02 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJV 2005 Air Algérie DAH 0644 0A0044 Yes 31/01/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJW 2005 Air Algérie DAH 647 0A0045 Yes 05/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJY 2005 Air Algérie DAH 653 0A0047 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJX 2005 Air Algérie DAH 650 0A0046 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKA Air Algérie DAH 34164 0A0049 Yes 23/07/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKB Air Algérie DAH 34165 0A004A Yes 22/08/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKC Air Algérie DAH 34166 0A004B Yes 24/08/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP 7T - VPC 2001 Gouv of Algeria IGA 1418 0A4009 Yes 27/07/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP -

Freedoms of the Air” Startupboeing

International Traffic Rights “The Freedoms of the Air” StartupBoeing The Freedoms of the Air are international commercial aviation agreements (traffic rights) that grant a country's airline(s) the privilege to enter and land in another country's airspace. They were formulated in 1944 at an international gathering held in Chicago (known as the Chicago Convention) to establish uniformity in world air commerce. There are generally considered to be nine freedoms of the air. Most nations of the world exchange first and second freedoms through the International Air Services Transit Agreement. The other freedoms, when available, are usually established between countries in bilateral or multilateral air services agreements. The third and fourth freedoms are always granted together. The eighth and ninth freedoms (cabotage) have been exchanged only in limited instances. (U.S. law currently prohibits cabotage operations.) Copyright © 2009 Boeing. All rights reserved. International Traffic Rights “The Freedoms of the Air” StartupBoeing First Freedom The negotiated right for an airline Country Country from country (A) to overfly another country’s (B) airspace. A B Home Country Second Freedom The right for a commercial aircraft from country (A) to land and refuel (commonly referred to Country Country as a technical stop) in another country (B). A B Home Technical Country Stop Third Freedom The right for an airline to deliver revenue passengers from the airline’s home country (A) to another Country Country country (B). A B Home Country Copyright © 2009 Boeing. All rights reserved. International Traffic Rights “The Freedoms of the Air” StartupBoeing Fourth Freedom The right for an airline to carry revenue passengers from another country (B) Country Country A B to the airline’s home country (A). -

Planning Global Meetings

Price $20.00 The ISMP Guide to Planning Global Meetings P.O. Box 879, Palm Springs, CA 92263 USA Tel: (877) 743-6802 Fax: (760) 327-5631 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ismp-assoc.org Table of Contents Issues of Today 3 Locations 7 Climate 9 Political Unrest 9 Language 10 Airports and Airline Rates 11 Hotel Rates 13 Crime/ Security 14 Incentives offered by Convention and Visitor Bureaus 14 Extra-curricular activity 15 Planning Global Meetings 3 Issues of Today Planning: we all know its importance, yet can we better apply training to ensure the success of a meeting? To guarantee success, harness technology to achieve meticulous planning. Create your own formulation of a planning document, which becomes your own blueprint to be employed time and again, in all your future planning. This methodology offers step-by-step checks, which over time, become automatic in the order of plan- ning you need. Involve all decision makers and support teams in regular updates to inform them of the progress of the meeting-planning documen- tation, based on a timetable of due dates, to meet internal dead- lines as well as external deadlines such as hotel closeout dates. This document could be indexed as separate chapters including the following: Brief: capturing venue, destination, meeting needs, profile and number of delegates, elementary components, preferred dates and budget, as well as historical data such as previous destinations and feedback and pro- grams. The client or decision maker whose core professional role is probably not a specialist meeting planner should endorse this document so that the planning and logistics teams, including the financial depart- ment, will be best prepared to adhere to the planning schedule, in particular the deadline dates and budget. -

CHAPTER 11: Civil Aviation Industry

CHAPTER 11: Civil Aviation Industry 11.1 AIR TRANSPORT The main objective of the decision was IN AFRICA the gradual liberalization of scheduled and non-scheduled intra-African air services, The poor state of land transport infrastructure abolishing limits on the capacity and and freight and passenger services in much frequency of international air services within of Africa appears to offer a promising Africa, liberalizing fares and universally opportunity for the further development of air granting traffi c rights up to the ”fi fth freedom transport services throughout the continent. At of the air.”2 Signatory states were obliged to this stage, the key policy issues for Zimbabwe ensure the fair opportunity to compete on a are the ways it can benefi t from the ongoing nondiscriminatory basis. A monitoring body liberalization of civil aviation within the was to supervise and implement the decision, continent called for in the Yamoussoukro and an African air transport executing agency Decision of 1999 and the actions it needs to was to ensure fair competition. Even though take in the decade ahead to ensure that the the decision was a pan-African agreement benefi ts of liberalization are realized. to which most African states are bound, the parties decided that it should be implemented 11.1.1 The Yamoussoukro Decision by separate regional economic organizations. The monitoring body has met only a few Over the past three decades, much of the times. Competition rules and arbitration world has moved from a strictly regulated air procedures are still pending. A recent World transport industry to a more liberalized one. -

Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit Into the World Trade Organization Ruwantissa I

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 61 | Issue 4 Article 2 1996 Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit into the World Trade Organization Ruwantissa I. R. Abeyratne Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Ruwantissa I. R. Abeyratne, Would Competition in Commercial Aviation Ever Fit into the World Trade Organization, 61 J. Air L. & Com. 793 (1996) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol61/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. WOULD COMPETITION IN COMMERCIAL AVIATION EVER FIT INTO THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION? RUWANTISSA I.R. ABEYRATNE* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ................................. 794 II. THE GENESIS OF AIR TRAFFIC RIGHTS ......... 795 A. TiH CHICAGO CONFERENCE ...................... 795 B. THE CHICAGO CONVENTION ..................... 800 C. POST-CHICAGO CONVENTION TRENDS ............ 802 D. THiE BERMUDA AGREEMENT ...................... 805 E. Ti ROLE OF ICAO ............................. 808 III. RECENT TRENDS .................................. 809 A. THE AI TRANSPORT COLLOQUIUM .............. 809 B. POST-COLLOQUIuM TRENDS ...................... 811 C. THE WORLD-WIDE AIR TRANSPORT CONFERENCE. 814 D. SOME INTERIM GLOBAL ISSUES ................... 816 E. OBJECTWES OF THE CONFERENCE ................ 819 F. EXAMINATION OF ISSUES -

Airline and Aircraft Movement Growth “Airports...Are a Vital Part of Ensuring That Our Nation Is Able to Be Connected to the Rest of the World...”

CHAPTER 5 AIRLINE AND AIRCRAFT MOVEMENT GROWTH “AIRPORTS...ARE A VITAL PART OF ENSURING THAT OUR NATION IS ABLE TO BE CONNECTED TO THE REST OF THE WORLD...” THE HON WARREN TRUSS, DEPUTY PRIME MINISTER 5 Airline and aircraft movement growth The volume of passenger and aircraft movements at Canberra Airport has declined since 2009/2010. In 2013/2014 Canberra Airport will handle approximately 2.833 million passengers across approximately 60,000 aircraft movements, its lowest recorded passenger volume since 2007/2008. The prospects for a future return to growth however are strong. Canberra Airport expects a restoration of volume growth in 2015/2016 and retains confidence in the future of the aviation market in Canberra, across Australia, and particularly the Asia Pacific region. Over the next 20 years passenger numbers at Canberra Airport are projected to reach 9 million passengers per annum with some 153,000 aircraft movements in 2033/2034. Canberra Airport, with its extensive infrastructure upgrades in recent years, is well positioned to meet forecast demand with only minor additional infrastructure and capitalise on growth opportunities in the regional, domestic and international aviation markets. 5.1 OVERVIEW Globally, the aviation industry has experienced enormous change over the past 15 years including deregulation of the airline sector, operational and structural changes in the post-September 11 2001 environment, oil price shocks, the collapse of airlines as a result of the global financial crisis (GFC), and the rise of new global players in the Middle East at the expense of international carriers from traditional markets. Likewise, Australia has seen enormous change in its aviation sector – the demise of Ansett, the emergence of Virgin Australia, Jetstar, and Tiger Airways, the subsequent repositioning of two out of three of these new entrant airlines and, particularly in the Canberra context, the collapse of regional airlines. -

Chapter Two: Evaluating the Economic Benefits of Connected Airline Operations

Chapter Two: Evaluating the Economic Benefits of Connected Airline Operations Dr Alexander Grous Department of Media and Communications London School of Economics and Political Science ¥ $ € £ ¥ In association with 1 SKY HIGH ECONOMICS FOREWORD 3 AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL SERVICES 39 • Surveillance • Communication EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 • Navigation o Fuel Efficiency THE CONNECTED AIRCRAFT: o Flight Inefficiency TRANSFORMING AIRLINE OPERATIONS 10 o Efficiency and Flight Stages • The Connected Aircraft Ecosystem o Efficiency and Delays • Forecast Industry Efficiencies o Separation • Next Generation Connectivity Services • Future Services CONNECTED OPERATIONS SERVICES 13 o Benefits to Safety • The Airline CONCLUSION 50 o Pre- and Post-Flight Reporting REFERENCES 51 o Fuel and Weight Optimisation Disclaimer • The Aircraft o Cybersecurity • The Airport o Arrival Prediction o Turnarounds and On-Time Departure MAINTENANCE OPERATIONS CONTROL SERVICES 18 • Maintenance, Repair and Operations o Line Maintenance o Unscheduled Maintenance o No Fault Found o Resale Value • Aircraft Health Monitoring • Data Off-Loading • Predictive Maintenance AIRLINE OPERATIONS CONTROL SERVICES 24 • Crew Connectivity o Flight Crew o Cabin Crew o Virtual Crew Room • Flight Optimisation o Live Weather o Turbulence o Turbulence and Injuries • Environmental Factors • Irregular Operations o Diversions for Medical Emergencies o Other Irregular Operations • Disruption Management o Passenger Compensation • Safety and Operations Risk • Future Regulations 2 SKY HIGH ECONOMICS Philip Balaam President Inmarsat Aviation Foreword It is my pleasure to introduce to you the second chapter of Sky High Economics: Evaluating the Economic Benefits of Connected Airline Operations. Conducted by the London School of Economics and Political Science, the Sky High Economics study is the first of its kind to comprehensively model the economic impact of inflight connectivity on the aviation industry.